On the eve of The Great War, Danish football was on top of the world. Gold medals in the pre-Olympic games 1906 were followed by silver medals at the Olympics 1908 and 1912, losing out to England in both finals. But in June 1914, the English amateur national team was comprehensively beaten in Copenhagen 3-0.

British football was the undisputed yardstick with which success and progress was measured in Danish football. After becoming popular in the 1880’s, football seemed to be losing out to other sports in the 1890’s. But then a big sports exhibition was arranged in Copenhagen in 1898, for which the amateurs of Queens Park were invited to play an exhibition match against a Copenhagen select XI. Everybody was captivated by the skills of the Scots. From that year onwards, British teams were invited to Copenhagen for a post-season tour in May or June, playing out a football festival against Copenhagen select teams.

The matches that saw the best players from the top four Copenhagen teams compete against the likes of Celtic, Liverpool, Manchester City, Newcastle and Middlesbrough attracted thousands of spectators. A new national football stadium, ‘Idrætsparken’ was built in 1911, and it was no coincidence that the opening match saw an English team, Sheffield Wednesday, play a Copenhagen select XI.

- Middlesbrough playing a Danish Select on 9th May 1907, before ’Idrætsparken’ was built Photo- The National Library of Denmark, unknown photographer

With capacity crowds of 14.000, these matches could generate revenue of up to 20.000 Danish Kroner. The annual turnover of the Danish Football Association was 1.000 Kroner at the time, so there was obviously a big economic incentive for the Football Association to groom a national team, playing similarly attractive matches.

The Danish FA agreed two international matches against Sweden in 1913, but the Danes – having developed their game through the annual matches against the British elite – were too superior for the matches to be interesting. Denmark won 10-0 and 8-0. Therefore, the English national team was invited the following year. Played in front of a capacity crowd, this match earned the Danish FA a staggering 10.000 kroner profit.

But, within less than two months, war broke out, putting an end to English teams travelling to Denmark, club teams as well as national teams. The only realistic alternative was matches against fellow Scandinavian neutral countries, Sweden and Norway. An unofficial tournament with the three national sides playing each other, home and away, was agreed, with matches to be played in June and October from 1915 onwards.

- Danish crowd for a friendly between Danish club ‘Frem’ and Swedish club ‘Göteborg’ on 21st April 1916. Photo: The National Library of Denmark, photographer Holger Damgaard

Danish club sides had been playing pre-season friendlies against Swedish teams prior to the war. In fact, in July 1914, a match between Danish team ‘B93’ and Swedish team ‘Allmänna Idrotts Klub’ had been very fiercely contested, and the Danes, thinking the referee was biased, had threatened to walk out during the match. The Swedes were furious at this lack of sportsmanship, whereas the Danes claimed that it was the way the Swedish team played that had nothing to do with sportsmanship. One of the Danish players, a student of theology, wrote an appeal in a major Danish news paper, calling for a boycott of matches against Swedish teams, until they learned to behave like gentlemen. He blaimed “the sickening national sentiment of the Swedes” for the escalation of the episode.

But now the scene was set for two international matches against the Swedes in 1915. The first one was scheduled for Sunday 6th June in Copenhagen. This turned out to be the day after the Danish King signed a revised constitution, giving women and servants the vote, as well as abolishing the privileges of the highest tax-earners in the upper chamber of the parliament. The tabloid paper Ekstra Bladet, however, wrote: “On Saturday, there were a few people talking about Denmark getting a new constitution, but yesterday, nobody gave the constitution a thought. All eyes of the nation were on the Idrætsparken field, where our stoic football giants won the international match by 2-0.”

- Crowd outside ‘Idrætsparken’ for an international match. Date unknown. Photo: The National Library of Denmark, photographer Holger Damgaard

The crowd was a respectable 11.000, only 3.000 short of the official capacity. But much to the surprise of the Danes, 2.000 of them were travelling Swedish supporters. Ekstra Bladet branded the chanting of the Swedes “a most interesting phenomenon” and a “sensation”. First they shouted out the letters “S-V-E-R-I-G-E”, and then it was rounded off in a joined “SVERIGE!” Especially in the first half, when it was still goalless, every good action by Swedish players was accompanied by this chant. In fact, it had sounded overconfident and triumphant. But in the second half, two Danish goals reduced the chant to a meeker level.

Another reporter complained that he had been prevented from taking a nap during the rather boring match, by the Swedish terrace chorus. But although the Swedes were challenging the Danes on the terraces, according to this reporter that was most certainly not the case on the field. “If you ask whether the Swedes have improved so much that there is a risk that they might beat us, a frank answer – without overdue courtesy – has to a resounding “NO””

The massive Swedish turn-up for the game, prompted the newly started sports monthly “Sports-Magasinet” to arrange a supporters’ trip for the return fixture in Stockholm on Sunday 31st October. The Danish boxing champion Dick Nelson had told about crowded special trains for sports events in the USA. Something similar ought to be feasible in Scandinavia.

- The first Danish press photographer, Holger Damgaard, did not get any photos from the match in 1915. He was sent on an assignment on an open-air theatre. In June 1916, his newspaper gave priority to the football. Photo: The National Library of Denmark, photographer Holger Damgaard

First leg of the trip was across the minefields in the Sound separating Neutral Sweden and Neutral Denmark. A steamship was chartered and set off from Copenhagen to Malmö at 8 p.m. on Saturday night. From there, a train had to be chartered to take the football fans to Stockholm. That was not easy. At first the Swedish authorities just ignored the requests from Denmark. And when the negotiations finally started, the Swedes raised the price and altered the time schedule as well along the way.

Eventually it turned out that only 8 of the 18 chartered train carriages were sprung bogies as stated in the contract. The remaining 10 were bumpy carriages, making the 11 hours ride quite unpleasant. In fact, there were delays along the way making it a 13 hours ride, cutting the duration of the stay in Stockholm down from 9 to just 7 hours. Worse, still, instead of arriving at 9 a.m., the train did not get to Stockholm till 11 a.m., by which time all restaurants and coffee shops were closed for church service.

Nevertheless, spirits were high in the carriages. Supporters had stuck small Danish flags in their hats. A choral society among the travelling fans and a supporter who had brought his violin orchestrated the singing. There was plenty of card playing, micky-taking – and a couple of photographers frequently blitzed their magnesium bombs, as they tried to document the event. But gradually, people tried to have a nap, either on the floor or in the luggage nets above the seats.

Unfortunately, there are no records of the participants. The papers named the most prominent of them, and they were from the upper middle class, heads of government offices and merchants, artisans and jewelers, journalists and artists, sport stars and aircraft pilots, or working in banks or insurance companies. One insurance company had purchased tickets for all its staff. The participants were described as “young sportsmen”, but there were also women on the trip. Some of the named business men were said to be travelling with their wives, but there were also a couple of young women travelling on their own, one of them a tennis player.

- Swedish cartoon reprinted in “Sports-Magasinet” showing the Danish football special being overtaken by a Swedish train from Norrköping enroute to the match. The farmer in the foreground says “It must be the Russians coming!”, whereas his wife just says “Holy Christ!”. “Sports-Magasinet”.

Apparently, not all the participants were football supporters. Normally a train ticket for Stockholm would cost 30 Danish Kroner. But on the football special, participants got the entire journey for only 12 kroner, so this was a cheap way of getting abroad. No wonder that the complaints abound the unruly journey were from tourists, who only saw the football special as a cheap mode of transportation.

In fact, the “Sports-Magasinet” stressed that tickets for the match were not part of the deal. It was up to the individual participants, whether they wanted a cheap standing ticket for the terraces (1 kroner) or a more expensive seating ticket in the stands (2 or 3 kroner).

When the train arrived, the tourists went off to go sightseeing, whereas the real football fans went straight to the ground to secure tickets. Rumour had it that the match was a sell-out, so they had to hurry. The frenzy for tickets convinced at least one of the young ladies, who had travelled as a tourist to go sightseeing in Stockholm, that the football was the big thing, so she abandoned the sightseeing for the football.

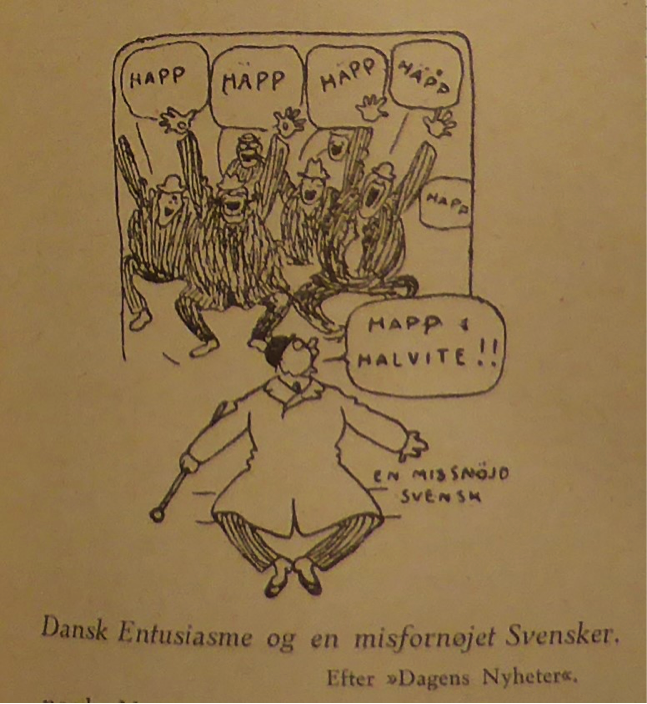

Tickets secured, the football supporters just had enough time for a visit to a swimming hall and a meal before the match, a 2 p.m. kick-off. Apparently most of the Danes went for the standing, where they launched a mock version of the Swedish chant. After the “S-V-E-R-I-G-E” they added a “H-P” – and instead of a loud “SVERIGE” they chanted “haenger paa’en” (meaning “in trouble deep”). As Denmark recorded yet another 2-0 win, it was the Danish version of the chant that rang around the ground.

- Swedish cartoon reprinted in “Sports-Magasinet” showing a Swedish spectator being unsettled by a chorus of Danish supporters 1915. “Sports-Magasinet”

Back in Copenhagen, a sort of B-international was taking place simultaneously. Players from the two top clubs ‘B93’ og’ Frem’ who had not been selected for the national team, took on the Swedish club side ‘Helsingborg’ in ‘Idrætsparken’. Telephone calls with news of the match in Stockholm were passed on to the crowd. Not just the scoring of goals. It was reported that the match was attended by the Swedish king and two princes – and that the Danish blacksmith Mr. Andersen lost his hat during the wild celebrations among the Danish fans (as well as the fact that he retrieved it later during the match). It was also reported that a Danish tobacconist was expelled from the ground for vehemently protesting an off-side decision.

After the match, there was still a couple of hours left to see the main sights of Stockholm, to have a meal and to write postcards to friends and family in Denmark about the adventure. The homeward journey was almost just as tedious as the outward one. Not only were there delays. A prepaid extra stop in Mjölby for a meal was reduced to a mere five minutes making it virtually impossible to get something to eat; preordered sandwiches were not delivered; and coffee was in short supply.

- Danish supporters watching the 1917-fixture in Copenhagen from the roof of the stand. Photo: The National Library of Denmark, photographer Holger Damgaard

The following year, football specials from Stockholm and Göteborg travelled to Copenhagen for the match in June. Newspaper estimates of the number of Swedes travelling for the match varied from 1.200 to 4.000. They were very audible and visible in Copenhagen with their Swedish flags in their buttonholes. On the football specials, they had been drinking heavily, resulting in some of them climbing out of the carriages to sit on the buffers. A few of them had been removed from the train along the way. Those who made it all the way to ‘Idrætsparken’, gathered in the corners of the ground, from where they orchestrated the singing and chanting.

Whereas the match did not attract a capacity crowd the previous year, people flocked to the ground this year. The official crowd was 20.000 – 6.000 more than the official capacity. This inevitably led to a storm of complaints that seats were sold twice over, and a lot of people on the terraces couldn’t see anything.

- Fans sneaking into ‘Idrætsparken’ around 1920. Photo: The National Library of Denmark, photographer Holger Damgaard

Within a year, the Danish-Swedish football rivalry had emerged as the most important fixture in the sporting calendar in Denmark, to a large extend fueled by the travelling football fans. From then on, the annual matches against Sweden were the biggest matches in Denmark right until the mid-seventies. By then, participation in European and World Cup Finals had become a realistic possibility, making qualifiers more attractive than friendlies.

- The crowd for the 1916 was 4.000 about the official capacity. Photo: The National Library of Denmark, photographer Holger Damgaard

Nevertheless, the newborn ‘fandom’ had its limits. Stimulated by the success of the football special to Stockholm, “Sports-Magasinet” had planned to send supporters to Norway for ski jumping and football matches. But both these sports specials had to be cancelled because of lack of participants. Maybe this made people doubt whether to trust “Sports-Magasinet”. In October 1916, only 480 people signed up for the trip to Stockholm. It took 625 participants to break-even, so this trip was rather surprisingly cancelled. Those who had signed up, were so disappointed that they set up a club, paying 1-2 kroner a month to save up for the trip in 1917. But by then the effects of German submarine-war had affected Denmark heavily, which is probably the explanation why the newspapers don’t report of travelling fans this year. Or maybe the fact that Denmark ended losing the match in Stockholm 1916 by 4-0 made it less attractive.

- Kids watching the football from nearby treetop. Photo: The National Library of Denmark, photographer Holger Damgaard

Article © Hans Henrik Appel

What a fascinating article, Hans.

As it happens I am searching for evidence of regular crowd sizes in (non-UK) European and world football up to 1920. One-off recordings of attendances for finals etc are reasonably available but I’ve not been able to find what I have for British clubs – a crowd size (estimated at times) for every match with paid entry going back to the late c19th. I am prioritising the most populous European and South American football countries and biggest stadium capacities, but Scandinavian football was obviously well organised earlier than other countries.

Have come across such attendance data in Danish football or neighbouring countries?

(I am trying to ascertain the highest average home attendances on the planet up to 1920 – it should probably be my PhD subject.)

Thanks,

Rick Glanvill, Official historian, Chelsea FC

@RickGlanvill