Missed Part 1? Please click on this link – https://goo.gl/cT3ys8

- ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE

In the nineteenth century football clubs began as member organisations in which people (members) paid an annual subscription and secured an equal vote in the club’s affairs. This was later replaced with a limited company structure in which capital is generated by the issue of shares and votes are proportionate to an individual’s shareholding. The latter constitutional structure limits the exposure of shareholders to the amount they have invested. By contrast, in a member organisation the members are jointly and severally responsible to make good any borrowings to a lender.

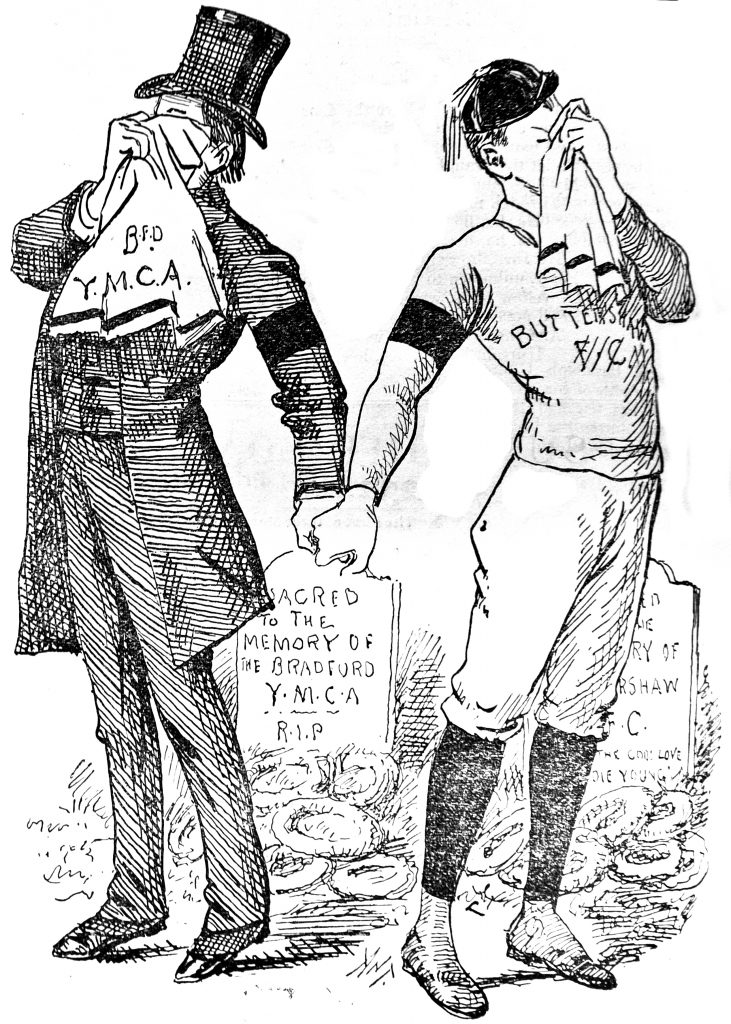

In modern times the company structure has facilitated business rescues through insolvency processes – for example the Administration procedures that have been commonplace in the UK in the last twenty years. Cultural change has also made people more amenable to insolvency action whereas maybe fifty years ago it was still regarded as an unethical form of business restructure. Historically, the risk of insolvency was a big disincentive for people to subscribe to member organisations. Faced with financial collapse, members had no wish to renew their subscriptions and be held liable for a club’s debts which meant that struggling clubs were denied the subscription revenue and the skills and experience of members who might otherwise have been able to help drive a turnaround. Little wonder then that at the end of the nineteenth century the junior rugby clubs in Bradford (like elsewhere in the north) virtually disappeared. As a consequence, member organisations were not only more vulnerable to financial failure but also less well prepared to cope with a financial crisis. Furthermore, their constitution made them inherently political organisations and because there were electoral implications arising from unpopular decisions this did not necessarily lend itself to difficult measures being enacted to remedy under-performance.

- Cartoon dated 1894 – Buttershaw Finances

- ORGANISATIONAL COMPETENCIES

The most recent experience in Bradford, where a new owner – Edin Rahic – sought to micro-manage the Bradford City football club but was found lacking in the skills and competencies to manage its affairs, is a good illustration that no business can expect to thrive without suitable leadership. Anecdotal evidence at Valley Parade and the testimonies of former staff members as well as sponsors confirm that Rahic had a negative impact, successful only in alienating and demotivating those whose support he needed.

Basic experience running a football club is obviously a pre-requisite, but so too is familiarity of managing a business. Consideration of organisational competencies is about examining the internal characteristics of sports clubs as businesses and their ability to respond to symptoms of failure.

The sort of skills generally found wanting in a situation of under-performance are both football specific as well as generic business management shortcomings, the most likely of which being inadequate financial control and direction. Football-specific issues are not necessarily the sole preserve of the team manager, although in most cases he would be responsible for player transfers or squad development. The club directors have ultimate responsibility over managerial appointments, succession planning and the longer-term interests of the club. What tends to be overlooked is the importance of stakeholder relations and networking within the football world which may be crucial to secure signings.

It has only been since the Valley Parade fire disaster in 1985 that Bradford City has been managed as a professional organisation with a complement of full-time back office staff. However, on those occasions when cash has been constrained and budgets have been prioritised towards team building, it has quite often been the case that administrative resource is sacrificed. When this is at the expense of accounting resource and restricts the ability to prepare timely and accurate trading information, it can represent a false economy as experience at Valley Parade in periods of crisis has demonstrated.

- Bradford City v Bradford Park Avenue 1968

- LEADERSHIP STYLES

It is also relevant to classify the style of leadership in a business preceding its failure. Again, this may have had a bearing on the propensity of a football club to succumb to failure as well as to respond to symptoms of under-performance. Classification comes from considering degrees of risk aversion, from cautious business managers at one extreme to adventurous risk-takers at the other. In the case of Bradford City, chairman Geoffrey Richmond was famously known for his six weeks of madness in June, 2000 when he signed star players on big contracts in a forlorn attempt to preserve the club’s Premier League status. An equally dramatic gamble was made by the Bradford Park Avenue chairman, Harry Briggs in 1907 when he championed abandoning rugby – the so-called Great Betrayal – despite not having yet secured membership of an association league competition. Richmond was not as fortunate as Briggs in escaping financial failure, but it helped that the latter had the funds to underwrite his venture.

Another form of assessment is the extent to which different regimes were attuned to commercial opportunity, not simply with regards to taking a gamble through a major signing or investment in stadia facilities, but with regards to optimising income through sponsorship or commercial activity and being attuned to profit. The traditional approach in Bradford through to the mid-1960s (when the charismatic Stafford Heginbotham became chairman at Valley Parade) was that club directors served in a stewardship capacity to safeguard City or Avenue as local institutions. Ambition was then limited to preventing failure, rather than achieving success and striving for advancement.

Reluctance to take risks can contribute to business failure in the same way that innovation or radical change may result in a club becoming financially over-committed. We might also consider the relative influence of the team manager in relation to his chairman. To what extent does a dominant chairman dictate team selection against the better knowledge of the manager (examples of which are not confined to Bradford)?

- Bradford Park Avenue v Bradford City 1967

- THE DEMISE CURVE

Irrespective of market sector, an under-performing business generally passes through the same phases in the period immediately preceding its collapse. The sequence is generally referred to as a demise curve, the latter stages of which tend to involve a sequence of financial crises and an acceleration in the symptoms of distress.

What happened to Bradford Park Avenue in the eight years before liquidation in 1974 provides a good illustration of this. In its last four seasons as members of the Football League, the club finished second to last and then bottom on three occasions before failing to secure re-election in 1970. Prior to liquidation in 1974 it then spent four seasons as members of the Northern Premier League, struggling to remain solvent. After mounting debts forced the club to vacate Park Avenue in 1973 it spent a final season sharing at Valley Parade.

The initial symptoms of distress were confined to trading losses and headlines about indebtedness, but after 1968 there were frequent cash crises and appeals for financial assistance. Those in charge responded to problems with increasingly desperate, panic measures that failed to remedy the club’s status. As a consequence it entered a vicious cycle, a downward vortex characterised by organisational implosion and a permanent state of emergency measures. In its final year in the League the club was run by an eccentric chairman, Herbert Metcalfe but by then its fate was sealed and the club had passed the point at which it had lost credibility with its fans, other football stakeholders and its creditors. Between 1970-74 it existed in a zombie like state, unable to kick start a revival to regain League membership.

There are tell-tale signings of mounting financial problems that most football followers will recognise. The selling of players, loss of key employees and the imposition of economy measures are prime examples. In the 1980s it was common practice for clubs to sell their freehold property assets to raise money. Board room squabbles are another clue, invariably focused on money issues and the willingness or otherwise of directors to guarantee debts or inject new funds. There are other more mundane examples and one such historic indicator of financial health has been the state of a club’s match-day programme. In Bradford there have been various examples of lower quality programmes having been introduced by City and Park Avenue to save money. This was particularly notable in 1964 (and again in 1983) at Valley Parade where programmes were printed on cheap paper and even staples were dispensed with.

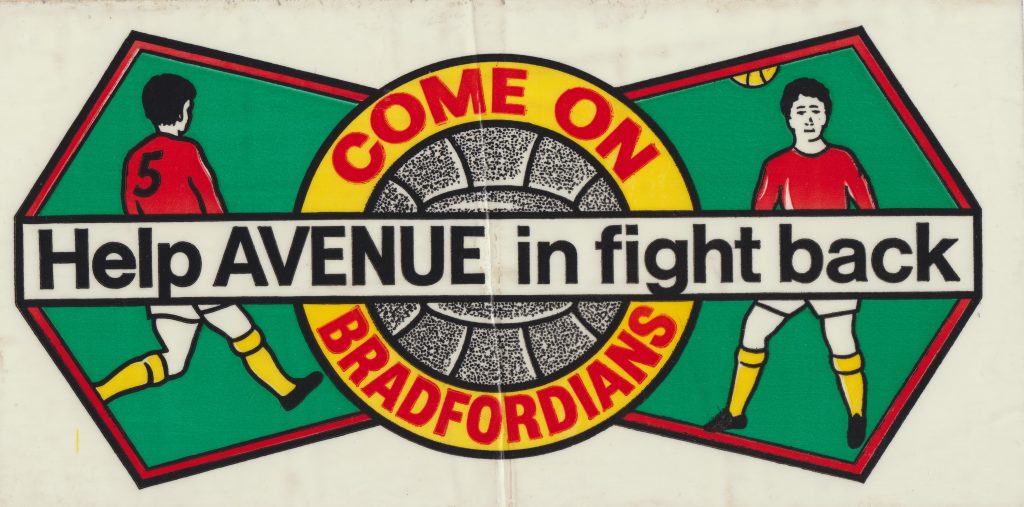

- Bradford Park Avenue bumper sticker 1972

Football clubs seemingly have more lives than a cat and even the bleakest financial failures are averted by last minute rescue (Bradford Park Avenue aside). However, recovery may be more apparent than real and at Valley Parade it took the best part of ten years to recover from a second formal insolvency process in as many years in 2004. The club was weighed down by obligations to repay its creditors that sapped much of its vitality and the self-confidence of its leadership. A football club can never truly escape the legacy of being a struggler and although Bradford City now has the city to itself (with the reformed Bradford Park Avenue attracting minimal crowds in the sixth tier of English football) it remains trapped at a level out of proportion with the size of Bradford’s population. However at least the club has survived.

Article © John Dewhirst

This is a brilliant article by John Dewhirst. What should have been clear by at the very latest the end of the 1950’s was that the only sensible solution to two ailing clubs in a city that could never be described as sports-mad was to merge. But typical Yorkshire tunnel vision allied to native obstinacy and pigheadedness prevented it. From his article I see that a Mr. H.B.Metcalfe was shown in a programme as a City director. I had always associated him solely with Avenue. Maybe it was another with the same name.