On Sunday the 10th of March 1912, 13.000 football enthusiasts saw Belgium’s national team lose to the Netherlands one goal by two in Antwerp. The so-called ‘derby of the Low Countries’ had established a venerable history by then. In April 1905, the two national teams had played their first official fixture in Antwerp. Soon, they would square off semi-annually in Antwerp or in Dutch towns like Rotterdam. The derby attested to the growth of football in both countries since the foundation of the Dutch (1889) and Belgian (1895) football associations.

- A snapshot of the ‘real’ Low Countries derby of 1912. Dutch goalkeeper Göbel stops a Belgian attempt on goal (Revue der Sporten)

But it is not the early years of football by the North Sea which are of interest here, nor is it the Low Countries derby. Hours before the derby’s March 1912 edition, another match was played in which an eleven composed of Belgian sports journalists confronted a team of their Dutch peers on the grounds of the Antwerp Football Club. Again, the Belgian side was the lesser of its Dutch rivals and suffered a crushing 4-0 defeat. Despite this disappointing result for the Belgian team, they confronted their Dutch colleagues again in Antwerp one year later, prior to a new edition of the actual Low Countries derby. This time, it was the Belgians’ turn to triumph as they beat the Dutch pressmen 3 goals to 1. At first glance, these games seem to be of only novelty value, a bit of sporting fun for journalists before they reported on the real derby. Their importance, however, goes beyond the trivial. In a period in which Belgian and Dutch sporting cultures were expanding, these footy friendlies symbolised the expansive growth of a key component of this culture, the sports press.

- Here, French reporters take on a squad of the Daily Mail in Paris in 1908 (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, France)

- The phenomenon of friendly matches between sports journalists was not limited to the Low Countries. (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, France)

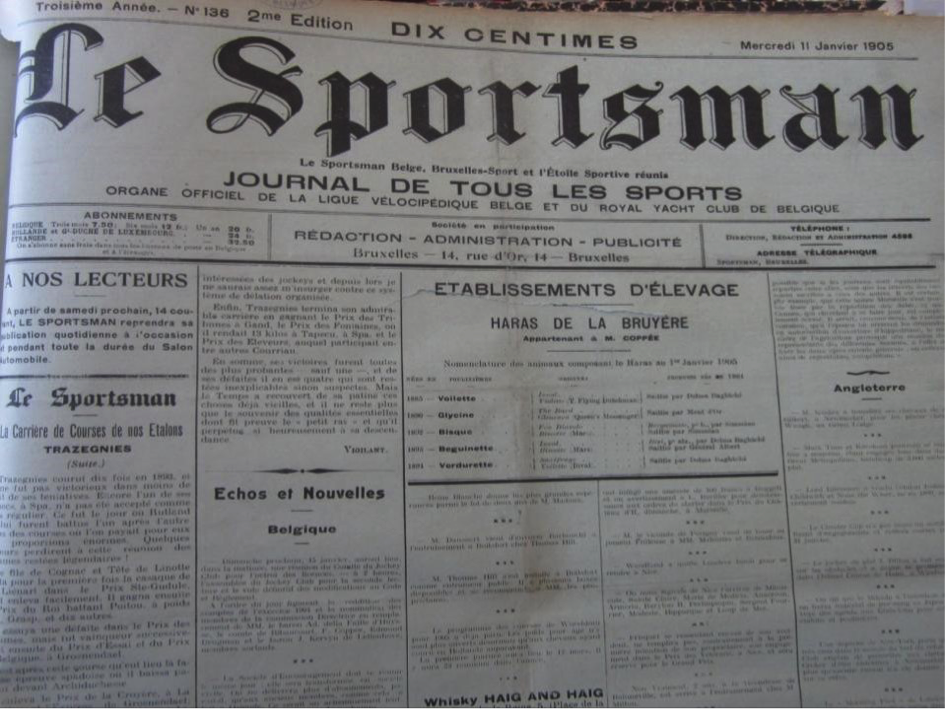

Belgium, the press had kept pace with the growth of sports since the 1890s, when sports increasingly became part of mainstream leisure culture, thanks to the spectacular popularisation of cycling. With the cycling paper Le Véloce in 1893, Belgium got its first sporting daily. Within a few years, another daily sports paper, Le Rush, joined it. But not only specialist publications now featured sports news. From 1891 on, general dailies like Brussels’ La Chronique began to pay attention to sports, hoping to attract more readers in a period which saw a massive expansion of the press as a whole and in which competition between titles was rife. After 1900, press attention for sports news gradually grew as football, cycling, or new phenomena like motor sports kept gaining in popularity. Milestones included new titles such as Le Sportsman (1904) or Le Vélo (1908), but also the enthusiastic adoption of sports news by the new daily La Dernière Heure in 1906, the first Belgian paper modelled after the sensationalist British tabloids. Although they ranged from a few lines to the better half of a page, on the eve of the Great War no paper could go without its sports section.

- The front page of Le Véloce (1893)

- The front page of Le Sportsman (1904)

- The front page of Vélo-Sport (1908)

This growth of the sports press was a precondition for the football matches between Belgian and Dutch journalists to take place. As papers increasingly needed reporters supplying them with copy of sports news, specialised sports writers became part of the press landscape. The Belgian selection for the 1912 match gives a good image of this growing cohort. Its makeup was evenly divided between representatives of general dailies, such as S. Davignon of the Catholic Le Vingtième Siècle, Albert Mestdagh of Le Patriote and Emile Kneipe of La Dernière Heure, and reporters for the specialist sports press like Caro, Leroy and Edouard Hermès, all of Vélo-Sport. The Dutch team showed a similar dynamic, with journalists from general dailies like Jongnière of the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant donning the same characteristic orange jersey as writers for sports weeklies like Frenkel and De Vries, who wrote for De Sport.

Not all of these men were full-time sports journalists. Several of those in the Belgian team combined their sports writing with reporting on other news, or with other occupations. Some still had an active sporting career. Graindorge and Caro, who made up the defence of the Belgian press team of 1913, also played for First Division clubs F.C. Liège and Club Sportif Verviétois respectively. In the same team, Danly of the weekly Echo-Sportif played hockey and practised athletics for the Racing Club Bruxellois. Indeed, active or former sportsmen were especially valued as sports journalists for their first-hand experience of what they reported on. With W.J.H. ‘Pim’ Mulier, the Dutch team of 1912 and 1913 even featured one of the Netherlands’ most prolific sportsmen. Mulier had been active in a range of sports since the late 1870s as an athlete, administrator and journalist for Het Sportblad. Many even considered him the father of Dutch football. At 47, he was the oldest but also most famous man on the pitch.

- Pioneer on the pitch. In 1912 and 1913, Pim Mulier – considered by some to be the ‘father’ of Dutch football – joined the Dutch journalists’ team (Revue der Sporten, 1912)

The Belgo-Dutch football friendlies not only symbolised the growing number of sports journalists, they also attested to their increasing identification as members of a distinct occupation. Modern sports constituted an industry as much as a culture and gave rise to new, sports-related occupations, from professional athletes to producers of commodities like footballs and tennis rackets. As sports media were a cornerstone of this industry, reporting on and promoting all things sports, the sports journalist was one of these new sports-related occupation par excellence. With sports journalism coming of age in Belgium, its practitioners showed a growing interest in associating with each other in order to socialize but, also, to share experiences and discuss professional problems. Playing a friendly game of football against colleagues from across the border offered an ideal occasion for this.

Indeed, football games featuring teams of sports journalists had been played earlier already. In May 1911, a side of sports chroniclers had competed with squads of veteran players of Belgian top teams Daring Club Brussels and Club Bruges. As the journalists’ team contained several of those who took part in the first journalists’ derby one year later, it is not unlikely that the idea for the event was first put forward here. In the case of all these matches, what happened off the pitch was as important as what took place on it. The game itself was always followed by a dinner, speeches and merry-making, further tightening the bonds between journalists. As a report on the first journalists’ derby of 1912 shows, their atmosphere was one of boyish fun, including cheerful improvisation in a last-minute quest for a referee and the presence of enthusiastic fellow pressmen in the stands.

What might be the Belgian journalists’ team. While the photograph was not accompanied by a description, the sign in the back clearly indicates that this is the Antwerp F.C. pitch. In addition, the presence of some older figures in the team suggests that this was not a regular side (State Archives, Brussels, Belgium)

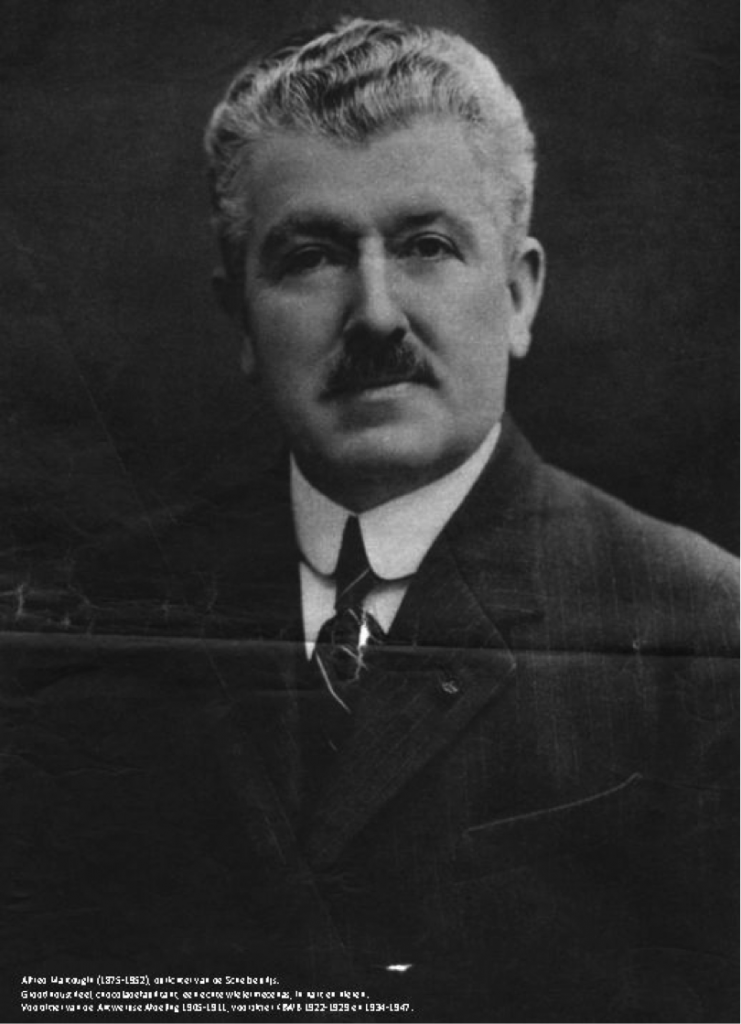

Further attesting to the journalists’ derby’s importance as a site for socializing and networking between sports writers was the fact that, in Belgium, the derby was closely linked to the latter’s increasingly active professional associations. In 1896 already, the ‘Syndicate of the Cycling Press of Antwerp’ had been established by leading figures in the city’s cycling press. Broadening its scope in 1901 to include journalists of all sports, the Syndicate provided a place for socializing but also acted for its members in addressing professional issues such as press access to sports events. Within this context, it took the initiative to organise the first edition of the journalists’ derby in 1912. The following year, its treasurer and former president Alfred Martougin, a successful businessman, administrator in the Belgian Cycling Union and sports journalist for the socialist daily Le Peuple, donated a trophy carrying his name to the derby which would go to the winner of each edition.

Alfred Martougin: businessman, sports administrator, journalist and donor of the Coupe Martougin.

However, the expansive growth of sporting culture in the years just prior to the Great War ensured that the Antwerp Syndicate was no longer sports journalism’s only professional association. In Liège, the ‘Association des Journalistes Sportifs Liègeois’ was formed around 1911. Amongst other things, it set up a central collection point for the results of sports events, making it easier for its members to get the information they needed. On the 30th of May 1913, moreover, the first national association of sports journalists was established in the form of the ‘Association Professionelle Belge des Journalistes Sportifs’. Albert Mestdagh of Le Vingtième Siècle, a regular in the journalists’ derby Belgian team, became its first treasurer.

The journalists’ football derby, then, was more than a bit of fun. It showed a sporting occupation in full expansion, in line with the unceasing growth of sports culture. The final pre-war edition of the game was played in Antwerp on the 15th of March 1914, the Belgian side winning by 2 goals to 1. According to the rules of the Coupe Martougin, this second consecutive victory (after their 3-1 win in 1913) allowed them to take home the trophy once and for all. A few months later, the Great War broke out. While the Netherlands remained neutral, Belgium went through four years of harsh German occupation. After the Armistice, however, the journalists’ derby was given new life. On the 5th of September 1920, during the last days of the Summer Olympics in the city, Antwerp again hosted a match Belgian and Dutch sports journalists, the latter beating their southern neighbours one goal to nil. The derby’s revival was aptly symbolic. Over the course of the 1920s, the sports press in both Belgium and the Netherlands would witness new, unprecedented growth. With it, sports journalism’s development as a distinct occupation with its own rules, customs and professional culture would blossom as well.

Article © Stijn Knuts

![“And then we were Boycotted”<br>New Discoveries about the Birth of Women’s Football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 11](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Boycotted-Marco-Part-11-440x264.jpg)