The first experimental match without the offside rule was played over 50 years ago.

The debate about the offside law in football has been given a new lease of life thanks in part to Marco van Basten. It has resulted in a number of matches trialling the absence of offside, just to see what would happen. Yet they are just the grandchildren of an experimental match played well over 60 years ago.

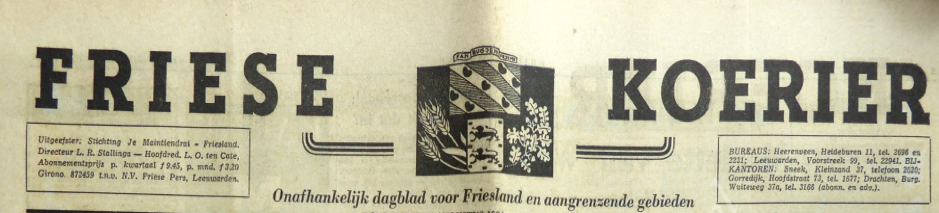

In 1956 Belgrade rivals Partizan and Crvena Zvezda played a match in which no offside was applied. In fact, the organisers went beyond that, as an article in the Dutch newspaper De Friese Koerier of 3rd December 1956 confirmed: “The throw-in had been replaced by a kick-in, and corner kicks were taken from the place where the ball had crossed the goal line, except if that was in the penalty area.”

- De Friese Koerier

The match was officiated by two referees, assisted by two linesmen and a timekeeper. Plenty of goals were scored: 7-4. “The fans went home most contented.”

An interesting case evidently, not only owing to the absence of the offside law, but also to the number of referees and the throw-in being replaced by the kick-in or an indirect free kick.

The Netherlands

The Netherlands has been active on this front as well. In January 1965, Feyenoord Rotterdam submitted a request to the Dutch national football association KNVB, asking to be allowed a number of innovations in a friendly with Alkmaar, one such innovation involving limiting offside to an area eighteen yards from the opponent’s goal line. This idea had garnered a great deal of attention in the Dutch press, and Feyenoord wanted to test it in practice.

- Feyenoord Rotterdam badge

In a response, FIFA denied there were any plans to introduce new laws, dismissing the idea as a rumour. FIFA ordered the KNVB not to grant Feyenoord permission to play a match trialling the proposed offside amendment. Lo and behold, the request was denied.

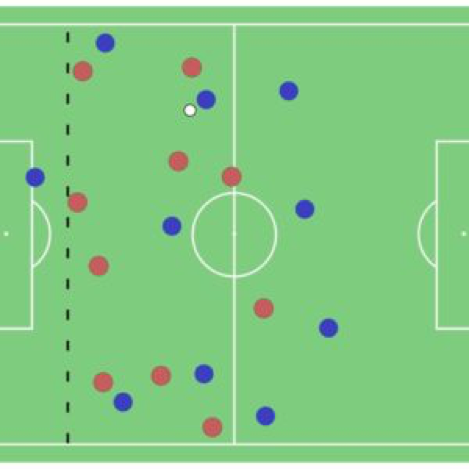

Three years later, however, the idea was rekindled at the initiative of television current affairs programme Brandpunt. On 25th January 1968 Ajax and AZ ’67 played a match without offside. In addition, the throw-in had been replaced by an indirect free kick, taken from the spot where the ball had left the field of play. Apart from a few dozen people involved in the organisation, spectators were not allowed to watch the tie, which was played in two halves of 30 minutes each.

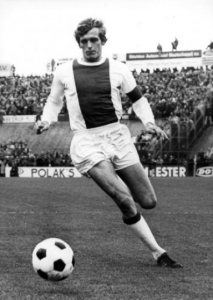

During the match, centre forward Johan Cruyff and winger Piet Keizer were reduced to goal-hanging, mostly in vain. “Most of the time he was of little use,” the reporter for the Het Vrije Volk newspaper said of Cruyff. Which, De Telegraaf newspaper reported, could hardly be blamed on Cruyff, for neither he nor Keizer was involved in play much by their teammates. Only Vasovic, Ajax’ sweeper, made good use of the situation by regularly playing long balls that totally confounded the AZ ’67 defenders.

- Johan Cruyff

- Piet Keizer

De Telegraaf rather liked the new rules, commenting that there was much more space on the field and play was not as tight. “This makes sense, for when a forward keeps hanging near the other team’s goal, irrespective of where the ball is, a defender should be close to guard him. This stretches the field of play, so to speak.”

Scrapping the throw-in also delighted the newspaper: “It speeds up play and a kick-in (free kick) near the goal line can, in many cases, pose as much threat as a corner kick.” The only disappointment was the number of goals scored. Twelve years earlier in Belgrade, there had been 11 goals. This time round, Ajax managed to beat AZ ’67 by 2-1 only.

All the same, De Telegraaf did not expect the match to have any consequence: “It is rather unlikely that the international football authorities up there will be tempted to introduce these changes in the near future.” Nearly fifty years on we cannot but agree.

Article © Jurryt van de Vooren

Translated from the original Dutch by Ben van Maaren

See sportgeschiedenis.nl – published on Playing Pasts by kind permission of the author.