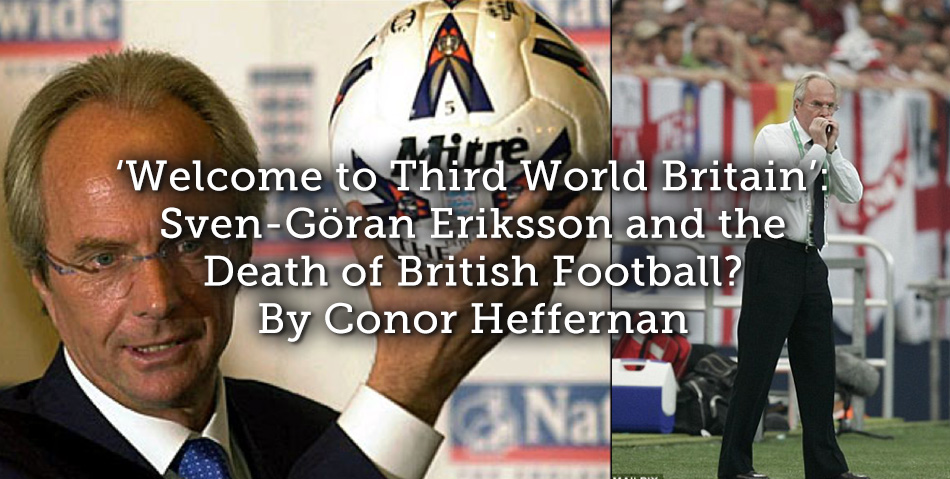

- Sven-Göran Eriksson

Intro:

One of the favoured and oftquoted lines from English historian Eric Hobsbawm is that ‘the imagined community of millions seems more real as a team of eleven named people.’ Aside from encouraging a generation of sporting historians to continue their endeavours, this quote has particular salience when it comes to issues of nationhood, identity and unfortunately, exclusion.

Building on Hobsbawm’s somewhat curt observation, the following post details a seminal moment in the history of English football. That is, the appointment of Sven-Göran Eriksson as England’s first foreign football manager in 2001. Coming at a time of increasingly destabilised English identity, Eriksson became a vilified figure amongst portions of England’s press and indeed its fan base. Seen as emblematic of a wider problem of globalization, the Swedish manager sparked a nationwide discussion about the importance of English identity.

Through an examination of several key media outlets, the post highlights some of the more salient discussions surrounding the Swede’s appointment and how they related to a wider national uncertainty about what it meant to be English at the dawn of a new millennium.

The Times They Are a Changing

Sven’s appointment did not of course occur within a societal vacuum. As detailed by several scholars of both globalization and sport such as Ben Wellings, Timothy Garton Ash and Martin Cloonan, the late 1980s and 1990s were decades of remarkable change within the British societal spectrum. Multiculturalism was growing, Great Britain was turning more towards its European allies and seeming total EU integration seemed all to likely. Compounding this were discussions on Irish, Scottish and even at times, Welsh devolution. England as detailed by Kipling et al. seemed to be a distant memory. Harold MacMillan’s winds of change had become something of a tornado.

Within the realm of football, such changes began to manifest quite significantly within both British fan culture and the actions of the English media. Regarding the former, John Gerland and Mike Rowe have noted the increasing jingoistic behaviour amongst both hooligans and the regular hoi polloi attending English matches. This was highlighted with reference to the increasing importance of the St. George Cross in public and a more serious matter of xenophobic attacks on opposition fans. The latter was seen most publically during the 1996 European championships which saw a large-scale riot take place in London’s Trafalgar Square following England’s defeat to Germany in the semi-finals. Such assaults were not confined to England’s capital either as one Russian youth was stabbed in Brighton that same night after his attackers supposedly mistook him for a German supporter.

- Trafalgar Square Riots During the 1996 European Championship

Rather than attribute the blame solely on the English fans, the 1996 incidents were notable owing to the public shaming of certain media outlets. Most famously this occurred when Jack Straw, the Labour Party’s Home Affairs spokesman, vehemently argued that

Last night’s scenes [the riot in London] will serve to force some elements of the tabloid press to reflect upon the irresponsible attitude they showed in advance of last night’s game.

Similarly, the all- party National Heritage Committee argued that

The xenophobic, chauvinistic and jingoistic gutter journalism perpetrated by those newspapers…may well have had its effect in stimulating the deplorable riots following the Germany victory in the semi-final.

Also of note regarding the media, was the increasing concern amongst certain journalists about the influx of the foreign footballer. A trend many journalists feared was destabilising or indeed diminishing the value of the English born athlete. Such conversations reached a fever pitch in 1999 when then Chelsea Manager Gianluca Vialli fielded a starting XI without a single British player. Much was made of the fact that this was the first time in one hundred and eleven years of English football, marking some 150,000 fixtures that such a feat had arisen. Further compounding fears was the high probability that further teams would emulate Vialli’s non-partisan selections. Indeed, such conversations remerged with a vengeance in 2005 when Arsène Wenger fielded a match day squad entirely devoid of British born players.

- Gianluca Vialli and his all-foreign Chelsea XI

A Changing Tide

On the field for the national side, matters were not much better. While England had surpassed expectations by reaching the semi-finals of the 1996 European Championships, the years following the tournament were characterised by managerial gaffs surrounding pre-destination, David Beckham’s ill discipline at the 1998 World Cup in France, a poor showing in the European Championships in 2000 and the fear that England would miss out on qualification for the 2002 World Cup. Confidence in the English national team seemed to reach an all time low when Eriksson’s predecessor Kevin Keegan tendered his resignation in a bathroom stall at Wembley in the wake of a 1-0 defeat to Germany during the World Cup qualification process.

- Kevin Keegan’s Final Game as England Manager

With Peter Taylor appointed as interim manager, English fans, the media and FA officials began discussing Keegan’s replacement. A series of events that would soon would see English managers discouraged, foreign managers touted and sections of the English media descend into a nationalistic fury.

Public Soul Searching

In the immediate aftermath of Keegan’s resignation the general consensus was that an English manager would be appointed in the coming days. So confident in this eventuality did the bookmakers become that the top picks boasted Terry Venables, Peter Taylor, Alan Curbishley and a series of other Anglo-Saxon names. The wildcard of the bunch being Arsène Wenger, the Arsenal manager known to England fans for nearly a decade. In short, it seemed that the next England manager would be well known and familiar to all. Few expected the Football Association to venture further afield.

In FA Headquarters however, it quickly became apparent that the managers being discussed in the media were inexperienced, undesirable or unobtainable. Soon feelers were put out to managers further afield, one being Sven-Göran Eriksson. Speaking to FourFourTwo nearly a decade after his eventual England appointment, Sven recalled his initial incredulity at the prospect. In fact, the Swede supposedly told his agent that ‘no foreigner could take England.’ A statement Eriksson soon disavowed. Within two days he expressed his interest and in the coming months his appointment was made. A decision that caused considerable chagrin amongst certain English journalists and persona.

Regarding the criticisms surrounding Sven’s appointment, it is useful to break the attacks in two; the first revolving around a supposed diminishing status of English prestige and the second concerning fears of European encroachment in British life.

Regarding the former, The Sun newspaper declared the appointment, ‘a climbdown…a terrible, pathetic, self-inflicted indictment.’ Though one may be forgiven for expecting such jingoism from the tabloid press, the sentiment was found elsewhere in the footballing world. Jack Charlton, the Englishman famed for his exploits as manager of the Republic of Ireland was quoted with little irony as saying that hiring a foreigner was a ‘recipe for disaster.’ Similarly Gordon Taylor, then chief executive of the Professional Footballers Association, labeled the appointment as ‘a betrayal of our heritage . . . [which] sends out the wrong signals.’

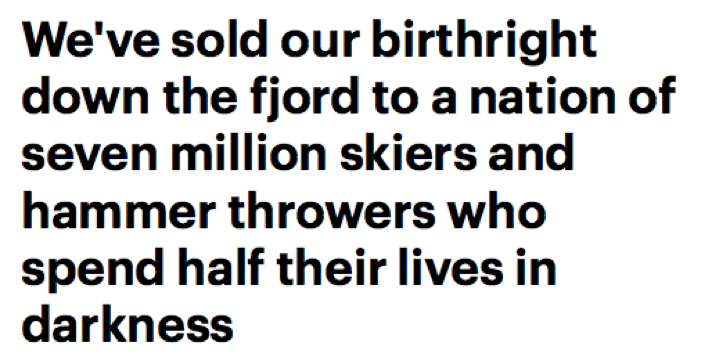

- Jeff Powell, ‘We’ve Sold Our Birthright Down the Fjord to a Nation of Seven Million Skiers’, The Daily Mail, 1 November (2000)

Even more worrying for some was what Sven’s appointment represented for British life in general. Jeff Powell of the Daily Mail lamented that ‘We’ve sold our birthright down the fjord to a nation of seven million skiers and hammer throwers who spend half their lives in darkness.’ Britain he asserted, was now ‘a Third World Country’. Seeking a more humorous approach to the matter, Bruce Barnard claimed that England how well and truly been invaded by Sweden following the emergence of Volvo, Ikea and now Sven into the country. Seeking to protect his underlings, John Barnwell, then head of the League Managers’ Association, argued that

The appointment of a foreign coach beggars belief. The England manager is the figurehead of our game because it’s the pinnacle job in this country, and this is another example [italics added] of us giving away another of our family treasures to Europe.

Such discourses were not limited to the media as Sven’s first few weeks in England would see the Swede followed by Ray Egan, a retired police officer known publically for dressing up as John Bull. For Sven, Egan carried a placard proclaiming that the English should hang their heads in shame for hiring a foreigner. Clearly the English football team was more than just a starting XI.

Importantly even neutral or positive comments on Sven’s appointment highlighted his outsider status. In a communiqué published in April 2001, the FA made great use out of the fact that Sven was England’s first foreign manager. David Bond in the London Evening Standard argued that the new Swedish manager had brought new and exotic techniques with him to the country, most notably a Sports Therapist. The BBC even ran a story of Sven piece whereby readers could learn how the mysterious foreigner had found his way to England. In short, media discussions both in favour and against Sven’s appointment were either predicated on, or included his foreign status.

The Lasting Legacy

- Sven at the 2006 World Cup

Though the above media discourses may appear to have been a flash in the pan, a knee jerk reaction to a seismic change in a notoriously conservative sport, this was not the case. If anything the reaction continued as England underperformed at major tournaments in the eyes of the public and the media. In a fascinating piece of work, Vincent et al. (2010) examined media discourses surrounding England’s performance at the 2006 World Cup in Germany. Their key findings support many of the claims made above, namely that

The narratives seemed designed to galvanize support for the English team through references to historic English military victories and speeches. These served to rekindle images of bygone, mythical, and imperialistic eras. The newspapers also reverted to an ‘us vs. them’ invective in blaming Swedish manager, Sven-Göran Eriksson, for England’s failure to win the tournament with the ‘greatest generation’.

This ‘us vs. them’ mentality arguably continued through the reign of Fabio Capello’s tenure as England manager from 2007 to 2012 which saw the Italian criticised at times for his lack of ‘Englishness’. Indeed a 2010 Daily Mail article on the then England manager asked a series of football journalists if ‘the post should always be filled by an Englishman?’ The almost unanimous yes answer indicated that little had changed.

Article © Conor Heffernan