NB – This article was first published on Playing Pasts in 2017

The Boat Races are a contest not only of brawn but also of brain. Alongside the eight athletes in the boat sits the cox: responsible for steering, managing and motivating the crew from Putney to Mortlake. The intricacies of this particular course – its stream, tides, and bends – show clearly how much of a decisive role coxing can play in a race. This year’s open weight Boat Races saw Matthew Holland in the cox’s seat for the Cambridge women’s Blue Boat, and Victoria Warner for Isis, the Oxford men’s reserve crew. Both illustrate the unique position of the cox as being able to race in men’s or women’s crews according to their own preference, or the opportunities available to them, rather than being determined by their own gender – except in international racing, where under FISA rules the same criteria apply to coxes and athletes.

This is not a new phenomenon, although in the context of Boat Race history, a relatively recent one: the first time the men’s Boat Race was coxed by a woman was in 1981, with Sue Brown for Oxford. In 1985, the Cambridge men had their first female cox in Henrietta ‘Henry’ Shaw, and in 1989, both men’s Blue Boats were coxed by women, with Alison Norrish for Oxford and Leigh Weiss for Cambridge.

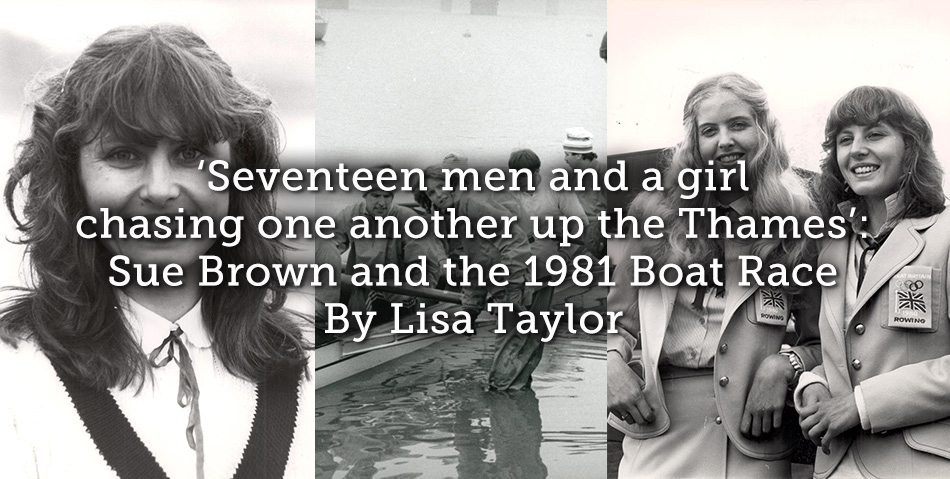

- Sue Brown c. 1982 – Copyright John Shore (River & Rowing Museum Collection)

- ‘Henry’ Shaw with her Cambridge Crew in 1985 – Copyright River & Rowing Museum

It should be noted that men also have a history of coxing women’s crews – the 1984 Cambridge women’s Blue Boat is one such example. (Records of the women’s crews are less comprehensive than for the men’s with CUWBC providing details back to 1980, and OUWBC to 2009 – 1984 therefore might not be the first such example, but illustrates the fact that coxes have moved both ways between men’s and women’s squads for some time.) There was precedent for this in the Oxbridge community: at Somerville College in Oxford, for example, the use of a male cox and male coach to act as chaperones to female crews had been an explicit condition of being permitted to go out on the water from 1884. The control offered by the cox’s seat had historically been allocated to men to legitimise pursuit of the sport by women. Yet women coxing men was seen to be more problematic, precisely for this reason of control, especially in the historic (and, historically conservative) Boat Race.

Sue Brown came to her Oxford crew with Olympic colours, having coxed the women’s four at Moscow 1980, and had previously coxed in the Women’s Boat Race, yet her selection for the Boat Race would still ruffle feathers, and generated significant media attention. She was, however, ‘a nightmare for the reporters because she had little to say to their repetitive trite questions about women’s lib, making history, had she got a boyfriend in the crew, and so on’ (Christopher Dodd, The Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race, 1983: 138). She was not explicitly taking a stand on the issue of gender, but pursuing new challenges within her sport.

- 1980 Moscow Olympics- Sue Brown (right) with squad-mate Jo Toch (left) Copyright River & Rowing Museum

David Hunn of The Observer described Brown as ‘a composed little waif’ (5 April 1981: 23). Dodd remarks on how ‘without resorting to the gimmickry of showing her legs or wearing tight singlets, she looked like a revelation in every picture taken’ (1983: 138), and, lifting language from former Cambridge cox Robert Swartwout, notes the ‘taper waist and fair complexion’ of Henry Shaw in a report for The Guardian (6 April 1985: 13). Factual commentary on weight is not unusual when reporting on the Boat Race or other competitive rowing events, since the relative weights of crews often used to assess their likely prospects against one another. Yet here, the physical characteristics of these women appear to be highlighted to reiterate their femininity while holding a commanding role over a crew of eight male athletes.

Oxford’s 1981 performance resulted in a decisive victory of eight lengths, leading Hunn to report that Brown ‘would be in line for Woman of the Year but for the amorous activities of His Royal Highness’ (Prince Charles, whose engagement to Lady Diana Spencer had been announced just a few weeks previously). Her selection had profile, and in this competitive community the fact that her race was so successful would undoubtedly have helped legitimise the idea of female coxes in the men’s races. She was not, however, treated to the ‘ritual ducking’ that ordinarily follows a win (Hunn, 1981: 23). Neither was she invited to join the Leander Rowing Club – a privilege of Boat Race winners – since they did not admit women, and would not do so until 1998.

Article © Lisa Taylor

![“And then we were Boycotted”<br>New Discoveries about the Birth of Women’s Football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 10](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Boycotted-Part-10-Marco-Giani-440x264.jpg)