Introduction

In 1907, and again in 1931, Dwight Filley Davis made a number of claims relating to his significant role in fostering international tennis matches, and the inception of the challenge match that bears his name. Recent research published in the Journal of Sport History has challenged Davis’s assertions. In the first part of this article, published on 29th October, we highlighted how international challenge matches pre-dated the inception of the Davis Cup by nearly 20 years, and that during this period international matches were regularly played between England and Ireland. In addition, we highlighted that Americans, such as Dr. James Dwight and Henry Ditson made several attempts to entice the British ‘cracks’ to American shores in the late nineteenth century, with varying degrees of success.

In the second part of this article, for part one please see – https://goo.gl/4jCvWA, we seek to provide evidence that further disputes Davis’s claims. In particular, we will address how the leading players, on both sides of the Atlantic, collaborated to develop the critical relationships necessary for development of Anglo-America competition.

The Emergence of the American Challenge

The early lawn tennis international matches between Ireland and England, played from 1881 onwards for over a decade, were of considerable interest, and it was only in the mid-1890s when the leading American players advanced to such a degree that the British began to take notice. It was not until 1894 that a highly-ranked British player, Manliffe Goodbody, crossed the Atlantic to compete on American shores. His stay culminated in a loss in the Challenge Round of the US National Championships (forerunner of the U.S. Open) to Bob Wrenn, whereupon The New York Times reported: ‘Goodbody deserves a vote of thanks, according to lovers of tennis. His appearance at Newport imparted a kind of international flavor to the proceedings’ and proclaimed his ventures would ‘lead to international contests’ being staged ‘on both sides of the water’’. The editor of Golf and Lawn Tennis (G<) proffered that Goodbody had proposed the idea of an ‘international competition between say six of the leading players of each country, on a perfectly neutral soil, and under neutral conditions’.

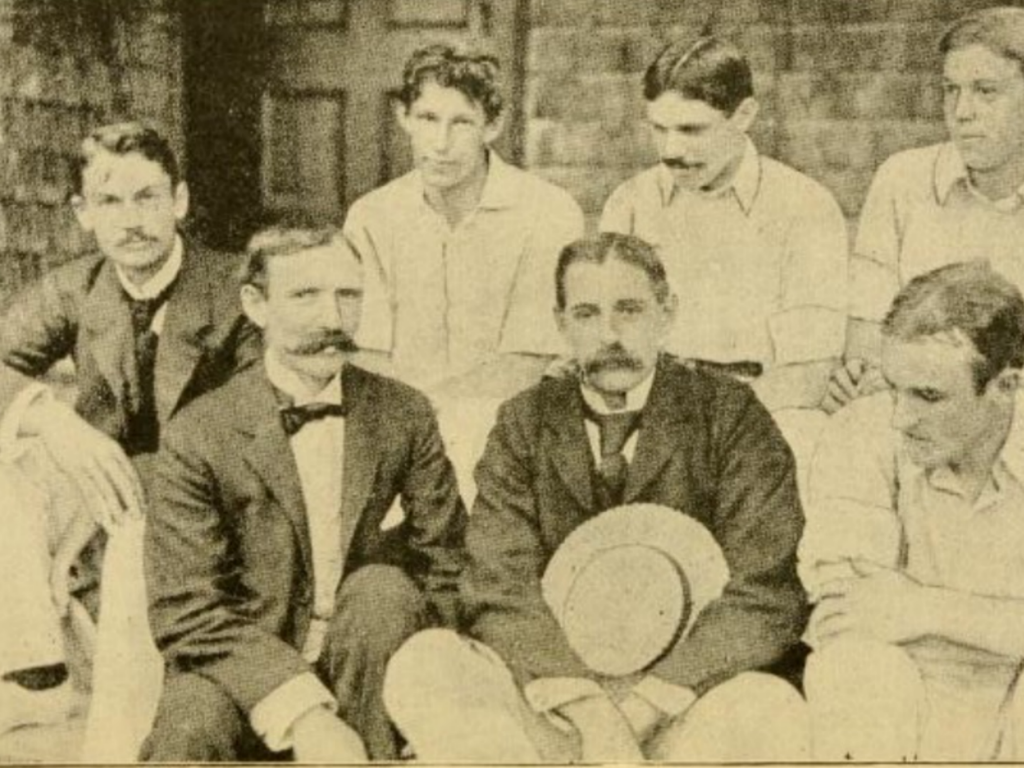

On leaving America, Goodbody promised to extend invitations to other top British/Irish players for the following year. Irishman Joshua Pim, who was the two-time and reigning Wimbledon singles champion, duly took up the offer and ventured west with his compatriot Harold Mahony.

- Harold Segerson Mahony (back, left) sitting next to Bill Larned in 1895. Dr Joshua Pim is seated in the middle of the front row.

Both performed well against top American talent and after meeting with Dwight, it was agreed that Americans would venture east to compete in British tournaments the following summer. Ultimately, only one American, Boston’s Bill Larned, travelled, but he and Mahony struck up a friendship as they travelled together over a two-month period – including a sojourn to watch the annual England-versus-Ireland match – to compete in six British tournaments. That Larned’s venture had the full support of the United States National Lawn Tennis Association (USNLTA) was obvious in the light of his election to its committee the following year, and it is clear now that he was sent as an unofficial envoy to stimulate interest in a US-versus-Britain match. At the time, the intention of the trip was clear in the eyes of the Americans. The Chicago Tribune reported that Larned’s objective was to ‘secure the consents of half a dozen of the best of the English tennis-players to come to this country next year and compete’, later reporting that when Larned returned with news of British ‘enthusiasm … for an international tournament’, there was ‘no other topic of conversation’.

That same summer of 1896, at around the time that Larned was being hosted in Ireland and Britain, Dwight Davis and his friends were competing in the prestigious tournament at Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, which had a reputation for being more “social” than competitive. Three important men were reported to have had a casual conversation during the tournament, namely E.P. Fischer, editor of the tournament’s popular paper, The Lark, J. Parmly Paret, tennis writer, and Charles Voigt, a leading American lawn tennis devotee, about the possibility of Davis – being the well-connected, model-American millionaire that he was – getting more involved in the sport. Voigt proposed, rather auspiciously it would seem: ‘Why don’t you people get him to do something for the game? Put up some big prize or cup?’. Voigt had in mind a series of international exchanges between the US and Britain, and was sure that if put correctly to the USNLTA and Britain’s Lawn Tennis Association (LTA), ‘the affair would in no doubt soon become a fait accompli’. It is fairly likely that Davis got wind of this conversation, given Fischer’s position as editor of The Lark, which often included comical stories about Davis and his “playboy” reputation. More of Voigt’s role can be read in an earlier edition of Playing Pasts (here).

- Niagara-on-the-Lake, 1896.

It is quite possible, therefore, that discussions about the creation of an international challenge-match (between the US and GB) were happening almost simultaneously on two different continents during the summer of 1896. Connections deepened still further, as over the coming months Larned and Fischer met several times, competing as opponents at tournaments in Norwood Park, NJ and Newport, RI and as teammates in the East-versus-West Challenge at Chicago’s Kenwood Country Club. Subsequent reports claim that they both met with James Gardner, Secretary and Treasurer of the Western Lawn Tennis Association, about the prospect of an ‘international tournament’ scheduled for the summer of 1897 that would pit six of the best British players against six of the best Americans—three from the East and three from the West. Several weeks earlier, moreover, the Chicago Tribune reported that another “international tournament” had been proposed: ‘It is to be one more of the great international contests between America and England. … The tournament will practically be for the world’s championship. The ‘team championship’ held at Norwood Park, would be organized by the wealthy Harper family, of Harper publishing, and be officially recognized by Dwight’s USNLTA and ‘held under its auspices’.

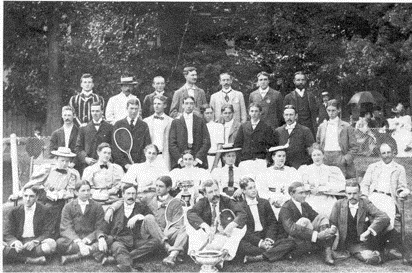

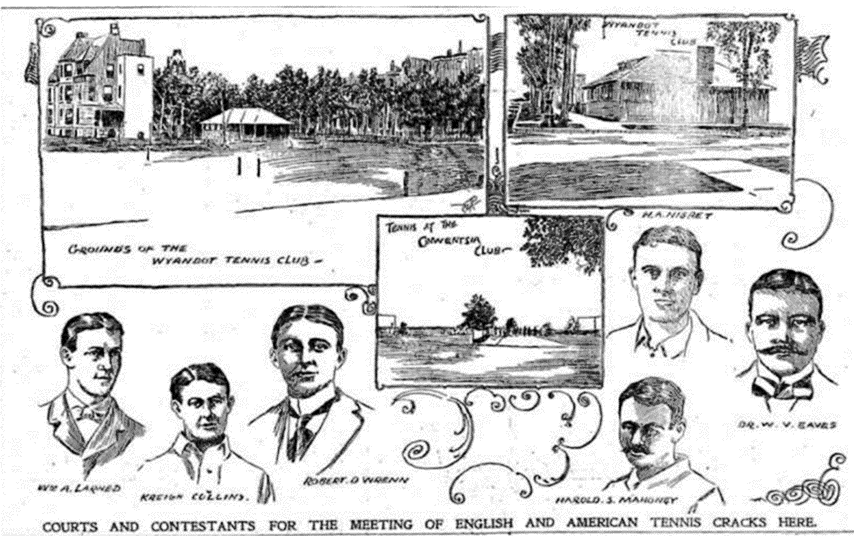

Sensing an opportunity, Dwight then approached the LTA with his idea for an international competition, but the particulars of Dwight’s offer – which included paying the travel expenses of the British players – offended the LTA on the grounds of pure amateurism. Subsequently, they declined. Nevertheless, three of Britain’s best ventured west as “unofficial” representatives. Duly taking the bait were Harold Mahony alongside Wilberforce Eaves and Harold Nisbet, who welcomed the opportunity – more in the spirit of goodwill than competitive rivalry – to test themselves against the emerging American talent over a series of east-coast tournaments.

- Eaves, Nisbet and Mahony’s visit to America in the Summer of 1897.

Of this trip, only Eaves performed well – reaching the challenge round of the US Nationals – prompting the Americans to declare they had won the greatest contest in the history of sport and had not only reached par with the English but had outplayed them and could claim superiority.

After years of complacency, it seemed the British had finally met their match against the Americans and could no longer deny them the opportunity of an official challenge match. Work then began for a reciprocal tour to Great Britain for 1898, which included a proposed US-versus-GB challenge-match to be held in Newcastle, involving Larned and the reigning and four-time US Nationals singles champion Bob Wrenn. Just days before their scheduled departure, however, pressing ‘business engagements’ forced Larned and Wrenn to pull out, and owing to several other top Americans being called for duty in the National Guard, the proposed match was never played. The following summer – owing to wars in Cuba, the Philippines and South Africa – was equally problematic for the best players of both nations, but it was abundantly clear that by this stage, due to the work of Dwight, Goodbody, Mahony, Larned and company, the groundwork had been firmly laid for the establishment of an international competition between the US and GB. Crucially, Dwight Davis was not in any way involved in this process. Nevertheless, it was that summer when the young man toured the west coast and had his famous “epiphany” about an international contest.

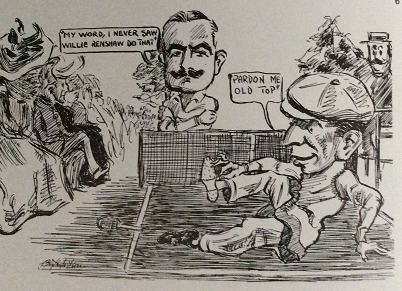

- Dr Wilberforce Eaves contemplating Bob Wrenn’s ‘ungentlemanly’ tactics in 1897.

Davis: Manipulating the USNLTA to Accept his Cup

The story and the intrigue, however, do not end with Davis’s donation. His questionable character and apparent propensity to bend the odds in his favour, manipulate other people and situations to his advantage, and pass off the ideas of others as his own, are revealed in his subsequent actions involving the actual formal “acceptance” of the Cup.

Just twelve days after Dwight Davis was grandfathered onto the USNLTA executive committee in February of 1900, he supplied a crucial vote – on a committee of just five members – on whether or not to accept the donation of his own trophy. This represented a clear conflict of interest, but as far as James Dwight was concerned, this breach of ethics was circumvented by Davis proffering the cup “anonymously”; the cup’s donor apparently ‘desired his name withheld’. With Dwight and Davis in support, the Cup needed only one more vote from the three remaining members, which it duly received, but the following day, Davis’s name was revealed in The New York Times as the competition immediately became referred to as: “The Davis International Tennis Cup”. Undoubtedly, if Davis was truly determined to remain anonymous he could have insisted the trophy not bear his name, and/or shared authority over the competition equally with his USNLTA committee colleagues, but he did neither. He demanded that he, as the donor, be consulted on any proposed changes to the competition and stipulated that if no challenge was made for five years, the trophy must be returned to him. The fact that he demanded these powers calls into question his apparent desires to remain anonymous. His philanthropy had caveats.

The actions of Davis, a well-connected and wealthy future politician, depict a conceited man of tremendous ambition and political capital. After publishing in 1907 his personal reflection on how the Davis Cup came to be – whereby he overstated his own involvement and failed to credit the efforts of others in establishing the necessary friendly Anglo-American relations – he then waited until 1931 before reiterating his original account. By this time, despite alternative versions of events being published – e.g. by Charles Voigt in 1912 – all those who may have refuted Davis’s claims were either dead or incapacitated. Dwight passed in 1917, Larned committed suicide in 1926 after a long battle with depression from acquiring spinal meningitis, Mahony died from a bicycling accident in 1905, Eaves passed in 1920 and Voigt in 1929; Fischer was sectioned in a mental asylum in 1920 after being embroiled in the infamous Wall Street bombing scandal. Davis was by all accounts “home free”!

Davis’s involvement in the establishment of the Cup that bears his name was based on a single act. While he may have had a say in the competition’s developing structure of mixing singles and doubles matches – though these had been experimented in earlier team competitions – we know he also solicited the help of several others including James Dwight for this purpose. Most crucially, however, it is certain that Davis did not help establish relations with the British or invite them to compete for his trophy, nor did he conceive the original idea for international team-based competitions. Credit here goes to the efforts of several gentlemen, notably: Dwight and Larned, but also Voigt, Goodbody, Mahony and Fischer.

One may still ponder why others did not come forward with refutations of Davis’s efforts. A large part of the reason for that might be to do with the insecurity that many Americans felt about their nation relative to others, particularly Great Britain, at the time, and the potential value they saw in Davis as the face of the competition and as an embodiment of a particular national and class ideology. Davis’s wealth and lineage lent tennis credibility in the US, at a time when its officials and players played second fiddle to the British. He was a “model American” and his achievements were lauded over those of other men, who were no match for the charming, handsome multi-millionaire: Dwight was too modest to claim ownership; Larned was not “front-man” material either, due to his declining health; Voigt and Fischer were not sufficiently part of the “establishment”; and, Goodbody and Mahony were British/Irish. The competition needed an American figurehead of Davis’s background to draw British interest and the attentions of the American public and press. From a prominent family in St. Louis, Harvard-educated, prolific sportsman, decorated war-hero, philanthropist and later politician, Davis was the very image of what the WASP establishment wanted to express as quintessentially “American”. However, the well-trod story of Dwight F. Davis, and the origins of the tennis competition that bears his name, is as charming as it is untrue. Davis did not invent the Davis Cup, nor did he conceive the original idea for it. And, underneath the all-American facade, his actions and political manoeuvrings demonstrate ethically-questionable personal motives and traits that defy his positive image.

Article © Simon Eaves & Robert J Lake