Resistance to the use of professional coaches in British athletics during the first half of the twentieth century has been well documented[1] and an ongoing preference for amateur coaching from one’s peers was clearly evident in the year before the Berlin Olympics. In February 1935, a number of amateur coaches were appointed to instruct at the Loughborough summer school for athletics, including R. St. G. Harper for hurdles, J. Cotter for the javelin, J.E. Lovelock for running events, M.C. Noakes for the hammer, R.L. Howland for the shot put, and R.W. Revans for the long jump.[2] Howland was a classics don at Cambridge and holder of the English Native shot put record from 1930-49. In the 1928 Olympics he was 20th and he won silver in the 1930 and 1934 Empire Games. Revans had competed at the 1928 Games in long jump (32nd) and won medals in long and triple jumps at the 1930 Empire Games. Having studied astrophysics at Cambridge he won a scholarship to Michigan before returning to Cambridge as a fellow. During his lifetime, he worked with five Nobel winners and he later became the first professor of industrial management at the University of Manchester.

- Figure 1. The winner of the long jump in the inter-college competition at Cambridge: R.W. Revans who cleared 21ft 9in for Emmanuel. Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, Saturday 15 February 1930, 5.

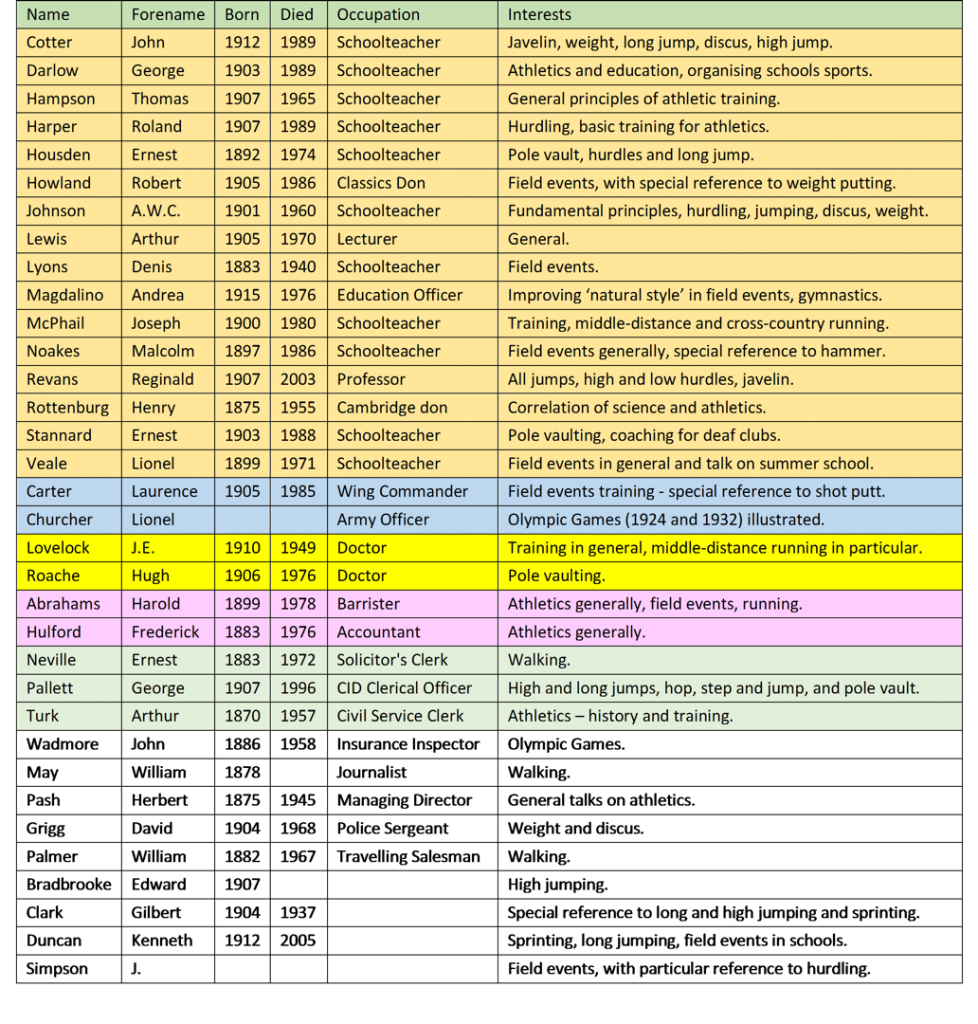

All six men appeared again later that year in a list of amateur athletes and officials willing to give talks, lectures and demonstrations to clubs and schools (see Table 1). Being keen amateurs and volunteers, no fee was to be charged for their services, although it was expected that out-of-pocket expenses would be met. Applications for their services were to be made directly to them and they should be informed of any facilities available for showing films and/or slides. Clubs were reminded that the AAA’s films and slides could be loaned to illustrate lectures given by people who were not on the list.[3]

- Table 1. List of Volunteer Lecturers, Manchester Guardian December 13, 1935, 3

In many ways the composition of this list reflected the traditional profiles for amateur coaches in this period who came from educational institutions, the armed forces, medicine, law and finance, as well as other non-professional middle-class occupations. For these men, coaching was a hobby and they lacked the resources and knowledge to be able to match their coaching counterparts in America, who were career coaches dedicated to producing Olympic victories. Many of them also acted as administrators, diluting further the time that they could devote to coaching. Ernest Neville was honorary secretary of Surrey Walking Club and president of the Race Walking Association (RWA) from 1920-22 while William Palmer, who was on the Southern Committee of the AAA, was president of Herne Hill Harriers between 1921-22 and a walking judge at the 1936 and 1948 Games.[4] Herbert Pash was honorary secretary of Essex County Cycling and Athletic Association from 1908 to 1920 and then chairman. He was made AAA life vice president in 1934 and president of London Athletic Club in 1935.[5]

- Figure 2. H.F. Pash

Some of these men were also involved in Olympic administration. John Wadmore was manager of the 1928 Olympic Team, while Arthur Turk, known as the ‘Grand Old Man’ of British athletics and a life vice-president of the AAA, was in charge of the 1932 and 1936 Olympic teams.[6]

- Figure 3 A.S. Turk

- Figure 4 J.F. Wadmore

Frederick Hulford was the world’s most respected authority on starting. He was chief starter at the 1934 Empire Games and the 1948 Olympics, and he also coached the starters for the 1952 and 1956 Games. Denis Lyons was the first chairman of Gloucestershire AAA in 1925, president of Midland Counties, and an international referee at Amsterdam and at the 1930 Empire Games.[7]

- Figure 5. Dennis Lyons

Despite their amateur status it would be a mistake to assume that there was a lack of vision among this group about how coaching should be organised and what the future might be. Joseph McPhail became secretary of the Southern Counties Coaching Committee after World War I and organised Essex Young Athletes Courses, along with Pash and Turk, as well as sitting on the Essex Coaching Committee, chaired by Kenneth Duncan. Arthur Lewis was on the list of honorary coaches for the West Midlands at Loughborough summer school in 1947 and by 1960 he was a lecturer at Loughborough.[8] Malcolm Noakes served as chair of the AAA coaching committee, while George Pallett, a president of Herne Hill Harriers, was a fully qualified AAA coach at all field events.[9]

Perhaps the most influential individual in the long run was Roland Harper, who represented Oxford vs. Cambridge in both high and low hurdles and was a finalist at the 1930 Empire Games and a semi-finalist at 1932 Olympics. The director of physical education at Manchester University, he was instrumental in setting up Christie Athletic Club with Leeds, Liverpool and Manchester Universities in 1950 and he was a driving force in the introduction of the AAA coaching scheme on 12th October 1946. Harper initially served as Honorary Secretary before succeeding Noakes as chair of the Coaching Committee that appointed professional Geoff Dyson as AAA chief coach on 17th February 1947. It was this appointment that paved the way for the engagement of further professional national coaches and, despite the trials and tribulations of the next few years, Harper can be viewed as something of a visionary in terms of British athletics coaching.[10]

Article © Dave Day

References

[1] See Day, D. (2017). The British Athlete “is born not made” Transatlantic Tensions over Sports Coaching. Journal of Sport History, 44(1), 20-34; Day, D. (2013). ‘America’s ‘Mysterious “Training Tables”’: British Reactions and Amateur Hypocrisy’. Sport in History, 34(1), 90-112; Day, D. (2012). ‘Massaging the Amateur Ethos: Professional Coaches at Stockholm in 1912’. Sport in History 32(2), 157-182.

[2] Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, Tuesday 5 February 1935, 19.

[3] List of Volunteer Lecturers, Manchester Guardian, 13 December 1935, 3.

[4] Illustrated Police News, Thursday 20 May 1915, 10.

[5] Chelmsford Chronicle, Friday 17 August 1945, 5.

[6] Star Green ‘un, Saturday 10 August 1957, 8.

[7] Gloucestershire Echo, Saturday 10 August 1940, 3; Evening Despatch, Friday 9 August 1940, 5; Birmingham Daily Gazette, Thursday 8 August 1940, 3; Birmingham Daily Post, Thursday 8 August 1940, 4; Birmingham Mail, Wednesday 7 August 1940, 5.

[8] Western Times, Friday 8 September 1933, 10.

[9] Dorking and Leatherhead Advertiser, Friday 2 June 1939, 2.

[10] Achilles Report 1989; for a more detailed discussion see Day, D. and Carpenter, T. (2016). A History of Sports Coaching in Britain. (London: Routledge).

![Switching from Women’s Football to Cross-Country: <br>The History of Gruppo Sportivo Giovinezza [Milan, 1933-37]](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/PP-banner-maker-440x264.jpg)

Dennis Lyons was my grandfather.

He had several sons Dennis , Vincent and Kevin . Kevin was my father.

Dennis Lyons had a daughter called Molly .

I knew that Dennis was a runner and was involved in the Olympic Games around 1920.

He and his family originated in Tipperary I understand.

It would be lovely to find out more about him.

Jane Lyons

I am Vincent’s granddaughter. Family in America have done a LOT of research and it’s all on ancestry dot com.