In 1856, Scottish diplomat and erstwhile MP, David Urquhart, and Irish physician and hydropathist, Richard Barter, built an experimental hot dry-air-bath, the first in the British Isles since the Roman occupation. It was not successful due to their being unable to heat the air sufficiently to be an effective therapeutic treatment. Barter improved this early bath after sending his architect to examine the ruins of the thermae in Rome, a pattern which Urquhart also used as the basis for the first so-called Turkish baths which were built on the British mainland.

- David Urquhart (1805-1877) and Dr Richard Barter (1802-1870)

- Display advertisement for England’s first Victorian Turkish Bath built by Urquhart and his Manchester Foreign Affairs Committee in 1857

The Victorian Turkish bath should, more accurately called the Irish-Roman bath, as it still is in Germany and other parts of Europe, while the term Turkish bath is more appropriately used in reference to the hammam, found worldwide wherever there are Islamic communities. For the bather in a Victorian Turkish bath sweats in hot dry air, whereas the Muslim bather washes within the hot rooms, thereby causing the air to become moist and steamy.

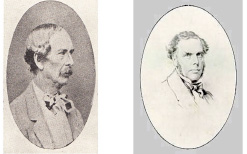

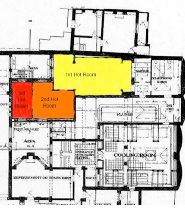

The typical Victorian Turkish bath comprises two or three rooms, each hotter than the previous one. Bathers spend time in each in turn, warming gradually, until they sweat profusely. They then usually take a shower and, if possible, a quick dip in a cold plunge pool. This process can, if desired, be repeated several times before being given a scrub and massage (together called shampooing). The bath is then completed by an important period of relaxation in a cooling-room before returning to the outside world.

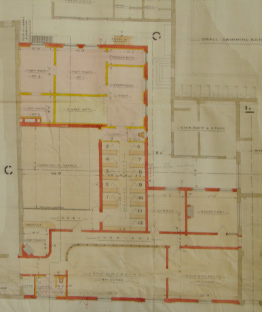

- Plan of Camberwell Council baths, Old Kent Road, London, showing the three hot rooms, 1905

- Shampooing at Wigzell’s Turkish Baths, Oxford Street, Sydney, Australia, 1883

Dr Barter saw the bath as being a therapy where the heat relieved pain from complaints such as rheumatism, for which there was no medical cure. Urquhart saw the bath as the most effective method of achieving personal hygiene when so few homes had running water. The bathers however, often to the dismay of their physicians, found the bath enjoyable, and it gradually became popular as a leisure activity providing the foundation for our own ubiquitous relaxation spas.

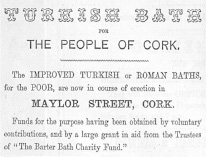

There was early concern that the poor, who were most in need of the Turkish bath, were unable to afford to use them. Dr Barter built two in Ireland specifically for the poor. In Cardiff, the Ladies’ Sanitary Association provided free tickets to the needy. While a third approach was the provision of Turkish baths by companies specifically for their workers and their families.

- The same water would normally be used for all the children at bathtime in the home of a poor family in the 1890s

- Part of a yearbook advertisement for Dr Barter’s Turkish Baths for the Destitue Poor, 1862

While there may have been others, those we know about are those provided by Titus Salt for the workforce at his factory in the company town of Saltaire in Yorkshire, those at the two railway company towns of Swindon and Crewe, and that provided for its staff by the owners of the Wimbledon Theatre in London. [1]

- Cross section of the Turkish baths at 26 Caroline Street, Saltaire, Yorkshire, opened 1863

- One of the hot rooms at the (probably male only) staff Turkish Baths at the Wimbledon Theatre, opened 1910

The Great Western Railway (GWR) had, since 1847, provided an increasingly comprehensive healthcare service—the Medical Fund Society (MFS)—for its workforce and their families, which in the 1940s became a model for the future National Health Service. The impetus to provide a Turkish bath followed a lecture given at the Swindon Mechanics Institute in 1858 by Stewart Erskine Rolland, a close colleague of David Urquhart. Later, some of those present asked whether the company would provide Turkish baths at the Institute, which already had eight slipper baths. The company agreed, provided it was paid for by the fund. But the fund, which was required to be self-supporting through its members’ dues, could not afford to do so.

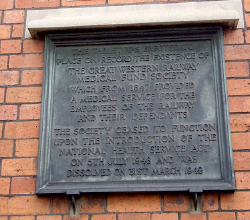

- Exterior wall plaque at the Swindon Baths, Taunton Road

- Slipper Bath at Birmingham, Circa 1912

By 1862 it was recognised that eight slipper baths, without any showers or changing facilities, were totally inadequate for the rapidly growing Swindon. A new bathhouse was built behind a nearby building, but when this was converted into a Methodist chapel the baths moved again. In 1868 the new facility was opened on a triangle of land between Faringdon Road and Taunton Street. This time Turkish baths were included and the whole establishment was leased to a Mr William West who had not only managed the earlier slipper baths, but had also, on his own account, opened a small Turkish bath at his home.

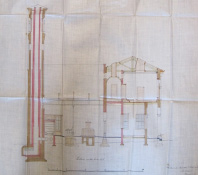

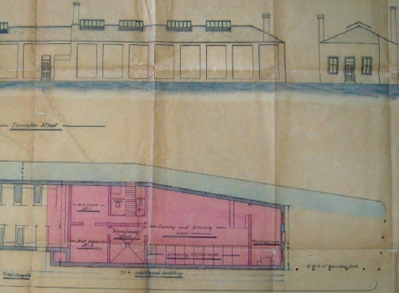

- Plan and elevation of the first Turkish baths at Swindon, opened 1868

The Turkish baths had two hot rooms, a shampooing room, and a cooling-room with nine changing cubicles. They were open from 6am till 9pm on weekdays, from 2 till 9 on Saturdays, and were reserved for women for three hours every Wednesday afternoon. There were two prices for members, presumably to separate the workers from their supervisors and managers.

By 1878, leasing the baths ceased, and the new manager became a paid employee. Opening hours were shorter, from 1pm till 8pm daily, but for society members and their families, they were now free.

In 1891, the GWR built a large red brick building opposite the existing baths, to house a new dispensary, treatment rooms, and separate swimming pools for men and women. New Turkish and slipper baths, with their own entrance round the corner, were added in 1904 to bring both sets of baths together.

- The new swimming baths at Swindon, 1890s, is still open

- The entrance to the second (1904) Turkish baths at Swindon, 100 years later

The men’s Turkish baths were well designed, and although there have been alterations, the structure and appearance of the three original hot rooms remain virtually unchanged. The shampooing room had two marble slabs and a circular needle shower, continuing in use until the 1990s. The mosaic floored cooling-room was particularly spacious.

- Plan of the men’s (1904) Turkish baths

- View into the hottest room, early 21st century

- The men’s cooling room, 1940s

The women’s baths were smaller, with only two hot rooms leading off the shampooing room, with its slab, needle shower, wash basin, and drinking fountain. A cooling-room, toilet, and six dressing cubicles completed the suite.

- Door to women’s (1904) Turkish baths, designed and made by the GWR’s Mr Rice

Although the Swindon Turkish baths successively occupied premises on each side of Faringdon Road, and were run by a series of managements, they are the longest surviving Turkish baths establishment in the world. How ironic, therefore, that in 2016, in a town housing the headquarters of Historic England, English Heritage, and the National Trust, the company contracted by the local council to run them, announced plans to close them, gut them, and replace them with flats.

Crewe was also a railway town, with an 1865 population of between 12,000 and 13,000, most of whom were railway workers, or dependent on the London & North Western Railway Company (LNWR). Almost all the town’s facilities were provided by the company, from houses, to cooking facilities for the unmarried, from churches and chapels to schools and public baths.

The first bathing facilities—slipper baths for men and women—opened in 1845, and were managed by a subcommittee of the Council of the Mechanics Institute. By 1862, the company had expanded so rapidly that the baths were now surrounded by the railway works, and access was difficult for workers’ wives and for the general public.

So new public baths were built by the company at the northern end of Mill Lane (later Mill Street). They consisted of hot, tepid, and cold baths, showers, and an open-air swimming pool. This was fairly basic, as was then the norm. Water was changed once per week, and ‘the price of admission was reduced as the water became progressively murkier’.

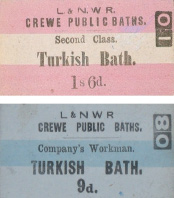

It is not known when the Turkish baths were added, but they first appeared in a local directory in 1874. Although the pool was open from six till nine on Sunday mornings, and till nine o’clock in the evening during the rest of the week, the Turkish baths were closed on Sundays, and otherwise, were open from ten till twelve in the morning, and from two till seven in the evening. Entrance tickets were produced using the same type of machine that printed the company’s train tickets.

- Exterior of the Crewe baths in Mill Lane, late 19th century

- Entrance tickets for the Crewe Turkish baths, c.1870s

Unfortunately, we know far less about these baths than about those of the GWR. The LNWR became part of the London, Midland, and Scottish Railway (LMS) in 1923, and continued running the baths for another 13 years, although its open-air swimming pool was already inadequate for a town of the size and importance of Crewe.

Elsewhere, bathing facilities were provided by the local authority, so the company understandably saw no reason why it should pay for a more modern facility. Crewe Corporation finally agreed to provide new baths in the mid-1930s.

The LMS offered to sell them the existing baths for £500, but the corporation felt the site was too small. The baths closed on 31 March 1936 after serving the town for seventy years. The new bathing establishment was built elsewhere, and without Turkish baths.

This account of the two companies’ provision of Turkish baths for their workforces was intended to contrast the apparent provision of baths by the LNWR solely for the enjoyment of their workers with the GWR’s provision of baths as part of a health-oriented service. But a more relevant contrast has proved to be the difference between the minutely detailed documentation relating to the Swindon baths and the seeming lack of information about those at Crewe.

So no evidence has yet been found to confirm that the baths were actually seen differently by the two companies. Further research is much needed.

Article © Malcolm Shifrin

[1] See: Shifrin, Malcolm Victorian Turkish Baths (Historic England, 2015). Chapter 16 deals more fully the four company baths, Dr Barter’s baths for the poor, and other approaches to providing Turkish baths for the poor.

Hi Malcolm,

Thanks for this excellent account.

I’m intrigued by one detail – you state that the (then) LMS baths in Mill Street Crewe closed on March 31 1936. When I was researching the closure date, the only reference I could find was in the Crewe Chronicle of April 3 1937 which stated “The LM & S Railway Company Baths at Crewe were closed down today…”

I wondered if you could direct me to the source of your date so I can pursue my interest a little futher?

Thanks!