In the late nineteenth century, the middle classes assumed control of sport and their amateur values influenced the future direction of British elite performance. Part of the amateur creed was a rejection of specialised, professional coaching and this has led commentators to assume that Olympic participation before the Great War (1914-1918) was pursued by individuals who rejected systematic training regimes and professional coaching. The concept of amateurism, however, was always more fluid than this. An elite athlete may never have accepted money for competing but could still enhance their social capital through their sporting reputation and this article highlights some of the individuals who helped athletes prepare for the Games at Stockholm in 1912.

These coaches were not the first of their kind by any means and a number of artisan coaches had sustained careers in sport, despite their marginalisation by the amateur establishment, mainly because professional coaching remained highly skilled and specialised. Spencer (Sam) Wisdom, trainer to sprinters Henry Hutchins and 1908 Olympic champion Reggie Walker, had been a plumber in 1881 but described himself as an athletic trainer in both 1901 and 1911, while Harry Andrews trained athletes, swimmers and cyclists and later became trainer to Olympic teams.

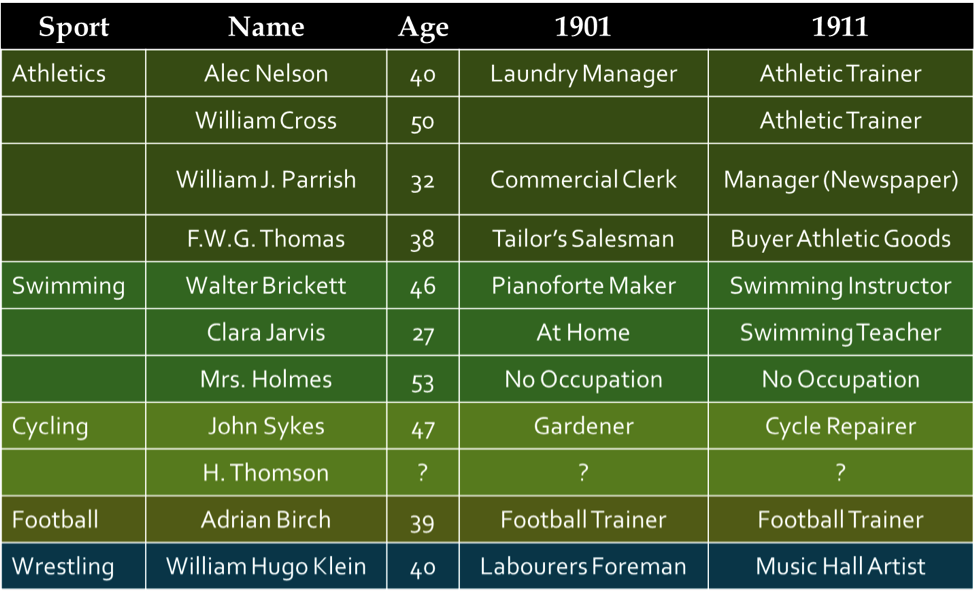

A focus on improving performance through training accelerated with the growth of Olympic rivalry and in 1912 the British team was accompanied by men with extensive coaching experience, some of whom were amateurs. Harcourt Gold, a ‘gentleman of private means’ and ‘leader’ of the rowing team, had coached the Oxford boat race crew from 1906, and the eights that won in the Olympics in 1908 and 1912. The team was also attended by eleven professional trainers. Cycling trainer John Sykes progressed from being a labourer to becoming a cycle repairer over the course of thirty years while the football trainer was Adrian Birch, who began his working life as a shipyard labourer. Prussian born wrestling trainer William Hugo Klein, a music hall artist in 1911, had helped train weightlifter Launceston Elliott, Britain’s first Olympic champion, in 1896.

A focus on improving performance through training accelerated with the growth of Olympic rivalry and in 1912 the British team was accompanied by men with extensive coaching experience, some of whom were amateurs. Harcourt Gold, a ‘gentleman of private means’ and ‘leader’ of the rowing team, had coached the Oxford boat race crew from 1906, and the eights that won in the Olympics in 1908 and 1912. The team was also attended by eleven professional trainers. Cycling trainer John Sykes progressed from being a labourer to becoming a cycle repairer over the course of thirty years while the football trainer was Adrian Birch, who began his working life as a shipyard labourer. Prussian born wrestling trainer William Hugo Klein, a music hall artist in 1911, had helped train weightlifter Launceston Elliott, Britain’s first Olympic champion, in 1896.

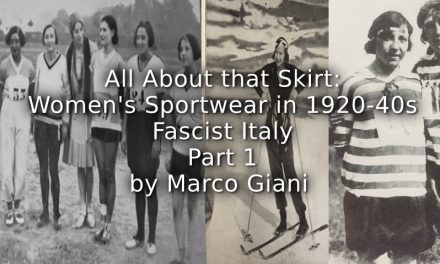

Professional Trainers at Stockholm in 1912.

Four men, all of whom had been involved in preparing the team, were appointed to supervise the track and field athletes. William Cross, son of a Turkish bath proprietor, had used this name when competing as a professional but appeared in the 1911 census as a trainer under his real name of William Lock. William James Parrish, was being employed as a manager at a newspaper by 1911 at which point he was also training athletes at Blackheath. Frederick William George Thomas had been engaged as marathon trainer from June until the end of the Games for £10-12, plus expenses.

A ‘buyer in athletic goods’ in 1911, his first training job had been in 1906, when he was engaged by Herne Hill Harriers, but he is best known for coaching Oxford University. Chief athletics trainer Alec Nelson was calling himself a self-employed trainer in athletics in 1911 by which time he was being employed at Cambridge University. One writer observed that that there was no-one better qualified to look after the British athletes in 1912 and athletic officials agreed but they were faced with some initial difficulties since he wanted a retaining fee of £150 per annum for four years and would only be available from April to the end of September. The compromise was to engage him for £50 for two months from 1st June to prepare athletes and accompany them to Stockholm.

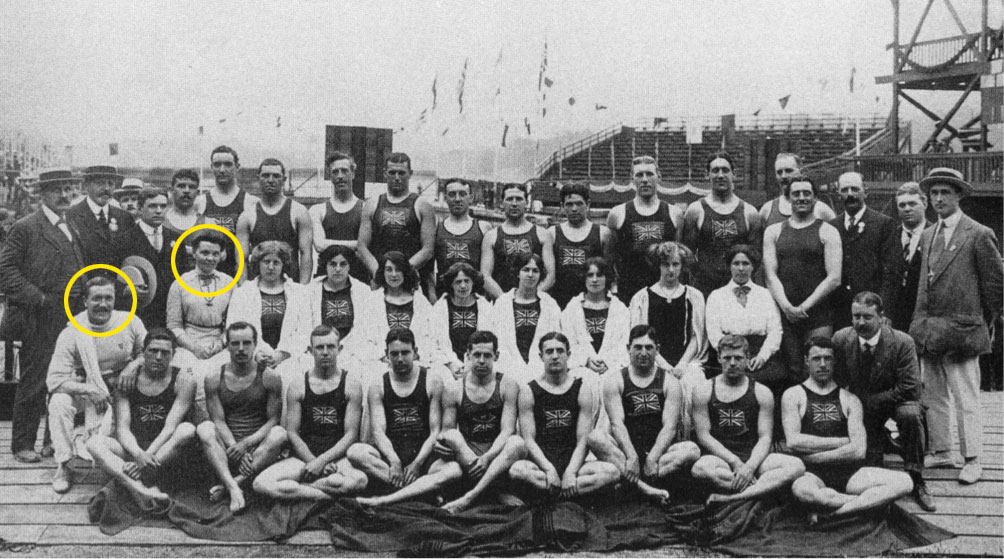

Swimming ‘Professor’ Walter Brickett had followed in his brothers’ footsteps by becoming a pianoforte maker and he had been involved in the creation of the Life Saving Society in 1891. In 1908, Walter was appointed trainer to the Olympic team. Following the Games, he was presented with a testimonial, signed by over seventy members of the Committee, water polo, swimming, and diving teams, expressing their appreciation. After women’s swimming events and a diving contest were included in the 1912 Olympic programme, Clara Jarvis was appointed to accompany the team. Twenty-seven-year-old Clara was a swimming teacher by 1911 and swimming instructress to the Leicester, Loughborough, Burton, Coventry, and Hinckley Ladies’ swimming clubs. Although Clara held the RLSS Diploma and the ASA professional certificate, she is often noted as a chaperone rather than a coach even though she had coached Olympian Jennie Fletcher to six ASA 100yd titles and several world records since 1906. Brickett was reappointed for Stockholm as ‘trainer and adviser-in-chief’ and the committee report following the Games commended both Clara and Walter, ‘professional trainers and attendants’, for discharging their duties ‘in the most capable manner’.

Swimming ‘Professor’ Walter Brickett had followed in his brothers’ footsteps by becoming a pianoforte maker and he had been involved in the creation of the Life Saving Society in 1891. In 1908, Walter was appointed trainer to the Olympic team. Following the Games, he was presented with a testimonial, signed by over seventy members of the Committee, water polo, swimming, and diving teams, expressing their appreciation. After women’s swimming events and a diving contest were included in the 1912 Olympic programme, Clara Jarvis was appointed to accompany the team. Twenty-seven-year-old Clara was a swimming teacher by 1911 and swimming instructress to the Leicester, Loughborough, Burton, Coventry, and Hinckley Ladies’ swimming clubs. Although Clara held the RLSS Diploma and the ASA professional certificate, she is often noted as a chaperone rather than a coach even though she had coached Olympian Jennie Fletcher to six ASA 100yd titles and several world records since 1906. Brickett was reappointed for Stockholm as ‘trainer and adviser-in-chief’ and the committee report following the Games commended both Clara and Walter, ‘professional trainers and attendants’, for discharging their duties ‘in the most capable manner’.

The exploits of these working-class professional trainers remain largely unrecorded since they lacked a public profile and access to resources and, as a result, sports historians have adopted the top down approach to sport by relying on the records of prominent men and women rather than exploring below the veneer and rhetoric of amateur sport. By understanding the lives of those engaged in making a living from sport a better picture can be achieved of what amateurism meant and how it was applied. For example, the tendency has been to view the failures at Stockholm as a turning point in British approaches to coaching and training but the lives of men like Nelson and Brickett suggest that the 1912 Games was less of a watershed and more of an acceleration in an already existing trend. Nelson and Thomas both had long careers at Cambridge and Oxford respectively, although archival material reinforces the influence of patronage and the ongoing master-servant relationship between themselves and their athletes. Walter

Brickett’s social networks and specialist knowledge established him as a respectable artisan and his appointment as Olympic trainer in 1908 and 1912 highlights the opportunities afforded to coaches by the creation of formal international competitions but it also emphasised that the final decisions always needed to be left to the man who knew best, the amateur athlete.