In August 2013, when I was watching England A fielding against Bangladesh A at Taunton, and the England all-rounder Ben Stokes shouted the f-word at the top of his voice so that the whole ground could hear, I first thought of swearing in sport as worth studying. In November 2014 came Australian captain Michael Clarke’s notorious swearing and threat to break England batsman James Anderson’s arm. Swearing, naturally, was not invented in the 2010s. Did men swear in ‘the good old days’? How did hearers and wider public opinion react to it? And why did people do it?

We can explain Clarke’s on-field swearing as the verbal bouncer aimed at the batsman. It’s an aggressive act, with a purpose, to upset the victim and make him play badly. Significantly, Clarke was caught by an on-field microphone and broadcast in error. Here is an example of the strange, liminal nature of a field of play – the spectators can see everything in front of them, as in a theatre, but not necessarily hear anything; in Stokes’ case, the crowd was small and quiet enough so that his shout carried; in Clarke’s case, such conversations – because presumably that was not the sole time Clarke swore at opponents – would have stayed secret.

Evidence of swearing is hard to find; in print, because publishers may shy away from printing it; and in oral history, because likewise interviewees may be too embarrassed. Swearing may accompany conflict. The Warwickshire and England all-rounder Dermot Reeve opened his 1997 memoir Winning Ways with five f*** offs in the first four lines, telling of how on the field at Northampton in June 1994 Warwickshire’s star (pardon the pun) batsman Brian Lara swore repeatedly at him. Reeve called it ‘the worst example of player indiscipline I have experienced in my career’ and rightly saw that his ‘leadership was on the line’; ‘I knew that I just had to douse the situation, appear non-confrontational and hope the club’s administration would back me up’. Also making it hard to study swearing is that others remember conversations and situations differently, as Lara did in his autobiography (as Reeve acknowledged).

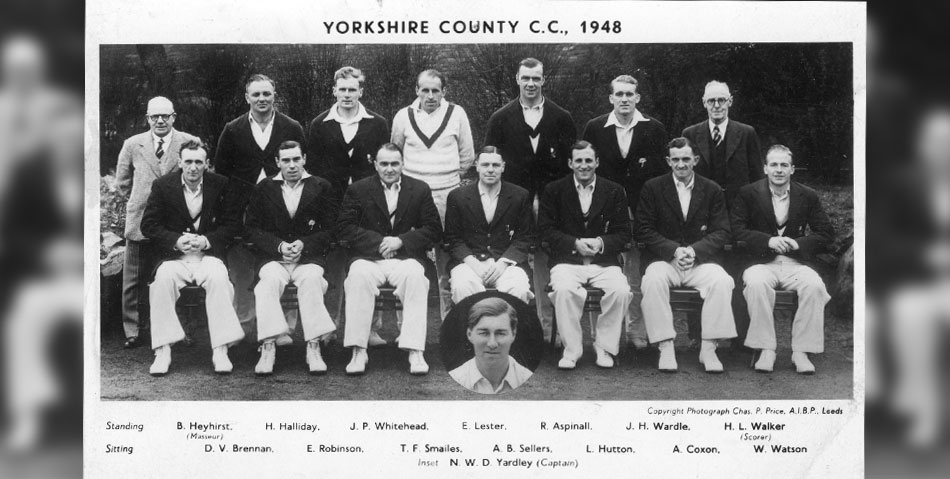

Men swear, then, for the same reason that they use language in general; to let off steam; to make points to others within earshot. As swear-words are taboo, use of them is a challenge to those in power in a group. What then if the captain is the one swearing?! As happened at Northampton (does it always have to be Northampton?!) on Tuesday, August 26, 1947. Yorkshire had beaten Northamptonshire in two days and were setting off for their next game, at Southend. The 24-year-old batsman Ted Lester recalled in old age:

It was a very hot and sunny morning when I boarded the coach wearing a sports coat, flannels and open necked shirt. At the top of the steps stood the skipper [Brian Sellers]. You aren’t getting on this coach dressed like that was his opening gambit. I expressed my surprise as I could not imagine what was wrong. You are not getting on this … coach until you put on a … tie. I was obliged to retrieve my case from the boot and put on a tie before I was allowed to travel down to the south coast. This may seem particularly harsh but having thought about it many times I am sure it was done to ensure that a young colt who had managed to score three successive centuries was put firmly in his place and to quote Brian Sellers was not to let it go to his nut.

Lester – who did keep his place, and stayed with the club as second team captain and scorer – did not tell us the exact swear-word, but otherwise gave insight into when and why Brian Sellers swore. Sellers was then 40, and the ‘most successful county captain of all time’ (Wisden, 1940). His swearing, breaking one social code, here enforced another, dress code. Sellers retired that year and put in four decades as a Yorkshire and MCC committee man; and still swore. The future Glamorgan and England captain Tony Lewis in his memoir recalled Sellers’ ‘intimidating reputation’ and how Sellers greeted him with ‘Na then y’Welsh bastard’. Sellers also swore for the wider public to hear. When I appealed for recollections in the Yorkshire press, towards my biography of Sellers, Brian Dolphin of Sutton-in-Craven recalled an invitation game at Beckwithshaw, near Harrogate, around 1960; Sellers was captain of a team and the umpires were the famous cricketing twins Eric and Alec Bedser. Dolphin recalled Sellers ‘was sat on a seat with some ladies’ when the Bedsers turned up. Sellers said to them: ‘Now you Surrey b****s. How are you?’ Dolphin added: “Later in the game, when Brian had run out one of our players, he said to him “You run as if you have a bat up your a–e!!! He could be quite crude!!!”

Bryan Stott, a Yorkshire batsman of that era, told me that Sellers was uncouth even at winter dinners: ‘If he was giving grace, I won’t tell you what he used to say for grace, it was unnecessary.’ Yet Sellers was privately-educated and could write polite letters. He swore by choice, to impose his coarse character on people. Competitive sport can be coarse; aggressive, dangerous; and disappointing, because for every winner, someone has to lose. Swearing, especially in the private space of the pavilion dressing room, and coach and hotel, is a way for sportsmen to let out their feelings, whether personal (because they have played badly and put their place in the group at risk), team, or a mix of both (some players can do badly and yet their team wins). Sport with the swearing left out is not the whole truth.

© Mark Rowe