Everybody Goes to the Pantomime!

Little Red Riding Hood (1891-92 season)

For Part 1 of this series see – https://goo.gl/xH6FwX , Part 2 see – https://goo.gl/UTL4BB

In William Revill Jr’s recollections of his Grandfather’s production of Little Red Riding Hood at the family owned and operated Theatre Royal and Opera House for the pantomime season 1891/92, we get to see the view of a boy of approximately eight years old

For many years it had been the ‘tradition’ that Christmas Pantomimes across Britain had their first night on Boxing Day, unless Boxing Day fell on a Sunday when the theatre would be closed and first night would be 27th December. Pantomimes could be performed all year round and Easter was also a popular time, but by the 1890s the Christmas pantomime was very much to the fore. The pantomime could run from Christmas until Easter if it was popular, with several new ‘editions’ along the way, for example replacing Christmas jokes with new topical references and ringing the changes amongst the music hall novelty acts. Without the variety of home entertainment available to modern audiences, it was not unusual for people to visit the theatre to see the pantomime several times during its run. By the 1890s shrewd business and advertising managers taking up new roles in the increasingly commercial theatres were looking for fresh opportunities to make more money. They began to introduce another reinvention that helped to ensure that pantomime not only survived but thrived with a shift in the opening night. Increasingly, more and more pantomimes were opening the week before Christmas and then even earlier in December, gradually adopting the pattern of performances more familiar to us in the twenty-first century. This was sound business sense, corresponding better with when prospective audiences were in a holiday mood and already nearby on Christmas shopping trips. In 1891, however, the Revills chose to stay with the Boxing Day to open Little Red Riding Hood. ‘Everybody goes to the Pantomime’ became something of a catchphrase, commonly heard, or read in advertising and reviews.

- Everybody Went to the Pantomime (1893)

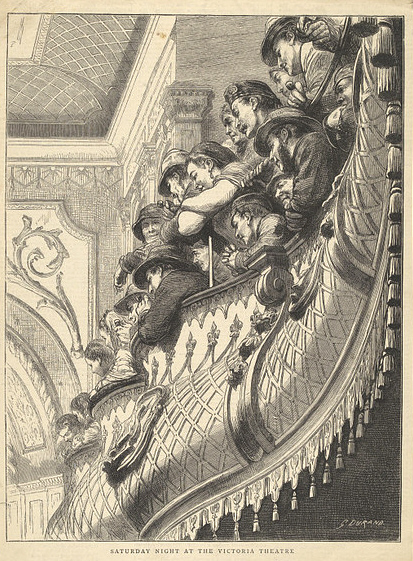

The popularity of music hall, elements of which had been absorbed into the current form that pantomime was taking at that time, reflecting the current taste in British culture. Then, a significant percentage of the British population were experiencing modest rises in income and reductions in working hours that allowed them some disposable income and the luxury of attending entertainment events. This helped to bring about an evolution in the local and national night time economy.

William Revill Jr’s affectionate recollections effectively evoke his Victorian childhood experiences of the rituals of pantomime. Therefore, much of his description of the performance is quoted here as he wrote it, joining excerpts from several of the articles he wrote.

Pantomime … what memories are conjured up by that word, as particularly those readers of my generation will appreciate. How a visit to the theatre was anticipated with glee! We knew in advance the story, which had been told to us by our parents. Then came the big day. The trudging through the snow – strange to say we had no need to only dream of a white Christmas in those days, because it was an actual and regular fact.

We would join the crowd at the early doors for the ‘’GRAND ILLUMINATED DAY PERFORMANCE at 2.00p.m.’’ as the bills announced, no ‘’foreign’’ word like MATINEE was used then. We loved old England, its customs, its names. A crowd of happy smiling faces would be round each door. There were no ‘’queues’’ then, just a jolly, surging crowd. Snow, often a foot deep in the roadway, was gradually being trampled down, and then we could hear bolts being withdrawn inside, and one door would open slowly. A voice would call out ‘’Go steady, please.’’ ‘’1s. early doors. 6d. for children.’’ ‘’Pay box on the right.’’ ‘’Get your money ready and say how many.’’ etc., etc.

Stockport pantomimes invariably ran for up to and more than ten weeks and were sometimes running when the bigger Manchester pantomimes had finished their season.

William J Revill’s pantomimes were noted far and wide in those days, and often ran from Christmas until the end of March. As a matter of fact, a successful pantomime was the cause of William Revill’s death. The audience so liked the show and they came so often that they looked upon the theatre as their own and did what they liked. Just before his death, William J Revill turned the theatre over to my father who would stand no such nonsense

Down we would go to the check taker with our tickets, which were not torn then. There was no Government tax, or ‘’WAR’’ tax then. ‘’War’’ did I say? Omdurman, the death of General Gordon, the affair with the Zulus and the death of the Prince Imperial were still talked about. […] Here we are again, right in the front row of the pit. We had a good seat, a bit hard perhaps, but who cared? We were only here for four and a half hours.

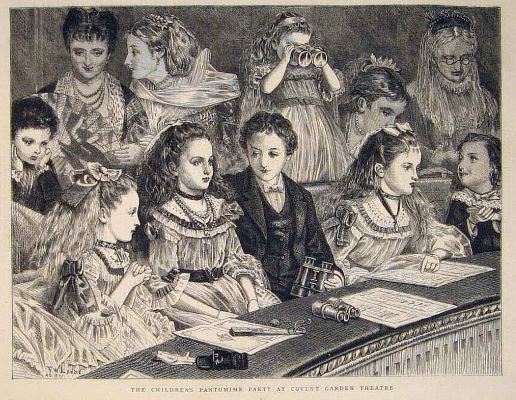

- Middle class children at the pantomime (1870)

Yes, four and a half hours was a typical running time of a Victorian pantomime, especially at the beginning of its run, before the cast and technical staff had fully settled into their roles. Small boys and girls had good value for their 6d in what was often a treat for their only theatre visit of the year. The detail with which William Revill Jr describes the performance, writing in 1958, about an event that had taken place sixty-seven years previously, suggests he had access to a copy of the pantomime book from his family archive. Quite possibly, this was the same copy he had had on his knee as a child. He mentions reading the programme during the interval, which he states was only ten minutes long. The pantomime book contained a vast quantity of advertising, which first began to appear with an occasional advertisement in the much smaller pantomime books of the late 1850s that were literally ‘books of words’ of the pantomime script. It should be noted though, that with so many comedians on stage, by the end of the run the original script often bore little resemblance to what was heard on stage due to all the adlibbing taking place. Included amongst the local businesses advertising he mentions specifically are Winter’s the Jewellers who occupied a large double fronted shop on Little Underbank from 1880 until the 1980s. It became famous as a tourist attraction in its own right because of the automaton clock on the front of the building. Revill also recalls that once he became an adult he himself bought hats from another advertiser:

‘’Found out, Griffith is the cheapest hatter in Stockport’’. Indeed he was! He made my silk hats for me at prices varying from 5s. to 10s. 6d.

- Winter’s the Jewellers, Little Underbank, Stockport

Look out for Part 4 published later this week

References & Notes

Stockport Advertiser, 18th and 25th December 1958, 11th Spetember 1959

The founder of Winter’s, Jacob Winter was a jeweller and clockmaker. After closing as Winter’s The Jewellers, the landmark building became a wine bar. This closed in January 2018 and subsequent plans to reopen as a restaurant have recently fallen through. The building is now owned by Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council who are currently seeking a new use. The clock, which features the characters of Old Father Time, a soldier and a sailor who strike the hours and quarters, is the only one of its type in the UK capable of functioning. It is in good condition, though not in use while the building is unoccupied.

https://www.stockport.gov.uk/rediscovering-the-underbanks/history-and-heritage-the%20underbanks

http://stockportdp.blogspot.com/2013/04/o-is-for-old-father-time.html

Reference to the hatting trade has particular importance here as Stockport was an important centre for the hatting industry. At this time, when everyone wore a hat when they went outside, many of the regular patrons of The Theatre Royal and Opera House would have been employed in hatting production or sales.

Article © Claire Robinson

![Playing Football with the Chorus Girls: <br>Vaudeville Women’s Football in Naples [1931]](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/PP-banner-maker-440x264.jpg)

Hi Claire,

I’m a descendant of William Revill and happened across your articles while looking up information for a school family project for my son. Made for interesting reading.

Thank you,

john