For Part 1 of this series see – https://goo.gl/xH6FwX

Making Little Red Riding Hood

In his first article for the Stockport Advertiser about how his Grandfather and the staff of Stockport’s Theatre Royal prepare for their annual production of the Christmas pantomime William Revill Jr. states that ‘Weeks of preparation are needed before the actual rehearsals take place for pantomime.’ In reality, the production of a spectacular pantomime was effectively a year round job, with some theatres announcing the title of the next year’s pantomime in the souvenir pantomime book. This would be available for the audience to buy as a glorified programme containing the libretto of the performance. In his memoirs, Robert Courtneidge recalled that when he took up his first managerial position at the Prince’s Theatre in Manchester in 1896

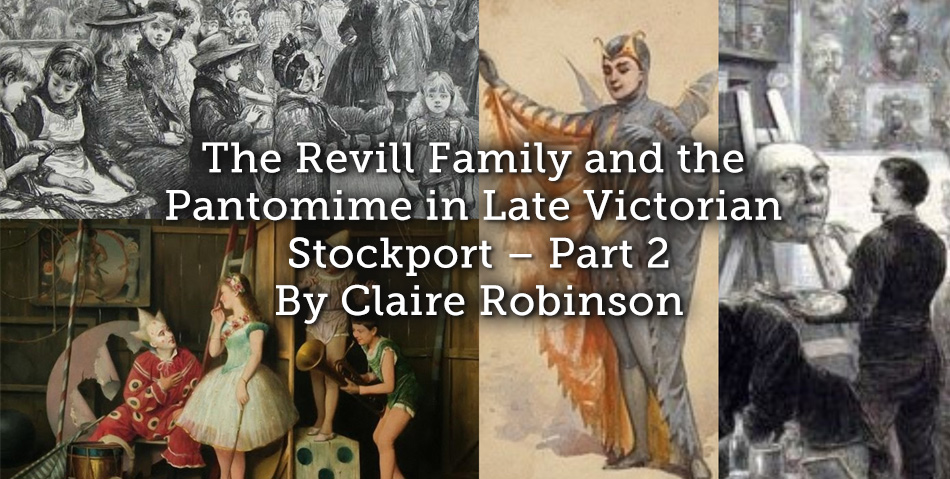

Pantomime was much in vogue at this time, and I endeavoured to make those I produced entertaining alike to both children and grown up people. In company with my friend A. M. Thompson I spent most of the year in drafting and writing the book. With C. Wilhelm, whose delightful designs for the Empire ballets and scores of London productions have never been adequately recognized, and Conrad Tritschler, a painter of genius, my wife and I mapped out the changing scenes that were a great feature of the productions. Backed up by a wonderful staff we produced year by year pantomimes that were successful in attracting record attendances to the theatre.

- Carl Wilhelm’s costume design for the demon ‘Bad Company’ in Dick Whittington at The Olympic Theatre, London (1892)

William Revill Jr. describes his family’s very similar experience in Stockport. For the Christmas pantomime season of 1891/92 William F Revill decided on the story of Little Red Riding Hood.

- Scene from Little Red Riding Hood at Covent Garden (1874)

In building his new theatre in1888 Revill Snr had been keen to incorporate the latest technology as we will see in some his grandson’s reminiscences to be quoted here. His Theatre Royal was well equipped as a producing house, as well as to present incoming touring productions as it did for most of the rest of theatrical year.

Traps

A variety of trapdoors ‘traps’ were installed in the floor of the stage to enable special effects such as the magical disappearance and sudden appearance of characters. The health and safety of performers and stage hands was only just becoming a consideration.

Enoch Wild and Co. had been busily preparing the sinks and rises in the stage floor, through which ground rows, cloths and set pieces would arise and disappear from view in the elaborate transformation scene. The grave trap was in the stage, through which the demon would roll over and disappear from view, suddenly to fly upwards from the star trap. The traps for this particular ‘’Red Riding Hood’’ pantomime I have in mind were arranged by Edgar Martin, one of the Martin Brothers, the famous pantomimists and comedians, who lived for so long in Stockport. We were very proud of our stage equipment in those days. Though trap scenes were used only during pantomime, give us 24 hours notice and they would all be in working order, as they had to be, because lives and limbs depended on their efficiency.

Another famous trap artist, Devereaux Cawdrey, is credited with designing the system of traps for the Revill’s theatre in Ashton under Lyne which opened the year after Stockport in 1889. He was a favourite performer of William J Revill, so it seems likely that he also designed the traps for Stockport.

I remember many fine trap performers. About the best was our local Rolando Martin. Another was Devereaux Cawdrey, whom I once saw shot into the borders and never came down again to the waiting comedians below. He hung onto a bar trapeze, where he sat until the end of the scene!

- Devereux Cawdrey (1834-1898) – Trap Artist

In 1959, William Revill Jr also remembered the use of ‘Limelight’ for stage lighting and special effects.

This, it is interesting to recall, had to be made by the limelight man. It was stored in a very large container outside the building and carried like gas by pipes to the point of burning through lumps of hard lime, which, when lit, burned with a hot flame. Stalls patrons will remember flaming lime which used to drop to the stage off the perches where the lime boys used to sit. Gas, of course, was the usual form of illumination used everywhere in the building.

Giant Heads

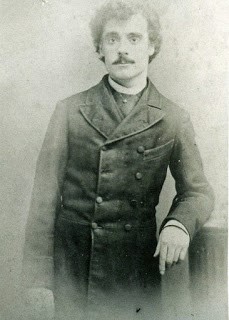

Perhaps less cutting edge technology were the vats of size glue used in the making of scenery and in the case of pantomime, for the production of the ‘giant heads’ made of papier-mache. They represented often grotesque, demonic and comic characters, and being oversized could indicate moods or character traits more easily seen from the back of the auditorium without the use of opera glasses. They were also a useful aid for quick changes. William Revill Jr’s recollection of the making of the glue by boiling down animal bones highlights not just the year round nature of preparing for the next pantomime, but of the problems it could cause, even in summer. Recalling preparations for Little Red Riding Hood he writes:

The weather is hot this June morning, as we get down to brass tacks with our scenic artist, who was Alf T. Brown, in fact, afterwards to become famous as Drury Lane’s Alfred Terrain. The Theatre Royal is equipped with a paint frame and room, as every theatre worthy of the name did have in those days. Paints have to be ordered, the brightly coloured sheen foil paper, and several bolts of canvas for a start. Oh yes, and I must not forget the horrible glue size.

The papier-mache tub at the back of the theatre was now in active work, much to the annoyance of the neighbours in Duke Street. Have you ever lived near a glue factory? The huge heads to be worn by gnomes, etc., were being fashioned, and as they dried they were being painted by the scenic artist.

The fragility of papier-mache and the rough treatment they would have endured during a busy pantomime season, means that no examples appear to have survived to the present day. It is likely any that remained were destroyed at the end of the run as they were unlikely to be needed again and would have taken up a great deal of space in storage. Fortunately for the theatre historian, many images have survived to help us understand how the production looked.

- Pantomime ‘Giant Heads’ being made and stored The Graphic (1870)

Women’s Work

Referring back to Robert Courtneidge’s comment above, about the year round nature of pantomime preparation and in comment’s by other theatre managers on this topic, it is a time when we get to hear about the work of women in theatres, not only as performers, but often in uncredited roles in the management behind the scenes. This is particularly to the fore in family owned concerns. Courtneidge married Rosie Nott who had been an actress before they were married and had children. She was well qualified to take a role in producing the pantomime. His comment indicates that she was involved throughout the planning process.

Costume was an area where women often took the lead. In Stockport, William Revill Jr describes how the women in his family took charge and were also able to coordinate and outsource piecework to local women, many of whom would have had children and other family members appearing on the stage.

The costumes were the worry of the womenfolk, and I can remember the many confabs between my mother and my grandmother, and the hundreds of yards of brilliantly coloured silks and satins – yes, silks and satins, not printed calico. The designs for the costumes were already decorating the office walls. These designs were rather elaborate affairs, about 12 inches by six, beautifully painted and tinselled. As a boy I had hundreds of discarded designs to play with. Women were engaged who had sewing machines at home, no factory work.

- Pantomime fairy costume (1889)

This comment also draws attention to the no expense spared approach and the quality of the production values. This ensured that Revills were able to hold their own in the competition with the theatres in central Manchester and attracted big stars including the like of Dan Leno, Stan Laurel and Charlie Chaplin to perform there.

Auditions

As with managers at other theatres, Mr Revill would negotiate contacts throughout the year to engage the stars of his pantomime, the larger roles, comedians, singers and speciality acts from the music halls. Then it was time to audition locally for the ‘supers’ and children. His grandson remembered.

The company of players was being negotiated and contracts issued stipulating that each member must report for rehearsals two weeks before the production date, when their parts would be handed out to them. The chorus of supernumeraries was made up of six professional show girls and 24 local young women, the idea being for the professionals to lead the locals. Auditions were held almost daily for four or five weeks before, and I assure you there was no lack of applicants for the few shillings a week they were to receive. The musical director must have been sick of “The last Rose of Summer’’ and “I Dreamt I lived in Marble Halls,’’ which seemed to be the staple range of their repertoire.

Then came the applications from the local children with the same ambition as their elders; tall ones, thin ones, fat ones, scraggy ones, all wearing clogs. Indeed, most of the chorus applicants looked as if they were attending an audition for the part of Fanny Hawthorn in “Hindle Wakes.’’

- The Employment of Children in Pantomime (1889)

The Dress Rehearsal

Finally all the elements were brought together for a run through of the show in full costume. In relating all these reminiscences from his childhood, William Revill Jr allowed himself to move forward in time to tell the story of one of his experiences during his own years as the manager of the Theatre Royal and Opera House.

Dress rehearsal night would arrive and it would continue into the early hours of the morning. It had to be right. I shall never forget one pantomime produced by John Walters. The dress rehearsal ran until 1.30am and as the curtain fell I congratulated Walters on a very fine show.

He replied, laconically, “Do you think so, Mr Revill?’’ and turning to the stage shouted out: “Right boys and girls. We will now go right through it again.’’

I would not permit it, however. The stage staff, who had been there since 8.00am the previous morning, were done up, and I had to consider the same night’s show. So we all went home to be up again very early for the big day.

Though some years after Revill Snr was producing his pantomimes, this event is worth retelling, as similar occurrences were happening all over the Britain for years in order to be ready for the opening night.

- In the Wings during the Pantomime

In the third and final part, with opening night having arrived, we will discuss the experience of the first audience to see the new pantomime, and the verdicts given in the newspaper reviews.

Article © Claire Robinson

References

Courtneidge, Robert (1930) I Was an Actor Once. London: Hutchinson and Co. Ltd. pp. 169-170

Stockport Advertiser

The Graphic