‘Swimming isn’t everything; winning is…’

The world in 2016 seemed to focus on Michael Phelps dominating the Olympic Games in the pool, but it is probably worth remembering that he wasn’t the first swimmer to completely own a summer. Mark Spitz takes that distinction when he effectively destroyed all his rivals at the 1972 Games in Munich and thereby set a benchmark for excellence that lasted 36 years. Spitz was planning to become a Dentist once he returned to America after the 1972 Olympics; however his medal haul of seven gold medals, all won in world record time soon put pay to that. On his homecoming he was hailed as the greatest American hero since Lindbergh, one of two faces every person in the USA could name, the other being the then President Richard Nixon and some forty-four years later he still remains an icon.

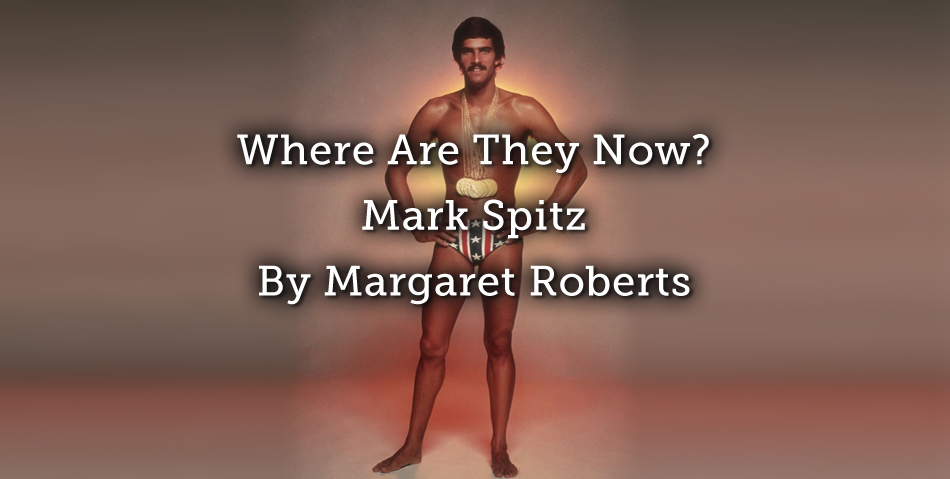

- Mark Spitz in action

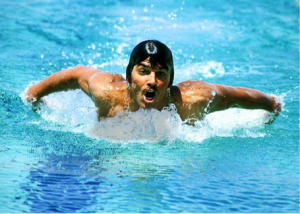

- Mark Spitz

Encouraged by his father Arnold, who often repeated the mantra “swimming isn’t everything; winning is”, Spitz held 17 national age-group and a world record by the age of 10 and was named the world’s best 10-and-under swimmer. The young man continued to excel, especially at butterfly, and in 1966, at 16, he won the 100m ‘fly at the National AUU championship and five golds at the Pan-American games the following year. By the time the 1968 Olympics came around, having already set 10 world records, Spitz was widely expected to take several individual gold medals. The brash and cocky swimmer announced to the world that he would win six, in the end he only won two; both relay medals, to add to his two individual silver and a single bronze. What would have been a major achievement to others was a bitter disappointment to Spitz.

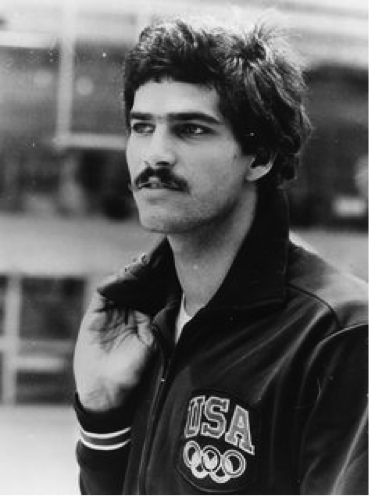

A more mature and focussed Spitz appeared for the 1972 Games, determined to dominate he did just that – making a splash into the Olympic records books some 13 years before Phelps was even born. For a generation he was more than just the most decorated Olympian of all time, he was also the first swimmer to make the transition into that hallowed world – the land of celebrity. Where Johnny Weissmuller paved the way, the 100m freestyle champion won six Olympic titles in the 1920’s and became a Hollywood star in the 30’s and 40’s as Tarzan, Spitz picked up the baton and swam away with it. Lucrative commercial contracts, including Adidas and Speedo as well as requests for appearances on various television shows followed, all helped by his photogenic looks, indeed the photograph of him in his stars and stripes swimming trunks wearing his seven gold medals was made into a poster and quickly made him the hottest pin-up since Betty Grable. Over the next two years he reputedly earned more than $7million as he continued to capitalise on his fame and swimming success.

- The iconic 1972 poster

Still basking in the glow of seven gold medals, Hollywood came a-calling and Spitz almost signed up to be eaten by a shark! Many potential film roles were sent his way and one of the projects he was offered was a film adaptation of a horror novel by a young and upcoming director called Steven Spielberg. Spitz, who had been taking acting lessons, was screen tested for the part of Chief Hooper in the movie Jaws, the part which was re-written without the character’s gory demise, ultimately went to Richard Dreyfus. Spitz felt he failed to get the role due to the fact that, being so close to the Olympics, transcended who he was as an athlete and therefore would be too challenging for the public to separate the two. The Spielberg 1975 blockbuster wasn’t the only well-known film Spitz nearly appeared in. He also had talks about appearing in the Robert Redford-Barbra Streisand drama The Way We Were.

- American swimmers Tom Bruce (left) and Mike Stamm (right) carry teammate Mark Spitz on their shoulders during the medal ceremony for their victory in the men’s 4×100-meter medley relay race

At the height of his fame, the swimmer was known almost as much for his moustache as he was for setting records in the pool. At its peak, his moustache was worth seven figures and was neck-and-neck with Burt Reynolds’ for 1970s supremacy. It took four months to grow, but Spitz was proud of it. He had intended to shave if off for the Munich Olympics but since he did so well at the trials, breaking the 200m ‘fly world record, he decided the moustache was a good-luck charm and it stayed. During a practice swim, Spitz noticed the Soviets photographing him. Asked whether the moustache added unwanted drag, Spitz replied, “No, it actually deflects water from my mouth and allows me to keep my head in a lower position that helps my speed,” His answer, reported in Newsweek magazine, was pure invention, but the Russians didn’t know that and soon quite a few Soviet swimmers began sporting moustaches.

- The famous moustache

Spitz’s bid to become a Hollywood star proved not to be such an overnight success and quickly floundered with critics panning his performances on TV as bland and calls from both Hollywood and commercial clients all but dried up. He managed to maintain a presence as a sports commentator for a few years including a period with ABC Sports starting in 1976. He helped cover both the 1976 and 1984 Summer Olympics, but after that he largely dropped out of the public eye. He managed to divert himself with his new hobby of sailing for a while and eventually he started a real-estate agency in Beverly Hills which proved successful. As the 1980s drew to a close he decided to come of out retirement and return to the Olympic pool for the 1992 Games, unfortunately for Spitz his best time of 58:03 failed by just over two seconds to make the qualifying time for the USA Olympic swim team.

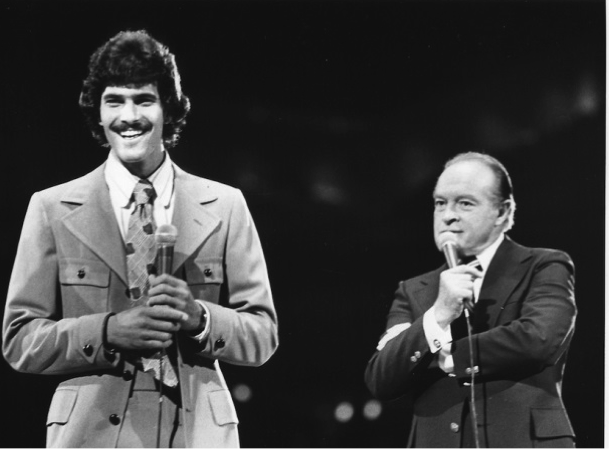

- Spitz on the Bob Hope Show

After retirement Spitz was diagnosed with acid reflux disease and then in 1995 he was found to have abnormally high cholesterol levels. He embarked on a regime of diet, exercise and medication and managed to cut the levels in half. As a paid spokesperson for the pharmaceutical Medco he undertook a national campaign to educate people about the risks of heart disease brought on by high cholesterol. Having given up his real-estate business, Spitz considers himself an entrepreneur and also continues to do promotional work and deliver motivational talks. More recently he has been a regular critic of both FINA and the IOC in their respective battles to keep sport drug-free. In 1998 he condemned FINA for its embarrassing attempts in this regard and a year later lambasted the IOC who, he claimed, had the technology to test for a plethora of drugs but was refusing to do so because of pressures exerted from eastern bloc nations and China.

“Old Olympians just never sort of die, they just sort of fade away.” Spitz once said in an interview with TODAY and certainly that seemed to be the case but then along came Michel Phelps and suddenly Spitz was rejuvenated. Phelps broke Spitz’s record in 2008 by winning eight golds in Beijing and for Spitz it helped put his own greatness into context. In typical Spitz style he told Oprah “I never realised my greatness until Michael Phelps broke my record…what greater accolade could I have left on my sport than have somebody else break my record. So, I relish the fact that I was alive when that happened. ” It upset Spitz that he was never invited to Beijing to watch Phelps attempt break his record. He is quoted as saying “I never got invited. You don’t go to the Olympics just to say, I am going to go. Especially because of who I am…I am going to sit and watch Michel Phelps break my record anonymously? That’s almost demeaning to me, It is not almost – it is.” As a result of this perceived snub Spitz refused to attend the Games, but in August 2014 he clarified his statement saying that commitments for a corporate sponsor stopped him travelling to China and reiterated his pride in Phelps who he said was “…doing a great job for the United States and inspiring a lot of great performances by the other team members.”

- Seven-time Olympic gold medal winner Mark Spitz places a medal on Michael Phelps after the 200m individual medley during the USA 2008 Olympic swim trials

Spitz was present in Rio de Janeiro when Phelps became the most decorated Olympian of all time, his performance at the Games taking his personal medal tally to 28, including a staggering 23 golds. Phelps in turn paid a tribute to Spitz by mimicking the iconic pose with his own haul of Olympic ironware.

- Phelps poses in a tribute to Spitz

Asked recently if he had had an incentive, such as Phelps’ record to chase, would it have impacted his decision to retire after his 1972 success. Given that the rules for amateurism were completely different in those days, it definitely would have been in his best interest, not only career-wise but also for the sponsors to continue in the sport for a number of years that would have led him to the next Olympics in Montreal he replied. However the “$64,000 question is what would I have swum there and the answer is not that many events. That’s arduous to do.” The World Swimmer of the Year 1969, 1971 and 1972, who chose Johnny Weissmuller, Michael Phelps and Matt Bondi to join him as part of a dream relay team has always thought of himself as “…a regular guy”, who “ happened to do something extraordinary in the journey of my athletic career.”

- Mark Spitz is seen in the crowd at the Olympics Aquatic Stadium, Rio 2016

Article © Margaret Roberts