- Cheryl Tiegs, Vitas Gerulaitis, Ilie Nastase and Martina Navratilova at Studio 54, 1979

For many a passing sports fans, and those of a certain age (well, my age) Vitas Gerulaitis is a song by Birkenhead’s finest:-

But, with the recent film release of Borg Vs McEnroe, a biopic of the 1980 Wimbledon Final, some of the players of the era have also been utilised within this period piece. At a recent screening of the film Martin Polley gave a brief talk on the match and its cultural and historical significance. For me, I’m more interested in one of Borg and McEnroe’s shared friends on the circuit, Vitas Gerulaitis. A New Yorker, an Australian Major champion in December 1977 (the only time a major has been played twice in the same year) and a top 10 player. He was also famous for his party lifestyle and especially his regular attendance at the New York hotspot, Studio 54. This brief article will look at the recent film and it’s portrayal and importance of Vitas Gerulatis in the film.

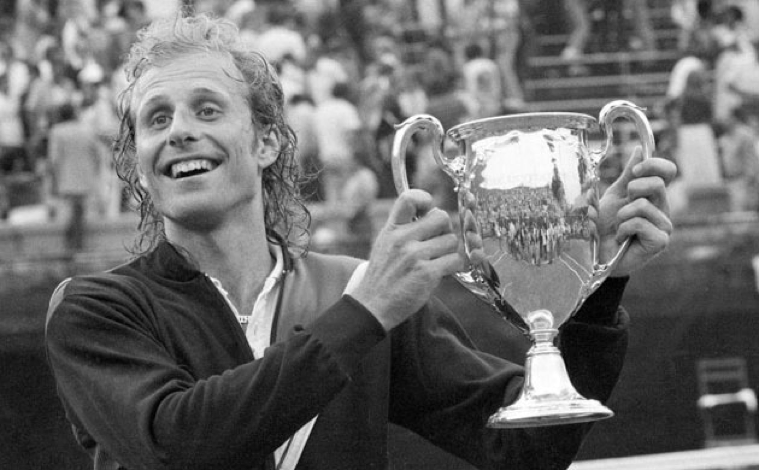

- Vitas Gerulaitis

In many ways The Borg V McEnroe film overplays the role of the two main protagonist in the film (but then, the title leads to that). But this is often how the media represents Sport on Television or film. Whannel (1992) said of the 1980 men’s tournament at Wimbledon and how the tournament was framed on the BBC:-

The central narrative question for the coming fortnight [of the Wimbledon Tournament], namely, ‘who can stop Borg?’, ‘Can anyone stop Borg?’ The men’s singles was treated as much more important than either the doubles or the women’s singles. This raises a complex question: to what extent are hierarchization like this constructed by television [or film], and to what extent does Television merely relay, in reflective fashion, the pre-existent hierarchisation of the Sport itself?

This is a central tenet of the movie also. A construction of the rivalry between Borg & McEnroe surpasses the other stories, and factual accuracy in some cases.

In the film, only 3 other players have genuine speaking roles in the film. These three are Jimmy ‘Jimbo’ Connors, Peter Fleming and Vitas himself. The first two meet McEnroe on his way to 1980 Wimbledon final.

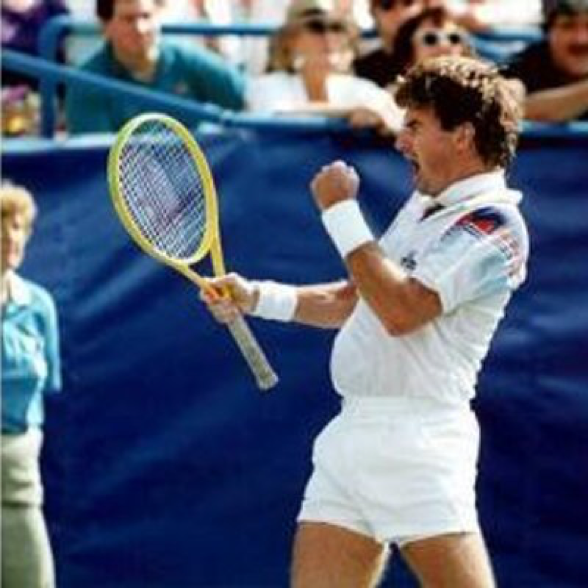

- Jimmy Connors

The presentation of Connors and Fleming within the film act as a counterpoint to both McEnroe and especially Vitas Gerulaitis. Peter Fleming is one of McEnroe’s best friends and, more importantly, his double’s partner. Also, one of the first times we first meet all three together, Vitas has two women draped over him and wants to go with clubbing. McEnroe agrees, but Fleming has to ring his girlfriend and says no. Fleming, therefore acts as our moral compass within the film (he’s the ‘clean’ American). When Fleming and McEnroe meet in the Quarters of Wimbledon, Fleming accuses McEnroe of hiding his ankle support and McEnroe refuses to speak to him. After a heavy defeat, Fleming underlines the importance of friendship and especially the need to be a ‘good loser’ or that McEnroe will never to be remembered as a great for being a bad loser. We are also left uncertain whether McEnroe did hide it, underlining his desire to win at any cost. The advice though McEnroe takes on board in the Final. Fleming has previously underlined that his relationship on court with McEnroe could be volatile, once telling him ‘Just because i’m your friend doesn’t mean i’m the salvation army.’ (Cronin, 2011)

- McEnroe & Peter Flemming

The Jimmy Connors character is actually factually incorrect, as they do meet in the Semi-final and McEnroe tells him to ‘go away’ in no uncertain times on a line call. But the character has a beard in the film. Actually, Connors does not have a beard in the 1980 tournament. Anyway, Connors and McEnroe detested each other at this stage with McEnroe himself saying ‘He got under my skin and I got under his skin too and I don’t blame him…He had a young guy taking away his things, and he’d do everything he possibly could do to make me suffer.’(Cronin, 2011)

Vitas, is the only one of the players we never see play. He’s seen smoking, drinking and womanising in two night clubs. But the two clubs are important. In the film, Vitas takes Borg to Studio 54 in 1978, whilst in 1980 he takes McEnroe to a Annabel’s nightclub in London. In many ways he’s a Falstaff character. A mentor for both but not taken seriously. Also, let us not forget, the film seems to indicate McEnroe is the new pretender in world tennis to Borg. Actually, this, I would argue, is untrue, as the previous September McEnroe won his first major singles title, the US Open. Defeating Vitas in three sets. Vitas, was a player of some talent.

Vitas Gerulaitis has often been more spoken of for his ‘joie de vivre’ and ‘bonhomie’ and his party lifestyle. Again, the film is not factually accurate because Gerulaitis is seen to enjoy champagne, as he swigs from a bottle. Both Cronin and Tignor have emphasised Vitas didn’t like alcohol. Tignor (2012) and Mewshaw (1983) had discussed that Vitas Gerulaitis drug of choice was cocaine, with Tignor discuss how after losing the 1977 Wimbledon Semi-final 8-6 in the final set, he bows afterwards to the Queen, when his half moon medallion hangs out. The medallion is a device used for ‘sniffing’ cocaine from.

His importance to the film in this aspect, is the film shows him taking both to clubs. Since retiring, both have indicated they took cocaine. This is underlined in one shot when Borg is at Studio 54 and he seems to be looking with a heighten sense of awareness, it’s in slow motion and his usual sense of reality is distorted by Studio 54 patrons being in extravagant dress (or undress). These are common trope used in cinema to indicate the use of drugs.

Vitas is also important in discussing a historical aspect of Tennis. The tennis racquet. By 1980, Bjorn Borg was using the Donnay Borg Pro tennis racquet. Whilst at the nightclub with McEnroe, Vitas discusses Borg’s need to have the racquets at the tenses they can be (something Borg discusses in the film). He then checks which racquets are tense enough for him to use. This is actually true, because Borg & McEnroe were still using wooden racquets up to the 1981 US Open final, which would be the last time both players used wooden racquets in a Major final (Tignor). After 1981, players like Ivan Lendl would be using graphite compound racquets as would others, as these racquets would be standardised and more powerful. Also, no need for the below device to stop the wood buckling or constantly getting the strings tightened.

In conclusion, the films minor characters within the film are pointers to the important aspect of how Tennis is represented on screen. It’s a rivalry between Borg & McEnroe. But it is other things also. That players like Vitas are portrayed as a relic of the 1970’s disco and a playboy character, unlike a more ‘must win’, ‘professional’ and ‘individualistic’ outlook the neoliberal era the 1980’s represent and John McEnroe being the vehicle of this portrayal (underlined by McEnroe’s parents feeling disappointed when he gets 96% in a maths quiz). Vitas though, is the unifier within the film. He is friends with both players and the irony of the film is that at the conclusion of the film, we are informed Borg was McEnroe’s best man at his wedding, as if to underline a more human aspect to both men, rather than being sporting rivals. Because that is a ‘positive’ approach to their relationship. But in 1994, they shared another moment together. Both were pallbearers at Vitas funeral, who died of carbon monoxide poisoning aged 40. But ‘real life’ would be too sad for Hollywood.

Article © Les Crang

References

- Borg vs McEnroe. (2017). [film] Directed by J. Metz.

- Cronin, M. (2011). Epic: John McEnroe, Bjrn Borg, and the Greatest Tennis Season Ever. 1st ed. London: Wiley.

- Haden-Guest, A. (n.d.). The Last Party. 1st ed. London: Open Road Media.

- Mewshaw, M. (1984). Short Circuit: Borg, McEnroe and Connors – the Era of Bribes, Match-fixing, and Drugs. 1st ed. New York: Penguin Books.

- Mitchell, K. (2014). Break Point: The Inside Story of Modern Tennis. 1st ed. London: John Murray.

- Owen, F. (2013). Clubland: The Fabulous Rise and Murderous Fall of Club Culture Kindle Edition. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Tignor, S. (2012). High Strung: Bjorn Borg, John McEnroe, and the Last Days of Tennis’s Golden Age. 1st ed. New York: HarperPaperbacks.

- Whannel, G. (1992). Fields in Vision : Television Sport and Cultural Transformation. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Wilson, E. (2014). Love game. 1st ed. Love Game: A History of Tennis, from Victorian Pastime to Global Phenomenon: Serpent’s Tail.

![Introduction to the British Society of Sports History [BSSH]](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Bssh-Banner-440x264.png)

Just finished watching the movie. Enjoyed but didn’t love it. Thanks for sharing your insights into both the fact and fiction of the Borg/McEnroe rivalry.

Cheers for reading and commentating

Anyone notice the scoreboard inaccuracies reflected at the various stages of the final?

Continuity person was shot after the premiere – allegedly!!!

Dude. Thank you. I have met Mac several times, spoken with him, asked him a couple of questions, he signed a large blow-up poster size shot I took of him in ’90 and it has ALWAYS irked me that they keep ignoring Vitas in the Hall of Fame.

http://christopher-king.blogspot.com/2011/01/kingcast-ode-to-vitas-gerulaitis-man.html

http://christopher-king.blogspot.com/2012/07/kingcast-spike-jonze-pete-andre-and-mac.html

Players like Vitas, Henman, Mac, Nasty, Edberg…. you gotta love it.