With special thanks to Mary Carr for the translation

The studies of Matthias Marschik and Helge Faller finally acknowledged the attempts by a generation of passionate female Austrian footballers to introduce into their own country a fully recognised and regulated body for soccer. In addition, the players tried to build a collaborative network in their own countries especially in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, challenging the obstacles that the male world posed, behind an apparent partial collaboration.

In Austria, a first attempt to spread women’s football was carried out between 1923 and 1926. Those passionate about the” beautiful game” sought to collaborate with the players, managers and the press. But male diffidence and prejudice prevailed based on the idea that women shouldn’t get themselves dirty and other anti-aesthetic reasons or because they wanted to preserve and protect women from the rough and tumble world of football, considered at the time to be exclusively masculine and virile. The women’s clubs disbanded, but women continued to be attracted by football, to practice clandestinely or during those few occasions such as matches between the workers’ teams and women in the sphere of theatre, entertainment and music.

A more structured attempt in Austria was led by Edith Klinger, a young woman born on 20th December 1911, into a well-known Viennese family. Marschik and Faller are planning a scientific study about Klinger, this short essay serves as an introduction.

-

Edith Klinger

Illustrierter Kronen Zeitung – 27 February 1935

Klinger took the initiative and on 11th January 1935 she founded with some friends the Erste Wiener Damenfussballclub, later named Tempo. Around this club in a short space of time an underground movement of sport-lovers emerged and eight associations were formed. Kronen Zeitung reported on their interview with Edith’s where she stated that playing football was for her a joy, so it was not only an exciting and intense time for male athletes. Klinger understood that women had to prove they were real athletes well trained and able to sustain an activity to the same level as men. Not only brothers and husbands became involved, instead famous players were called upon to instruct young female footballers in the art of football. Klinger and her friends sought the support of the sports press and found an apparent ally, in Willi Schmieger, the most famous Austrian football journalist of all-time, a beloved radio commentator during the matches of the famous Wunderteam. Schmieger also declared that women had every right to play football as they already played handball, field hockey, raffball, korbball. This statement masked the fact that women had to play shorter times than men, 20 or 25 minutes per time and new regulations were introduced to avoid the anti-aesthetic/anti-hygienic criticisms of the past. At first Klinger and her partner accepted this compromise.

-

Istruttore-e-calciatrici-viennesi – female players and a male instructor

(Klinger beside the instructor on the right)

Illustrierter Krone Zeitung – 27 March 1935,

Illustrierter Kronen Zeitung, more than other newspapers, gave accounts of the matches, the scores and the line-ups, however there was rarely any technical appreciation of the game as such and there was never any real excitement in the commentary of the game as an exciting sporting event, as with handball or field hockey reports. In May 1935 a first of three championships was launched. In March 1936 the women players established their federation the Damenfussball Union.

But Edith Klinger wanted to go further and make greater progress and advances; in April 1935 she became the first female referee in Austria, who had graduated from the Austrian Football Association (ÖFB), with excellent results.

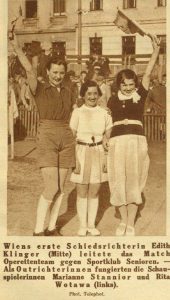

-

Before the match between staff of Operetta and women athletes of Wiener Sportklub.

Klinger is in the middle between the two lineswomen, two actresses Marianne Stannior and Rita Wotawa

Das Interessante Blatt – 23 May 1935

Klinger didn’t only referee games between theatre workers and musicians, but also real men’s games, even though in minor leagues. It was a matter of enormous importance: a woman could direct a male sporting event, sanctioning warnings and imposing football regulations, not likely those imposed on women. Of course, Klinger also aspired for her fellow athletes serious and modern training in proper gyms. She also tried to encourage gymnasts and athletes to become soccer players. Famous athletes such as Dolly Wagner and especially Josefine Lauterbach, the Austrian Olympic representative of the 800m in Amsterdam in 1928 welcomed the call. If women who played football were proven athletes, they could also quickly make up for deficiencies in the control of the ball in football and also make those athletic clashes that men claimed they could not do. Male football had often violent outcomes with injuries, hospitalisations and, for the alleged protection of the female body, they wanted to prevent physical clashes, thereby adjusting the regulations in order to avoid this danger. In studying the experience of the shortened season of Italian women’s football in 1933, Marco Giani emphasised this aspect.

-

Austria vs. Wien

Das Interessante Blatt – 17 October 1935 In the autumn of 1936

ÖFB decided not to officially recognise women’s participation in the sport because no other body in the World did. Unlike the Italian case, in which fascism prohibited such activity, Austro-fascism tolerated the activity, but tried make life difficult for the players by forbidding matches on pitches affiliated to the federation, imposing a disqualification for the members.

-

Caption states that the two Viennese women, Celond and Reinthaler, have founded an Austrian women football club in Guildford, Surrey

Illustrierter Kronen Zeitung – 12 May 1936

Women were able to play in small stadiums, thanks to very minor amateur clubs which were not interested in federal affiliation. The Championship lasted until May 1938, when Nazi Germany had already annexed Austria and in August the regime forbade women’s football.

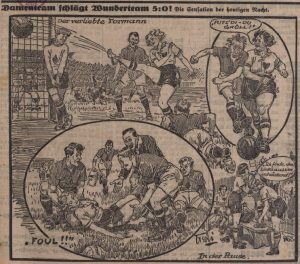

- The cover of issue of Illustrierter Kronen Zeitung of 1st April 1936. Which was full of stereotypes of women. The mocking title was “A women team defeats Wunderteam 5 to 0”

-

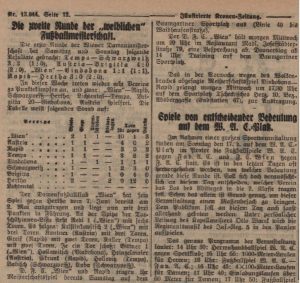

Report with standings of women championships

Illustrierter Kronen Zeitung – 12 May 1936

The worst affected victimwas Edith Klinger, who could claim the distinction of having refereed two international men’s matches: in Brno on 15th November 1935 between SK Brno and Ostmark XI from the second Viennese league, and in Rousinow on 8th September 1937 between the local Czechoslovak team and Austria’s SK Möllersdorf. However, this second match took place after Klinger was prevented in Austria, not only from refereeing men’s but also women’s matches. Klinger’s referee license belonged to the ÖFB, she also obtained another refereeing diploma this time for ice hockey – another rampart in the all-male reserve.

-

The Brno team that played on 18th September against DFC Austria, representing Vienna in an international town match for women footballers

Illustrierter Kronen Zeitung – 25 September 1936

On 5 February 1937 Klinger resigned as vice-president of the Damenfussball Union. Both the qualifications remained useless, because the ÖFB and the ice hockey federation had the power to appoint referees. Another strong-arm tactic was adopted in November when the ÖFB opened the referee course at the Union. In December, the most determined of Klinger’s supporters challenged the ÖFB by announcing an increase in playing time to 45 minutes, the same as men’s matches. But the only referees available were men and they refused, so the times remained at 20 and/or 25 minutes for some time to come.

-

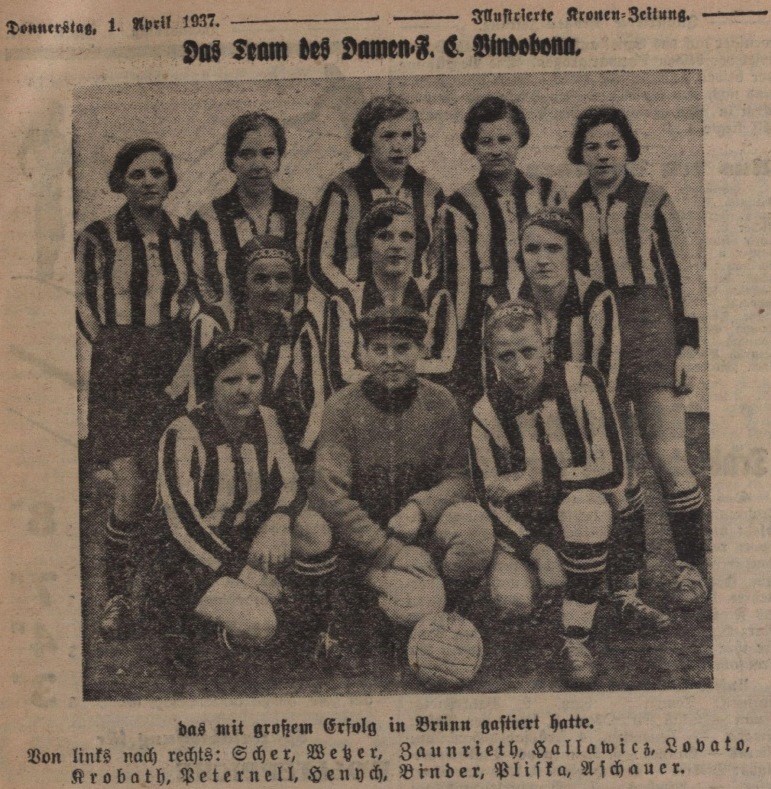

The last photo that Illustrierter Kronen Zeitung dedicated to women football and it sports club Vindobona

Illustrierter Kronen Zeitung – 1 April 1937

Article © Gherardo Bonini

There’s an article dated 1937 or 1938 (sorry I’ve got the microfilm scan and cannot find it now) on the italian sportspaper “La Gazzetta dello Sport” in which political austrian government banned the austrian womens football championships. I don’t think anschluss to be already set in.

Dear Nicola,

Sorry for not having remarkled your instalment until now. You’re right. In October 1936, Austria federation banned women football and Patriotic Front confirmed this decision, notwithstanding opposition of influential Willy Schmieger. Women footballers continued their self-managed activity playing in small pitches of minor clubs not attached to Austrian federation. Police did never stop these matches, at maximum they checked identity papers. Last games took place in May 1938. Nazi government in August 1938 forbade whatever activity. In case of pirate matches, police would have arrested the women players. Thanks again !