Hugh Stuart Fullerton, a Chicago-based newspaper reporter, working in the latter years of the nineteenth and early years of the twentieth centuries, was undoubtedly a pioneer of sport notation; developing a comprehensive ideographic method for assessing baseball. However, for him, the use of statistics to inform future performance was seemingly unimportant; Fullerton viewed his notations as merely transferring the game onto paper. Others though viewed his systematic observations as more important. Elmer Berry, a professor of physiology, and baseball coach, at the International Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) College in Massachusetts, recognised the potential of Fullerton’s work. In the preface of his 1916 book, Baseball Notes for Coaches and Players, Berry states that he is, ‘especially indebted for much of the most valuable material to Mr Hugh S. Fullerton and his articles in The American Magazine’, referring to two articles, The Inside Game published in 1910 and Hitting the Dirt in 1911. It is clear that Berry considered notation data as useful to coaches; however, in his work, Berry falls short by failing to indicate how Fullerton’s data could actually inform coaching practice.

Others were more perceptive, recognising the potential influence of game statistics on performance. Remley, writing in the December 1913 issue of Baseball Magazine, suggested that, ‘reducing an athletic performance to figures adds greatly to the account of the game, throws light upon the reasons for victory and defeat, and furnishes inside information concerning the units which make up the team’. In his article, he presented a ‘system which the writer has used himself for scoring football (gridiron) games’, and argued the need for the development of a ‘scoring system’ similar to that used in baseball, which would enable a comparative analysis of players’ abilities.

Similarly, in an article written for the April 1890 edition of Outing, William Strunk Jr. extoled the virtues of assessing player performance; presenting his idea for notating tennis matches, which he suggested had been tested in a tennis tournament of 1889. He outlined that it was, ‘designed for the recording of tournaments and championship games, with a view to assigning each player a definite rank.’ Strunk’s system was relatively basic, providing simplistic game data; however, apparently unbeknown to Strunk, a more complex system for analysing lawn tennis already existed.

In the Lawn Tennis Manual (1885), in a section entitled ‘Hints for Scoring’, the writer advocates the use of a detailed scoring system, ‘which records the character of every played ball, whether it be a fault, a served ball, a returned ball, a volleyed return, together with the number of ‘exchanges’ of played balls’. These data, he argued, would provide ‘an analysis of a player’s skill’. The notation system presented in this piece is extremely detailed; however, perhaps more startling is the fact that notations of sports performance, specifically designed for analytical purposes, were in existence several decades prior to the publication of this article.

In Beadle’s Dime Base Ball Player (1861) it is stated that ‘in order to obtain an accurate estimate of a player’s skill, an analysis, both of his play at the bat and in the field, should be made, inclusive of the way in which he was put out’. Further to this, it was emphasised that all clubs must score in ‘a uniform manner’ and to assist this, the writer even presented a scoring template (notation system) that would ensure consistency in recording games. The author of this piece, and ‘pioneer’ of sport notation system, was baseball reporter, Henry Chadwick.

- ‘The Father of Baseball’- Henry Chadwick

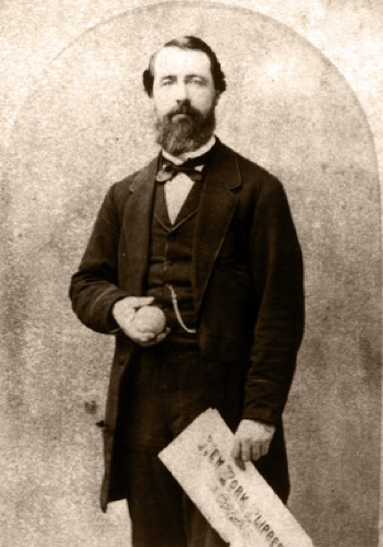

Henry Chadwick was born in Exeter, England, on 5 October 1824 and migrated to the United States in September 1837. From an early age, he exhibited a passion for music, excelling in both piano and guitar. He was a prolific composer and whilst his love of music endured throughout his life, it was not to be his calling; Henry leaned towards a career in journalism, and by the start of the 1850s, he had become a full time sports reporter. Early in his newspaper career, Chadwick recognised the need for an observation system that could be used to analyse the game of baseball. Writing in the 1860 Beadle’s Baseball Dime, and again in the same publication, in 1862, he suggested that every club should have its regularly appointed scorer, who should be one who fully understands every point of the game. In addition, Chadwick outlined, he must be a person of sufficient power of observation to note down correctly the details of every innings of the game. Chadwick, by this time, had devised a complex scoring system, or in reality a notation system, for baseball, which he later argued was ‘a system of short-hand [sic] for movements in scoring a game of baseball’.

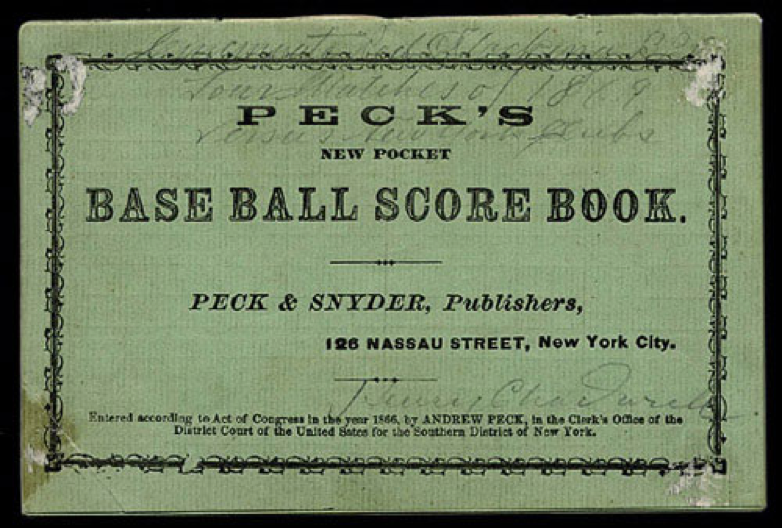

- Chadwick’s own scorebook from 1869

Whilst Chadwick’s system was first published in 1859, there is evidence to suggest that it had been developed, and used, a year earlier. In a letter written by Henry Chadwick, presented in the October 1895 edition of Sporting Life, he discusses his deceased friend, and former baseball player, Harry Wright. He wrote, ‘Harry played his first match in base ball [sic] in July 1858… I have the score of this game, which I reported for the “Clipper” in my earliest score book’. Further to this, he added, ‘I used the same signs, abbreviations and shorthand notes, such as now form, the basis of the scoring method of the present day’.

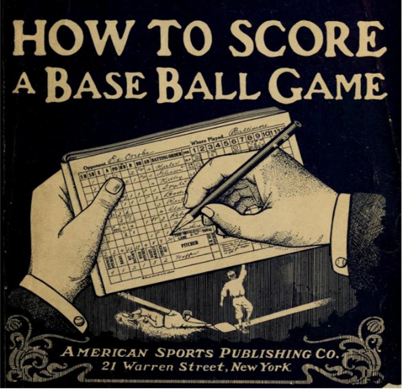

- The Box Score Card

Unlike the later work of Hugh Fullerton, Chadwick’s rationale for the notation, was not merely to record the game, but that it should be used for analysis. Further evidence of the scoring system being used in this context, comes from the same letter, in which he recalls Harry Wright relating to him, that from his first year in management to his last he had adopted Chadwick’s ‘scoring’ method.

Chadwick’s notation system perhaps represents the first attempt to analyse, systematically, athletic performance, and the ‘ghost’ of his system still exists in the baseball scorecards of today. Chadwick’s impact on baseball has been widely acknowledged, but his influence reached far beyond the game he loved; his ‘box scorecard’ would prove to be a template, and catalyst, for the development of notational systems in many other sports, in many parts of the world. Thus, Henry Chadwick’s, sobriquet, ‘The Father of Baseball’, can now be modified to- ‘The Father of Baseball, and Sport Notation’.

Article © Simon Eaves