In March 1927 Cadbury’s acclaimed research chemist Arthur Knapp (1881-1939) took to the stage of the factory’s new Concert Hall. Dressed as Father Time, he told of the wonders of the world he had witnessed to date. Recalling the spectacle of the Pyramids of Egypt, the story-telling of Homer, the falls of Carthage, Rome and Spain, and the theatre of Shakespeare, the kindly patriarch (and Cadbury Senior Manager) concluded that, when he looked back on all of these ‘spacious days of old’:

‘No greater marvel did I e’er behold

Than this – / to find within a Factory’s scope

A stage so set that critics cannot hope

To find a fault. / From now magnificent

Will be your Drama / and more excellent

Your Music!’

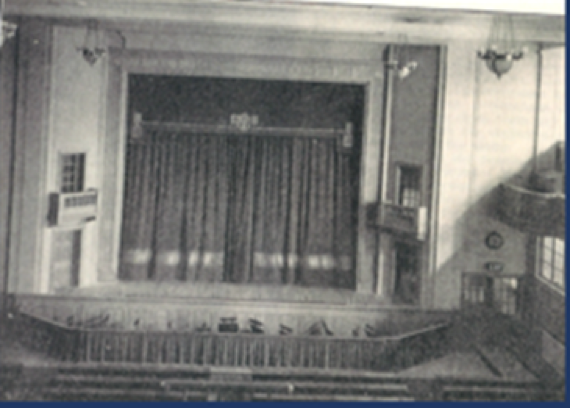

The Concert Hall formed one part of a major building project at Cadbury’s Bournville site. Production efficiencies required by the challenging post-war economic landscape had prompted shifts in thinking about business operations at Cadbury. Many of the site’s earlier Victorian factory buildings were demolished during the 1920s and replaced with newly constructed spaces capable of accommodating the machinery needed to produce cocoa and chocolate on a mass scale. The Concert Hall sat within a new, four storey Dining Block. Catering for between five and six thousand staff each day, this large building offered a range of services that far exceeded eating, including dental surgeries, a library, reading room, club rooms and lecture room. The Concert Hall was on the ground floor, and with a capacity of one thousand and fifty, an under-stage scenery store, good lighting technology, dressing rooms and an orchestra pit it marked a step change in theatrical production and entertainment at Cadbury. As Father Time claimed, ‘from now magnificent will be your Drama, and more excellent Your Music’.

- Courtesy of Cadbury Archives and Heritage Services

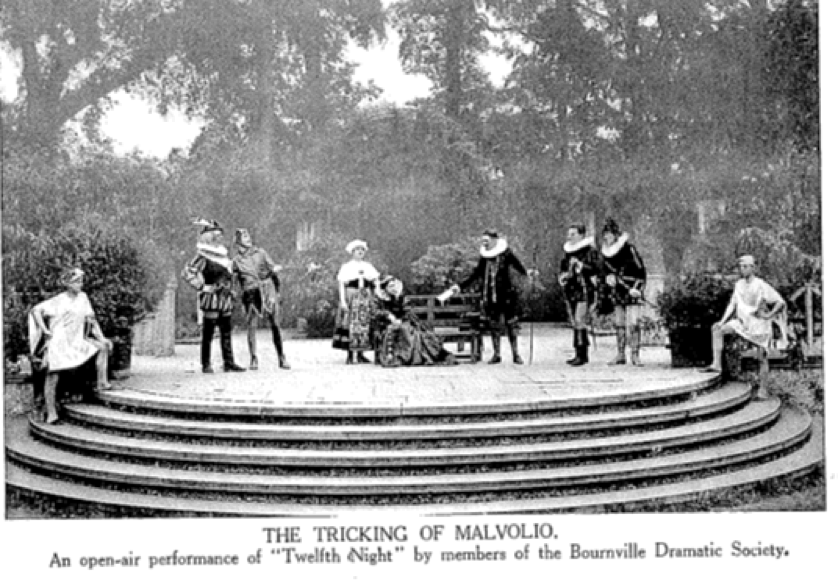

A sense of the significance of this new, modern performance space to Cadbury’s management and workers can be gleaned from the week of celebrations that marked its opening. Six evening performances were offered by staff performers; programmed by a small committee of representatives from the recreational societies that contributed. The Cadbury family were Quakers and it would be easy to assume that the Quaker condemnation of theatrical activity that was particularly dominant during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries might have restricted involvement in theatre at Bournville. By the second decade of the twentieth century this was not the case. The Bournville Dramatic Society had been established in 1916 and the Cocoa Works were well-known in Birmingham, and further afield, for the staging of large-scale, outdoor pastoral pageants. More recently theatre had been celebrated in ‘Drama and the Worker’, a chapter published in the 1921 Cadbury’s souvenir publication Bournville: A Review and featured in the company’s education programmes as both subject of study and a way of teaching.

April 1927’s edition of The Bournville Works Magazine dedicated six pages to the Concert Hall’s opening week. It reports that audiences were made up of a mix of company directors, factory employees and their families and that the numbers were ‘very large’ throughout the week, meaning that ‘on two or three occasions late comers were unable to get in’ (REFERENCE). Considering these reports of sell-out evenings and detailed lists of people involved in the performances it seems likely that somewhere between six and half and seven thousand people engaged with the opening week of events – as either participants or spectators / or both. As more mechanised production lines were introduced this was an important way to affirm the significance of human employees to Cadbury.

- Courtesy of Cadbury Archives and Heritage Services

The week’s entertainments were a mixture of music, theatre and dance. Sunday, the opening night, saw Bournville Dramatic Society present a triple bill; reviving plays they had performed before, in part at least, because the late-running building project meant there had been no time for rehearsal in the space. The programme entry for Monday’s Youth Club entertainment makes no mention of theatrical performance, but other reports make it clear that it included The Gods of the Mountain, a short play praised for its beautiful spectacle – largely the result of the costumes that had been designed by the Factory’s design office, a group more ordinarily tasked with designing posters and packaging. Thursday’s variety-based entertainment included two dance performances. The Bournville Centre of the English Folk Dance Society transported the audience back in time ‘to the Merrie England of village green and maypole’. Following that was a fairy ballet performed to Grieg’s Peer Gynt suite by Bournville Girls’ Athletics Club – choreographed by Miss Forbes, a member of the company’s Gym staff.

Cadbury offered a range of in-house entertainment production and theatrical spectatorship and participation was actively encouraged. This encouragement increased during the 1920s as the established belief in the personal benefits of creative recreational activities that can be traced back to the mid-Victorian period regained momentum post war. The 1920s also marked a period in which the economic benefits of worker well-being and happiness were widely and explicitly articulated for the first time. An understanding that there was a connection between creative recreational activities and the commercial benefits of such activities was a topic that was evaded and, indeed, denied in the pre-War industrial world. The 1920s marked a turnaround in relation to this: in 1929 the in-house magazine published by Fry’s (a company part-owned by Cadbury by this time) published an article entitled ‘Happiness in Industry’ in which the author drew a direct connection between the happiness of employees and profit. ‘The best brains in Industry to-day’, s/he writes, ‘are realising that the happy and whole-hearted co-operation of its employees is the finest asset any firm can possess […] money spent in securing it is money invested in a gilt-edged security for the share-holders’ benefit’. The opening of the Concert Hall ‘within a Factory’s scope’ and the enthusiasm for staff performances sit within this well-established, progressive business model. At Bournville recreational theatre, music and dance served staff and business interests well.

Article © Catherine Hindson