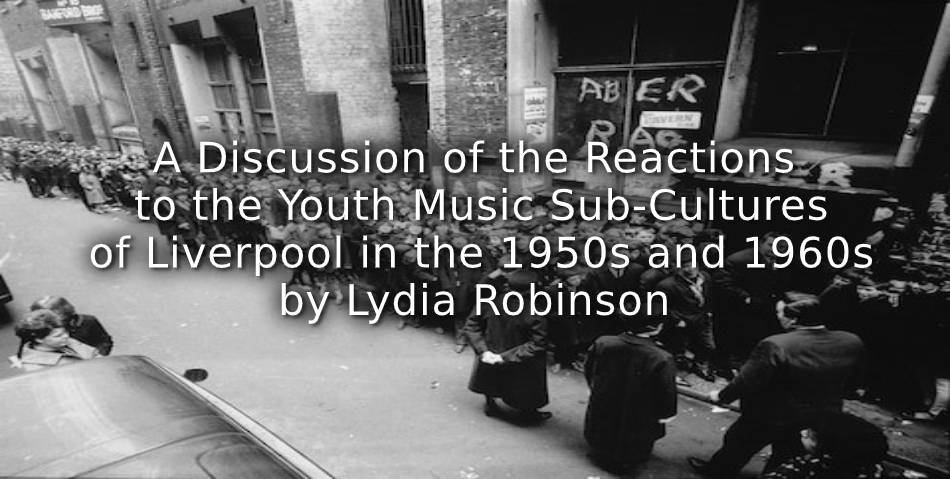

When we were given the chance to research any area of leisure history, I decided to choose this topic due to my ongoing interest in the story of The Beatles. Having attended a number of annual International Beatle Weeks in Liverpool, listening to speakers who knew or worked with the band, I saw this topic as an opportunity to explore the social context in which The Beatles emerged. As they were highly favoured by young adults and teenagers, I decided to focus my research on the changing British youth music sub-cultures from the 1950s to the 1960s, and the responses from the older generation that followed. With this in mind, I wanted to focus particularly on Liverpool, as it was the epi-centre of changing youth sub-cultures and home to The Beatles.

To truly comprehend the rise of youth sub-cultures in Britain, the context in which the image of British teenagers and their place in society changed, must first be understood. The start of this change can be seen at the end of the Second World War. Britain was truly transformed by the end of the war, not only economically, but socially too. The working-class youth demographic was earning a steady wage once they left secondary school. They were financially doing quite well, and have been suggested by historians to be an ‘untapped consumer group,’ by the early 1950s.[1] This new financial independence helped establish the first time young adults were called ‘teenagers’, and British teens were notably more financially stable than those in other European countries.[2] Due to their new disposable income, teenagers began spending their money in popular hotspots for socialising, such as music venues and youth clubs.[3] Going out with friends to the local music hall to dance became a common pastime. However, with the start of this freedom, came a response of fear from those in authority. There was notable worry surrounding what the youths were doing with their free time, what they spent their money on, and the negative effects this may have on their morality.[4] The term used for this fear is ‘moral panic’.[5] When looking at Liverpool, the response of moral panic can certainly be found. It is seen in the introduction of rock and roll, and then subsequently, the popularity of the Beatles.

1955: Teddy Boys on a night out in London

Source: https://www.standard.co.uk/lifestyle/london-life/19-vintage-pictures-of-dapper-london-teddy-boys-a3258626.html

Described by Robert Palmer as a ‘generational upheaval’, the American import of rock and roll in the 1950s created a new youth sub-culture in Britain.[6] The ‘Teddy Boy’ was the first well-established post-war youth sub-culture.[7] Their style was based upon the past Edwardian style of dress, with sideburns and tight fitted suits, and they predominantly listened to rock and roll. This new group certainly caused a stir in Liverpool, and the name of the ‘Teddy Boy’ in the media came to be associated with teenagers who were part of criminal gangs.[8] This is part of the moral panic that was felt as a response to the new wave of rock and roll, which was seen as a catalyst for immoral behaviour.[9] In the Liverpool Echo, January 1960, an article on a youth prison describes the inmates as ’the vicious teddy boys…the youths to whom violence has become second nature’.[10] This shows how the teddy boys were represented in the Liverpool media, where they were associated with acts of hooliganism and criminality. In another extract from the Liverpool Echo in 1955, ‘The Mind of a Teddy Boy’, where a London social worker attempts to give the reader a glimpse into their minds, these teenagers were depicted as being violent and completely unwilling to follow any authority.[11] It was likely that many parents would have hated the idea of their son or daughter being associated with these immoral teddy boys.

’The Mind of A Teddy Boy’,

Source: Liverpool Echo, June 1st 1955, p.6, Findmypast Newspaper Archive.

The popularity of the teddy boy image started to fade once the 1960s began. In its place, the frenzy surrounding four local boys outlined the next subculture to enshrine Liverpool. Due to their Liverpool roots, Merseyside was the home of the Beatles. The venues where they regularly played, previous to their sky rocketing fame, such as The Cavern, became holy grail places for young teens to attend.[12] However, similar to the backlash faced by the teddy boys, The Beatles and the vastly popular music venue scene, was seen as a gateway for youths to become involved in morally damaging behaviour. One example of the moral panic, is seen in a Times article, from 1964.[13] It states that teenagers in Liverpool were struggling to secure jobs, as employers were disregarding their ability, due to their Beatles inspired hair.[14] This shows that the negative connotations surrounding Beatle-mania were influencing employers to question a teens character and ability, and subsequently deny them of a job they may have been more than capable at.

Queues outside the original Cavern Club in the Sixties

Source: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/united-kingdom/articles/cavern-club-and-other-iconic-uk-music-venues

‘Beatles Haircut Loses Youth Jobs’

The Times, December 29th 1964, p.4,

Source: The Times Digital Archive, <https://link.gale. com/apps/doc/CS69035933/GDCS?u=chesterc&sid=GDCS&xid=49cadd3e

It is clear to see that, throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the ever-evolving youth sub-cultures were viewed with suspicion and mistrust by the older generations. It can also be noted that even in Liverpool, where the music scene was growing immensely popular, the teenage population was greatly scrutinised for their interests. This was due to the continuing stigma surrounding the new sub-cultures of music, which was largely a consequence of the media’s influence.

Article © Lydia Robinson

References

[1] R. Palmer, ‘The 50s: A Decade of Music That Changed the World’, Rolling Stone, <https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/the-50s-a-decade-of-music-that-changed-the-world-229924/> [Accessed 17th May 2020].

[2] S. Todd, and H. Young, ‘Baby-Boomers to ‘Beanstalkers’ Making the Modern Teenager in Post-War Britain’, Cultural and Social History, 9.3 (2012), 451-467, <https://doi.org/10.2752/147800412X13347542916747>.

[3] S. Todd, and H. Young, ‘Baby-Boomers to ‘Beanstalkers’ Making the Modern Teenager in Post-War Britain’, Cultural and Social History, 9.3 (2012), 451-467, <https://doi.org/10.2752/147800412X13347542916747>.

[4] J. Garland and others, ‘Youth Culture, Popular Music and the End of ‘Consensus’ in Post-War Britain’, Contemporary British History, 26.3 (2012), 265-271, <https://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2012.703002>.

[5] J. Garland and others, ‘Youth Culture, Popular Music and the End of ‘Consensus’ in Post-War Britain’, Contemporary British History, 26.3 (2012), 265-271, <https://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2012.703002>.

[6] R. Palmer, ‘The 50s: A Decade of Music That Changed the World’, Rolling Stone, <https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/the-50s-a-decade-of-music-that-changed-the-world-229924/> [Accessed 17th May 2020].

[7] R. Staveley-Wadham, ‘Hooligans and Gangsters? A Look at the Teddy Boys of the 1950s’, British Newspaper Archive, April 7th 2020, <https://blog.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/2020/04/07/a-look-at-the-teddy-boys-of-the-1950s/> [Accessed 18th May 2020].

[8] ‘Report calls for special “street walkers” to engage with gangs of troublesome youth’, Guardian, 21st February 1961, <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/feb/21/how-to-deal-with-teddy-boys-and-girls-archive-1961> [Accessed 18th May 2020].

[9] G. Mitchell, ‘From “Rock” to “Beat”: Towards a Reappraisal of British Popular Music, 1958–1962’, Popular Music and Society, 36.2 (2013), 194-215, <https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2012.681546>.

[10] ‘Prison Within a Prison’, Liverpool Echo, January 19th 1960, p.6, Findmypast Newspaper Archive.

[11] ’The Mind of a Teddy Boy’, Liverpool Echo, June 1st 1955, p.6, Findmypast Newspaper Archive.

[12] M. Brocken, Other Voices: Hidden Histories of Liverpool’s Popular Music Scenes, 1930s-1970s, (London: Routledge, 2010), <https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=lRQ3DAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb#v=onepage&q&f=false> [Accessed 17th May 2020].

[13] Beatles Haircut Loses Youth Jobs’, The Times, December 29th 1964, p.4, The Times Digital Archive, <https://link.gale. com/apps/doc/CS69035933/GDCS?u=chesterc&sid=GDCS&xid=49cadd3e> [Accessed 15th May 2020].

[14] Beatles Haircut Loses Youth Jobs’, The Times, December 29th 1964, p.4, The Times Digital Archive, <https://link.gale. com/apps/doc/CS69035933/GDCS?u=chesterc&sid=GDCS&xid=49cadd3e> [Accessed 15th May 2020].