To read Part 1 of this series please click HERE , Part 2 Click HERE , Part 3 HERE and Part 4 HERE

The fifth and final article in the Northern School of Music series takes us into the battlefield of music education politics in post-war Manchester. The outcome of which was the Royal Northern College of Music from nearly 20 years of negotiations. So how does the story go?

A miscalculation

In 1955 the local authorities who paid grants to the Northern School of Music and to the Royal Manchester College of Music (further up Oxford Rd), had a look at their finances. They noticed that they were paying out annual sums to two music schools who were literally just up the road from each other. In their view, this was an opportunity to streamline spending.

Why doesn’t one just merge into the other and then they only have to pay a single school, and support single building?

Because, said both schools, we are completely different organisations and it’s a terrible idea.

They were correct, of course. The Royal Manchester College of Music’s activities were dedicated almost solely to the production of music performers ever since its founding in 1893 by Sir Charles Hallé. The Northern School of Music, as we know, had an emphasis on training music teachers. One simply couldn’t blend into the other and still deliver the same service.

Desperate for change

Both schools were, however, in need of a change. Especially a financial change. The Northern School was losing more money than it was granted and the Royal Manchester was in dire need of new premises, its being heavily damaged in the Manchester Blitz.

The councils pressed the point. Taxpayers should have their investments spent on improving music education in a way that does not double the cost of paying for buildings, insurance and rates etc.

So, the conversation was opened again a few years later. A straightforward merge was off the table, but the Northern School offered that it would be interested in a brand-new initiative if one could be designed that incorporated the mission of both schools.

Thus, the idea for a new college of music came to being. The two schools would dissolve and funnel their assets. students and some staff into the new endeavour, giving it a head start.

1963 was given as the goal for the grand opening, with a total cost of about £300k. Little did they know at the time, but it was to take another decade and few more hundred grand for a new building to open its doors.

A digging of heels

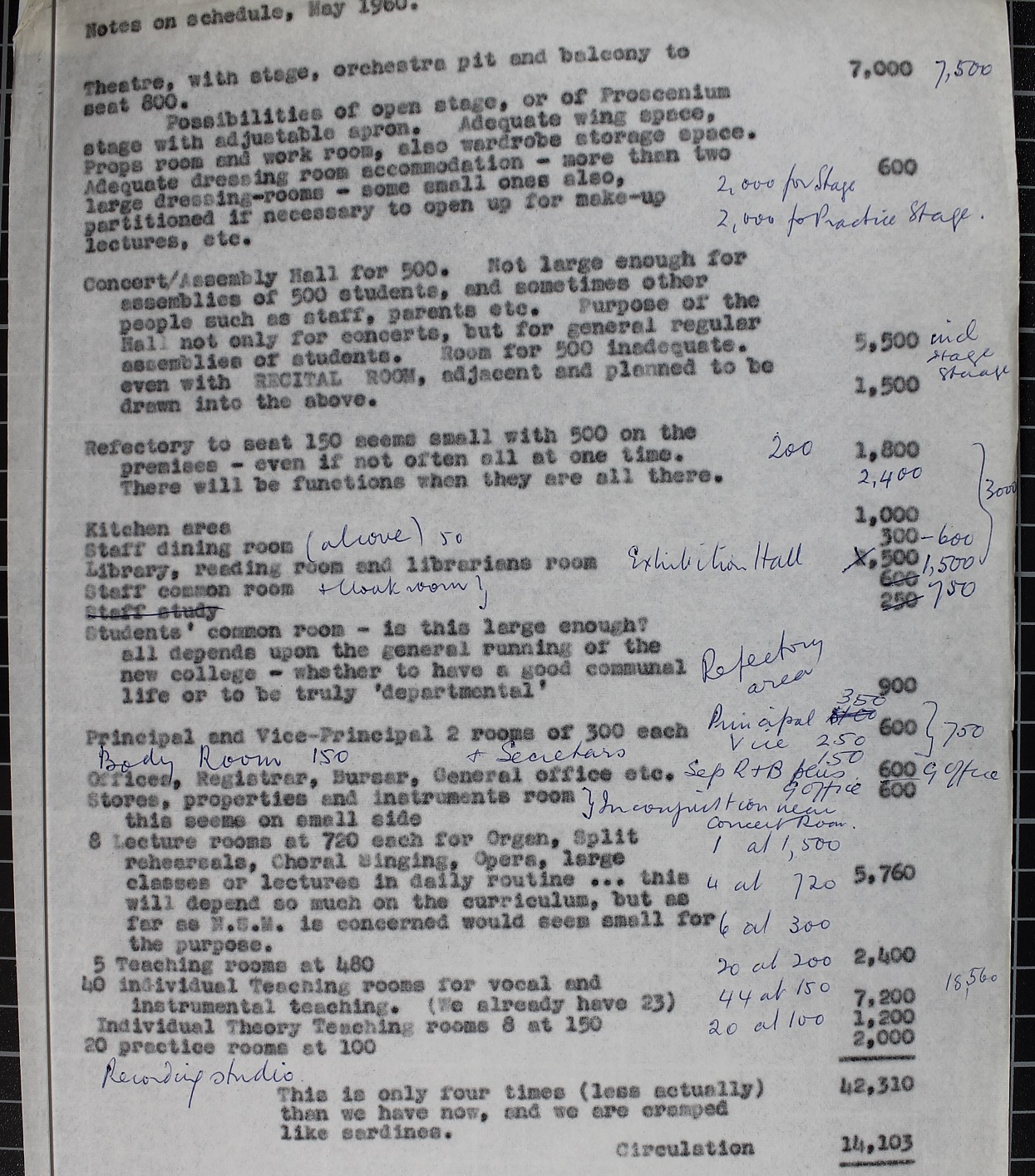

The angry scribbles on the Joint Committee meeting notes scratched in by Ida Carroll tell a very interesting story. Both schools were required to list what staff they had, the number of students, the amount of space and assets they have and much more. From these notes, specifications for the new school’s activities and resources would be drafted up.

The initial results were pretty insulting apparently.

Not only were basic needs like a big enough teaching spaces lacking in sufficiency (or windows, to the students’ horror), but the outlines of the new college seemed to totally ignore a huge chunk of what made the Northern School of Music so successful. Overall student capacity was less than that of the two schools put together, there was no provision for a Junior School, part-time students were not accommodated and there was no mention of the Speech and Drama Course. Ida’s tenacity headed up the charge and she fought tooth and nail at every instance to ensure the school’s efforts over five decades of education were not lost in this new initiative.

The Royal Northern College of Music now has capacity for nearly 900 students, the Junior School survived to this day, the Speech and Drama Course was absorbed by Manchester Metropolitan University and the Old Students Association persevered to become RNCM Alumni. The only reason for this, is Ida Carroll’s determination that the passionate efforts of the school would not be dismissed in the changing landscape of Manchester’s music offering.

-

Ida’s notes

Ida Carroll almost tears apart the early plans for the new college’s facilities

Swinging ‘60s? Not so much

Alongside these conversations, there were endless delays throughout the 1960s. The Royal Manchester College of Music refused to release the totality of its assets to pay for the new college. It required (quite rightly) to retain some liquidated funds to support scholarships for the new school instead of pouring everything into the building itself. In retaliation, the council refused to sign the compulsory land purchase order which would give a building site to the new college, between All Saints Park and the university precinct. The Royal Manchester held out for months, until a reluctant compromise was proposed by the council which allowed the Royal Manchester some control over its assets.

It didn’t seem to matter anyway as government-imposed restrictions on spending, came into play shortly after and the new college was missed off the 1968-9 building programme. The cost had already been upped to over half a million.

Debates in the city about musical life raged in the newspapers. More music teachers were needed to the point where the local council was advertising for them with added financial incentives. The capacity for a permanent opera company and proper dedicated music and arts culture venue was making the rounds again, to very little impact. Part of the Northern School’s building was eventually demolished to make space for the Mancunian Way. It would have been a difficult period for the schools even without the heated negotiations.

However, once it was clear that the new college would not be built in the 1960s, the Northern School of Music celebrated its golden jubilee in 1970 with concerts, services in St Ann’s Church, a school lunch at the Midland Hotel, and even a dinner for the Old Students Association at the Grand Hotel.

In the same year, the unique engraved Perspex window was designed by Alan Boyson and installed at St Ann’s Church, dedicated to the memory of Hilda Collens. A celebration of the impact she had on musical life and training in the North as well as a bittersweet farewell her Northern School of Music.

Northern College of Music

Before gaining royal charter, the new college was established as the Northern College of Music. ‘Northern’ nodding to the Northern School of Music and ‘College’ gesturing to the Royal Manchester College of Music.

What was clear as crystal was that as a new vessel, it must be steered by a brand-new captain. John Manduell, Head of Music for BBC Midlands and Director of Music at Lancaster University, was picked as the principal.

Unbiased towards either predecessor, his focus was solely on developing the new college into a service for music education and performance. The legacies of the old schools came in the form of inherited staff and a foundation stone inscribed by the two school principals Ida Carroll and Frederick Cox. His vision was to create a college that served the cultural needs of the city, as well as the training needs of the music profession. Disappointingly for the memory of Hilda Collens and Ida Carroll, teacher training ultimately was not within this vision.

Surprising no one at the point, there were further building delays. While students were in class for September 1972, the actual building (now costing upwards of £1m) wasn’t ready until 1973. While operating as the Northern College of Music, the Northern School and Royal Manchester continued to teach their own students in their own buildings all the way through the first term.

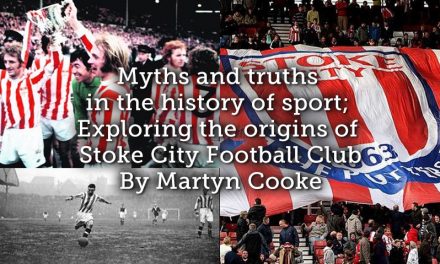

Ida and John

Ida Carroll (left) and John Manduell (next) at the Northern School of Music’s final graduation ball 1972

A 2020 Legacy

So yes, the Northern School of Music is no more. A century from its founding year, however, sees strong threads in Manchester’s music culture and heritage, if you know where to look. The only reason there is the RNCM Juniors is because of the school’s understanding that to get good adult players, you need to provide unique opportunities for young people first. The acknowledgement that alumni are an invaluable resource for current students and school support was championed by the school decades before RNCM Alumni came to being.

The RNCM is even slowly reintroducing musical pedagogy into its syllabus, having dismissed what the Northern School of Music knew long ago: to advance music education, you need to invest in creating good music educators.

The story continues

Whilst this is the final article in the Northern School of Music series for Playing Pasts, we know there are many more stories to be told about the school.

Thanks to the National Lottery Heritage Fund for their unfailing support in allowing us to share these stories.

To learn more about the archive, head over to the website https://www.rncm.ac.uk/research/resources/archives/

For hundreds of digitised images from the Northern School of Music’s various collections, visit our friends at Manchester Digital Music Archive https://www.mdmarchive.co.uk/exhibition/688/a-2020-legacy:-the-centenary-of-the-northern-school-of-music

For a sneak peek at more of the history of the school, discover some key dates on the timeline here https://my.visme.co/view/pvge1n44-nsm2020-2

Article © of Heather Roberts