Playing Past is delighted to be publishing on Open Access – Sport and Leisure on the Eve of World War One, [ISBN 978-1-910029-15-2] – This eclectic collection of papers has its origins in a symposium hosted by Manchester Metropolitan University’s Sport and Leisure History research team on the Crewe campus between 27 and 28 June 2014. Contributors came from many different backgrounds and included European as well as UK academics with the topics addressed covering leisure as well as sport.

Please cite this article as:

Adams, Iain. Did ‘Old Bill’ watch Football? Bruce Bairnsfather and the Christmas Truce, In Day, D. (ed), Sport and Leisure on the Eve of World War One (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2016), 22-46.

2

______________________________________________________________

Did ‘Old Bill’ Watch Football? Bruce Bairnsfather and the Christmas Truce.

Iain Adams

____________________________________________________________

Abstract

One of the micro-level ‘myths’ of Britain’s collective memory of the First World War is of the football match on Christmas Day 1914 between British and German troops. While research has shown that it is improbable that a ‘proper’ match occurred it is highly likely that there were numerous incidents of soldiers playing football. This article examines the evidence of football being played by the Royal Warwickshire Regiment and their opponents at Christmas 1914 and the possible involvement of the cartoonist Bruce Bairnsfather. His description of the truce led to the ‘Khaki Chums’, a group dedicated to understanding the life of the British soldier, commemorating the truce by spending four days in 1999 in trenches as close to Bairnsfather’s experience as possible. When they left, a large wooden cross was set up as a mark of respect for those who fought and died in the area. The local people have adopted the cross and it is regularly treated with preservative and has been set in a concrete base. Today this cross is nearly always surrounded by footballs apart from around Remembrance Day when they are carefully cleared away to be replaced with wreaths and small wooden Royal British Legion crosses.

Keywords: Christmas Truce; Bruce Bairnsfather; Royal Warwickshire Regiment; Royal Saxon Regiment; Football.

Introduction

Captain Bruce Bairnsfather is best known as ‘without doubt, the finest cartoonist of the Great War’.[1] His work, often featuring the character ‘Old Bill’ an elderly pipe-smoking Tommy with a walrus moustache, was considered a major morale booster for British and allied troops. Canadian First World War veteran and cartoonist Bill Mauldin recollected that ‘he was like part of the rations, he became an essential part of our rations like our rum, we decorated our dugouts with his cartoons’.[2] Mark Marsay, compiler and editor of the The Bairnsfather Omnibus editions, recalled his grandfather, a Military Medal winner at The Somme, always spoke of Bairnsfather ‘with a broad grin and acknowledged that he was one of those rare few of the “officer class” who knew what it was really like, day by day, for himself and his pals in the trenches’.[3]

Bairnsfather had joined the army in 1906 and was initially assigned to the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. However, he left the army in 1908, chiefly because of boredom, and enrolled at John Hassell’s New Art School and School of Poster Design in Kensington. At the outbreak of war he re-joined the army and was commissioned as a Lieutenant in his old regiment and assigned, as machine-gun officer, to the 1 Battalion (1/R. Warwick’s) in November.[4]According to Robert Hamilton, a captain in the battalion, Bairnsfather arrived at the front on 20 November when the battalion was preparing to leave their billets at Brasserie L’ Espérance in Pont de Nieppe after a week’s rest.[5] They were to assume responsibility for a dog leg line of trenches to the north and north-east of Ploegsteert Woods, relieving the 2 Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers (2/R. Dublin Fus.).[6]

The trenches

By mid-November, Erich von Falkenhayn, the German Chief of Staff, realized that continuing the traditional Prussian strategy of bewegungskrieg, a war of movement, would probably lose the war. He advised the Kaiser to sue for peace from the favourable position of occupying valuable tranches of France and Belgium, but this was rejected and von Falkenhayn was forced into the protracted operations of siege warfare.[7] He ordered the construction of defensive lines, in depth, from the English Channel to the Swiss border, over about 720 kilometres. The allies built parallel trench lines, although not to the same quality as they intended to carry out an offensive strategy to recapture the ten German occupied departments of France and the Belgian channel ports.[8] General Joseph Joffre, the commander-in-chief of the French Army, refused to abandon the initiative and thought that defensive warfare destroyed morale; ‘let us attack and attack…no peace or rest for the enemy’.[9] In the autumn and winter of 1914-1915, the British held a section of about forty kilometres from just south of Ypres to Givenchy.

No man’s land averaged between 90 and 360 metres in width, although in places it was less than five metres and in others over 900 metres; Bairnsfather estimated no man’s land was about 180 metres wide in front of the 1/R. Warwick’s over Christmas 1914.[10] The stress of continuously being under fire quickly forced the adversaries to set up troop rotation systems; the British being typically three to five days in the firing trenches, and then the same in both the support trenches and reserve trenches before enjoying a week in billets.[11] However, between 22 November and into the New Year the 1/Royal Warwick’s and the 2/R. Dublin Fus. were alternating in the lines every four or five days.[12] The Ploegsteert section was comparatively ‘hot’ when the Warwick’s entered for the first time. In the Warwick’s War Diary ‘incessant sniping all day’ is noted on both the 23 and 24 November with two killed and two wounded on the 23; three wounded on the 24, and ‘8 casualties, all sniped’ on the 25 November.[13] Lt. Black, one of Captain Hamilton’s subalterns, in a letter of 2 December 1914, wrote:

The position we are holding now…is a very warm corner; shots are flying up the trenches & across them all day long, & most of the night…my servant was wounded last time we were up here.[14]

Bairnsfather’s initiation into the trenches closely followed the onset of winter weather and he noted ‘it was a long and weary night, that first night of mine in the trenches. Everything was strange and wet and horrid…many of the dugouts had fallen in and floated off downstream’.[15] On 6 December the War Diary reported ‘rain in afternoon. Heavy rain all night’ and then on 7 December ‘very heavy rain in morning & all day’. By 8 December, the ‘trenches awful. Rain most of night. Tried to drain trenches but found it useless’ and on 9 December ‘trenches in a very bad state. Work all night – trying to make them habitable, 2 killed, 8 wounded’ and then on 10 December ‘conditions as bad as possible’.[16]

In December 1914, more rain fell than in any December since 1876, over 15 centimetres, causing Private Tapp, an officer’s servant in the Warwick’s, to write ‘it will take boats to relieve us’.[17] Bairnsfather drew a cartoon of two privates in a trench standing up to their chests in water titled ‘The New Submarine Danger’; one says ‘They’ll be torpedoin’ us if we stick ‘ere much longer, Bill’.[18] Captain Hamilton revealed that the conditions were beginning to develop some professional empathy between the British soldiers and their opponents noting ‘poor British Tommy, but one and all declared that if the Germans could stand it, surely they could’.[19]

Live and let live

The closeness of the enemies enabled them to see beyond the propaganda to the humanity of the opposition; they recognized experiences and problems in common. Sondhaus points out that, paradoxically in such a violent and bitter war, ordinary soldiers swiftly adopted informal live-and-let-live arrangements wherever the lines stabilized with the men carrying out shouted conversations and choral singing with their enemies.[20] Tapp noted that in one tour of the trenches, the Germans and British were putting up targets for each other to aim at and were signalling hits and misses.[21] Where the trenches were particularly close newspapers and other goods were thrown across; these tacit truces made life less exhausting and dangerous for both sides although actual fraternization was rare.[22]

The soldiers on both sides recognized that the weather was making the movement of troops and heavy equipment difficult, which combined with the significant losses of troops, pack animals and matériel during the first three months of the war, made meaningful offensives unlikely before the spring.[23] One reason why the officers, on both sides, were keen ‘to prevent the enemy seeing our trench system’ was to keep hidden how badly they were equipped and manned.[24]

The approach of Christmas

Rumours of fraternization and live-and-let-live attitudes reached the press and began being reported in the newspapers.[25] International figures such as Pope Benedict XV and Senator William S. Kenyon attempted to broker a truce for the proper celebration of Christmas.[26] The High Command on both sides recognized the probability of increased fraternization and took measures to enforce an aggressive attitude and encourage vigilance. The French believed the Germans were withdrawing troops to the Eastern front and decided upon offensive operations to break through the entrenched defensive line. The British supported these moves and a number of small, but costly, attacks were ordered between 14 and 19 December. These included a tactical attack on 19 December to straighten the lines to the immediate right of the 1/R. Warwick’s and they were ordered ‘to assist the attack by enfilade fire against enemy in front of the 11th Inf Brig and by rifle and M.G. fire on enemy’s trenches opposite theirs’.[27] Bairnsfather, as machine gun officer, set up one of his guns to enfilade a support trench and during the attack:

I caught sight of a lot of the enemy running along a shallow communications trench of theirs, apparently with the intention of reinforcing their front line. We soon had our machine gun peppering up these unfortunates, and from that moment on kept up an incessant fire on the enemy.[28]

These attacks accomplished little and heavy casualties occurred leaving numerous dead in no man’s land.[29] After the battle, the 1/R. Warwick’s were relieved by the 2/R. Dublin Fus.’s on the evening of 20 December, most of the Warwickshire casualties having been caused by British artillery rounds falling short and wide of their target.[30] Bairnsfather noted that:

A few days later, as I happened to be passing through poor shattered Plugstreet Wood, I came across a clearance amongst the trees. Two rows of long, brown mounds of earth, each surmounted by a rough, simple cross, was all that was inside the clearing. I stopped, and looked, and thought – then went away.[31] (Figure 1)

Figure 1

Ploegsteert Wood Military Cemetery contains two rows of Shropshire Light Infantry graves from 19 December 1914

Photograph by the author, March 2014.

Christmas Eve

After a very short break, they returned to the same trenches on the evening of Christmas Eve to relieve the Dubliners.[32] During the day they had received a message from General Headquarters that ‘the enemy may be contemplating an attack during Xmas or New Year…special vigilance will be maintained during these periods’.[33] A similar message was issued by German High Command to their forces regarding allied plans.[34]The Germans had been supplied with Christmas trees and candles allowing them to follow the German tradition of singing and drinking around the tree. In many places these trees were placed on the trench parapets, with the candles lit, initially causing concern to some allied troops opposite who thought some new dastardly deed was afoot.[35]

Leutnant Kurt Zehmisch left his billet at 6.00 p.m., 5.00 p.m. British time, with his regiment, the 134 Royal Saxon Regiment (134/Saxons), for the trenches opposite St Yves, facing the 1/R. Warwick’s. He had ordered his men, the 11 Company, not to fire when they got into the lines that evening or on Christmas Day except in defence.[36] Tapp was relieved by the lack of shooting as they approached the trenches through Ploegsteert Wood to replace the Dubliners and soon they heard the Germans singing. Tapp’s officer, Lt. Tillyer, ordered his company to sing in turn which they did with gusto.[37] Captain Hamilton had been told by the departing 2/R. Dublin Fus. that the Germans wanted to talk and as they settled down the Germans began shouting across ‘Are you the Warwick’s?’. The men replied ‘Come and see’, eliciting a German response of ‘you come half way, and we will come half way, and bring you some cigars’. After considerably more banter, Hamilton’s former servant, Private Gregory went out and came back with cigars and relayed they wanted to meet an officer.[38] Black wrote to a friend on the 31 December that:

On Christmas Eve, one of our men went out unarmed & met two Germans half-way between our trenches, & amid cheers from both lines they lit each other’s cigarettes; the Germans promised not to fire till boxing-day unless we did, & if they received orders to fire, they would fire high to warn us. That evening we were strolling about outside the trenches as though there was no war going on.[39]

After more shouting, it was agreed that Hamilton would meet a German officer in no man’s land at dawn, unarmed.[40]

Further to the north-west in the 1/R. Warwick’s lines, Bairnsfather noted that there had been no shelling in the area during the day and in the evening he enjoyed a dinner in a dugout at the far northern end of their trenches, a bottle of red wine and tinned goods sent from home making a pleasant change from bully beef. On returning to the trench section in front of his dugout he found the men in good spirits, singing and joking. Opposite, Zehmisch certainly wanted to converse and started whistling to attract the attention of the British. His company rapidly joined in the whistling and they soon heard discordant responses. Zehmisch, assisted by Private Möckel who had lived in Britain for years, then started shouting suggestions to meet and exchange German cigars and English cigarettes. Möckel and Private Huss volunteered to venture into no man’s land if the British agreed. Upon approval by the local platoon commander, Bairnsfather and his machine-gun section sergeant, Rea, went along a ditch extending into no man’s land to a hedge to get closer. Their shapes must have shown as the Germans challenged there being two of them, so Rea continued alone with his cap full of cigarettes and tobacco. He met two Germans and the men of ‘C’ Company could hear the muffled conversation. As they parted Rea shouted a ‘Merry Christmas’ and ‘Happy New Year’ to the Saxon trenches and Zehmisch replied to the Warwickshire trenches. Rea returned to cheers with a haul of cigars and a cease fire agreement for Christmas Day.[41] Tapp reported:

One of the Ger’s who can speak Eng is shouting over to us to go over, we shout back “Come halfway”. It is agreed on, our sergeant goes out their man takes a lot of coaxing but comes at the finish and we find they have sent two we can hear them talking quite plain they exchange cigarettes and the German shouts to us a Merry Xmas we wait the Sergeants return, he gets back and tells us they are not going to fire tonight if we don’t, they have got lights all along their trench and also a Xmas tree lit up they are singing so we give them one, it is funny to hear us talk to one another.[42]

In the dark of Christmas Eve, the 134/Saxons and Warwick’s had established two separate points of face-to-face fraternization and this type of meeting was repeated in numerous places along the Western Front. These encounters led to several unofficial agreements to bury the dead, many of whom had been lying out in no man’s land since October. The recent attacks of mid-December had contributed to the macabre scenes, the surviving soldiers wished to bury their comrades out of respect for the dead and to escape the sights and smells. The battalion diarist noted ‘Quiet day. Relieved R. DUB. FUS. in the trenches in the evening’.[43]

Christmas Day

At dawn on Christmas Day, the Warwickshire’s became aware that, unusually, they could see German soldiers on the skyline, ‘heads were bobbing about and showing over their parapet in a most reckless way’, the agreed ceasefire had started.[44] Bairnsfather remarked that:

It was a perfect day, cloudless blue sky; the ground hard and white, fading off towards the wood in low-lying mist. It was such a day as is invariably depicted by artists on Christmas cards – the ideal Christmas Day of fiction.[45]

Private Harry Morgan recorded that at dawn a German soldier with ‘absolutely perfect English’ began an interchange with a Warwick’s soldier and invited him to meet half way. To Morgan and his colleagues surprise they suddenly saw the German stand on top of his parapet ‘in the open and in full view. He then walked towards us and stood in the middle’. Not knowing whether he was full of Christmas spirit or ‘completely round the twist’ the Britons admired his courage and quickly one of them went out and met him and they shook hands. Immediately a crowd of Germans joined them in the middle and then Morgan’s company went out as well.[46] Bairnsfather wrote ‘a complete Boche figure suddenly appeared’ and ‘in less time than it takes to tell, half a dozen or so of each of the belligerents were outside their trenches and advancing towards each other in no-man’s-land’.[47]

Bairnsfather soon joined the men in front of his position and exchanged some uniform buttons with a German officer (Figure 2). He summed up that ‘we both said things to each other which neither understood’ and slowly the meeting dispersed as both sides knew those in authority would not be amused but they parted with ‘a distinct and friendly understanding that Christmas Day would be left to finish in tranquility’.[48]

Figure 2

”Look at this bloke’s buttons, ‘Arry. I should reckon ‘e ‘as a maid to dress ‘im.’

Reproduced by permission of Tonie and Valmai Holt, The Biography of Captain Bruce Bairnsfather, 40.

Hamilton believed that this sudden gathering of foes in no man’s land was due to him. As arranged, he had met a German officer at dawn when we ‘said what we could in double Dutch’ and agreed a 48 hour armistice. Their return to the trenches became the signal for the soldiers to come out to exchange gifts and greetings.[49] Some men went back to their trench and fetched spades to give ‘a decent burial to the dead’, a task previously too dangerous but ‘now both sides were here, working together’.[50] Lt. Black continued his letter to his friend:

On Christmas Day I went over & had a chat with German officers, it was a Saxon regiment, so I enquired for Rossbach & Feist, but nobody knew them, it would have been strange if we had met out there between the trenches. The Germans are just as tired of the war as we are, & said they should not fire again until we did.[51]

Private Tapp’s narrative places him close to Bairnsfather and Morgan as their experiences are very similar, but Tapp adds the interesting detail of attempts to set up a football match:

Xmas morning, get up at 6.30, see all Germans walking about on top of their trenches, now some of them are coming over without rifles, of course our fellows go to meet them including myself, it is a strange sight and unbelievable, we are all mixed up together…we are trying to arrange a football match with them – the Saxons – for tomorrow, Boxing Day…we have arranged not to shoot till 4.30 pm Boxing Day.[52]

Zehmisch also noted attempts to set up a football match on Boxing Day but added that some troops had already played football:

A couple of English brought a football out of their trench and a vigorous football match began. This was all marvelous and strange. The English officers thought so too…for a short while the hated enemies are friends. We agreed not to fire on the following day. Towards evening the officers asked whether a big football match could be held the following day between the two positions but we cannot be sure as a new Captain arrives tomorrow.[53]

This attempt to set up a formal football match was not unique; various sources reference attempts to play on either Boxing Day or New Year’s Day at several points on the line. These plans seem to have been thwarted in all cases by external circumstances.

The football on Christmas Day as described by Zehmisch was not mentioned by any of the Warwick’s at the time but in later interviews Bairnsfather recalled an incident similar to that described by Zehmisch. In an American magazine article in 1929, Bairnsfather remembered that:

At about noon a football match was suggested, someone had evidently received a deflated football as a Christmas present and despite the frozen and pitted surface and the surviving turnips, one of ours brought up a football, blew it up, to kick about.[54]

This story was repeated in greater detail in a Canadian TV interview with Charles Templeton which was broadcast on 12 November 1958. Bairnsfather recollected:

One of our chaps, a sort of Old Bill, had had a football sent out as a Christmas present and blew this up and suggested a game of football with the Germans in no man’s land. Well this was going very nicely and everything, and when suddenly the authorities, the owners and organizers of the war at the back, didn’t like this at all and news came that we had to stop it at once.[55]

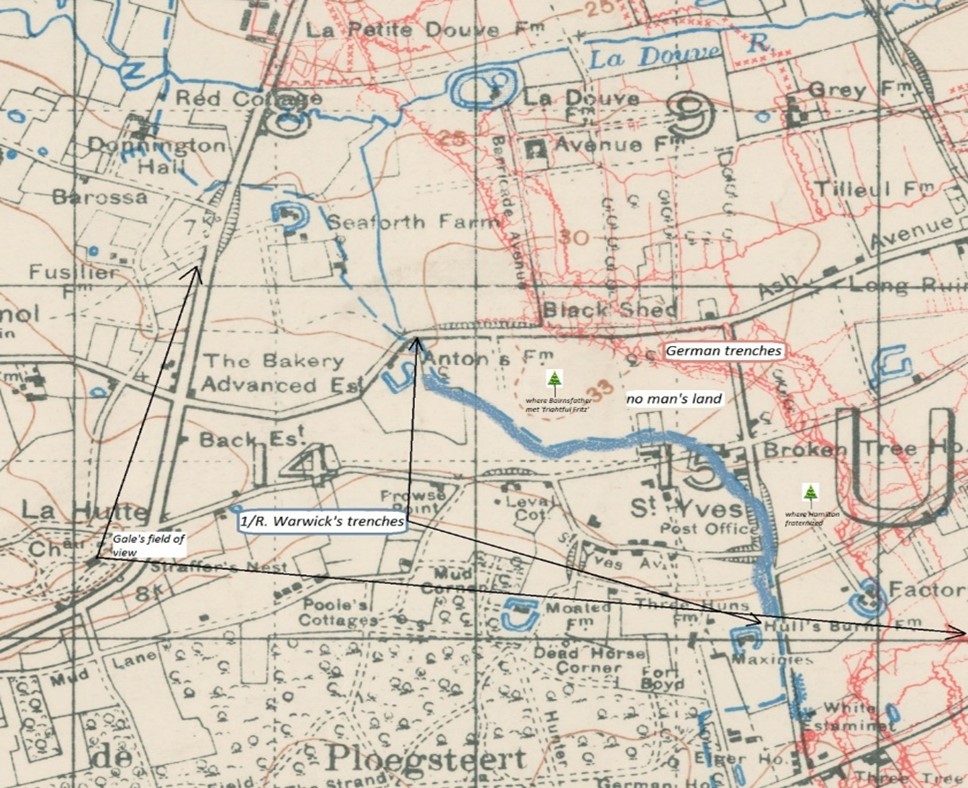

An ‘independent’ witness also reported a football match in the area. Francis Gale, a sergeant in the Royal Garrison Artillery, was an artillery observer at Château de la Hutte on a hill on the north-west fringes of Ploegsteert Wood (Figure 3). He wrote:

A telephone message was received that our boys and the Jerries were fraternising and even playing football at the time. This could plainly be seen from our o.p., a big chateau. The infantry were the Royal Irish Fusiliers, the Warwicks, Gordon Highlanders and I think the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, belonging to the 4th Division.[56]

Figure 3

Château de La Hutte, November 1914

Photograph from the Lt. Col. Haymes collection,

©Imperial War Museum (Q 56161).

Today, due to the density of the Ploegsteert Wood, the only First World War trench positions visible from the ruins of Château de la Hutte are to the north of the woods; this was the area of responsibility of 10 Brigade of the 4 Division at Christmas 1914, which contained the units mentioned by Gale.[57] The Château remains are visible from Bairnsfather’s position in the lines, ‘at the top of a wooded rise in the ground, stood what once must have been a fine château’. The Warwick’s looked ‘on that dear old mangled wreck with a friendly eye; that tapering, twisted, perforated spire…was an everlasting bait to the Boche’; they thought that while it stood they received less shells![58] However, if the woods had suffered severe damage by Christmas 1914, it may have been possible for Gale to observe the trench lines to the east of the woods, the area of 11 Brigade. Perusal of photographs taken inside Ploegsteert Wood at Christmas reveal that, despite it being winter, they were too dense for Gale to see no man’s land to the east through approximately 700 metres of trees (Figure 4).

The War Diaries of the units of the 10 Brigade reveal that the 1/R. Warwick’s and the 2/Seaforth Highlanders were the only units in the line on Christmas Day; the 1/R. Irish Fus. were in billets at La Creche and the 2/R. Dublin Fus. were in reserve at Point 63. The kilted soldiers Gale saw were those of the 2/Seaforth Highlanders who abutted the Warwickshire’s at Anton’s Farm. As Zehmisch does not describe the British footballers as being kilted, a garment which fascinated the Germans, the game he described, and the one seen by Gale, must have involved the Warwick’s (Figure 5).

Figure 4

1/Rifle Brigade after Christmas Dinner in Ploegsteert Wood, 25/12/1914

©Imperial War Museum (Q 11729).

The Warwick’s seem to have been outnumbered in no man’s land during the truce; Tapp noted the ‘gathering of Germans & us, it was one mass, about 150 of them and half as many of us all in a ring laughing and talking’.[59] Just to the south-west, Black became worried because ‘the Germans outnumbered us by 4 or 5 to 1 so I told the Captain I thought we had better get back to our trenches, which we did after a great deal of bowing’.[60] That evening the officers of 1/R. Warwick’s enjoyed a concert in ‘D’ Company’s trench which Hamilton thought ‘was a most enjoyable evening. A very merry Xmas and a most extraordinary one, but I doubled the sentries after midnight’.[61]

The battalion diarist wrote ‘Xmas Day. A local truce British & Germans intermingled between the trenches. Dead in front of trenches buried. No shot fired all day. No casualties’.[62]

Figure 5

Field of view from artillery o.p. at Château de La Hutte.

Trench map section ©National Library of Scotland

Boxing Day, December 26, 1914

The soldiers awoke on Boxing Day to a thin covering of snow and again fraternized until, at 08:40, Lt. Tillyer told all the troops, British and German, to get under cover. HQ had informed the Warwickshire’s commanders that the artillery were going to fire on the German front lines in their section at 09:00; Hamilton recalled the British guns firing on the German second line trenches. The German light artillery responded with some shelling of the Warwick’s lines and Zehmisch was frustrated at the exchange of shellfire, ordering his company to keep down although the shells were falling behind them. After the barrages the truce resumed, Tapp writing that the troops of both sides were all mixed up again; ‘it’s too ridiculous for words’.[63] Hamilton recalls no rifle shots all day and more Christmas presents arrived and they again met the Germans in the middle of no man’s land.[64] Lt. Drummond, a 32 Brigade Royal Field Artillery observer, had heard about the truces on Christmas Day and decided to head to the front lines to experience it. He walked around in the open in Hamilton’s area, noting both the British and Germans digging and repairing trenches and barbed wire entanglements, before entering no man’s land to converse with some of the Germans and exchange souvenirs. Having a camera with him, he lined up some soldiers from each side and recorded the event (Figure 6).[65] There is no mention by members of the Warwick’s or the 134/Saxons, or any independent observers, of the proposed Boxing Day football match. The battalion diarist wrote ‘Truce ended owing to our opening fire. German light gun reply on ‘D’ Coy trenches. 2 wounded. No sniping all day on either side. In the evening German star shells show large party of ‘B’ Coy putting up wire. No shots were fired’.[66]

Aftermath

The Warwick’s were replaced by the Dubliners on the evening of 28 December, Bairnsfather noting that the couple of days after Christmas ‘were of a very peaceful nature, but not quite so enthusiastically friendly as the day itself’.[67] Both Hamilton and Tapp record walking about in the open on 27 December but they did not intermingle with the Germans and both sides constructed new trenches and extended the wire entanglements. On 28 December Hamilton constructed a new dug-out and, with the help of his subalterns, furnished it with table and chairs from the ruined cottages behind the lines.

Figure 6

Soldiers of the 134 Saxons and the 1/R. Warwick’s together, 26 December 1914

Photograph by Lt. Drummond, ©Imperial War Museum (HU 35801).

The diarist reports on the 27 December ‘no sniping. A little shell fire from light guns over ‘D’ Coy. 1 wounded’ and on the 28 December ‘wet day. Great improvements have taken place in the wire in front of our trench. Relieved by R Dub Fusiliers in billets Pt 63’.[68]

The area continued to be peaceful with the Dubliners playing football just behind their trenches on 29 December. The 134/Saxons had been relieved by the 55 Westphalian Regiment and the Westphalian officers noted whilst watching the football that ‘Die Dublin Fusiliers sind gut’.[69] The Warwick’s returned to the trenches on New Year’s Day and although the artillery of both sides were firing; ‘we continue to peacefully look across at each other’.[70] However, the unofficial truce around Ploegsteert came to a sudden end two or three weeks after Christmas when a German walking along his trench’s parapet was shot down by an unknown British soldier. Private Harry Morgan felt:

Unhappy that it was one of us that had broken the unwritten trust. The unfortunate man had no sooner hit the ground, when they hit us with everything they had, a rapid fire to exceed all previous rapid firings. The war was on again with a vengeance.[71]

Remembrance

Dave ‘Taff’ Gillingham co-founded ‘The Association for Military Remembrance 1899-1960’, colloquially known as the Khaki Chums, in 1990 to study the life of the British soldier in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The group, made up of historians, authors and collectors, puts ‘people in the uniform with the right underwear, right food, same kit, the same routine they had’ in order to make them understand experientially what it was like, obtaining knowledge unobtainable ‘in a million years by reading a book or even talking to someone about it’.[72] In 1999, nine Khaki Chums spent Christmas at Ploegsteert where the 1/R. Warwick’s had been in the trenches. They used the same kit as the soldiers of 1914, with no added modern luxuries, to raise money for various military charities.

They arrived on 23 December and departed on the evening of 27 December, similar to the Christmas period the Warwick’s spent there in 1914, the 24 to 28 December. To add to the realism, the worst storm in fifty years hit Belgium in the early hours of Christmas Day quickly raising the water level to about three feet in their trench. At the end of their stay, they refilled their trench and raised a large wooden cross ‘as a mark of respect for those who fought and died in the area’, expecting it to quickly disappear.[73] However, the locals have adopted the cross, at the time the only memorial to the Christmas Truce, set it in a concrete base and regularly treat it with preservative. The ‘Khaki Chums’ cross has become a recognized stop on many tour itineraries and has had an information board erected alongside. Interestingly it has become a focus of football fans’ remembrance and is habitually surrounded by footballs, team scarves and even, sometimes, replica jerseys (Figure 7). These appear to be removed, at least annually, as images of the cross on Remembrance Day, 11 November, usually only show wreaths and small wooden British Legion crosses.

Figure 7

The ‘Khaki Chums’ cross; Anton’s Farm is directly behind the cross and the football pitch is between the England flag and the two trees on the right horizon

Photograph by the author, March 2014.

Discussion

The idea of football being played by the soldiers of both sides in the First World War has caught the imagination of generations. A century on, Prince William claimed ‘it remains wholly relevant today as a message of hope over adversity, even in the bleakest of times’, football is ‘a powerful way to engage and educate young people about such an important moment in our history’.[74] In Britain, the English Premier League, Football League and the Football Association, in collaboration with the British Council, joined forces in a wide initiative called ‘Football Remembers’. This project sent cross-disciplinary education packs, including eye-witness accounts, photographs and reproductions of soldiers’ letters from the British, French, German, Belgian and Indian perspectives, to over 30,000 schools. The British Council CEO, Sir Martin Davidson, said the truce match was an illustration of how ‘people-to-people connections can triumph at a time of global crises’.[75] The Premier League has sponsored an under-12 football tournament at Ypres since 2011 and built a third generation artificial turf community pitch there ‘to create a sporting and cultural experience that lasts beyond the Centenary’.[76] Britain’s First World War and Sports Minister, Helen Grant stated ‘when both sides laid down their arms at Christmas and played football, they showed how sport can overcome even the biggest divide’.[77]

However, there is no objective evidence that any football match took place at any of the Christmas truces along the British line. Football was commonly played in the British army by 1914, especially amongst the working-class soldiers amongst whom it was encouraged by junior officers to help develop fitness and esprit de corps.[78] The troops of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) took it with them to the front, improvising and informally playing whenever possible, even within the sound of the guns.[79] On 2 January 1915 Captain James Jack of the 1/Cameronians noted in his diary that:

The weather remains raw and damp, but apart from colds the health of all ranks is very good. Games, mainly football, in the afternoons keep them fit and cheery…however tired the rascals may be for parades they always have energy enough for football.[80]

John Terraine, Jack’s editor, noted that in July 1915 General Haig, the British First Army commander, after an increase in the number of men being found asleep on sentry duty, wrote in his diary that ‘men should rest during the day when they know they will be on sentry duty at night. Instead of resting they run about and play football’.[81] Football was a consuming passion and sports papers were in great demand at the front as the men tried to keep up-to-date with their team’s performances; professional football in England did not stop until the Khaki Cup Final of 24 April 1915.[82] There were even instances of Germans calling across no man’s land for results, or for sports papers to be thrown over where the trenches were particularly close, to find out how the English and Scottish teams they supported were doing.

Some commentators remain insistent that no football of any sort was played in no man’s land because the ground was too shell cratered and too muddy. However, the weather had turned cold just before Christmas; Bairnsfather recorded ‘the weather has now become very fine and cold. The dawn of the 24th brought a perfectly still, cold, frosty day’.[83] The mud hardened and photographs of the truces show the men standing on a hard surface. Similarly, photographs and reports indicate that the ground, in most places, had not been badly cratered by the artillery at this early stage of the war and informal kick-abouts were certainly viable in some areas. As the war progressed and increasing numbers of artillery guns of heavier calibre bombarded the same areas month after month and year after year, no man’s land became progressively more cratered. The frozen and uneven ground of Christmas 1914 may have made twists and sprains more likely than normal football pitches and some have argued that would have prevented the Tommies playing. However, as evidenced by the Warwickshire’s, officers were involved in the truces and, as in Hamilton’s case, even instrumental to it beginning. Football injuries would have been covered up by the junior officers as normal duty injuries as hundreds were being hospitalized weekly through illness and injury caused by the conditions on the front line.

Others point out that the amount of kit carried to the front would have prevented footballs reaching the firing line and that units with a football would have left them with their valises in battalion transport. However, men did carry them to the trenches, Fred Davidson, the 1/Cameronians medical officer observed ‘the French are always fascinated by the British obsession with football, asking why so many soldiers carry balls strapped to their packs’.[84] Others would have deflated their ball to cram into their packs out of sight of unsympathetic officers; balls of the period did not need special inflation needles and pumps.[85] Newspapers in both Britain and Germany had carried adverts for weeks suggesting items that soldiers might enjoy as Christmas presents and the logistics systems of the enemies strained to deliver the goods. A Queens Westminster Rifleman, Percy Jones, wrote home on 24 December ‘I am keeping well in spite of the large numbers of Christmas parcels received’.[86] Over a quarter of a million private packages were delivered to the BEF in the six days before 12 December and a further 200,000 the following week. It is highly probable that a number of soldiers in each battalion would have received a ball for Christmas and some would have carried them into the lines perhaps looking forward to a game in the reserve positions before being reunited with their valises in billets. Bairnsfather’s account from 1929 suggests this origin for the Warwick’s purported game; ‘someone had evidently received a deflated football as a Christmas present’.[87]

Both Bairnsfather and Zehmisch describe the game they saw as being played with a football, and for Gale to identify football being played over a distance of over a kilometer, from Chateau de la Hutte to the position indicated by Bairnsfather as where he met the Germans in Bullets & Billets, it seems probable that something larger than a tin can was being used. Certainly members of other battalions mention playing football with ball substitutes such as empty tins and straw-stuffed balaclavas. Empty cans were readily available as they were strewn around the barbed wire entanglements to provide last minute warning of enemies approaching as evidenced in photographs of no man’s land and in many Bairnsfather cartoons.[88]

It is puzzling why Tapp and Morgan did not write about football being played if it occurred, especially as Tapp was an enthusiastic Birmingham fan.[89] Perhaps it was such a normal activity in ‘down time’, as described by Jack, that it was not worth writing about whereas a formal match proposed by officers was significant. Many of the participants in the Warwickshire’s truce did not survive the war and accounts of kick-abouts may have disappeared with them. A few weeks after Christmas 1914, the Second Battle of Ypres occurred, 22 April to 25 May 1915, in which the British army lost a further 59,000 men and the 1/R. Warwick’s participated. Morgan wrote about advancing past his platoon officer, or ‘what remained of Lt. Danson, now just a torso, with the men near him unidentifiably scattered over a considerable distance’.[90] Bairnsfather and Morgan ended up on stretchers alongside each other at the Base Hospital at Rouen discussing the truce. The battalion lost eight officers killed and nine wounded or missing, and over 500 other ranks killed, missing or wounded in the early hours of the 24 April.[91] Private Tapp’s diary finishes mid-sentence on 25 April 1915 when he was mortally wounded by a shell. In addition, many records were lost during the Second World War as aerial warfare developed to include large swathes of territory behind the infantry’s front lines.

Conclusion

British Council research has confirmed that the Christmas Truce is one of the most recognized moments of the First World War and more than two-thirds of UK adults are aware of the football matches that took place.[92] However, as Vamplew points out the element of truth in the micro-level myth of Christmas Truce football offers ‘a degree of protection from common-sense rejection’.[93] It is unlikely that any well-organized games that the British Council’s respondents would recognize as a ‘proper’ football match took place. However, it is likely, given the thousands of soldiers milling around no man’s land and the ubiquitousness of football in the BEF, that some had fun on their unexpected holiday playing football using any equipment to hand. One or two accounts mention photographs being taken of football or of participants but none have yet emerged, perhaps there are still some attics awaiting clearance in Britain and Germany.

The most common account of a game involving a real ball involved the 133/Saxons and the 2/Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. Johannes Niemann provided an entertaining description of the German’s roaring with laughter ‘when a gust of wind revealed that the Scots wore no draws under their kilts – and hooted and whistled every time they caught an impudent glimpse of one posterior belonging to one of yesterday’s enemies’. However, the two German officers’ stories, Klemm and Niemann, are not supported by any British sources.[94]

Francis Gale, a trained observer, saw a game of football in front of Ploegsteert Wood at the same location as Zehmisch, a German officer, and Bairnsfather, a British officer, described one being played. Zehmisch and Bairnsfather’s accounts of Christmas Eve are compellingly alike as are their brief descriptions of the troops playing football. These are independent accounts as Zehmisch’s diary remained unknown until after his death in 2000 and it was written contemporaneously with the event, over a decade before Bairnsfather’s story was published in 1929 in America. It is highly probable that both Zehmisch and Bairnsfather were unaware of Gale’s story printed in the inner pages of The Daily Chronicle in 1926.

The evidence seems to suggest that the strongest case for a game being played with a real football is amongst the soldiers of the 1/R. Warwick’s and the 134/Saxons at the site now overlooked by the Khaki Chums cross, with its accompanying football memorabilia.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful for the thoughtful comments and insights offered on an early version of this paper by the participants of the annual conference of the British Society of Sports History at Leeds Beckett University, September 2014. I particularly thank Dr Trevor Petney of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany, for his translations of German material.

References

[1] Mark Marsay, ‘Preface’ in Bruce Bairnsfather, The Bairnsfather Omnibus: Bullets & Billets and From Mud to Mufti (Scarborough: Great Northern Publishing, 2000), xiii.

[2] Bill Mauldin, interview by Frank Wood, Close Up, CBC TV, November 12, 1958; http://www.cbc.archives/categories/war-conflict/first-world-war/the-first-world-war-cartoonist-bruce-bairnsfather.html (accessed 18 October 2014).

[3] Marsay, ‘Preface’, xiii.

[4] Tonie and Valmai Holt, In Search of the Better ‘Ole: A Biography of Captain Bruce Bairnsfather (Barnsley: Leo Cooper, 2001); Marsay, ‘Preface’.

[5] Andrew Hamilton and Alan Reed, Meet at Dawn, Unarmed: Captain Robert Hamilton’s Account of Trench Warfare and the Christmas Truce in 1914 (Warwick: Dene House, 2009), but Marsay has him escorting a hundred replacement soldiers from England on 28 and 29 November and not arriving at the front until four or five days later. Each battalion kept an official War Diary, Form C. 2118, which provided a daily account of the unit. They were written up by a specified junior officer before being signed off by the battalion commander. Unusually the ‘War Diary, 1st Battalion Royal Warwicks, Aug-Dec 1914: 4th Division, 10th Infantry Brigade’, The National Archives WO 95/1484/1 (War Diary, 1/R. Warwick’s), does not record Bairnsfather’s arrival. In many War Diaries, specific officers’ activities such as arrivals, going and returning from leave, injuries and fatalities are normally recorded.

[6] War Diary, 1/R. Warwick’s.

[7] Robert M. Citino, ‘The Birth of German Militarism: The Legendary, Victorious Campaigns of the Great Elector, Frederick William I’, The Quarterly Journal of Military History, 26 no. 2 (2014): 30-37; Holger H. Herwig, First World War: German and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918 (London: Arnold, 1996).

[8] Herwig, First World War. This comprised about a fifth of France’s most productive territory.

[9] Marc Ferro, The Great War, 1914-1918 (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1969), 75.

[10] David Stevenson, 1914-1918: The History of the First World War (London: Penguin, 2004); Bruce Bairnsfather interview by Charles Templeton, Close Up, CBC TV, 12 November 1958; http://www.cbc.archives/categories/war-conflict/first-world-war/the-first-world-war-cartoonist-bruce-bairnsfather (accessed 18 October 2014).

[11] Paul Fussell, ‘The Troglodyte World’, in The Great War and Modern Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975), 36-74 provides a reflective view of life in the trenches. Typically the support trenches were 100 metres behind the firing line and connected by communication trenches. The reserve trenches lay a further 4-500 metres back connected to the support trenches by communication trenches.

[12] Francis Henry Black, ‘letter to Alf, 2 December 1914’ in ‘Private papers’, Imperial War Museum, Documents 4333 82/3/1.

[13] War Diary, 1/R. Warwick’s.

[14] Black, ‘letter to Alf’. Every officer was assigned a soldier-servant and it was seen as a desirable position as they often avoided more onerous duties; the term was changed to batman between the wars.

[15] Bruce Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets (London: Grant Richards, 1916), 15.

[16] War Diary, 1/R. Warwick’s.

[17] Private William Tapp, ‘Private papers’, Imperial War Museum, Document 18524. In January 1915, 2,365 British troops were temporarily removed from the trenches with trench foot, rheumatism and trench fever compared to 155 killed and 415 wounded by enemy action.

[18] Bruce Bairnsfather, Fragments from France (London: G.P. Putnam’s, 1917), 81.

[19] Hamilton and Reed, Meet at Dawn, 99.

[20]Lawrence Sondhaus, World War One: The Global Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

[21] Tapp, ‘Private papers’.

[22] John Horne and Alan Kramer, German Atrocities 1914: A History of Denial (London: Yale University Press, 2001).

[23] By November, The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had suffered 90,000 men killed, missing or wounded; the Germans and French about one million killed, missing or wounded each. Moving equipment was also a problem, the British army requisitioned over 300,000 horses and mules in the first twelve days of war, but they required training. Out of the 25,000 animals in service with the British army at the outbreak of war, 13,500 had been killed by Christmas. See Michael Clayton, ‘From British Ditches to Foreign Trenches’, The Field, 324 no. 7321 (August 2014): 94-97.

[24] A.E. Henry Morgan, Our Harry’s War 1914-1918: A Fight for Survival (Hartley Wintney: Rydan, 2002), 48. Private Morgan was in ‘C’ Company, 1/R. Warwick’s.

[25] For example, in a drawing resembling Tapp’s story of informal shooting competitions, Illustrated Evening News, December 26, 1914, 878-879 published an image by A.C. Michael showing ‘an Anglo-German “Bisley” at the front’ with a German soldier setting up a target in no man’s land for British troops. Despite being in the Christmas issue, this must have been prepared well before news of the Christmas Truces reached Britain.

[26] Malcolm Brown and Shirley Seaton, Christmas Truce: The Western Front, December 1914 (London: Pan, 2001).

[27] Brigadier General Hull, ‘Operational Order No. 1, 18-12-14’ in War Diary, 1/Royal Warwick’s.

[28] Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets, 27. The War Diary reports ‘B’ Company on the right offered enfilading support to the attack with one machine gun.

[29] According to Hamilton and Reed, Meet at Dawn, the attack on the Warwick’s right cost ten officers killed and three wounded, sixty-five other ranks killed and 119 wounded, and thirty men missing (killed or taken prisoner).

[30] The tremendous pace of the war had left insufficient time for necessary maintenance to equipment and many artillery pieces were worn out and would require new barrels to regain accuracy.

[31] Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets, 27.

[32] War Diary, 1/Royal Warwick’s.

[33] General Headquarters (GHQ) message, Imperial War Museum PRO WO 95/1440 .

[34] Leutnant Kurt Zehmisch ‘Diary’, photocopy in the archives of the In Flanders Museum (IFF), Ypres, Belgium. Zehmisch’s diary was discovered in his attic in the village of Weischlitz in Saxony following his death in 2000 by his son Rudolf.

[35] Michael Jürgs, Der KleineFriedenimGrossen Krieg (München: C. Bertelsmann, 2003).

[36] Zehmisch, ‘Diary’.

[37] Tapp, ‘Private papers’.

[38] Hamilton and Reed, Meet at Dawn. Hamilton had fired Gregory as he could not make a decent cup of tea.

[39] Black, ‘letter to A.H. Seamons, 31 December 1914’ in ‘Private papers’.

[40] Hamilton and Reed, Meet at Dawn.

[41] Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets; Tapp, ‘Private papers’.

[42] Tapp, ‘Diary’ in ‘Private papers’.

[43] War Diary, 1/R. Warwick’s.

[44] Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets, 31.

[45] Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets, 30-31.

[46] Morgan, Our Harry’s War, 47.

[47] Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets, 31.

[48] Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets, 33.

[49] Hamilton and Reed, Meet at Dawn, 111.

[50] Morgan, Our Harry’s War, 48.

[51] Black, ‘letter to A.H. Seamons’ in ‘Private papers’.

[52] Tapp, ‘Private papers’.

[53] Zehmisch, ‘Diary’.

[54] Bruce Bairnsfather interview in a 1929 American magazine article, cited by Newark Advertiser, March 14, 2014.

[55] Bruce Bairnsfather interview by Charles Templeton, Close Up, CBC TV, November 12, 1958; http://www.cbc.archives/categories/war-conflict/first-world-war/the-first-world-war-cartoonist-bruce-bairnsfather.html (accessed 18 October 2014).

[56] Francis J. Gale, ‘letter’, Daily Chronicle, November 24, 1926.

[57] Research visit by author, March 2014.

[58] Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets, 17

[59] Tapp, ‘Private papers’.

[60] Black, ‘letter to A.H. Seamons’.

[61] Hamilton and Reed, Meet at Dawn, 112.

[62] War Diary, 1/R. Warwick’s.

[63] Tapp, ‘Private papers’.

[64] Hamilton and Reed, Meet at Dawn.

[65] Cyril Drummond, ‘Private papers’, Imperial War Museum, Documents 1694.

[66] War Diary, 1/R.Warwick’s. Although the diaries were usually written by junior officers, at this stage of the war these men were still generally regular officers who had planned a career in the army. Knowing that high command disapproved of any fraternization, reports were circumspect. It is probable that incidents of fraternization were far more widespread than were reported. The War Diary of the 1/The Buffs (East Kent) is missing its pages from December 21-29; perhaps the battalion commander feared any detailing of fraternization risked raising the wrath of GHQ. Stanley Weintraub, Silent Night: The Remarkable Christmas Truce of 1914 (London: Simon & Schuster, 2001) details a football match between the 1/The Buffs and the Germans as recalled many years later by William Dawkins. Was this described in the War Diary?

[67] Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets, 33.

[68] War Diary, 1/R. Warwick’s.

[69] Jürgs, Der KleineFriedenimGrossen Krieg, 170

[70] Hamilton and Reed, Meet at Dawn, 121.

[71] Morgan, Our Harry’s War, 49.

[72] Taff Gillingham – Khaki Chum and history man. EADT24, 15 April 2010, www.eadt.co.uk/new/features/taff_gillingham_khaki_chum_and_history_man_1_21372 (accessed 10 October 2014).

[73] Taff Gillingham, ‘Christmas Truce 1914-1999’, www.hellfirecorner.co.uk /chums.htm (accessed 10 October 2014).

[74] Prince William, ‘Prince William wants memorial to WW1 truce football match’, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk–27327162, May 9, 2014 (accessed 12 October 2014).

[75] Sir Martin Davidson, British Council Chief Executive, ‘Duke of Cambridge kicks off “Football remembers”, www.britishcouncil.org/…/duke-cambridge-kicks’football-remembers’ (accessed 12 October 2014).

[76] Richard Scudamore, Premier League Chief Executive, ‘Duke of Cambridge kicks off “Football remembers”, www.britishcouncil.org/…/duke-cambridge-kicks’football-remembers’ (accessed 12 October 2014).

[77] Helen Grant, ‘Duke of Cambridge kicks off “Football remembers”, www.britishcouncil.org/…/duke-cambridge-kicks’football-remembers’ (accessed 12 October 2014).

[78] Tony Mason and Eliza Riedi, Sport and the Military: the British Armed Forces 1880-1960 (Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 2010).

[79] Iain Adams, ‘Football: A Counterpoint to the Procession of Pain on the Western Front, 1914-1918?’, Soccer & Society, 16 nos. 2-3 (2015): 217-231.

[80] John Terraine, General Jack’s Diary (London: Cassell, 2000), 91.

[81] Terraine, General Jack’s Diary, 91.

[82] Sheffield United beat Chelsea 3-0 in front of 50,000 people at Old Trafford in the FA ‘Khaki Cup Final’.

[83] Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets, 29.

[84] Andrew Davidson, Fred’s War: A Doctor in the Trenches (Edinburgh: Short Books, 2013), 208.

[85] Iain Adams, ‘Over the Top: “A Foul; a Blurry Foul!”’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 29 no. 6 (2012): 813-831.

[86] Eksteins, Rites of Spring, 112.

[87] Bairnsfather interview in an American magazine 1929, cited by Newark Advertiser, March 14, 2014.

[88] Imperial War Museum photograph Q 49102 shows a plethora of empty cans in front of the British wire near La Boutillerie in the Christmas 1914 period; Bairnsfather features empty tins in many cartoons including ‘The New Submarine Menace’, ‘Poor Old Maggie’, ‘The Tin Opener’ and ‘That Hat’.

[89] Hamilton and Reed, Meet at Dawn.

[90] Morgan, Our Harry’s War, 61.

[91]Morgan, Our Harry’s War; Holt and Holt, In Search of a Better ‘Ole; Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets.

[92]‘Duke of Cambridge kicks off “Football remembers”, www.britishcouncil.org/…/duke-cambridge-kicks’football-remembers’ (accessed 12 October 2014).

[93] Wray Vamplew, ‘Exploding the Myths of Sport and the Great War: a first salvo’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 31 no. 18 (2014): 2.

[94] Iain Adams and Trevor Petney, ‘Germany 2 – Scotland 2, No Man’s Land, 25th December 1914: Fact or Fiction?’ in Jonathon Magee, Alan Bairner and Alan Tomlinson, eds, The Bountiful Game? Football Identities and Finances (Oxford: Meyer and Meyer, 2005), 21-41.