Playing Past is delighted to be publishing on Open Access – Sport and Leisure on the Eve of World War One, [ISBN 978-1-910029-15-2] – This eclectic collection of papers has its origins in a symposium hosted by Manchester Metropolitan University’s Sport and Leisure History research team on the Crewe campus between 27 and 28 June 2014. Contributors came from many different backgrounds and included European as well as UK academics with the topics addressed covering leisure as well as sport.

Please cite this article as:

Knuts, Stijn. The First Miles of a Double-Edged National Sport: Cycling, Society and (sub)National Identity Construction during the Belgian Belle Époque, In Day, D. (ed), Sport and Leisure on the Eve of World War One (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2016), 47-71.

3

______________________________________________________________

The First Miles of a Double-Edged National Sport: Cycling, Society and (sub)National Identity Construction during the Belgian Belle Époque.

Stijn Knuts

______________________________________________________________

Abstract

Belgium witnessed incisive social, political and cultural changes in the decades preceding the Great War. These changes were both reflected in and influenced by the contemporary evolution of the sport of cycling. Between the 1880s and 1914, the bicycle’s consumption in Belgium evolved from a mostly bourgeois affair to an increasingly ‘democratized’ one. As the bicycle became the vehicle par excellence for mass leisure and mobility, its sportive use evolved as well. While bicycle racing had already experienced a first wave of popularity in the 1890s, this was also a predominantly bourgeois affair. Conversely, it was the new mass of lower class cyclists that brought new momentum to the sport in the 1900s when their growing interest in bicycle racing caused the emergence of a vibrant ‘sports-media-industrial complex’. In mutual symbiosis, the sports press, bicycle manufacturers and the growing number of racers turned racing into the country’s most successful and arguably first mass-spectator sport. The victories of Flemish racer Cyrille Van Hauwaert were especially important symbolic episodes in giving momentum to this dynamic. At the same time, the rapid transformation of racing had effects on its representation as a vehicle for (sub)national identity as well. The growing part played by Flemings in the sport enticed pro-Flemish sports titles like Sportwereld to construct a discourse in which racing was imagined as an essentially Flemish practice, expressive of a distinct, subnational Flemish identity that was also championed by the country’s increasingly active socio-political Flemish movement.

Keywords: Cycling; Belgium; Nationalism; Cyrille Van Hauwaert; Flemish Movement.

Introduction

Why are Belgians so infatuated with bicycle racing? To many Belgians, racing is the ‘national sport’ par excellence, a constituent part of national culture.[1] The question, however, can also be put differently: why are Flemings so infatuated with racing? Indeed, to many in the country’s Dutch-speaking Flemish part, bicycle racing is also – or especially – a typically Flemish sport. In almost mystical terms, ‘de koers’ (the colloquial Flemish word for the sport) is presented as expressing an elusive Flemish ‘essence’. Nowhere is this more obvious than during the Tour of Flanders race, a site for annual celebrations of Flanders’ ‘unique’ racing culture as a powerful cultural symbol of Flanders and its people.[2] This ‘Ronde van Vlaanderen’ has earned a solid place in Flemish collective memory – as have the region’s many racing champions. Cycling thus is a potent marker of both Belgian and Flemish cultural identities, a twofold ‘national sport’. This constellation, I want to argue, has its roots in the years preceding the Great War.

The period between 1880 and the start of the First World War in 1914 was a crucial one for Belgium’s social, cultural, political and economic development. In the three-odd decades before the War, the small nation witnessed evolutions that strongly determined the course of twentieth-century Belgian society and culture. It is hardly surprising, then, that in her history of Belgium during the Great War Sophie De Schaepdrijver included a lengthy introductory chapter on this period.[3] Indeed, these thirty or so years were a period in which the little country became in many ways a world power. Economically, it became a commercial and industrial powerhouse, with a solid place in the top five of the world’s strongest economies, a position based on its fast-growing port city Antwerp, Walloon steel production and the international activities of Belgian entrepreneurs. In terms of empire as well, Belgium became a high-roller. In 1885, its ambitious monarch Leopold II acquired the Congo Free State as private property. Although internationally criticized for his cruel treatment of the native population, the money he earned from its rubber production caused an inflow of wealth into the country, which the King spent on the embellishment of the capital city of Brussels. In 1908, shortly before the King’s death, this Congo became a state colony. Culturally, too, Belgium became a force to be reckoned with. Not only was Brussels a hub for the international avant-garde art of the period but, as a conscious strategy, Belgium presented itself as an international hub of European civilization. This successful tapping of the internationalist current in Europe aimed at providing the officially neutral country with ‘peace, progress and prestige’, and was especially evident from the many international congresses on themes like science, education and sport which took place on its soil, the no less than seven World Fairs held in its cities between 1880 and 1914, or in the prominent role of Belgians in new international organizations, which often had their seat in Brussels.[4]

In spite of all these good tidings, this was also a period of intense political and social domestic conflict. The Belle Époque was especially a bourgeois one, favoring those already in a social or economic elite position. Beneath this affluent top layer, discontent began to stir. The liberal Belgian economy was good for entrepreneurs but not for the laboring masses, who were subject to low wages and bad working conditions. This led to a growingly combative workers’ movement and, especially, to the bloody riots of 1886 in the Walloon industrial areas, which sent a shockwave through bourgeois Belgium. To quell new revolutionary manifestations, the country’s governments began to gradually enact a wide-ranging social policy to alleviate the worst of the working masses’ conditions and gradually integrate them into bourgeois society. Not fast enough, however: while the country’s restrictive census voting system was replaced by general plural voting in 1893, which gave every male a vote but also gave more than one to those with money and education, protests and strikes for a true general enfranchisement rocked the country right up to 1914. These protests were spearheaded by the socialist Belgian Workers’ Party, one of the main expressions of the growing but still contested role of the masses in society.[5] Between the country’s main language groups, things were heating up as well. For decades, a French-speaking elite had dominated the country, even in the country’s Flemish part, which had a Dutch-speaking majority. From the 1840s onwards however, a so-called Flemish Movement took shape, which demanded a bigger role for Flemings and their language in the country’s government and judiciary. Around 1890 this Flemish movement increasingly transformed from a small group into a mass movement, which demanded equal rights for a socially, culturally and economically disadvantaged Flemish ‘people’ with an ever louder voice. Within this movement, the idea that there existed a separate Flemish people and identity became increasingly prevalent.[6]

It was in this turbulent context that Belgian cycling took its first steps. The advent of the bicycle in Belgium was not only thoroughly influenced by all the developments just outlined in its practice, organization and ideology. More so then being just a passive receptacle for these broad evolutions, cycling also shaped them. Especially after 1900, as different actors tried to influence broader social and political evolutions through the appropriation of cycling’s use and meanings, the bicycle, whether used for utilitarian, recreational or sporting purposes, increasingly became a socially and culturally meaningful commodity. As this paper explores, this was especially the case in two fields, both being essential to the establishment of cycling as a marker of both Belgian and Flemish identities. On the one hand, the changing sociopolitical position of the lower classes was expressed through changing cycling practices and the discourses surrounding them. On the other hand, the growing cultural and political awareness of Flemings led to the first manifestations of the expression of cycling as quintessentially Flemish.

Early days: cycling as bourgeois sport and leisure

The introduction of the bicycle in Belgium in the late 1860s, shortly after its conception in France, marked the beginning of cycling in the country. A growing number of new vélocipèdistes took to the streets, while the first clubs for cyclists were formed in Brussels and Ghent in 1869. This cycling ‘hype’, however, was short-lived: when the Franco-Prussian war erupted in 1870, the collapse of the burgeoning French cycling culture negatively influenced Belgium as well.[7] Around 1880, cycling got a second wind, when a new bicycle type called the Ordinary, characterized by a gigantic front and minuscule back wheel, was introduced. In the early 1880s, new cycling clubs were established in many of Belgium’s cities. These collectives, like cycling in general, were dominated by young, urban upper- and middle-class males, who had the time, physique and financial means to ride the expensive, physically challenging Ordinary. The embryonic sport of bicycle racing profited from its introduction and over the course of the 1880s the number of races, usually organized on improvised street circuits in city centres, grew substantially.[8]

This growth also engendered the first attempts at organizing cycling on a national level. On 21 January 1883, six clubs established the Fédération Vélocipédique Belge (FVB), the country’s first national cycling association. While this FVB soon organized national racing championships (1884) its activities stalled after a few years, leading to the secession of a number of discontents and the formation of a rival association, the Union Vélocipédique Belge (UVB), in 1888. Only in April 1889 was an end put to the quarrelling between both associations which had severely weakened the sport, as the FVB and UVB merged into a new Ligue Vélocipédique Belge (LVB).[9] Its advent proved timely. The safety, a new, chain-driven bicycle type with equally-sized wheels and fitted with pneumatic tires from 1888 onwards, was fast becoming popular. Faster and easier to use, it soon relegated the Ordinary to obscurity.[10] The number of cyclists in the country grew quickly. Initially, this growth remained limited to the major cities’ bourgeoisie, the traditional bulwarks of cycling. As the decade progressed however, smaller towns and villages, even in thinly-populated areas saw cyclists appear – although here too, they hailed from the local elite.[11] Moreover, while the 1880s had seen only few women cycle, a growing number of them now did. Despite intense debates on the propriety and physical effects of cycling on women, most male cyclists welcomed a presence that, in any case, strengthened the image of cycling as offering a new degree of relational and even sexual freedom. To women themselves, in turn, cycling signified greater independence in both movement and consumption.[12]

Figure 1

Learning to ride the safety bicycle or bicyclette, the main catalyst for the international and Belgian ‘bicycle craze’ of the 1890s

Source:Musée de la vie wallonne, Liège

Even more so than growing numbers of practitioners, the new bicyclette gave shape to what would become some of cycling’s distinctive practices. Cycling excursions in the countryside were now on the rise, as a growing group of bicycle ‘tourists’ rode out in quest of new aesthetic sensations or fun-filled sociability among equals, combining cycling with games or picnicking.[13] Racing experienced rapid growth as well, with the introduction of long-distance road competitions like Paris-Brussels (1893). Simultaneously, the construction of vélodromes (closed-circuit cycling tracks) expanded: by 1895, all major Belgian cities had at least one such track. This growth also engendered a shift from the sport’s organization from the British principles of amateurism – which barred racers from earning money through their sport and was a strong force in Belgium in the 1880s – to professionalism, which allowed racers to earn money. While this went far from smoothly, under the pressure of the increasing preference of Belgian riders for professional French racing, the LVB eventually allowed professionals in 1893.[14]

In subsequent years, Belgian racing became strongly professionalized and commercially oriented, with bicycle manufacturers sponsoring racers to market their products.[15] Belgian racers became increasingly internationally active. Certainly the sprinters Robert Protin and Hubert Houben became true international racing stars, with the highly-publicized series of duels between both in Brussels and Liège in 1895 significantly boosting the sport’s popularity in Belgium.[16] A fast growing, specialized cycling press was both a consequence of and a catalyst for this ‘bicycle craze’. Periodicals like the LVB‘s Revue Vélocipédique Belge (1889) or dailies like Le Véloce (1893) and dozens of smaller titles not only informed cyclists on their favourite pastime. Their discourses also determined trends and best practices.[17] This expansion, however, also created a growing rift between racing and bicycle tourism. During the 1880s, racing and leisure cycling were still part of the same new phenomenon that was the bicycle, but growing specialization now led bicycle users to focus on one or the other. Recreational cyclists, especially, became discontented with the LVB‘s growing focus on racing. Indeed, while it claimed to represent both forms of cycling most of the association’s rules pertained to sport instead of tourism.[18] This uneasy situation soon led to the emergence of rivals to its authority. In 1895, discontented bicycle tourists established a Touring Club de Belgique (TCB). Modelled on similar associations in France and Britain, it aimed at attracting the growing number of individual leisure cyclists in the country and supporting their bicycle tourism by, for instance, publishing travel itineraries or lobbying for better roads. It soon became bigger than the LVB.[19] The latter, while vigorously fighting the TCB in course of the next few years, in many ways remained a sport-dominated organization.

Notwithstanding the polemics between the two associations, both strived towards the same objective: legitimising and strengthening the new bicycle’s place in society. Indeed, despite its growing popularization the vehicle was still subject to widespread criticism during most of the 1890s.[20] To counter this perception, both LVB and TCB – with a mixture of strategy and conviction – presented cyclists as respectable bourgeois citizens engaged in practices which were not ‘simply’ leisure or sport. Cycling, in their imagination, was a form of physical exercise that improved one’s health, energy, and mental well-being. The new technology created a new class of strong, self-conscious men, perfectly suited to the challenges of modern, industrial urban society. Playing a crucial role here was the fact that the bicycle’s mobility enabled its users to ride out of the crowded, industrial cities they lived in, which were increasingly seen as mentally and physically damaging, and venture into the ‘healthy’ green space of the countryside.[21]

These physical and mental advantages were often linked directly to the fate of the Belgian nation. By making the Belgian people healthier and physically fit, cycling contributed to the country’s strength, internal stability and international prestige. Victories in international racing events like that of André Henry in the highly-publicized Paris-Brussels road race of 1893 were put forward as symbols of the prowess of ‘little Belgium’ vis-à-vis its larger European neighbours in the cycling press. Touristic excursions, in their turn, were believed to instruct cyclists on their nation’s history and on the beauty of its nature, inciting their patriotism. The incessant campaigning of both associations to the government for better roads and, most notably, the construction of cycling paths, was coated in this language. According to some, better roads for cyclists would even boost the country’s economy by attracting tourists from other countries. After 1895, the government increasingly began to honour cyclists’ demands.[22]

This presentation of the bicycle was closely linked to the self-image and social aspirations of many in cycling’s top ranks. Often located in bulwarks of the country’s Liberal Party like Antwerp, Liège or Brussels, these prominent cyclists associated themselves with a progressive, liberal world view.[23] All this did not mean organized cycling was a party political vehicle. In order to build as broad a support base as possible in a country which, after all, was dominated by Catholic governments between 1884 and 1917, both LVB and TCB continuously stressed their political neutrality, and claimed to work for all Belgians.[24] In this sense, the patriotic discourse they connected to the bicycle was one which aimed at legitimizing their activities as being truly ‘national’, uniting and benefiting the nation as whole. This strong and often sincerely felt nationalism of both associations’ top ranks was translated into a plethora of actions. Both, for instance, conspicuously professed their attachment to the Belgian royal family to obtain additional leverage in their quest for legitimacy for the bicycle. Their incessant campaigns for having the bicycle adopted by the Belgian Army, too, could be seen as having the same goal.[25]

Masses in the saddle

Around 1900, this strongly bourgeois cycling culture was subject to a range of incisive changes. The growing popularity of the motorcycle and the automobile from the later 1890s onwards led a growing number of well-heeled bourgeois to move away from cycling. Bicycle, automobile and motorcycle closely resembled each other in terms of their users’ motivations and experiences. All three were vehicles on which the (male) bourgeois experienced new speed, power and mobility, and were important for their users’ social distinction.[26] The still expensive automobile and motorcycle were thus bestowed with the same aura of modernity the bicycle enjoyed during the 1890s. The latter, however, no longer subject to any significant improvements, was now increasingly seen as ‘ordinary’. This was only added to by the fact that price drops and rises in living standards now made the bicycle increasingly affordable to society’s lower echelons. With the total number of Belgian cyclists rising from 90,000 in 1899 to over 500,000 in 1912 (out of a population of 7.5 million), the bicycle became less suited to conspicuous consumption. Working-class figures now increasingly united themselves in cycling clubs as well, as the bicycle became ‘the most popular, cheapest and fastest means of transport available’, used by the masses for leisure outings and riding to work.[27]

As the upper and middle classes moved away from the bicycle, the previously booming culture of Belgian organized cycling experienced difficulties. Certainly racing suffered, with numerous cycling tracks closing down around 1900.[28] While the TCB managed to limit the effects of this transformation, rebranding itself as an association catering to all kinds of tourists and with a growing focus on automobile users, the racing-oriented LVB suffered.[29] While active members were hard to find and its finances dwindled, even the association’s periodical ceased publication in 1902.[30] As a way to fight the crisis, the LVB began to devote attention to the motorcycle – as a ‘motorized bicycle’ – a move which was only partially successful.[31] In addition, the growing democratization of the bicycle’s consumption led to the emergence of new rivals for the LVB‘s authority as, in more peripheral parts of the country like Limburg (1900), new regional cycling associations now united a growing number of lower-class cyclists independently from the LVB.[32] Nevertheless, both the LVB and the TCB also saw opportunities in the bicycle’s democratization. From the early 1900s onwards, both began campaigning for the lowering of the taxes on bicycle use levied by the country’s provinces since 1892. The tax had been a demand of cyclists themselves in the early 1890s, as a way of financing the road improvements they required from the government. Now, they wanted it lowered in order to make cycling more affordable to the country’s working classes. In an evolving discourse, the bicycle increasingly came to be seen as a facilitator of a stable society, socially integrating the urban proletariat by allowing them to move into a healthy countryside benefiting their morals and hygiene, as well as keeping them away from alcoholism by stimulating them to ride home after work instead of staying for drinks.[33]

That the crisis gripping cycling around 1900 was also grounds for its transformation was equally evident in racing. Almost at the same time as the sport’s popularity declined in the country, new initiatives tried to reinvigorate it. A growing group of racing personalities began to take increasing issue with the impact of professionalism, seeing the commercial and financial interests it had brought to the sport as one of the main causes of its decline. In the LVB, supporting amateur racing again became one of the association’s goals, a move which was imagined as a return of the ailing sport to its ‘pure’ form. With some success: by 1905, amateurism was again practiced by a growing number of clubs, mostly in the remaining bourgeois vestiges of cycling in the big cities.[34] During the early 1900s, moreover, this reorientation on amateurism found an additional champion in the Union Belge des Sociétés de Sports Athlétiques (UBSSA, 1895), a strictly amateur sporting association also active in football and athletics which set up an expanding network of amateur road and track races as well. Of course, the UBSSA‘s focus on amateurism in a time in which the LVB did the same regularly caused tensions between both. Episodes of uneasy power-sharing were followed by open conflict.[35]

Paralleling this largely bourgeois-led amateurism revival, however, the growing number of lower-class cyclists began to compete in a new kind of racing circuit. Already from the middle of the 1890s onwards, when racing had first spread outside the country’s major cities, countryside towns and villages had seen small-scale road races or cycling competitions inspired on folk games such as jousting take place, often on the occasion of the town fair or ‘kermesse’.[36] From the later years of the decade on, these small-scale races became increasingly prevalent. In 1898, the Cycliste Belge Illustrée noted how ‘not even the smallest village fair does not have its bicycle races on the program of its festivities’.[37] As low-threshold occasions for participating in the sport, these ‘courses de kermesse’ or ‘street races’ soon became a constituent element of Belgian racing. Especially these practices’ association with the town fairs was important. An event with pre-modern and religious roots, the ‘kermis’ was a high-point in many towns’ social and commercial life, and received a lot of support from local governments. Continuously looking to adapt to the times, those involved in composing the fairs’ programmes quickly became convinced of the sport’s potential for attracting crowds.

Cycling clubs were a crucial actor in the coming about of these races, as they had the expertise to organize them. In doing so, they made effective use of the argument that racing attracted a crowd and increased the revenue of local traders. In 1910 for instance, clubs in the small Eastern-Flemish city of Eeklo supported their request for municipal subsidies for the organization of cycling races to the town council by pointing out the ‘good trade’ the popular sport engendered for the town’s tradesmen.[38] Supported materially and financially by local shopkeepers or publicans, as well as by local politicians wanting to increase their popularity, racing thus became a staple feature of local festive culture. Throughout the pre-war years, these local races continued to grow in number. This was not to say they went unchallenged. Certainly during their early years, the growing public appearance of a new kind of ‘shabby’ lower-class racer that they entailed was regularly denounced as endangering the public order. In 1898, the Belgian Minister of Public Works even advised all provincial governments to prohibit racing on public roads. However, his attempt had little effect, as had later, similar propositions to curtail racing out of concerns for public safety and propriety. As Raoul Claes of the LVB argued in 1898, the importance of these races to the local economy would make outright prohibiting them a highly unpopular move.[39]

The development of this local racing circuit signified an important episode in racing’s transformation from a bourgeois-dominated to a mass sport, not in the least because these races functioned as a training ground for a new generation of successful Belgian racers. The provinces of West- and East-Flanders, where this new racing culture was especially vibrant, were a crucial site here, as the surprising victories of the West-Flemish ‘street racer’ Cyrille Van Hauwaert in prestigious French road races like Bordeaux-Paris (1907) and Paris-Roubaix (1908) became a symbolic rallying point for the sport’s new momentum. After Van Hauwaert’s breakthrough, the number of internationally successful Belgian racers increased exponentially. Belgians, for instance, won all editions of the Tour de France (1903) between 1912 and 1914, while in the country itself new professional road races like the Tour of Belgium (1908) were established and new cycling tracks built.[40]

In this new momentum for racing, the sport press played a crucial role. The many new titles emerging during the later 1900s in response to racing’s growth in their turn further stimulated the sport’s expansion. Already before 1914, two dominant players in this reinvigorated sports press emerged, the Flemish journal Sportwereld (1912) and the francophone Le Vélo (1908).[41] From their onset, these titles sponsored or organized races themselves. Some of the period’s most remarkable new events, such as the Tour of Flanders (Sportwereld) were set up by them. Simultaneously, these titles were closely linked to the Belgian and especially French bicycle producers now sponsoring the growing number of professional Belgian racers. To these companies, these titles were crucial forums for the commercial exposure of their products.

As such, after its first emergence during racing’s initial boom in the 1890s a new, even stronger ‘sports-media-industrial complex’ was formed that was crucial to racing’s further expansion, bringing together racers, the sports press and bicycle manufacturing companies in a triangular relationship in which the financial and commercial interests of all three were continuously strengthened.[42] Indeed, as professional racing regained its bearings, amateur racing again lost ground. While the LVB had few problems in adapting to professionalism’s new dominance, its rival UBSSA now experienced problems. In 1911, the LVB/BWB dealt the final blow to its rival by introducing the new racers’ category of indépendants. These ‘independents’ were racers who, although not yet professional, could openly receive money and sponsorships. Their introduction quickly drained the ranks of amateurism, which had in any case become purely theoretical: by 1911, most amateurs were de facto paid or sponsored. In the same year, the UBSSA ended its racing activities.[43]

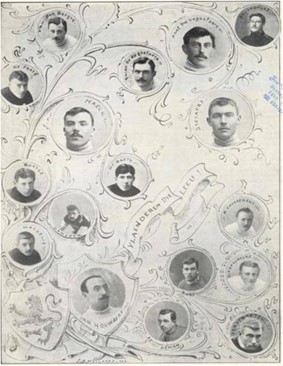

Figure 2

The Flemish racers Cyrille Van Hauwaert, ‘the revelation of Flemish cycling sport’, Jules Masselis and Abel De Vogelaere before 1914

Certainly the first one was a crucial figurehead of racing’s new momentum in Belgium during the late 1900s

Source:Wielermuseum, Roeselare

The popularity of this strongly professionalized racing also endowed it with a new social significance. Through their racing victories, young working class men like Van Hauwaert now became popular, wealthy public figures, making many times the average labourers’ wage. Not everyone, however, was pleased with the emergence of this new lower class hero. The powerful Catholic Church was highly critical of the sport’s new popular appeal, as it saw racing as making riders and spectators alike neglect their duties to family and faith and weakening their moral and physical health.[44] Those active in organizing and reporting on racing looked at things differently. Firm believers in sport as an agent of physical and moral improvement, they presented the new working-class racer as the protagonist of a decent, healthy form of recreation. To Karel van Wijnendaele for instance, editor-in-chief and most influential pen of Sportwereld, racing could teach the masses essential social values, as the courage and willpower racers showed while fighting against nature, fatigue and rivals were essential to all those wanting to progress in life. Here, racers became examples of social mobility, able to uplift the masses and shape their ‘civic qualities’, an idea also present in papers like Vélo-Sport. Certainly, Van Hauwaert was often presented as exemplary. Such a presentation of racers, however, was also strongly paternalist. Its promoters were often convinced that the lower class racer was not to be trusted with shaping his own occupation, but needed the guidance of socially higher-ranking figures. Perhaps this distrust was sometimes justified, as racers’ behaviour was often far from exemplary. Critical press reports abound of racers wearing dirty clothes, swearing and even fighting on and off their bikes, thus endangering their exemplary role.[45]

Cycling and the ‘Flemish question’

Not only did the lower class background of the new generation of racers lead to considerable scepticism of their social role and impact. As the bicycle’s democratization brought new social groups to the vehicle’s consumption – whether for racing or leisure – Belgium’s growing ethno-linguistic tensions increasingly came to weigh on cycling as well. While the ‘Flemish movement’ had become a cultural and political mass movement in the 1890s and incessantly campaigned for the recognition of Dutch as an official language in the administration, army and judiciary, Belgian cycling had remained predominantly francophone. Even in Flanders, most cyclists belonged to the francophone bourgeoisie. Dutch-language cycling periodicals were few, as were Dutch-speaking clubs.[46] The bicycle’s democratization not only caused changes in the social background of the growing number of cyclists, but also a shift in their regional distribution. While the 1890s saw provinces with a lot of industry or major cities like Brabant and Antwerp having the most bicycle users, this had changed by 1912. Populous but more agricultural provinces like East- and West-Flanders took the lead, while the country’s Flemish provinces now had the most cyclists.[47}

This convergence between changes in cyclists’ social and ethno-linguistic makeup was soon noticed by cycling’s national associations. In order to strengthen their dwindling membership numbers as well as to counter the growing discontent of the association’s increasing number of Flemish members with its predominantly francophone character, the LVB began to devote resources towards accommodating this new group. In particular, the publishing of a new, Dutch-language periodical for Flemish cyclists, which would exist next to the francophone Revue Vélocipédique Belge, was given prominence. In 1897, the Antwerp-based cycling journalist Arthur Rotsaert had called for such a journal. Conspicuously denying he supported the Flemish movement, Rotsaert claimed it would promote national unity and strengthen the association by providing cyclists of both language groups with news of its activities.[48] While received with enthusiasm, the project soon faced difficulties. Although the LVB put in considerable efforts, the Dutch-language periodical which rolled off the presses in early 1899 was stillborn.[49]

As a consequence the LVB, which now also increasingly presented itself under its Dutch name of Belgische Wielrijdersbond, shifted its focus to establishing a Dutch-language section in its francophone Revue. Again problems surfaced, as articles in the section were mostly translated French ones, and were hardly read.[50] The Revue‘s Flemish section, too, soon disintegrated. In November 1901, the LVB/BWB, strapped for cash, cancelled all subsidies for the project. It would take until 1907, when the association again published its own periodical, for another Dutch section to appear. Even the latter struggled to survive.[51] Although all this coincided with the successful campaign of the Flemish movement for the ‘Gelijkheidswet’ (Equality law), which passed Parliament in 1898 and granted Dutch the status of an official state language, in the LVB/BWB Flemings failed to successfully form a critical mass. The association was not the only one investing in the growing group of Dutch-speaking cyclists. In November 1907, the TCB also decided to publish a separate Dutch-language periodical. Here as well, the initiative was presented as a way of better integrating Flemings into the Belgian association. The journal was equally unsuccessful. Attracting few subscribers, it ceased publication in December 1909. Despite both associations’ good intentions, TCB and LVB/BWB remained dominated by a francophone bourgeoisie.[52]

From the later 1900s onwards however, the growing prevalence of Dutch-speaking Flemings in cycling did begin to take effect. This was nowhere more evident than in racing. From the catalytic victories of Van Hauwaert onwards it was Flemish racers who had a strong share in Belgium’s international cycling successes. This, of course, did not mean Belgium’s francophone population was devoid of good racers but it was the Flemish riders’ growing prowess that made heads turn. Not only francophone journalists remarked on the exceptional popularity of racing in Flanders, especially in West- and East-Flanders.[53] Certainly in the booming Dutch-language sport press, the growing Flemish share within the sport was given attention. New periodicals like Onze Kampioenen (1909) proudly claimed how ‘Flanders has more ‘famous pedal kings’ than all other provinces of Belgium taken together.’[54] This growing Flemish sporting pride was not surprising: indeed, the very establishment of Dutch-language sporting titles in these years was often presented as a wilful act of Flemish consciousness by their founders. Now, the argument went, Flemings could enjoy sport news in their own language.[55]

Lions on Flemish soil

From its founding in September 1912, Sportwereld became the most consistent promoter of this discourse of Flemish cycling pride. Indeed, the title’s pro-Flemish sympathies were already reflected in its yellow paper and black lettering – the Flemish flag’s colors. These leanings were personified by its most prolific contributors, who all exhibited a significant degree of pro-Flemish sympathies. Karel Van Wijnendaele (a pseudonym of Karel Steyaert) already wrote articles for titles like Onze Kampioenen or Sportvriend in which he conspicuously celebrated Flemish racers’ successes before joining Sportwereld. Moreover, he was closely involved with the broader political and cultural Flemish movement.[56] The fact that many internationally successful Belgian racers hailed from Flanders offered Sportwereld a powerful vantage point for translating their pro-Flemish sentiments into a discourse that presented these racers as figureheads of a distinctly Flemish sporting prowess. Cyrille Van Hauwaert played a symbolic role here. His victories soon gained him a reputation throughout Belgium as the main pioneer of racing’s new momentum. In reporting on him, early Flemish sport papers like Sportvriend focused on his Flemish background. In fact, one of Karel van Wijnendaele’s first full-length articles, published in 1909 in the illustrated periodical Onze Kampioenen, was a lengthy interview with Van Hauwaert in which he presented the latter as the ‘Lion of Flanders’, a strong, healthy and ‘untameable’ figure. Van Wijnendaele was not the first to use this nickname for van Hauwaert, which – paradoxically – was first coined by French sports journalists. However, as it referred to both the lion on the Flemish flag and to iconic Flemish writer Hendrik Conscience’s popular novel (1838) on the Battle of the Spurs of 11 July 1302, both powerful cultural symbols of the Flemish movement, the nickname closely associated Van Hauwaert with Flanders, its history and its people.[57]

The first to defeat the French riders on their own turf, van Hauwaert became the first link in a ‘genealogy’ of exceptional Flemish riders Sportwereld now began to construct, in which contemporaries of him were hailed as his successors or even, like 1912 Tour de France-winner Odiel Defraeye, as ‘the son of the Lion of Flanders’.[58] Thanks to his good performance in the 1913 Tour de France, Marcel Buysse became popular as the new symbol of Flemish cycling in the years before the war, being described as a daring, no-nonsense rider full of ‘Flemish life and uncomplicated beauty’, ‘the true Lion of Flanders’.[59] As distinctly Flemish cycling heroes, Sportwereld also imagined these riders as having a distinct riding style and sportive character. In describing Van Hauwaert’s victory in the 1909 national championships, Onze Kampioenen prominently used characteristics like physical strength, courage and perseverance.[60] Especially in reports of races plagued by bad roads, steeps climbs or extreme weather these values were placed centre stage, with the riders winning or simply ‘surviving’ these events presented as true examples of courage and perseverance.[61] Such racing events were presented as vehicles for discovering the sport’s real champions, as human strength and willpower really showed itself in all-out battle with nature.

To be sure, courage and perseverance, strength and willpower were qualities also used by other sports papers to describe riders, whether Flemish, Belgian or foreign, as they were constituent of the heroic and ‘manly’ masculinity which racing was seen to promote.[62] In Sportwereld however, they were seen to apply especially to Flemish racers, who thus personified the qualities of the Flemish people as a whole. The paper often linked the power and courage they saw ‘their’ racers as exhibiting to the image of the tough, stubborn Fleming prominent in broader Flemish cultural discourse. Like many of their Flemish lower class peers, racers were imagined as being of a simple, rough but ‘authentic’ upbringing, a precondition for their mental and physical aptitude for their sport.

Intimately connected to such ideas was the attention the journal paid to the rural background of many riders. In his 1909 interview with Van Hauwaert, Van Wijnendaele convoluted the latter’s strength and willpower with his simple and healthy life in a West-Flemish rural village, a connection later made in reports on many other Flemish riders. Again, this tied into broader sentiments: since the nineteenth century, Flanders’ rural population was imagined as an inherently positive social force by many in pro-Flemish circles. Despite the region’s strong historical urbanization, it was the quiet countryside and its small-time farmers – poor but healthy, strong and devotedly Catholic – that represented the quintessence of Flemishness. ‘Peasant’ became a name of honour, denoting a ‘real’ Fleming and his qualities.[63]

Figure 3

Constructing Flemish racing genealogies: a tree of Flemish ‘lions’ with Van Hauwaert as its root in Onze Kampioenen, 1909

Source:Sportimonium, Hofstade

Sportwereld‘s imagining of Flemish racers as personifications of all that was good in the Flemish people served a clear purpose. Van Wijnendaele expressed this best in a 1913 article on Odiel Defraeye:

while our Flemish foremen go forward with closed ranks for the rebirth of our Flanders…we have our riders showing the people how, from a physical point of view, we are not staying behind either, who show the people that humble Flanders has great men![64]

Infatuated with the idea of a Flemish ‘rebirth’, the effect these riders could have on Flemings’ morale and self-consciousness was crucial to him: just like the Flemish movement, they could make the latter aware of their own strength in a country where they were an underdeveloped, suppressed minority. As some of his articles suggest, Van Wijnendaele was influenced by the ideas of Flemish intellectual Lodewijk de Raet, who saw the development of the Flemish ‘volkskracht’ (people’s force) – its mental and physical capabilities – as a road to building a strong, prosperous Flanders. Inspiring the people through the performances of ‘their’ Flemish racers, then, could stimulate this ‘volkskracht’.[65]

Seen from this perspective, the races Sportwereld organized equally played an important role in realizing this goal. The Tour of Flanders (‘De Ronde van Vlaanderen’), first organized in May 1913 by the paper’s director Léon van den Haute, passed through West- and East-Flanders, racing’s Flemish heartland. Its founding was clearly inspired by the Tour de France and its strongly nationalist formula – as were many other ‘national Tours’ set up in Europe during these decades.[66] Aimed at bringing together Flanders’ successful racers in their own region, Sportwereld saw the event as unifying the Flemish soil, its people and its racers. Indeed, the spatial features of the event played a crucial role in its imagination. To Van Wijnendaele in 1913, its trajectory constituted the essence of Flemish culture and history.[67] The race was described as a succession of Flanders’ different regions and cities. In the case of the latter, their ‘glorious’ medieval past was strongly emphasized, with Van Wijnendaele invoking the memory of medieval heroes of Ghent (the race’s starting place) like Jacob Van Artevelde. As such, the event was indirectly used to teach the paper’s readers something about Flanders’ historical greatness.[68] The Flemish riders competing in the Tour, in their turn, were intimately linked to the territory the event passed through by, for instance, consistently stressing how the former put in extra effort when passing through their home region. In 1914, Marcel Buysse was described as vigorously taking the lead when the race passed through his home town, where many had come out to watch him. As such, the Flemish soil itself became one of the race’s constituent elements, acting in synergy with the racers themselves. Indeed, its long distance and the badly cobblestoned roads of Flanders were presented as making it a tough challenge, in which only strong Flemings could prevail.[69]

As propagators of this discourse, Sportwereld‘s contributors (and especially Van Wijnendaele) can be characterized as so-called ‘cultural flamingants’, pro-Flemish militants who – sometimes in an outright paternalist way – attempted to ‘better’ the Flemish masses by educating them on their own culture, history and possibilities. In 1913, Van Wijnendaele called the Sportwereld-staff ‘workers for the intellectual development of our people, labourers on the mental field of Flemish Belgium’.[70] The parallels with the earlier-mentioned discourse of Van Wijnendaele on the social exemplarity of lower class racers like Van Hauwaert are evident. By offering examples of uplifting social behaviour, these personalities would not only better integrate the masses into Belgian society, but also create a stronger Flemish people. Such a discourse, which coupled an appreciation for the social potential of the Flemish working classes to demands for their emancipation would increasingly strike a chord with the Flemish public, as the interwar period would show. Indeed, the growing success of the Christian workers’ movement in Flanders during these decades was in part based on a similar discourse, which, at the same time, made a moderate kind of political pro-Flemishness acceptable to increasing parts of the public.[71]

Flemish pride, Belgian loyalty?

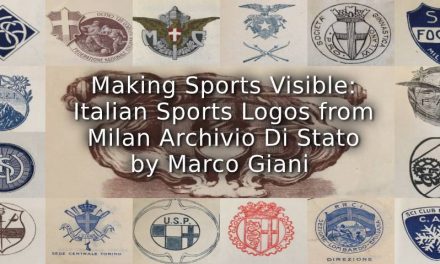

In spite of Van Wijnendaele and his Sportwereld colleagues continuously professed Flemish identity, theirs was not an endeavour which was directed against the reality of the Belgian state, nor against the idea of there also being a distinct Belgian nation. Indeed, while a Flemish identity was given increasing substance in the Dutch-language sports press, this did not mean that sentiments of Belgian nationalist pride of the success of the country’s racers were absent from the sport. The LVB/BWB, for one, was still a staunchly nationalist organization, a stance which was reflected by the articles it dedicated to Belgian international racing victories in its periodical. While a discourse celebrating the specific strengths and characteristics of Belgium’s French-speaking, ‘Walloon’ racers was also increasingly present here, the country’s francophone sports press were characterized by a similar Belgian nationalism.[72] This was especially evident in the latter’s reporting on the Tour of Belgium. This Tour for professionals, first organized by the francophone daily La Dernière Heure in 1908, not only evoked the idea of a unified Belgian nation in its name. Here as well, its very trajectory presented ‘Belgium’ as a meaningful entity, uniting all of the country’s cities and provinces and featuring riders from its regions. Reports informed readers on the history, geography and aesthetic qualities of all parts of Belgium and how they, as ‘petites patries’, together made up the ‘grande patrie’ of the nation.[73] Described in terms like the ‘grand national race’ in LDH and Vélo-Sport, the event was seen to unite young and old. As such, the Tour of Belgium was imagined as a ‘unifier, regenerator and educator’ similar to the Tour of Flanders, bringing together the nation in admiration for the prowess of its sporting representatives. As generators of ‘national energies’, they dispensed their moral and physical qualities to those along the race’s trajectory, benefiting the nation as a whole.[74]

Although never forgetting to pay special attention to the prowess of Flemish racers competing in the event, more often than not Sportwereld joined such celebrations of Belgian pride in its reporting on the Tour of Belgium.[75] Like most associated with, or sympathetic to, the pre-war Flemish movement, Van Wijnendaele and his colleagues still believed that Flanders and Belgium were complementary or interlocking forms of ‘national’ identity, with the former eventually being subsidiary to the latter. Van Wijnendaele’s writings were also regularly filled with statements like ‘Fleming or Walloon, we’re all Belgians’, while racers were often celebrated as both Belgian and Flemish in the same articles.[76] Indeed, in the case of the Tour de France it was especially the rivalry between French and Belgian riders which was given attention in both the Flemish and the francophone press, sweeping aside the one between Flemings and Walloons. Here, both groups were seen to cooperate harmoniously, complementing each other in a common quest for Belgian victory. Sportwereld, for instance, put the Belgian flag first in its Tour report of 1913, claiming how ‘Fleming and Walloons march hand in hand [behind it] … brothers of the same blood, children of the same country.’[77]

Figure 4

A web across the nation: the trajectory of the first Tour of Belgium for professionals in 1908

Source:La Dernière Heure

Epilogue

The outbreak of war in 1914 brought the whole dynamic I have just outlined to a standstill. Under the strict German occupation, both the LVB/BWB and TCB ceased almost all activity.[78] While road racing was made virtually impossible, cycling tracks in cities such as Brussels or Ghent did organize races in the early war years. Even the bicycle’s everyday use was severely hampered, especially when the German Army began to requisition bicycles and rubber tyres in late 1916.[79] After the Armistice, however, cycling in all its forms witnessed a rapid revival. By 1919, Belgian riders were again conspicuously present in international track and road racing, and the number of events in the country itself soon reached a new high. Together with football, cycling became Belgium’s most popular sport of the Interbellum. During these interwar years, its potential as a mass sport was fully realized. This evolution, however, was also accompanied by new discussions about the social role of working class racers and, especially, a new prominence of the sport as a vehicle for Belgian and Flemish identity. The discourse on racing as a symbol of Flemish identity was now given greater prominence. This discourse also became increasingly radical at times, as a growing number of pro-Flemish militants became full-fledged Flemish-nationalists during the interwar years, striving for Flemish independence from the Belgian state. The Great War thus did not entail a radical rupture with what came before. Rather, it brought developments that were ongoing to a temporary halt. After 1918 they were resumed, albeit at a faster pace. In this sense, the shock of the war did have its effects. At least in the field of cycling, Belgium was characterized by a dynamic similar to the one that George Dangerfield identified in Great Britain’s social and political history of the immediate postwar period: ‘The War hastened everything…but it started nothing’.[80]

References

[1] Stijn Knuts, Converging and Competing Courses of Identity Construction: Shaping and Imagining Society through Cycling and Bicycle Racing in Belgium before World War Two (unpublished PhD Dissertation, KU Leuven 2014), 13-14.

[2] Bart Vanreusel, ‘Sport en culturele identiteit: de wielerwedstrijd Ronde van Vlaanderen’, in Sportsociologie. Het spel en de spelers, eds. Paul De Knop et. al., 2nd Ed. (Maarssen: Elsevier, 2006), 432-437.

[3] Sophie De Schaepdrijver, De Groote Oorlog: het koninkrijk België tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (Antwerp: Houtekiet, 2014).

[4] Gita Deneckere, 1900: België op het breukvlak van twee eeuwen (Tielt: Lannoo, 2006); Guy Vanthemsche, Belgium and the Congo, 1885-1980 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012); Eric Min, De eeuw van Brussel: biografie van een wereldstad 1850-1914 (Antwerp: Bezige Bij, 2013); Daniel Laqua, The Age of Internationalism and Belgium, 1880-1930: Peace, Progress and Prestige (Manchester: University Press, 2013).

[5] Deneckere, 1900 and Michel Dumoulin, ‘Het ontluiken van de twintigste eeuw, 1905-1918’, in Nieuwe geschiedenis van België. II: 1905-1950, eds. Dumoulin, Emmanuel Gerard, Marc Van Den Wijngaert and Vincent Dujardin (Tielt: Lannoo, 2006), 697-868.

[6] Nationalism in Belgium: Shifting Identities, 1780-1995, eds. Kas Deprez and Louis Vos (Basingstoke: MacMillan, 1998); Bruno De Wever, ‘The Flemish movement and Flemish nationalism. Instruments, historiography and debates’, Studies on National Movements 1 (2013): 50-80.

[7] Andrew Ritchie, Quest for Speed: A History of Early Bicycle Racing, 1868-1903 (El Cerrito 2011), 29-32; Francis Lauters, Les Débuts du Cyclisme en Belgique (Brussels 1936), 30-43.

[8] Le Véloce, February 22, 1895; Ruben Mattheus, De interne geschiedenis van de Koninklijke Belgische Wielrijdersbond, de Union Cycliste Internationale en haar Belgische voorzitters (1882-1922) (unpublished Lic. dissertation, KU Leuven 2005), 115-142; Lauters, Les débuts, 17-23.

[9] Revue Vélocipédique Belge, April 15, 1889, 37; Lauters, Les débuts, 58-62 and 70-91.

[10] Ritchie, Quest, 225-238; Le Véloce, March 7, 1895; Cycliste Belge Illustré (CBI), 19 Oct. 1891.

[11] De Wielrijder, May 31, 1894, 546-547; RVB, August 26, 1897, 703.

[12] De Wielrijder, December 14, 1893, 362-363; Touring Club de Belgique. Bulletin Officiel (TCB), August 1895, 2-3; Christopher Thompson, ‘Un troisième sexe? Les bourgeoises et la bicyclette dans la France fin de siècle’, Le Mouvement Social 192/3 (2000): 9-40.

[13] CBI, July 18, 1895, 3385, TCB, June 1895, 2; Stijn Knuts and Pascal Delheye, ‘Connecting City and Countryside? Faces of Cycling Mobility in Belgium, 1890-1914’, Dutch Crossing 37 no. 3 (2013): 242-243.

[14] CBI, September 28, 1893, 1697-1698; Knuts and Delheye, ‘Borderless Sport? Imagining and Organising Bicycle Racing in Belgium, 1869-1914: Between Transnational Dynamics and National Aspirations’, European Review of History 21 no. 3 (2014): 383-387.

[15] RVB, June 14, 1894, 318-319; Organe de l’Union Vélocipédique Libre (UVL), November 8, 1893, 6-7.

[16] Knuts and Delheye, ‘Borderless Sport?’, 388-389.

[17] Catherine Bertho-Lavenir, La roue et le stylo: comment nous sommes devenus touristes (Paris 1999), 113-136; Lauters, Les débuts, 223-243.

[18] CBI, October 12, 1890, 2; November 14, 1895, 4293-94.

[19] CBI, January 31, 1895, 3234; February 21, 1895, 3317; February 28, 1895, 3342-43.

[20] Knuts and Delheye, ‘Cycling in the City? Belgian Cyclists Conquering Urban Spaces, 1860-1900’, International Journal of the History of Sport 29 no. 14 (2012): 1945-1948.

[21] De Wielrijder, August 23, 1894, 647-648; CBI, December 6, 1894, 3015; November 28, 1895, 4336.

[22] CBI, December 31, 1891, 47-51; RVB, September 27, 1894, 555-557; Knuts and Delheye, ‘Connecting’, 242-245.

[23] See f.i. CBI, October 11, 1894, 2863.

[24] CBI, October 10, 1895, 4178-79; TCB, March 1901, 59-60.

[25] RVB, August 2, 1891, 14; TCB, October 1900, 218-219; Lauters, Les débuts, 158; Knuts and Delheye, ‘Connecting’, 244.

[26] Donald Weber, Automobilisering en de overheid in België vóór 1940. (Unpublished Doct. Diss.: UGhent, 2008), 118-162 and 225-236.

[27] Nan Van Zutphen, ‘Sociale geschiedenis van het fietsen te Leuven, 1880-1900’, in: Arca Lovaniensis: Jaarboek vrienden stedelijke musea Leuven 8 (1979), 119-136; L’Illustration Sportive, June 15, 1911, 19; De Wielrijder. Tolk, December 1, 1909, 12; RVB, October 4, 1900, 730-731.

[28] Knuts en Delheye, ‘Borderless Sport?’, 394-396.

[29] TCB, December 1900, 266; July 15, 1909, 289.

[30] RVB, November 21, 1901, 746-751; February 13, 1902, 104-107; L’Automobile-Véloce, December 15, 1904, 9-11.

[31] Le Sportsman, March 24, 1906, 3-4.

[32] De Wielrijder. Tolk, July 15, 1912, 1-9; Maandschrift van den Belgischen Touring Club, February 15, 1908, 28.

[33] Knuts and Delheye, ‘Connecting’.

[34] RVB, March 3, 1898, 147; Le Sportsman, January 1905, 5-7.

[35] Bruno Schalembier, Historiek van het voetbal in België tot de Eerste Wereldoorlog (unpub. Lic. Diss., UGhent 1998); La Vie Sportive, June 14, 1905, 2; January 10 and 14, 1907, 1; January 2, 1908, 1; January, 13, 1910, 1; Le Sportsman, August 8, 1906, 3; Bulletin Officiel Mensuel de la LVB (BOM), April 1907, 13.

[36] Le Véloce, July 8, 1896, 2; RVB, May 31, 1894, 279; Filip Bastiaen, ‘Volkscultuur of sport? Velospelen in het Meetjesland, 1892-1896’, Tijd-Schrift 4/3 (2001): 16-33.

[37] CBI, October 18, 1898, 7312; October 20, 1898, 7320-7321; RVB, December 20, 1900, 934-935.

[38] Cited in W. Hamerlynck, ‘Over Vincent Reychlern, een Eeklose “coureur”’, Ons Meetjesland 11 no. 2 (1978).

[39] RVB, June 16, 1898, 391-392; October 27, 1898, 695-696; Bruges, State Archives, Archive of Steenkerke, nr. 2455.

[40] Dries Vanysacker, Vlaamse Wielerkoppen (Leuven: Davidsfonds, 2011), 68-82; Knuts, Delheye and Vanysacker, ‘Wentelende Wielen: anderhalve eeuw fietsen en wielrennen in Vlaanderen’, in Vlaanderen fietst! Sociaalwetenschappelijk onderzoek naar de fietssportmarkt, eds. Jeroen Scheerder, Wim Lagae and Filip Boen (Ghent: Academia Press, 2011), 32-36.

[41] Le Vélo changed its name to Vélo-Sport in 1911. Greta Vandevenne, Karel van Wynendaele (1882-1961), de pionier van de Vlaamse sportjournalistiek, en ’Sportwereld’ (1912-1939) (unpublished Lic. Dissertation, KU Leuven 1988), 57-69; François Gilbert, Le quotidien Les Sports: 1906-1977 (unpublished Lic. Dissertation, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 1990).

[42] Hugh Dauncey, French Cycling: A Social and Cultural History (Liverpool 2012), 45.

[43] BOM, March 1911, 34-38; La Vie Sportive, February 20, 1911, 1.

[44] De Onafhankelijke der Provincie Limburg, May 18, 1913, 1.

[45] Knuts and Delheye, ‘Sport, Work and the Professional Cyclist in Belgium, 1907–40’, History Workshop Journal 79 (2015): 154-176.

[46] Marijke Den Hollander, Sport in ‘t Stad: Antwerpen 1830-1914 (Leuven: University Press, 2006), 214-215; CBI, December 8, 1892, 799; June 20, 1895, 3741.

[47] LVB, October 18, 1925, 1-3.

[48] RVB, November 25, 1897, 942-944; December 30, 1897, 1040.

[49] B.W.B Belgisch Wielrijdersblad. Sport–Toerism–Automobiel, April 6, 1899.

[50] RVB, April 5, 1900, 221-223; November 8, 1900, 824; November 15, 1900, 837-839; November 22, 1900, 862-863.

[51] RVB, November 21, 1901, 737-738; BOM, January 1911, 11.

[52] TCB, December 30, 1907, 377; Maandschrift, February 15, 1908, 24; November 15, 1909, 161.

[53] Armand Varlez and P. Dupont, Nos Souvenirs du Tour de Belgique (Brussels: s.l., 1909) 23-25.

[54] Onze Kampioenen, November 1909, 124; January 1909, 3; April 1910, 1-4

[55] Het Sportblad, March 28, 1908, 1.

[56] Vandevenne, Karel, 41-72 and 273.

[57] The Battle of the Spurs saw a Flemish army defeat the much stronger forces of the French king. Frederik Backelandt, Patrick Cornillie and Rik Vanwalleghem, Koarle! De man die zijn volk leerde koersen: Karel Van Wijnendaele. Balegem-Tielt: Pinguin Productions, 2006), 16-20; Onze Kampioenen, January 1909, 9-11; Sport-Echo, May 20, 1911; Sportwereld, June 20, 1913, 2.

[58] Sportwereld, April 15, 1914; Onze Kampioenen, April 1909, 43; Knuts and Delheye, ‘Identiteiten in koers. Roeselaarse wielrenners als kopmannen van lokale, regionale en (sub)nationale identiteiten, 1900-1960’, Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Nieuwste Geschiedenis 41 nos. 1-2 (2011), 167-214; Sportvriend, July 17, 1912, 1-2.

[59] Sportwereld, May 5, 1913; March 13, 1914.

[60] Onze Kampioenen, September 1909, 94-95.

[61] LDH, May 6, 1913, 1-2.

[62] Compare with Thompson, The Tour de France: A Cultural History (Berkeley: University Press, 2006), 12 and 96-107.

[63] Compare with Henk De Smaele, Rechts Vlaanderen. Religie en stemgedrag in negentiende-eeuws België (Leuven: Universitaire Pers, 2009).

[64] Sportwereld, April 4, 1913.

[65] Sportwereld, July 29, 1914; Filip Boudrez, ‘Raet, Lodewijk de’, In: Nieuwe Encyclopedie van de Vlaamse Beweging, vol. III (Tielt: Lannoo, 1998), 2530-2534.

[66] Sportwereld, May 16, 1913, 1; Anthony Cardoza, ‘’Making Italians’? Cycling and National Identity in Italy: 1900-1950’, Journal of Modern Italian Studies 15 no. 3 (2010): 354-377; Jean-Luc Bœuf and Yves Léonard, La république du tour de France (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2003), 64-65.

[67] Sportwereld, May 21, 1913.

[68] Sportwereld, March 25, 1914.

[69] Sportwereld, March 23, 1914; March 27, 1914; Vanwalleghem, Het Wonder van Vlaanderen. Het epos van de Ronde (Ghent: Pinguin, 1998), 34-43.

[70] Backelandt, Ons rijke Vlaamse wielerleven en het wielerflamingantisme: ‘Sportwereld’ als gangmaker van identiteit in het interbellum (Unpublished Ma. Dissertation: UGhent, 2004), 52-57; Sportwereld, September 12, 1913, 1.

[71] Lode Wils, ‘De historische verstrengeling tussen de christelijke arbeidersbeweging en de Vlaamse beweging’, in Emmanuel Gerard and Jozef Mampuys eds., Voor kerk en werk. Opstellen over de geschiedenis van de christelijke arbeidersbeweging, 1886-1986 (Leuven: University Press, 1986), 15-40.

[72] Knuts, Converging, 284-285; LVB, July 1912, 113-116.

[73] Vélo-Sport, August 20, 1911; August 26, 1911; LVB, July 20, 1932, 5; Thompson, The Tour, 58.

[74] Bœuf and Léonard, La république 52-56 and 67-75; LDH, May 27, 28 and 29, 1908; May 21, 1911.

[75] Sportwereld, May 5, 1913, 1.

[76] Onze Kampioenen, July 27, 1912.

[77] LDH, July 16, 1914, 1-2; Sportwereld, June 27, 1913.

[78] LVB, January 1921, 1; Vélo-Sport, November 16, 1918, 2; March 6, 1919, 1.

[79] Knuts, ‘Koersen in magere tijden. Wielrennen in bezet België tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog’, Etappe. Magazine over historische fietshelden, no. 3 (2014): 16-22.

[80] George Dangerfield, The Strange Death of Liberal England (1910-1914) (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2011), originally published in 1935, xiv.