By the early summer of 1916, Captain Gilbert Laird Jessop (hero of the 1902 Oval Test Match) was suffering from severe lumbago. He was sent by his regimental Doctor to Bath, for ‘Radiant Heat Treatment’, where the patient was lowered into a coffin-like apparatus and the entire contraption was then steamed up with only the head remaining visible, experiencing temperatures of up to 150 degrees celsius. [The Edwardian steam-bath had become very popular in America and had been pioneered by Dr Kellog at his Battle Creek Sanatorium in Michigan.] However, when Jessop entered the box, the catch accidentally fell, trapping him inside. The attendant had left the room, so he was literally left to broil for over half an hour!

The Edwardian Steam Bath

By kind permission of The Royal Institute

When he was eventually rescued, his heart had undergone permanent damage and the sporting career of this great athlete had come to an end. He was just 42, but he would never play any form of cricket again.

What eventually turned out to be his last match, had taken place ten months earlier and was reported in The Tamworth Herald on the 4 September 1915:

‘Cricket at Drayton Manor- An Excellent Match’.

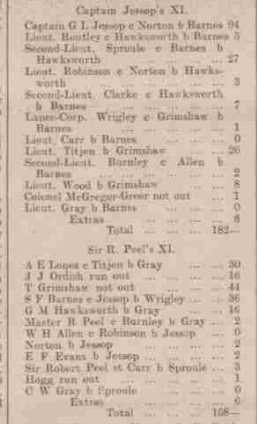

‘A match was played between a Brigade team and a team captained by Sir Robert Peel in aid of The British Red cross. However, the feature of the Brigade innings was the brilliant display of the free hitting by Captain G.L. Jessop who’, reported The Herald, ‘contributed 94, which included eight 4’s and seven 6’s. He was only at the crease for 45 minutes, but he punished the bowling severely’

Scorecard from Jessop’s final match

Source: Tamworth Herald Saturday 04 September 1915

Jessop recalled that in the opposing team was the ex-England fast bowler S.F. Barnes.

‘Peel got six county players including Barnes. We got 182 and they got 158, so we beat ’em. I got 94, most of ’em off my nose, for Barnes was pretty nasty on a rough-ish pitch’.

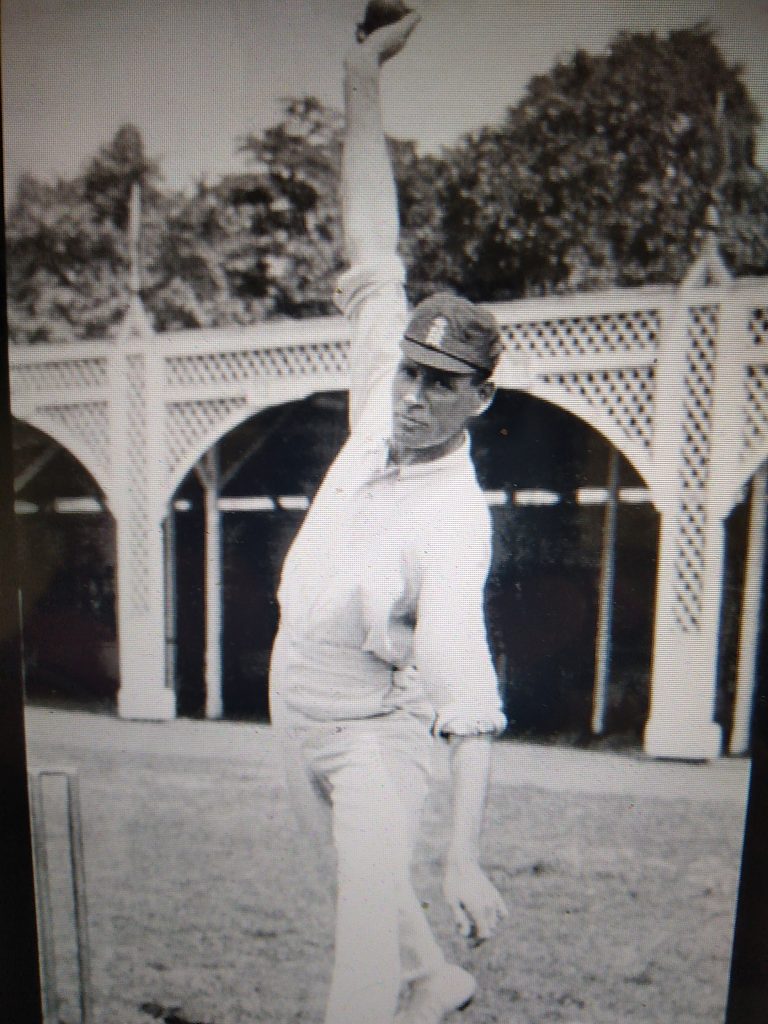

Barnes was regarded as one of the greatest bowlers of all time. He bowled at pace with the ability to make the ball swing and break from off to leg and took 189 wickets during his career, at an average of 16.43. At the point when this match was played, Barnes was no longer playing test cricket (his last match was a year earlier in 1914 against South Africa) but was still playing for Staffordshire. Barnes had famously taken 49 wickets in the first four tests against South Africa in 1913/14 but refused to play in the final test because the MCC failed to pay his wife’s hotel bill.

S.F.Barnes- one of the greatest bowlers England has ever produced

Source: Author’s collection

As a result, England discarded him despite being arguably the best bowler ever produced in this country. When in 2018, Jimmy Anderson surpassed 900 points, it was noted that sitting at the top of the ‘ICC All-Time’ list was none other than Sydney Barnes with 932. (A bowler gains points based on wickets taken, runs conceded and match result, with more points gained for dismissing highly rated batsmen). Jessop and Barnes knew each other well having played together on seven occasions for England, the most recent of which had been in the 1st and 2nd tests against South Africa in 1912.

The onset of War had brought to an end ‘The Golden Age of Cricket’, but Jessop seemed initially unwilling to finish his first-class career and played in nine matches for Gloucestershire in 1914 and for ‘The Gentlemen’ against ‘The Players’ at both Lord’s and The Oval. However, the outbreak of war ended his career unexpectedly. He decided not to play any more county cricket and although he didn’t know it, when he walked off the Bristol Ground on the afternoon of August 4th, 1914, he had played his last first-class match.

Jessop’s contribution in the one wicket victory over Somerset, was disappointing with the bat (25 and 4), but much more impressive with the ball (4-34 and 1 for 7), but it was undoubtedly the bowling performance of the future England all-rounder, J.C. ‘Jack’ White, that would have caught the eye, taking 9-48 and 5-32 respectively. White went on to play in 15 tests and was named ‘Wisden Cricketer of the Year’ in 1929.

J.H.’Jack’ White, who took 13 wickets for Somerset in Jessop’s final first-class match

Source Author’s collection

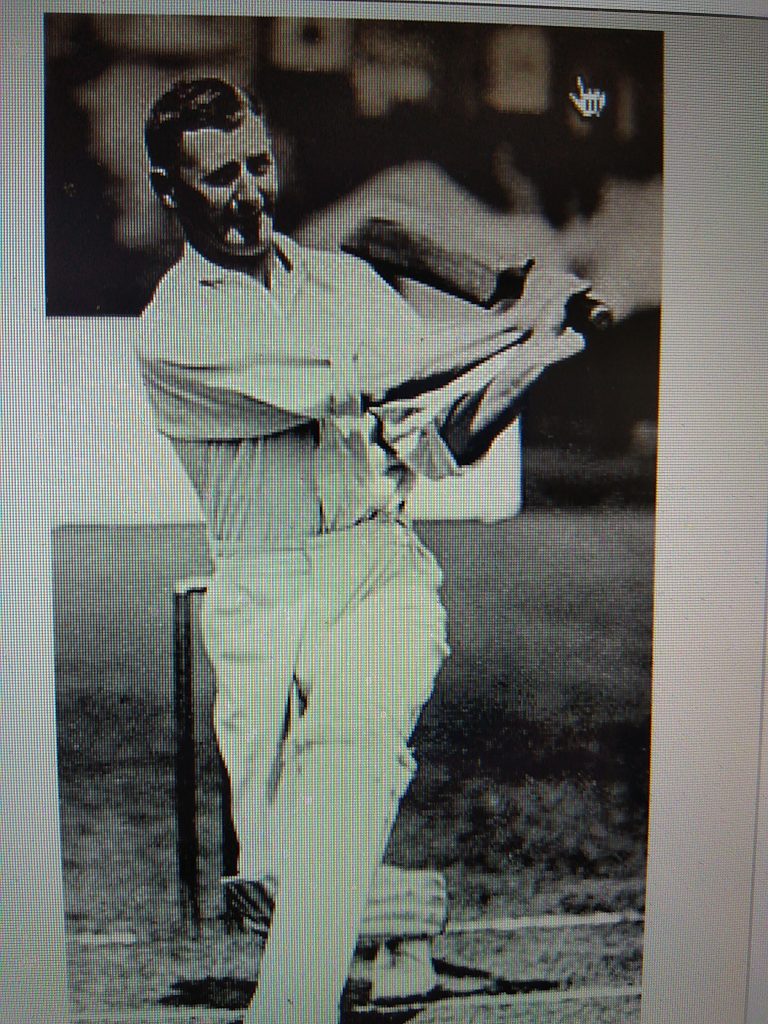

Counties actively encouraged their players to enlist so, in December 1914, Jessop was commissioned as a Captain in the 14th Manchester Regiment and the following summer he took part in a very successful recruiting campaign alongside A.C. McLaren (who had captained England at various times between 1898 and 1909), where they were successful in encouraging over 700 men to join up. The persistence of counties in pushing players to enlist demonstrated that they were very aware of their role in assisting the war effort. The spread of county cricket had made the game truly national, and no other sport could claim the same level of popular appeal cutting across all social boundaries.

As the war progressed, Britain looked toward the ‘National Game’ for support and cricketers of all abilities and backgrounds rushed to enlist and set the right example. When War was declared in August, the cricket authorities at first intended for the season to continue, however the mood of the country changed within weeks, and it was considered ‘immoral’ for young men to be playing cricket while their contemporaries were fighting in Europe.

Jessop during his recruitment drive

By kind permission of Roger Gibbons

In July 1914, Dr W.G. Grace, aged 64, played his penultimate game of cricket, scoring 69 at Eltham. He played one more match but did not bat or bowl; his heart was no longer in cricket and by the end of August he could bear it no longer and wrote to ‘The Sportsman’ magazine encouraging players to join up.

‘I should like to see all first-class cricketers of suitable age set a good example and come to the help of their country without delay in its hour of need’,

…implored the Doctor (over 200 first class cricketers are known to have joined up, of whom 34 were killed). The man known to many as, ‘The Father of Cricket and who had first played for England in 1880, was to pass away the following year.

Following the incident in the steam bath, Jessop re-joined his regiment, but it soon became apparent that his heart had been severely damaged and was unfortunately invalided out of the Army in 1917. During his first-class career [including tests] he had scored 27,267 runs, which included 54 centuries, 883 wickets and 473 catches in a career lasting over 20 years! He scored at around 80 runs per hour compared with Bradman who scored 47. He was without question, ‘A true All-Rounder’. One hundred and twenty years after the event, he still holds the record for the fastest century (76 balls ) by an Englishman in a Test Match.

Jessop scored six centuries playing, ‘Army Cricket’

Source Author’s collection

He made his living as an outspoken cricket journalist for the next 39 years and died in 1955 at the age of 80. Amongst the many tributes paid to Gilbert Jessop, one stands out:

‘He was undoubtedly the most consistently fast scorer I have seen. He was a big hitter too and it was difficult to bowl a ball from which he could not score. He made me glad that I was not a bowler. Gilbert Jessop certainly drew the crowds too, even more than Bradman I should say’

Sir Jack Hobbs (England Batsman 1908- 1930)

Sir Jack Hobbs

Source Author’s Collection