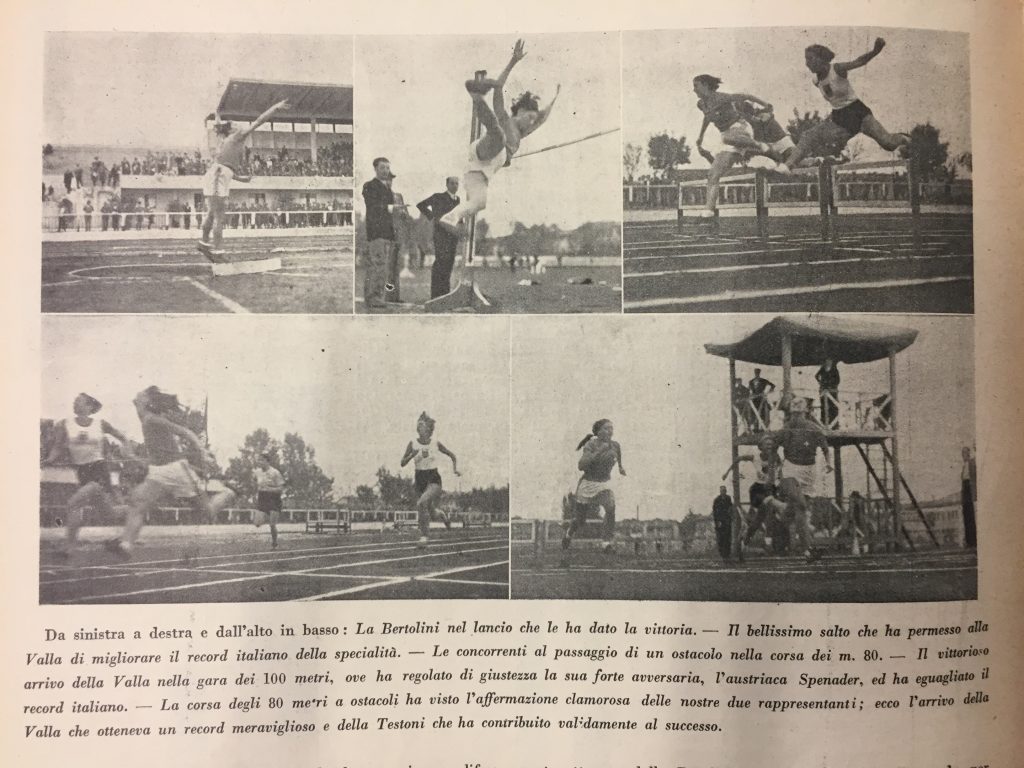

Talking about the recent campaign for the reintroduction of the bodysuit by the Australia basketball team, Felicity Smith underlined that, although it was a controversial decision (someone claimed that ‘the switch to tighter fitting suits for the women’s team alone could be seen as exclusionary’), it was taken not by Federation but by the players themselves, the same one who had chosen to remove bodysuits in 2008 (see https://sirensport.com.au/op-ed/uniforms-have-more-meaning-than-what-we-wear/ ). Did Italian athletes had any kind of control over their sports uniforms in 1920s’ Italy? Did they played any role in that fashion anarchy? We don’t know. What we do know is that that anarchy was going to end, as with any kind of social freedom in Fascist Italy, a country where the regime was slowly turning everything towards some ideological goal. Because of the 1928 controversy between the Church and the regime on the occasion of the Concorso ginnico-atletico, about which there will be more discussion later in this article, the Italian Federation of Athletics (FIDAL) decided to have a clampdown: it defended the right of the athletes to compete in shorts, but it yielded to the pressure from the pro conservatives concerning what happened before and after the sporting events. In May 1932 FIDAL sent out a memo intimating the women’s athletes not to go outside the sporting arena unless they were wearing long trousers; while competing, the girls must not wear shorts that were too short, nor short-sleeved shirts. The first order wasn’t so speculative: some years before, the young Vittorina Vivenza was reported to the Bishop of Aosta for arriving at the stadium already dressed in her athletic shorts.

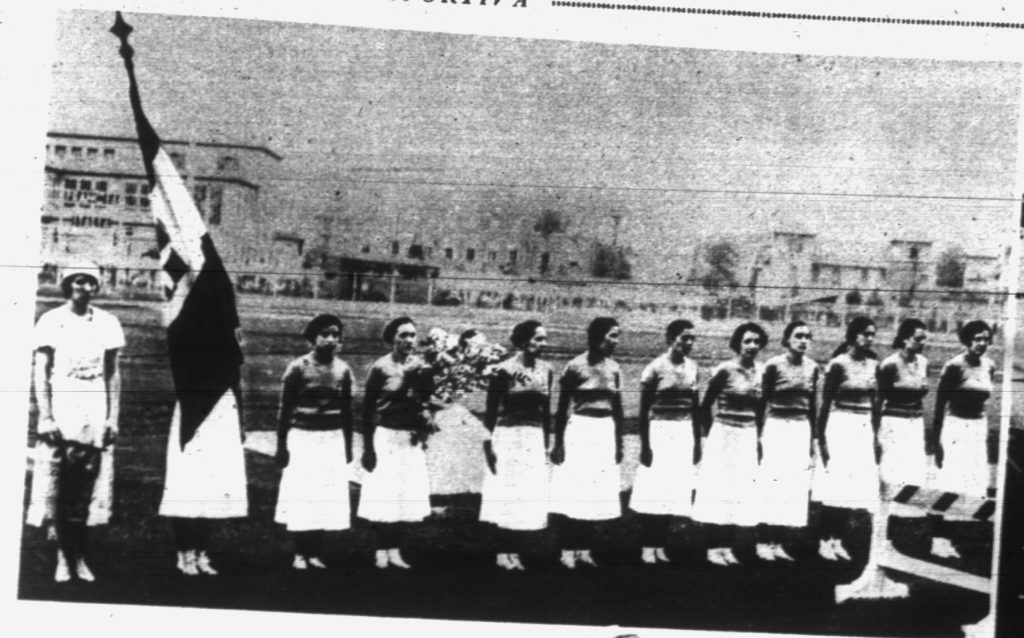

We can see this new policy in action as it were by viewing the photographs from the international meetings in which the Italian National Team competed. In 1933 Ondina Valla and her team-mates were still wearing the very long white skirts when they paraded on the pitch with the National flag; in 1934, they adopted long trousers, while their opponents were wearing shorts. It wasn’t until 1935 that the Italians decided to align their outfit.

Italian athletes before the Italy vs. France meeting (July 1933)

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 23/07/1933, p. 10

The greeting between the Italian and the French captain

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 23/07/1933, p. 10

Wien, [Vienna] September 1934: Austrian and Italian athletes before the international meeting

The Italians from centre to right: Bruna Bertolini; Fernanda Bullano; Livia Michiels; Piera Borsani; Maria Cosselli; Claudia Testoni; Ondina Valla

Source: https://bit.ly/3xh4ANO

Piacenza, June 1935: Italy National team before the international meeting vs. France

Source: Atletica, July 1935, p. 11

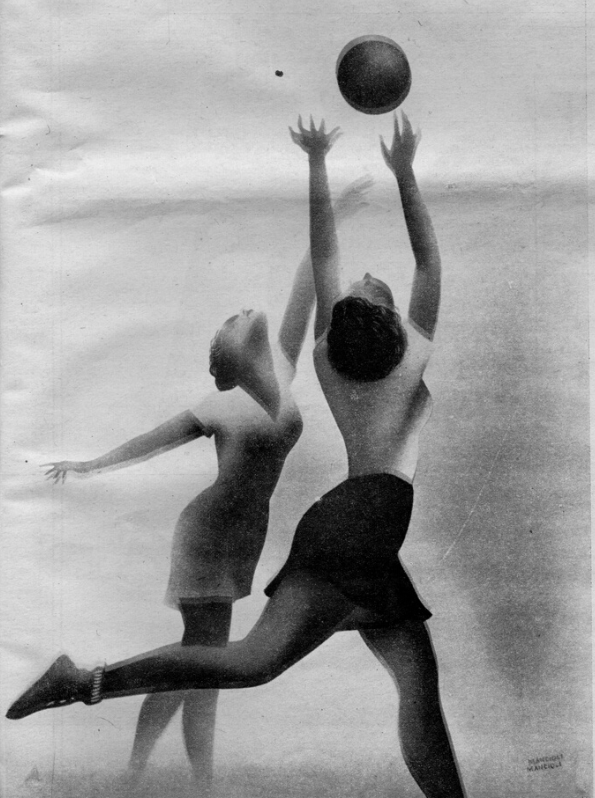

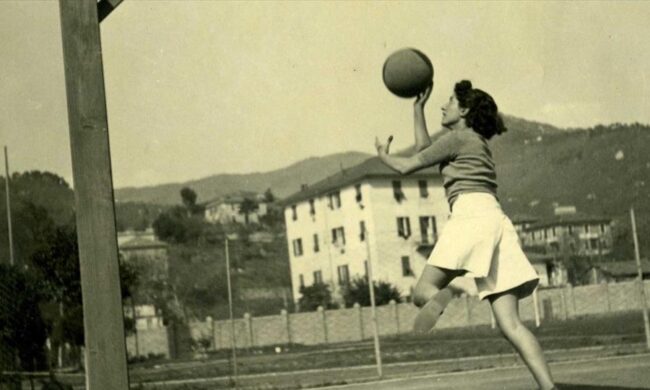

The first-ever Italian women’s basketball team was founded in Siena, in 1907, by PE teacher Ida Nomi Pesciolini: but it didn’t pull the trigger on the birth of a national movement, which only started in the early Twenties, spreading out from the gymnastics society in Northern Italy. As soon as possible, the Italian basketball players switched from the traditional gymnastic outfit (including tights) to the more practical shorts.

The ‘Mens Sana’ Siena gymnastic (and basketball) team (1924)

Source: p. 24 of http://bit.ly/2GJUuOP

In April 1923 the Women’s Olympiad took place in Monte Carlo, Monaco. When the Pro Patria players competed against their Czechoslovakian opponents, the first wore shorts, the latter skirts: at that time, Italy was at the cutting edge, compared with the Eastern Europe country. Some years later, roles would to be reversed …

Italy – Czechoslovakia 15 – 13

Source: https://bit.ly/2VjTSZO

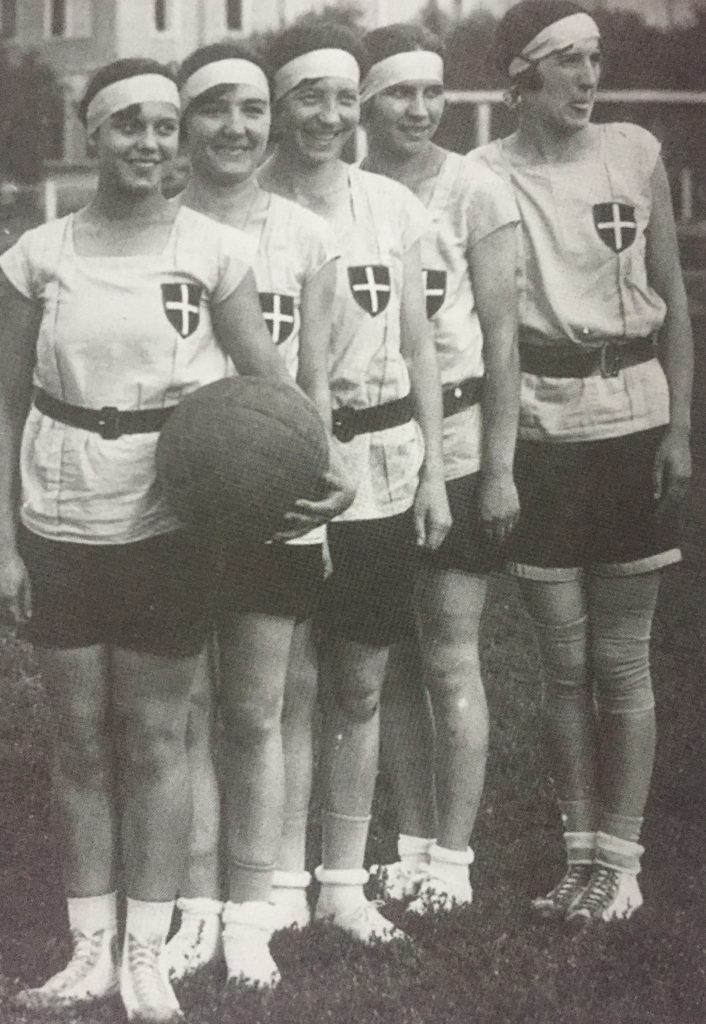

Moving on to 29 July 1928, when the Italy National Team played a match in Milan against the “Canada National Team”, which was the Commercial Graduates Basketball Club from Edmonton. There was a huge debacle: the hosts won 62 – 2! What’s interesting for us is that, despite the difference in the quality of their game, both Italy and Canadians wore shorts; the Italian added an headbands and the Canadians, knee pads.

Italian and Canadian players before the match

Source: https://bit.ly/2VjTSZO

The Italian National Team

Bruna Bertolini, Angelica Servi, Maria Piantanida, Giuseppina Ferrè, Lina Banzi

all wearing shorts

Source: https://bit.ly/2VjTSZO

Italian and Canadian players during the match

Source: https://bit.ly/2VjTSZO

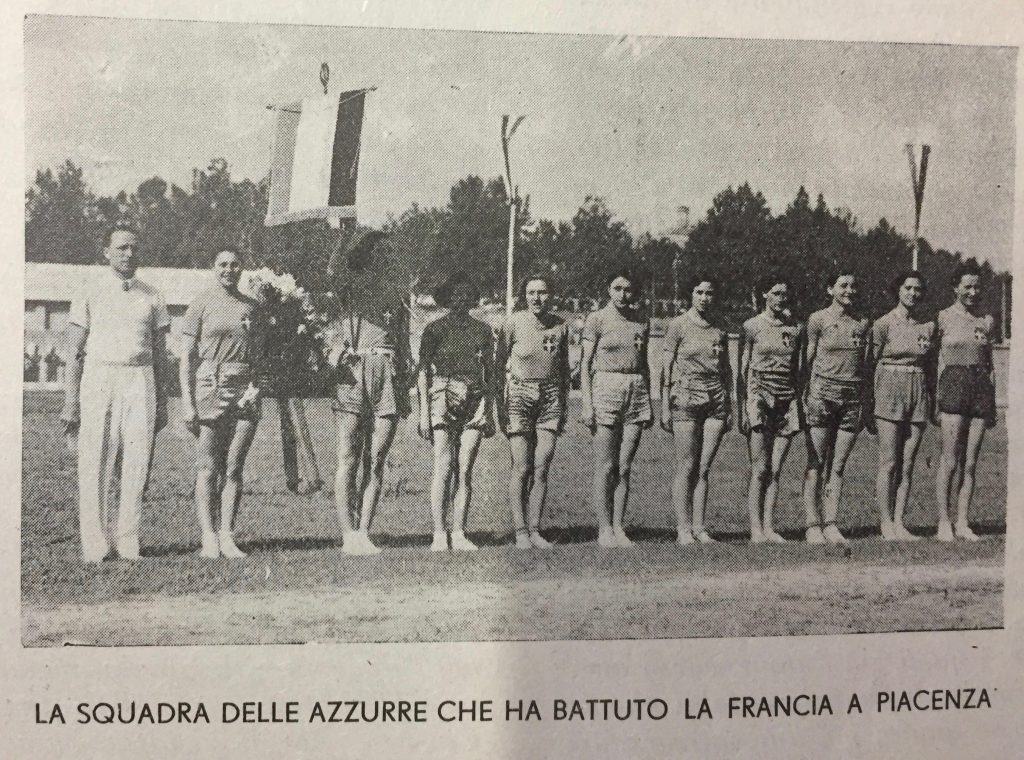

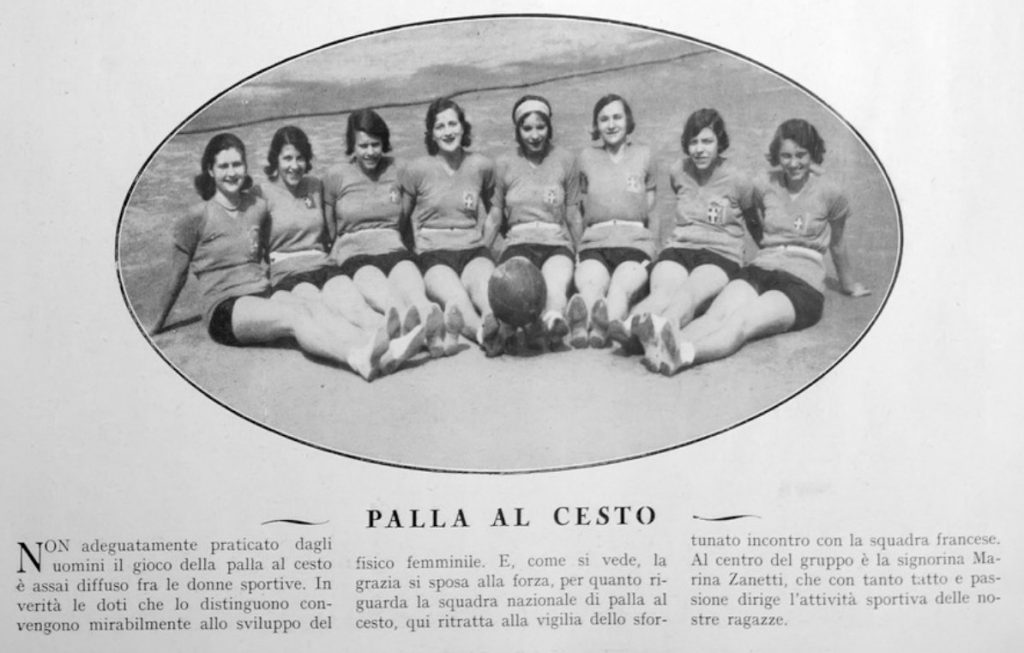

Still in April 1930, the players of the National Team posing for a photograph wearing shorts, prior to the match against France: it was the last time they would do so…

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, Maggio 1930, p. 29

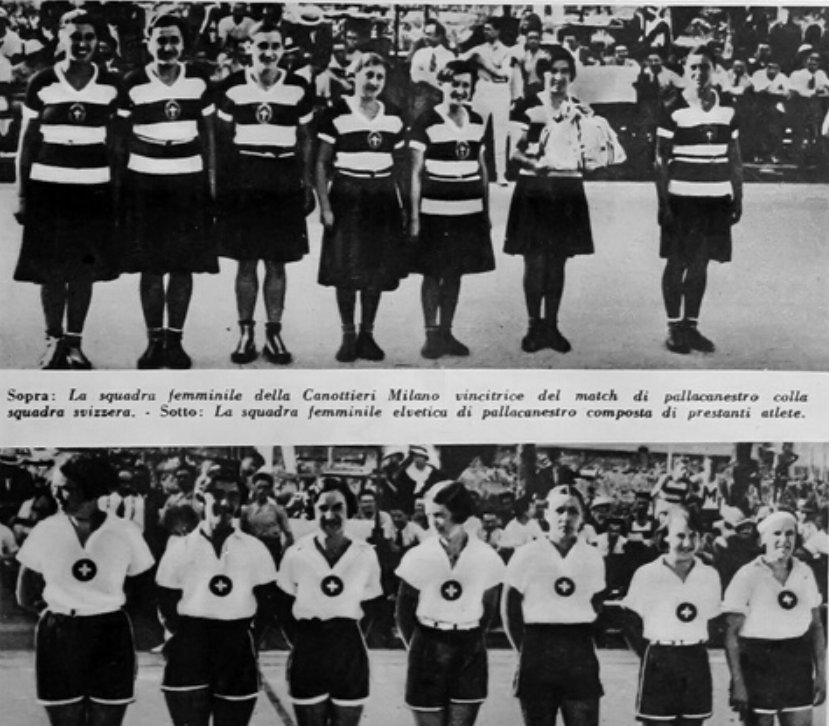

When the Canottieri Milano team, playing as a sort of Italy National Team (they were Italian Champions), defeated a Swiss “National Team” (July 1933), they were playing in skirts, as they are used to do during the National Championship from 1932 (maybe 1931, while in 1930 players was still wearing shorts: see https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1079363960212738049 ).

Italian and Swiss players before the match: Italians in skirts, the Swiss team in shorts

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1023290329661886466

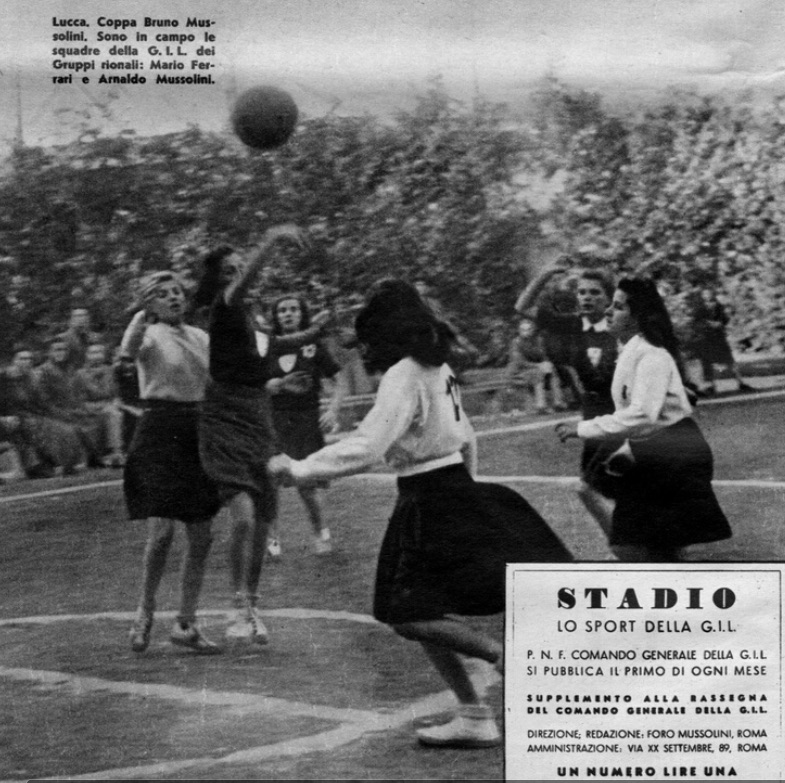

The passage from 1920s’ shorts to 1930’s skirts was a sort of sea change, because it coincided with the increase of Italian girls, assisted by aid from the regime. During this decade, basketball was encouraged by all the women’s Fascist associations (ONB, OND and GUF) and seen as the perfect female team sport. Women from all over the country (including small towns, and even the colonies in Africa! see – https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1138040625889251328) were introduced to it, and their skirts became one of the visual symbols of 1930s and 1940s Italian donna nuova.

Source: Stadio, July 1943, p. 9

Source: Stadio, June 1943, p. 2

Medal of a Giovani Fasciste championship (1937) on the left and on the right a medal of an unknown championship (no date) Source: https://bit.ly/34K1G9e

The most symbolic moment of the 1930’s/1940s’ Italian women’s basketball movement was the gold medal at the European Championship, won in Rome in 1938: the azzurre were the only players in skirts, all their opponents played in shorts.

The Italy National Team before a Euro38 match, wearing skirts

Source: https://bit.ly/3fjEEen

The Lithuania National team before a Euro38 match, wearing tracksuits

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EuroBasket_Women_1938_squads

Rome, 1938: EuroBasket Women 1938 match Lithuania v Italy 23 – 21

Note the difference in kits!

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EuroBasket_Women_1938

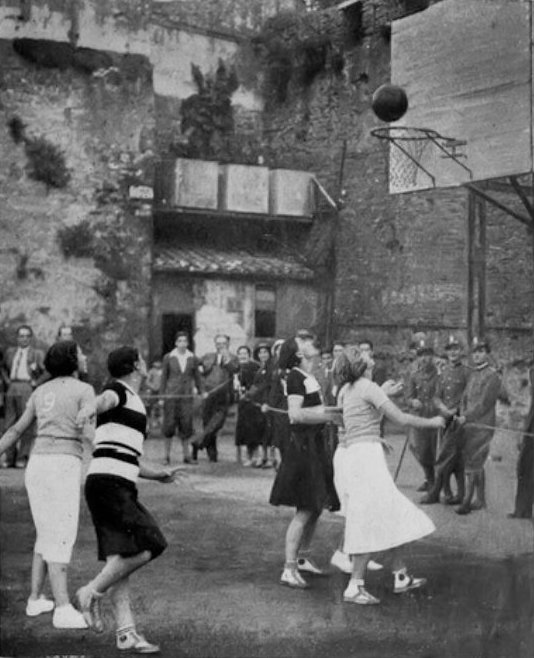

Photographs can help us understand that not all basketball skirts were the same: they were different in colour, shape … and length! In the picture of the 1933 Final Match: the Canottieri Milano players’ skirts are knee-length, while the AP Napoli skirt is much longer, almost level with the socks

The 1933 Final match between Milano Canottieri (dark skirts) and AP Napoli (white skirts)

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, August 1933, p. 51.

The Napoli players during a break (1932)

Source: La Voce Sportiva,19/05/1932, p. 4

We can see the same difference in the picture of the first-ever women’s basketball match in Lodi between the “apostles” from Milan and the local players, so we can maybe assume that the difference between medium length skirts and longer ones was not related to pure geographical difference (Northern cities vs. Central and Southern ones), but perhaps more to social evolution. Probably the Milanese players were more open-minded to wearing a medium length skirts (women from Turin and Trieste played in shorts, in the 1930 Final Match), as we can see from the late 1930’s and 1940’s Ambrosiana team picture where former footballer Rosetta Boccalini played (see https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/football/and-then-we-were-boycotted-new-discoveries-about-the-birth-of-womens-football-in-italy-1933-part-7/ ). The players confidence was maybe weaker and/or the team managers bigotry bigger in rural towns such as Lodi or in the more conservative city of Central and above all Southern Italy. Although we’re are referring to a general trend and not hard and fast rule (see for example the very long skirt worn in 1937 by players from Trieste and Venice, two of the most open-minded Italian cities at that time: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1331182296154726400 ), this explanation seems to be valid even after WW2. In a history of women’s basketball in Novellara, a small country town near Modena, we can read that after 1945 local players didn’t feel confident enough to play in shorts as the Modena players did: so they were still wearing skirts …

The first-ever women’s basketball match in Lodi

Source: Azzurri, 08/06/1934, p. 2

Napoli and Roma players, both in long skirts

Source: Il Littoriale, 28/03/1934, p. 3

Players from Faenza (1942)

Source: https://bit.ly/34K1G9e

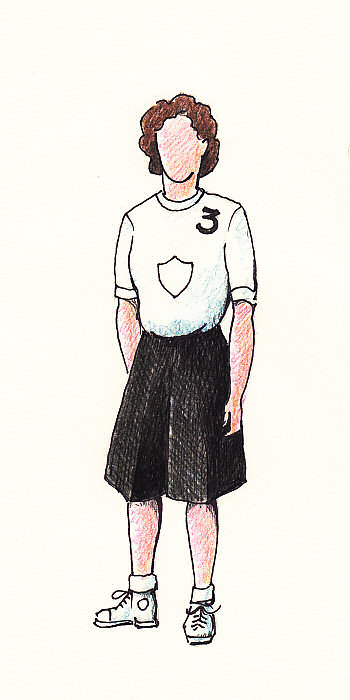

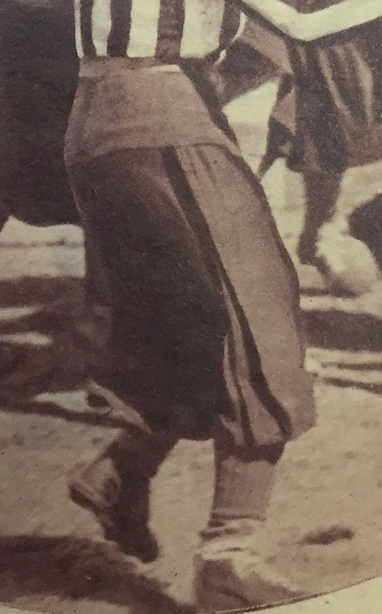

One may wonder how the women could have played in these skirts: the analysis of some of the pictures can help us in shedding light on this topic. In fact, basketball skirts were not simple sottane ‘skirt’, but sottane-pantalone, a kind of skirt with a internal slit: so similar to culottes.

This kind of skirt is still used nowadays by some Italian female scouts

Source: https://www.abbigliamentoscout.it/prodotto/gonna-pantalone-scout-gabardina/

Source: https://www.legabasketfemminile.it/Media/NewsDetail.aspx?NewsID=7880

Model of a GIL Capodistria basketball player (1942)

Source: https://bit.ly/2V7VRk4

Napoli vs. Roma Parioli (no date)

Source: https://bit.ly/34K1G9e

Euro38 Champion Anna Maria Giotto

She died one month ago, aged 105

She was the only player of the Italy National team who won Euro1938 that was still alive until recently

Source: https://primatreviglio.it/sport/bergamo-dice-addio-ad-annamaria-giotto-105-anni-fu-campionessa-europea-di-basket/

The sottana-pantalone was exactly the last kit of the GFC footballers (see bit.ly/2NBMzZg ). As we have previously seen, since they had established the first-ever Italian women’s football team (1933), the Milanese girls wore skirts exclusively, although the Italian press who was for the most part were against them, loved to depicte them as lascivious girls in shorts.

The first-ever GFC team picture, taken in studio, the girls had not started to play

Source: Il Calcio Illustrato, 15/03/1933, pp. 8-9.

Rosetta, Ninì, Brunilde, Losanna and their friends started to play wearing their ordinary everyday skirts, as we can see from the different shapes and colour, but soon they realized that they needed something more practical for the game.

Source: Il Calcio Illustrato, 29 marzo 1933, p. 11.

A home made skirt: seams could be seen – please remember that a lot of GFC players were seamstress …

Source: Il Calcio Illustrato, 29 marzo 1933, p. 11.

Some skirts were really original

Source: Il Calcio Illustrato, 22 marzo 1933, p. 16.

A further practical problem was that during the team picture the players seated in the front row were trying desperately to cover their legs, in order to avoid ‘improper poses’ …

Jole Mantoan is holding the skirt against her knees, Ninì Zanetti has rolled it over her legs, Luisa Bocclaini is using a ball, and Losanna Strigaro has straightened her the skirt from the side … what a pain!

Source: Il Calcio Illustrato, 15 marzo 1933, pp. 8-9.

In April 1933 the players found a solution, ordering (probably thanks to Margherita Loverro’s father, who was the owner of a sportswear shop) a stock of dark sottane-pantalone [culottes or divided skirts]

The GS Cinzano team (Summer 1933)

Source: Archivio private Rosa Mottino,

Even in the case of the 1933 footballers we don’t really know is they were forced to play in skirts, or if they decided to do so. What is sure is that their sottane-pantalone were more practical than the white short skirts adopted by some Dutch amateur footballers of FC de Rakt team, who some years ago (2008) had asked the local Federation for the right to play in skirts (see https://t.co/L262qywP9m?amp=1 ) … in fact, they had to wear additional shorts underneath!

The FC de Rakt players [2008] – it was an amateur team who asked the local Federation for the right to play in skirts

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1258456639302258701

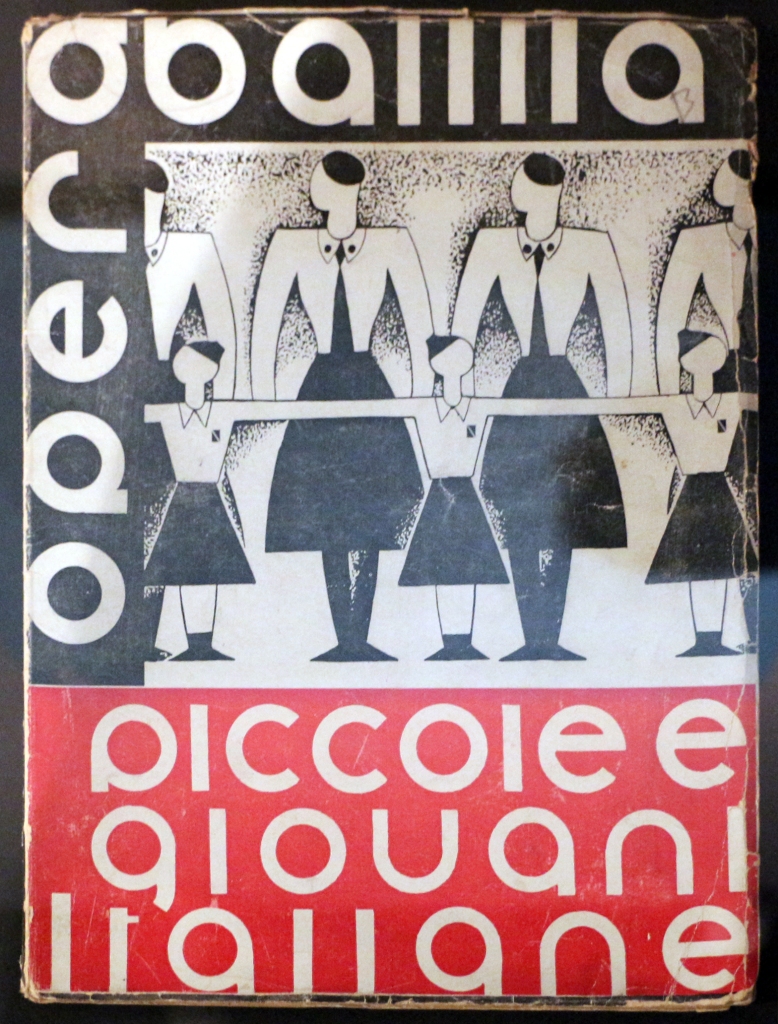

In Ricci’s ideology, there should be no confusion about the gender roles of future mothers and soldiers, as we can see not only looking at the different activities (Giovani Italiane attended childcare and home economics courses, while their peer Avanguardisti were taught to use rifles), but also at the different uniforms. The basic distinction between the Balilla (boys from 6 to 14 years) and Piccole Italiane was that the first wore shorts, the second a dark skirt.

Piccole Italiane (on the left) and Balilla (on the right) performing the Roman salute, in front of a column – probably a memorial of WW1 fallen

Source: https://fotoedu.indire.it

A postcard depicting Mussolini greeting a Balilla and a Piccola Italiana

Source: Collezione private Enzo Pelma, https://www.cartolinedalventennio.it/free-extensions/collezione-privata-enzo-palma?switch_to_desktop_ui=830&page=4#category

Shorts for boys, skirts for girls … Giovinezza ‘Youth’ was the most famous Fascist song

Source: Il Giornale della Donna, 1 settembre 1933, p. 5.

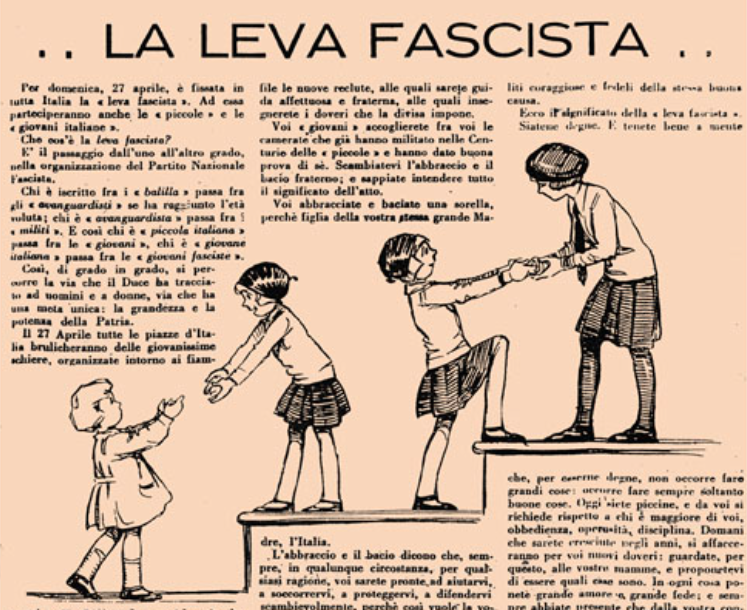

On May 24th not only was there a huge ONB meeting in every Italian city, but also a specific ceremony, called Leva Fascista, by which every 14-years-old Piccola Italiana became Giovane Italiana: her skirts became a little longer, and her tights darker, as every respectable young lady was expected to do.

The double Leva Fascista: from little girl to Piccola Italiana, and then from Piccola Italiana to Giovane Italiana

Source: Fonte: La Piccola Italiana, 27 aprile 1930, p. 3

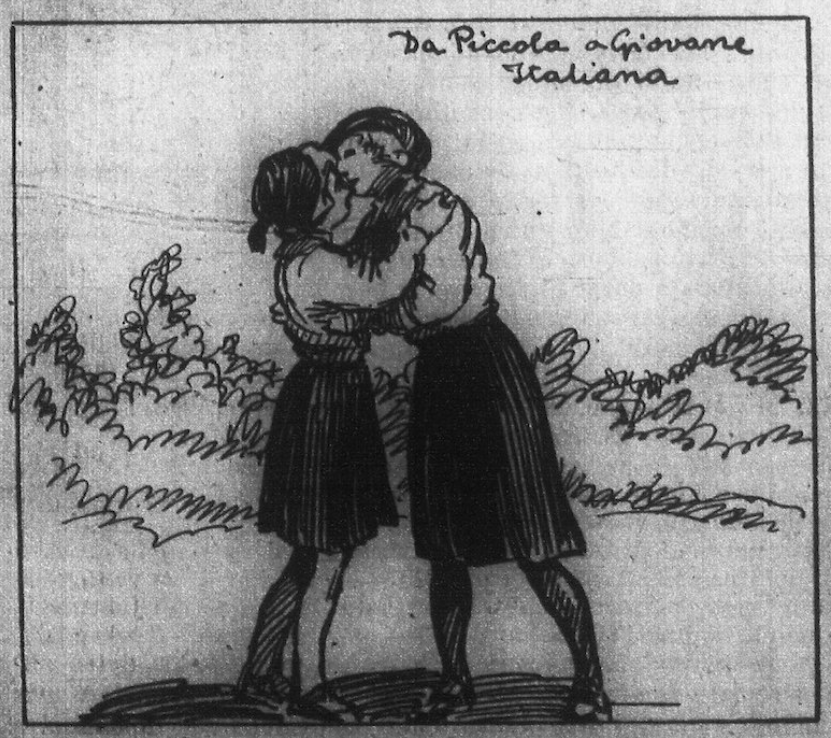

The passage of rite ceremony: the Piccola Italiana being kissed and embraced by a Giovane Italiana

Source: Fonte: La Piccola Italiana, 20 maggio 1934, p. 7.

The 1938 Leva Fascista in Rome, Bologna and Milan. Source: https://youtu.be/K0_ZHy3rzLM

On this notebook cover you can see the chromatic difference between dark-tighted Giovani Italiane and white-tighted Piccole Italiane

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piccola_italiana

Piccole and Giovani Italiane uniform were a different kind of uniform from the one worn in school: the difference being that the ONB uniform could have military-type stripes. It was the first time that Italian women were allowed to wear stripes: please remember that just some years later, in 1943, Italian women would fight during the war, for the Resistance (partigiane) or for the Fascist Repubblica Sociale Italiana (ausiliarie). Probably one of the reasons for such a seemingly incomprehensible fact: a lot of women interviewed after 1945 about their youth during the regime remembered how they wished to get that uniform, which was a real uniform … something that their older sisters and mothers weren’t allowed to dream of.

Three Giovani Italiane in the Milanese countryside (1940)

Notice the stripes on the shirt of the third girl

Source: http://www.cassinettadilugagnano.com/cdl_raccolta.asp?id=FotoAnni40

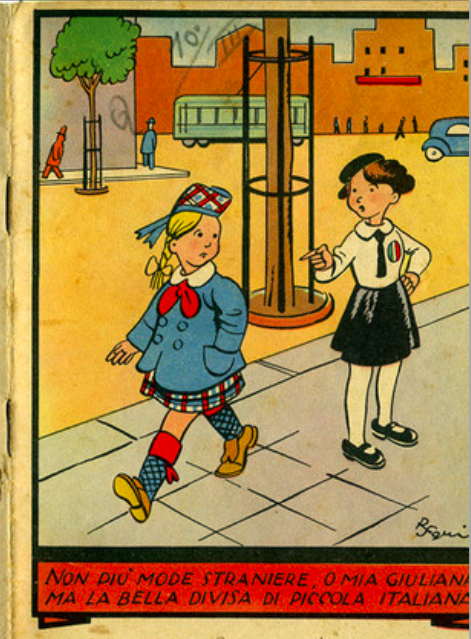

A notebook cover says:

‘No more foreign fashion, my Giuliana. But a nice Piccola Italiana uniform!’

Source: http://www.arte.it/notizie/bologna/a-lezione-di-razzismo-al-museo-ebraico-di-bologna-10022

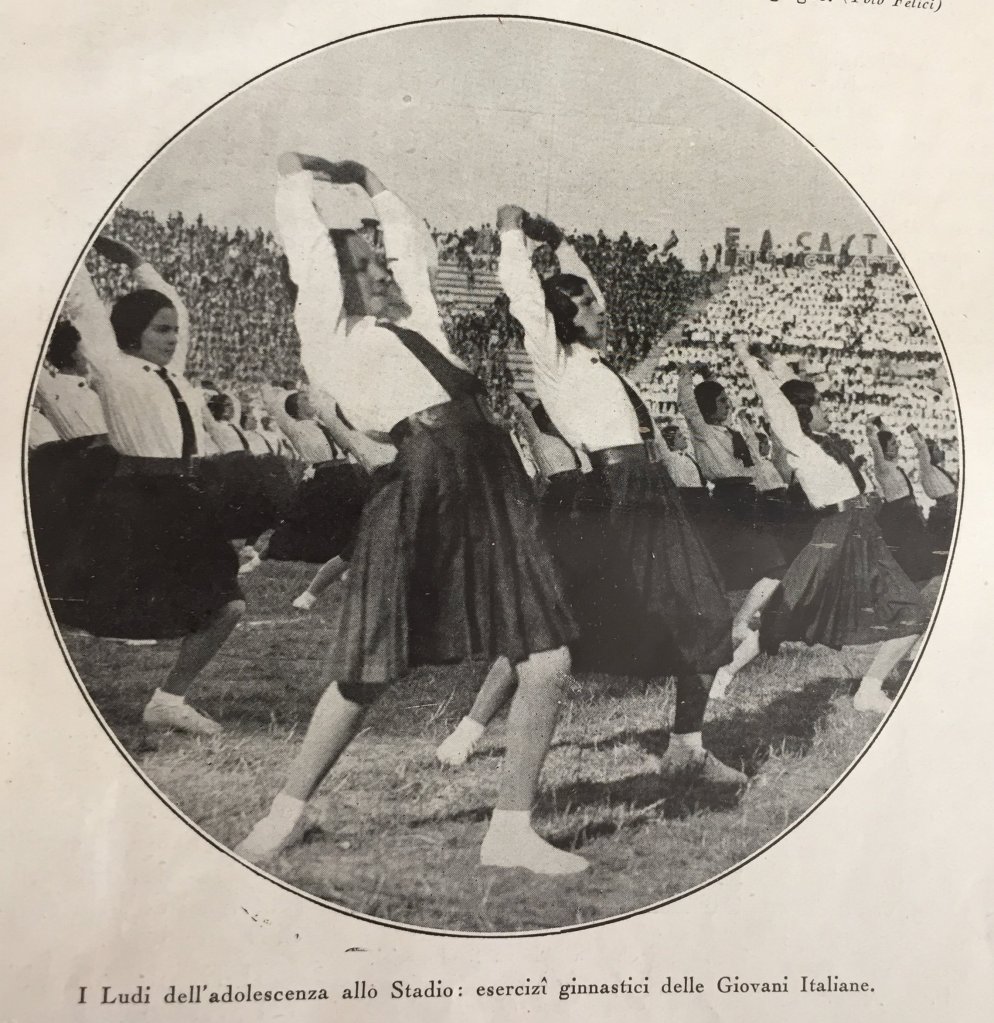

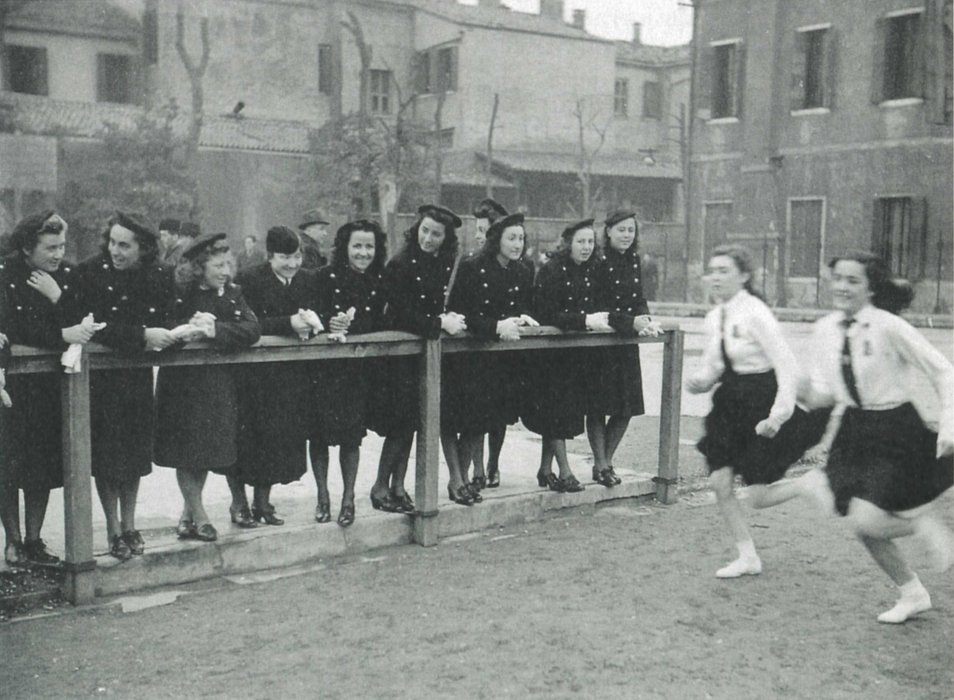

Sports was one of the main activity encouraged by ONB: simple games for Piccole Italiane, more complex games (basketball, sometimes volleyball) and sports (gymnastics, athletics, swimming, skiing, ice-skating …) for Giovani Italiane.

Piccole Italiane during a gym lesson (1930s’)

Source: https://fotoedu.indire.it

Giovani Italiane during a gym lesson

Source: https://fotoedu.indire.it

For some of these activities (i.e. the annual collective gymnastic choreography), the uniform remained the same, but they were allowed to change their long tights to short white socks, and dark shoes to some more comfortable tennis shoes. In the most conservative part of the Kingdom of Italy, such as inner Sicily, these short socks were perceived as a scandal: as told by Sergio Giuntini in his La rivoluzione del corpo (p. 55), in 1935 the Bishop of Noto complained because the high school female students in Modica were asked to play during a public gymnastic event in front of the audience with their tights pulled down, showing their naked legs.

Giovani Italiane during a public event (called ‘Ludi dell’adolescenza’ or Teen Games) in Rome (1932)

Source: L’Illustrazione Italiana, 19 giugno 1932, p. 829

Giovani Italiane with hoops (1930s’)

Source: Archivio Cesare Gabriele, https://www.cartolinedalventennio.it/free-extensions/collezione-cesare-gabriele?switch_to_desktop_ui=830

Two Giovani Italiane running in front of some Academics of Orvieto in Venice

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1067114365600653312

Talking about tights, remember the outfit of the very young Giovani Pavesi, the local team from Pavia which competed at the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam as the Italian National Team and won the Olympic silver medal – the only one in 93 years for Italian women’s gymnastics, before the 30-years old Vanessa Ferrari broke this curse some days ago! Although they trained bare-legged, for their Olympic performance their wore white tights, unlike their Dutch opponents who finally won the gold medal.

The Italian gymnasts before their performance

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, August 1928, pp. 53-60

The Italian gymnast training

Source: http://www.playingpasts.co.uk/this-week-in-sport-leisure-history/on-this-week-in-sport-history-womens-history-month-european-special/

The Italian gymnast squad performing

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, August 1928, pp. 53-60.

The Dutch women’s team, who won the gold medal for gymnastics at the Amsterdam Olympics, at the Olympic stadium with their assistant coach. Amsterdam, 8 August, 1928

Source: https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/sport/dutch-gymnastics-team.asp

Italian gymnasts being awarded with silver medals at the Amsterdam Olympics

Source: https://sport660.wordpress.com/2018/03/29/la-leggenda-delle-piccole-ginnaste-pavesi-ai-giochi-di-amsterdam-1928/

The fact was that, during that summer of 1928, a heated debate regarding sportswomen’s outfits broke out, unleashing several negative responses from the conservative-revolutionary Fascist regime.

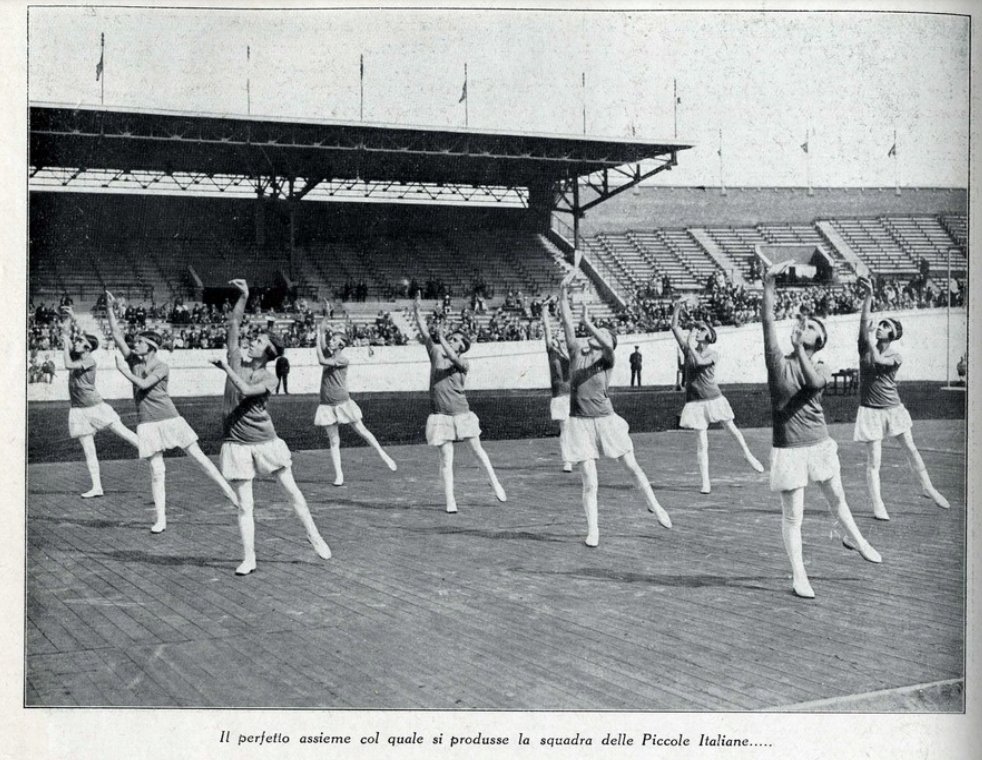

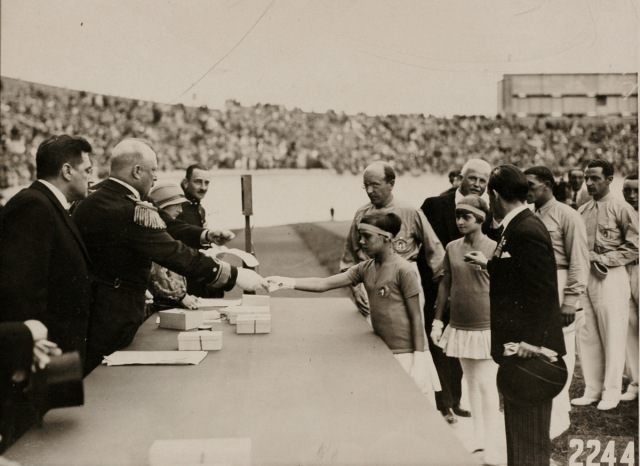

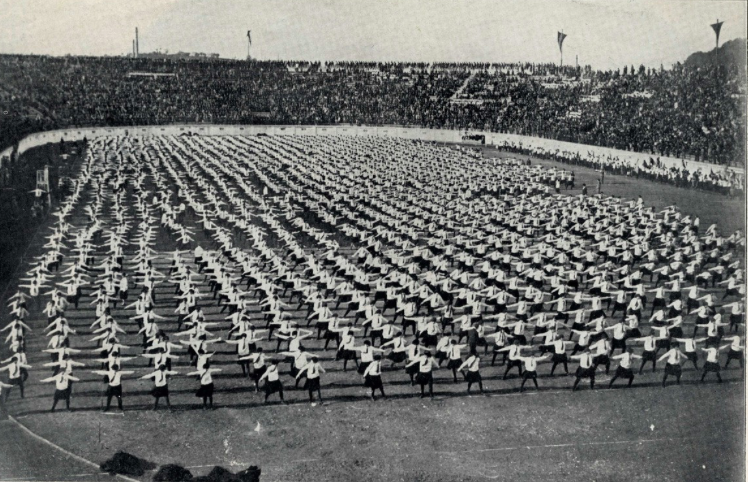

From 4 to 6 May 1928 the ONB organized the first-ever Concorso ginnico-atletico ‘Gymnastics and Athletics Competition’ for the Giovani Italiane, who were called upon to gather in Rome from all over Italy: Mussolini himself would attend the event and to award the winners their medals!

Collective gym exercise during the Rome Concorso (1928)

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, Giugno 1928, pp. 49-52.

Mussolini awarding a winner of the Concorso (1928)

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, Giugno 1928, pp. 49-52.

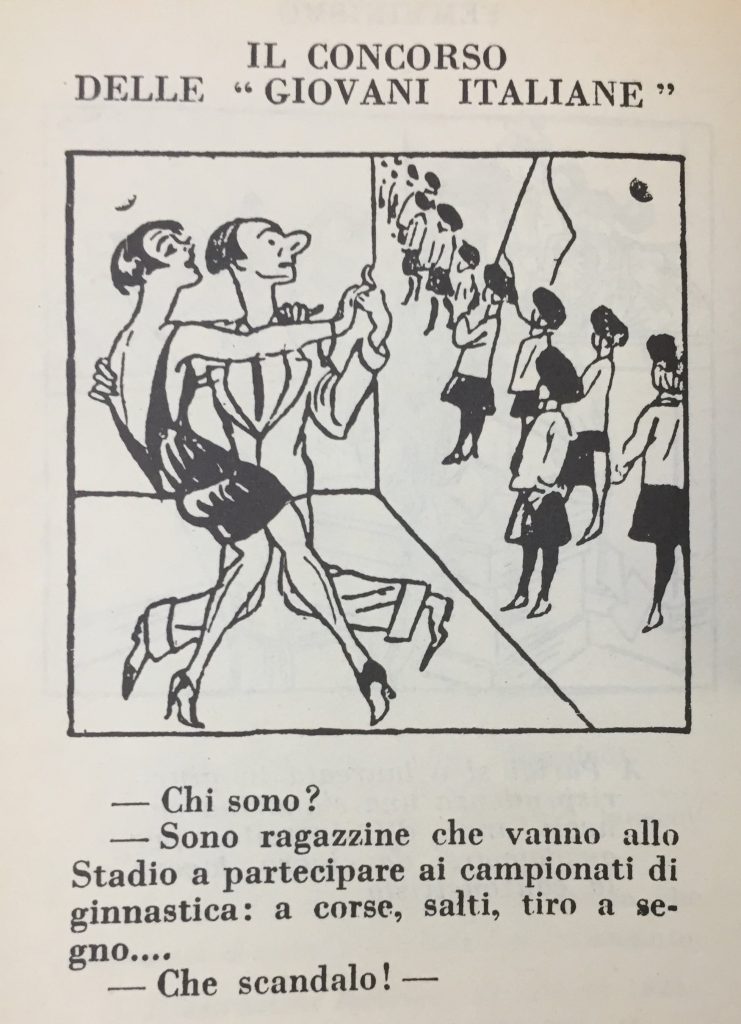

Pope Pius XI, who was a keen hiker himself but who also disapproved of women’s sport, wrote to the Vicar of Rome Cardinal Pompilj, not only complaining about the fact that in the Holy Capital City of Catholicism such a male and warrior-like activity such as shooting was included in the individual program (which included a hurdles race and javelin throw), but also underlining the immorality of throwing those innocent and pure young females to an adult male audience, in similar fashion as to what happened in ancient Greece and Rome. Some months later, Fascist Italy and the Catholic Church finally signed the Lateran Treaty, which settled the long-standing Roman Question. But the struggle between the Catholic Church and the Fascist regime about the body and the outfits of young Italian sportswomen had only just begun.

A satirical cartoon about the 1928 Concorso, which blames the hypocrisy of some conformists, horrified at watching the Giovani Italiane gathering at the stadium … during a wild dance!

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1105555081318092801

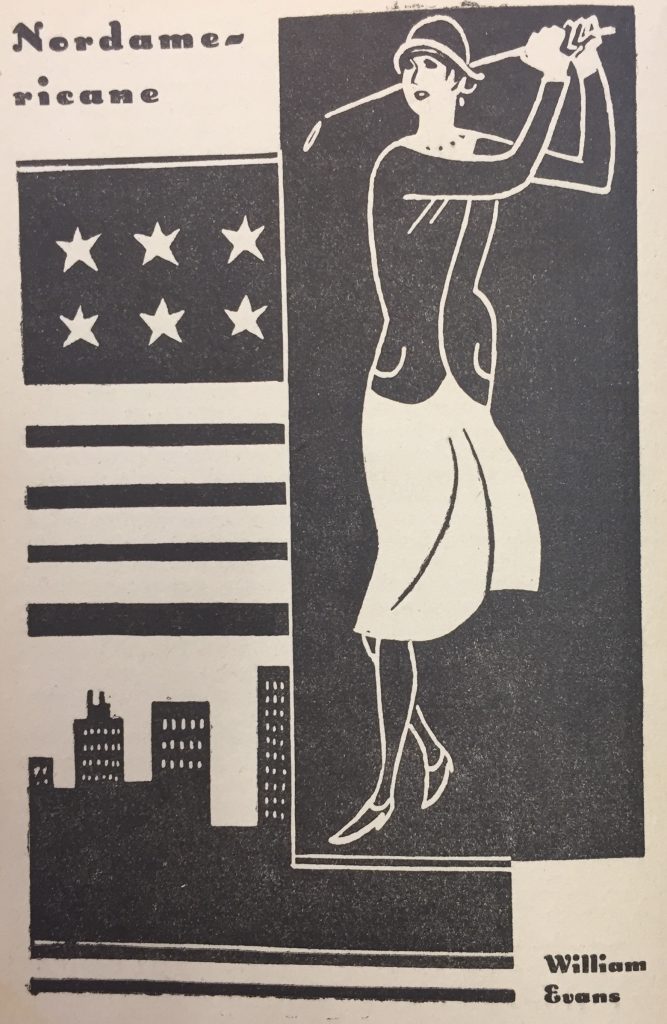

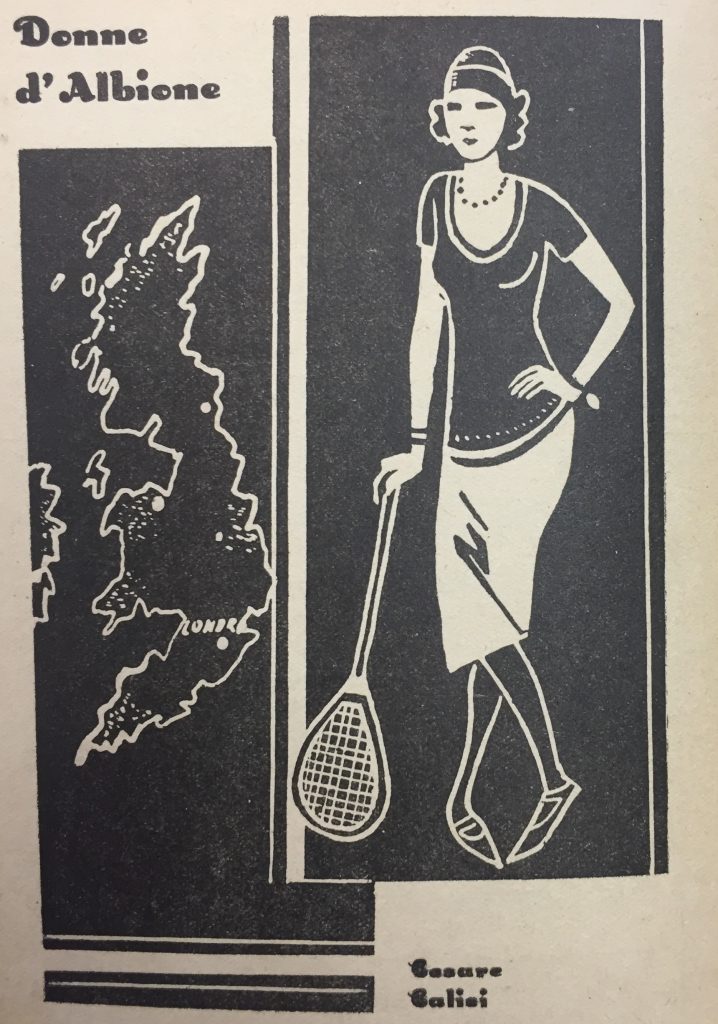

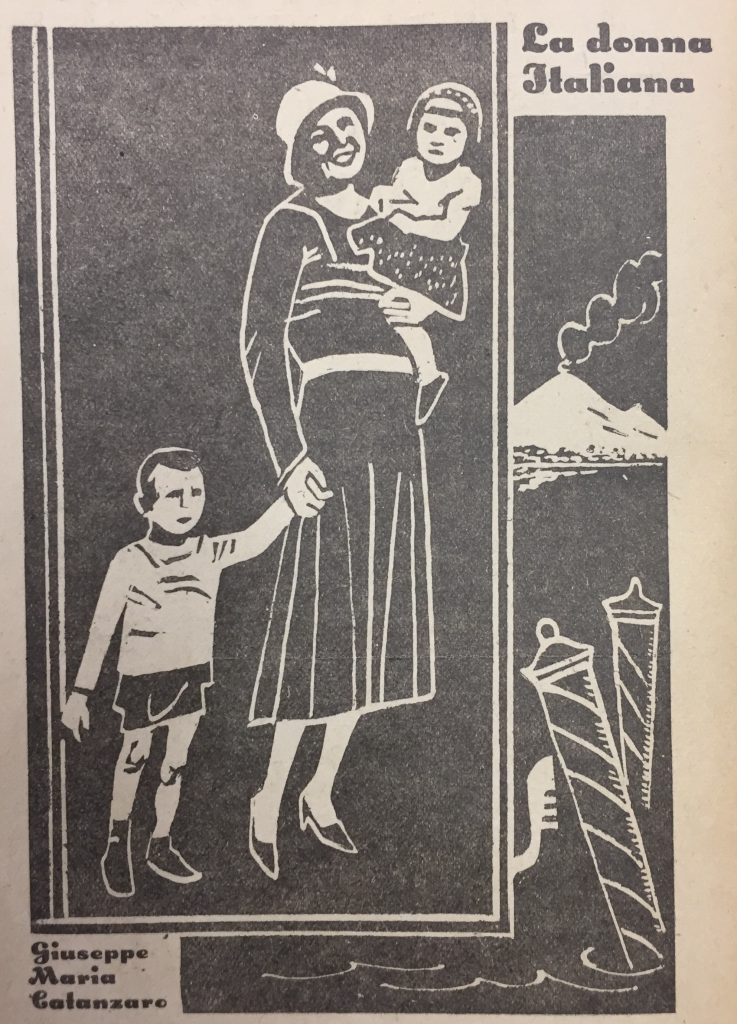

The Fascist regime had a quite paradoxical policy about Italian society. On one hand, it was very traditional, as with any right-wing dictatorship: despite all the images of individual, intellectual, and sexual freedom coming from abroad (especially the USA and UK), Italian girls must keep to the old ideals, which can be summarized in the “wife and mother” slogan. On the other hand, the regime didn’t want to seem outdated: what Mussolini did in 1922 with his Marcia su Roma was not told by the propaganda as a simple restoration, but as a real revolution. The ancient Roman civilization was an ideal model, not a goal: the rich Italian historical tradition was meant to be used to build a new, updated country that could compete with and even conquer the ‘corrupted’ Western liberal and capitalistic countries. It was the dream of a ‘third path’, which led not only to a uomo nuovo ‘new man’ but also to a donna nuova: a ‘new woman’ that, in spite of her primary maternal duties, was also was expected to be more active than her mother and grandmother, who spent their lives virtually tied to the home. The illustrator of Cordelia, one of the most important ladies’ magazine of that time, can help us with some visual images of these ideals. In the annual Almanacco of 1933, he depicted the American woman as a golfer and the British as a tennis player, both slim; the Italian mother, a little more chubby, and with her two children, but wearing a fashionable suit, not a traditional or regional one.

- Source: Cordelia’s Almanacco, 1933, pp. 74, 46 and 32.

Talking about fashion and censorship, this ‘third path’ was really problematic. The Italian newspapers and magazines had to give their readers information and images showing what women wore and how they lived abroad: a total censorship would seem absurd; as a counterbalance, the Italian press loved to rail against that donna-crisi ‘crisis-woman’ too thin, too free, too independent. But female readers were free to see such images, realizing that outside Italy there was another way to be a woman …

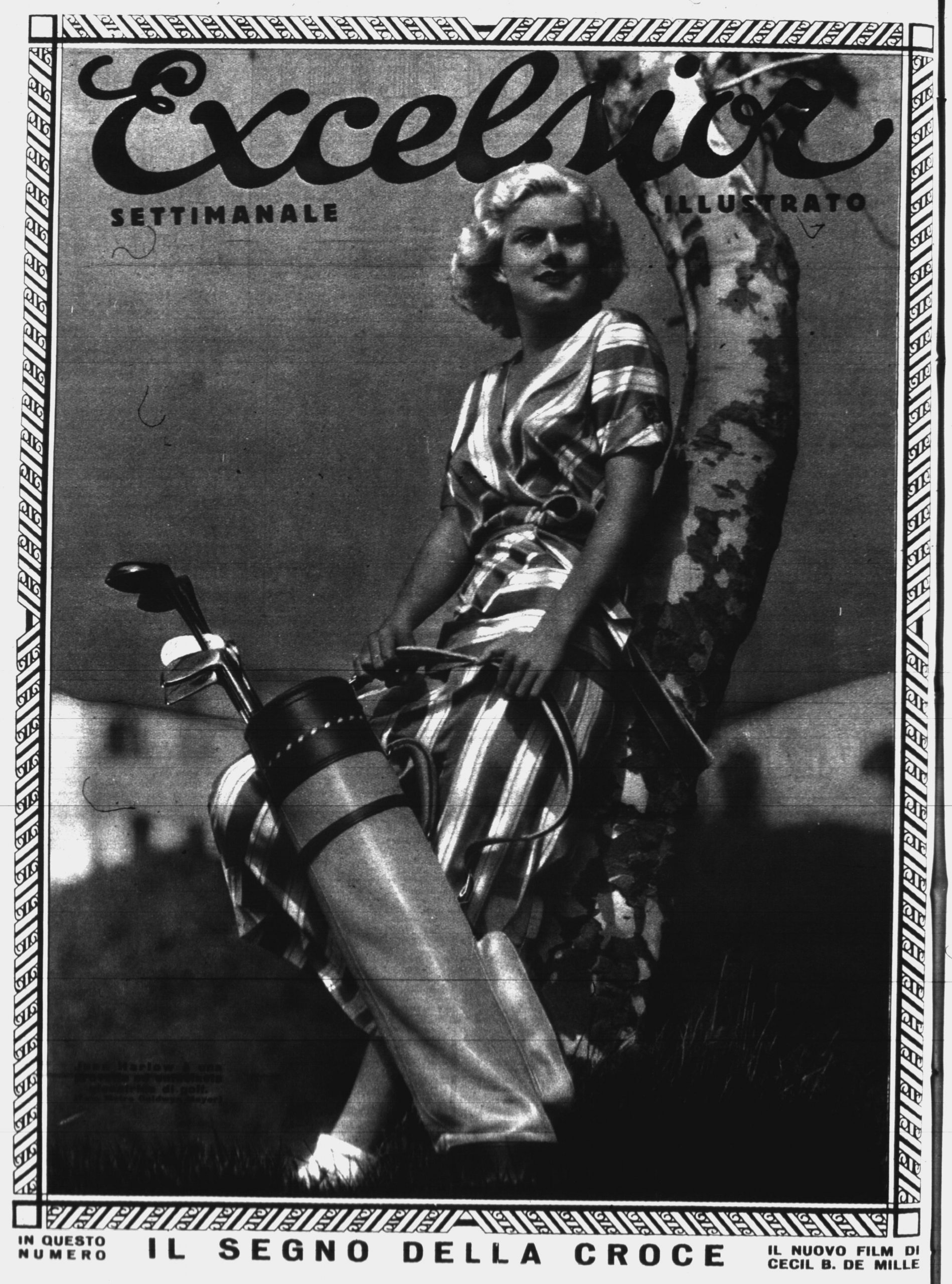

In the late Twenties and Thirties, in particular, there was a new female ideal that occupied the pages of Italian ladies’ magazines: the Hollywood actress. Italian readers were literally bombarded by articles and above all images (coming from US press agencies) regarding these beautiful, rich, and somewhat vain women, who lived in that overseas paradise. The fact was that sports was one of the primary elements of the Hollywood diva model: they loved it, they practised it, during interviews they explained how it helped them to shape their bodies, and even to find an husband!

Mabel Madern, the tennis player

Source: Piccola, 08/08/1933, p. 11.

Jean Harlow playing golf

Source: Excelsior, 15/02/1933, p. 16.

Sally Eilers playing tennis

Source: Piccola, 17/01/1933, p. 5

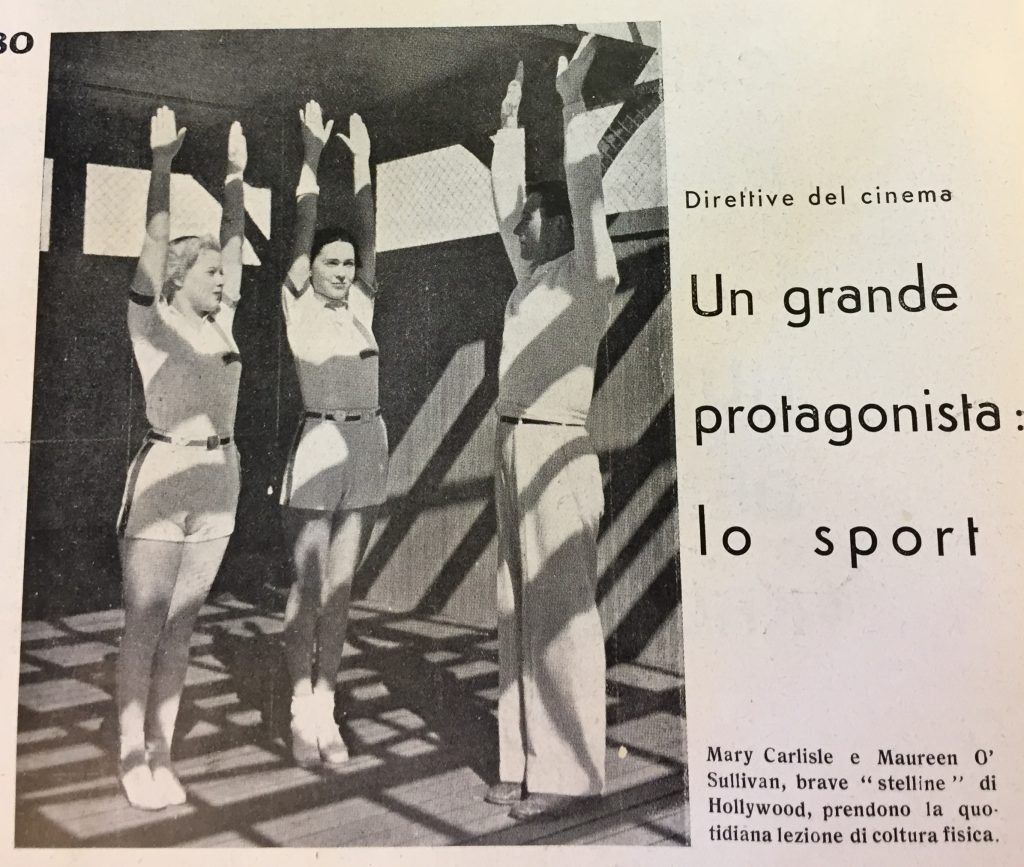

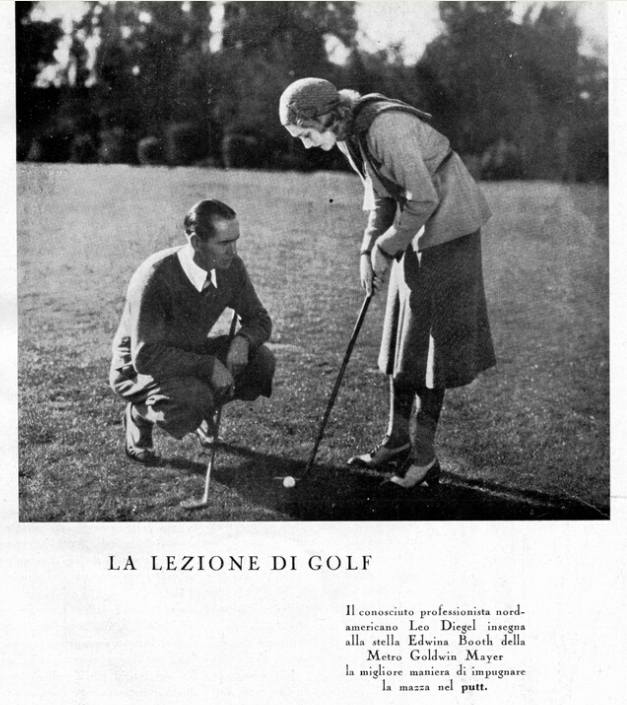

We all know that the vast majority of these photos are not “real”, but posed: however, they do convey some subtle visual messages:

1) A modern woman needed to be helped by trainers and instructors to take care of hew own body;

Mary Carlisle and Maureen O’ Sullivan taking gym lessons

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, Maggio 1934, p. 80

Edwina Booth taking golf lessons

Source: Golf, Maggio 1934, p. 33

2) Practicing together sports should be normal for men and women.

Lupe Velez on a bycicle, helped by Johnny Weismuller

Source: Piccola, 03/01/1933, p. 13

Johnny Weissmuller teaching his pupil Leila Hyams how to swim

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, July 1933, p. 76

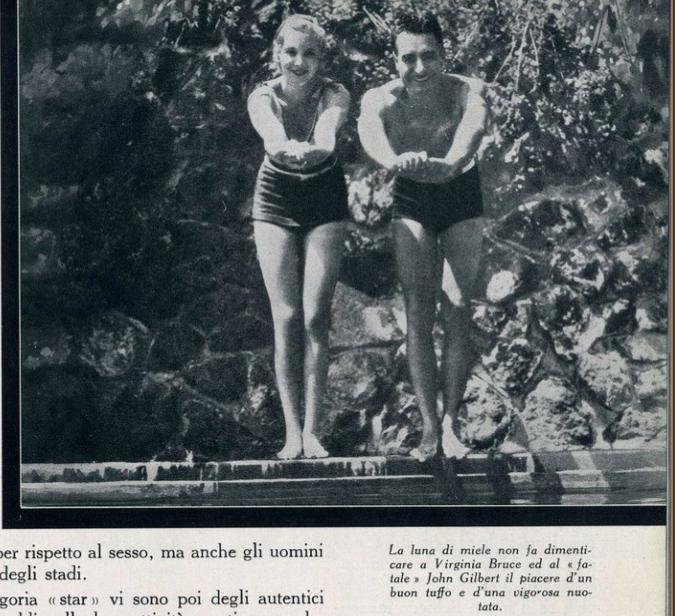

‘John Gilbert and his girlfriend Virginia Bruce playing tennis’ – probably the original press agency photo caption was out of date as they married in 1932

Source: Il Littoriale, 28/02/1933, p. 3

3) Women should have no fear in showing their body in a swimsuit

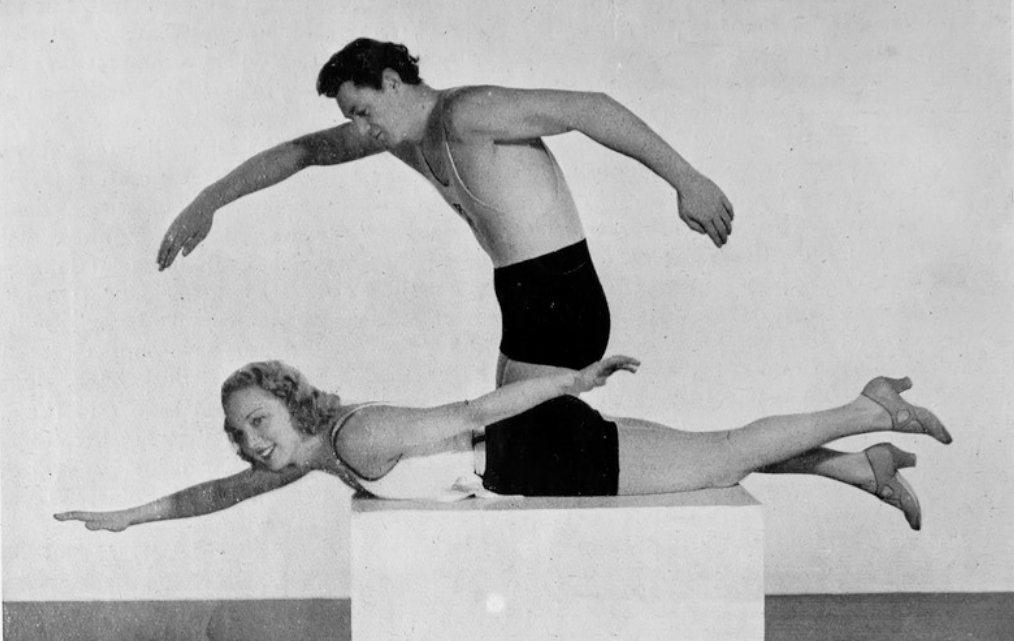

John Gilbert and Virginia diving in swimsuit

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, January 1933, p. 61

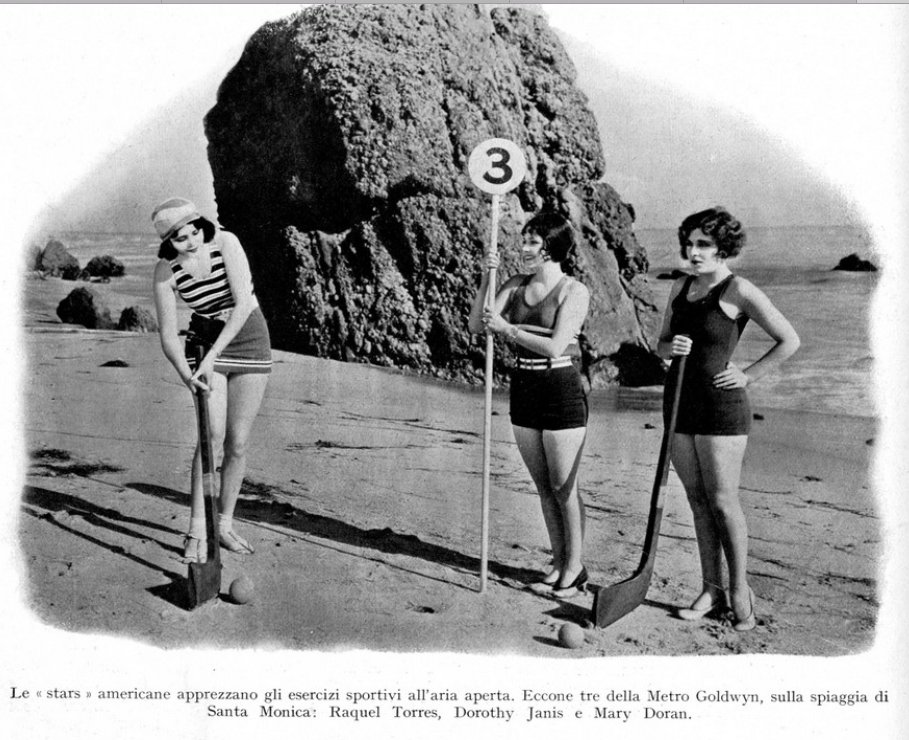

Raquel Torres, Dorothy Janis & Mary Doran (all wearing swimsuits) playing a sort of golf on a beach

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, April 1929, p. 36

The fact that the women portraited were not from Italy allowed magazines and newspapers to feel more confident in publishing almost every kind of picture. The trick was: first to publish those photos, then to write that those were foreign women, not ‘good’ Italians would ever do that or look like that. Yet it was a quite an ambiguous operation, and – what is more important – the eyes of Italian readers were now becoming accustomed to the new image of the sporting woman.

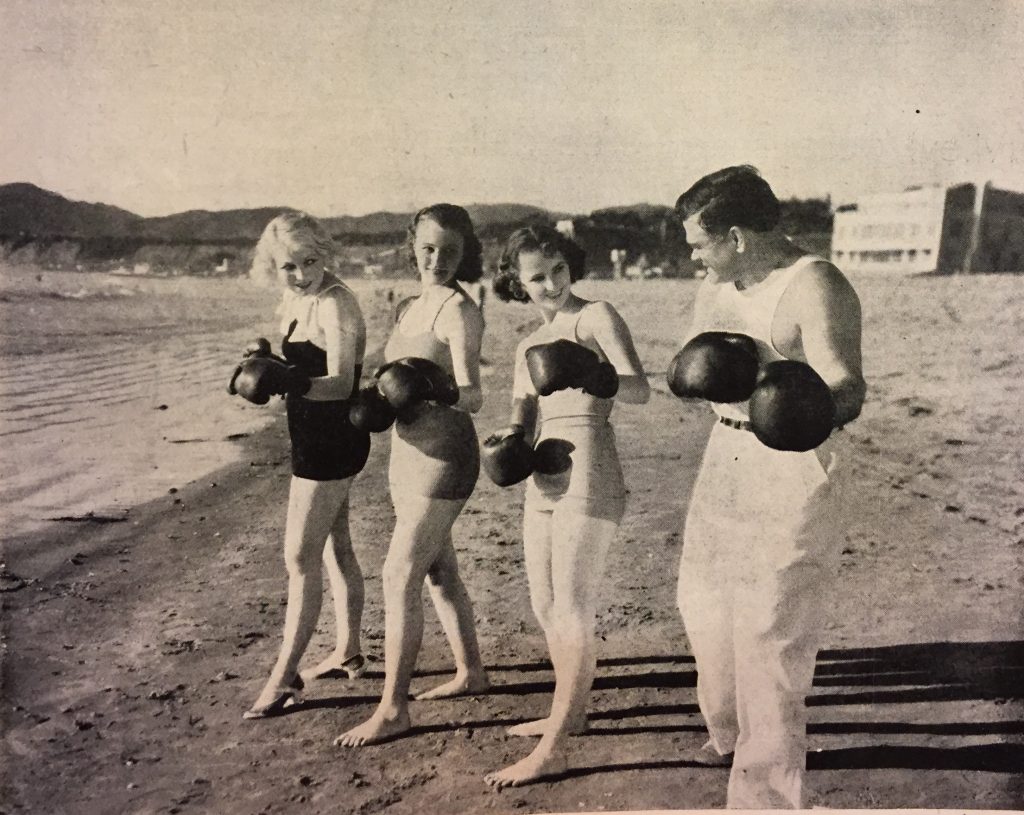

The caption says: ‘Trainer Max Baer teaches Muriel Evans, Linda Parker and Florinne Mc Kinney to box”

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, Febbraio 1935, p. 71

In the huge family of the Italian press, there were some allies of the modernization of women’s sportswear: the fashion magazines, which are a rich but still under-used source for the study of Italian Sports History.

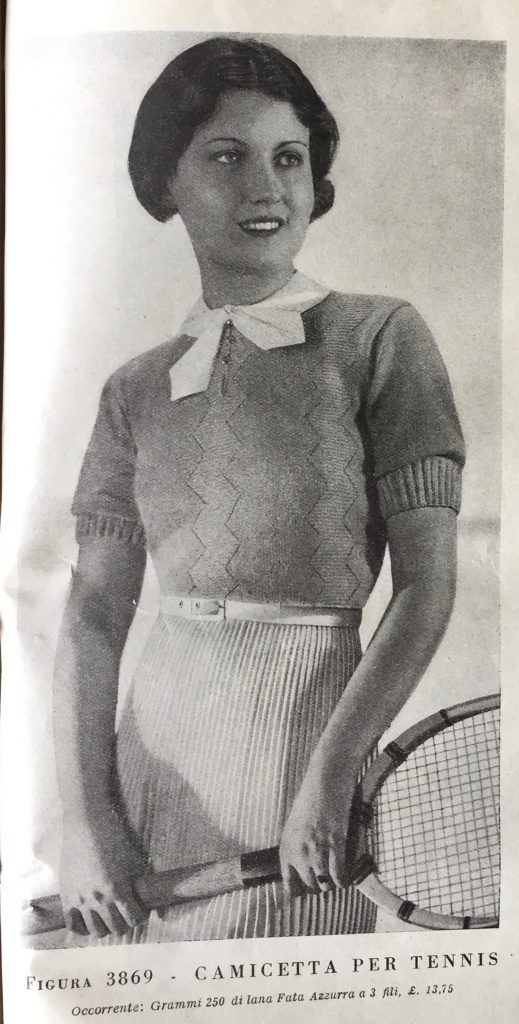

A tennis model

Source: Mani di Fata, 01/04/1933, p. 27

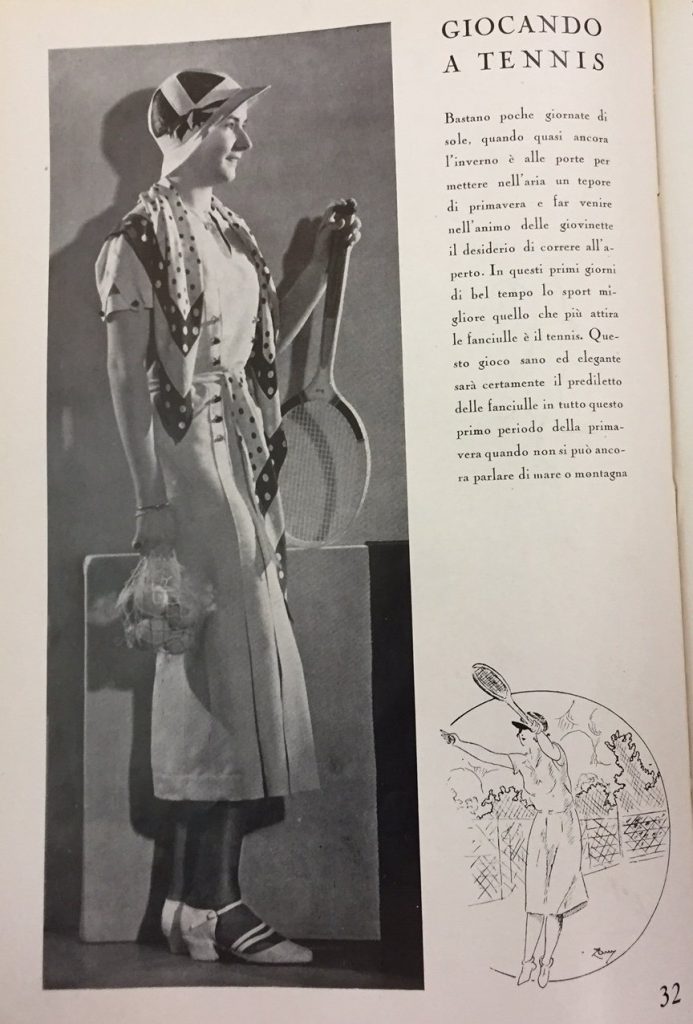

Another tennis model

Source: Fior D’Eleganza, 01/04/1933, p. 32

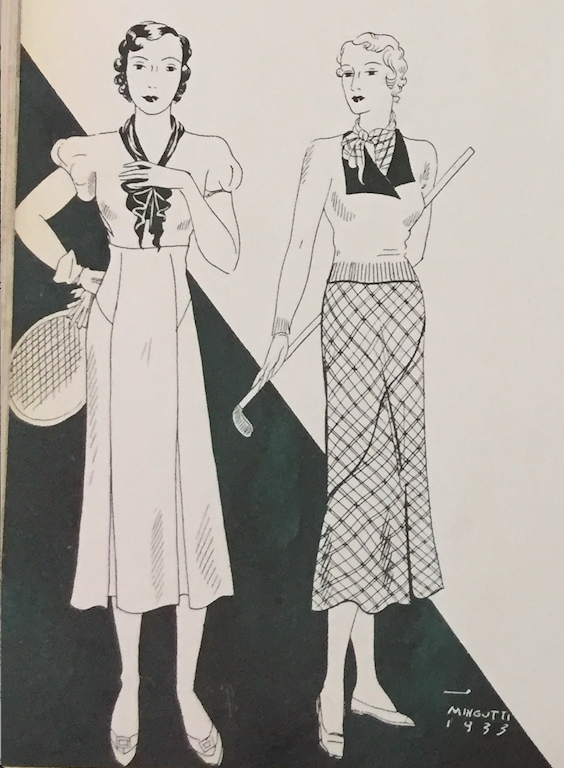

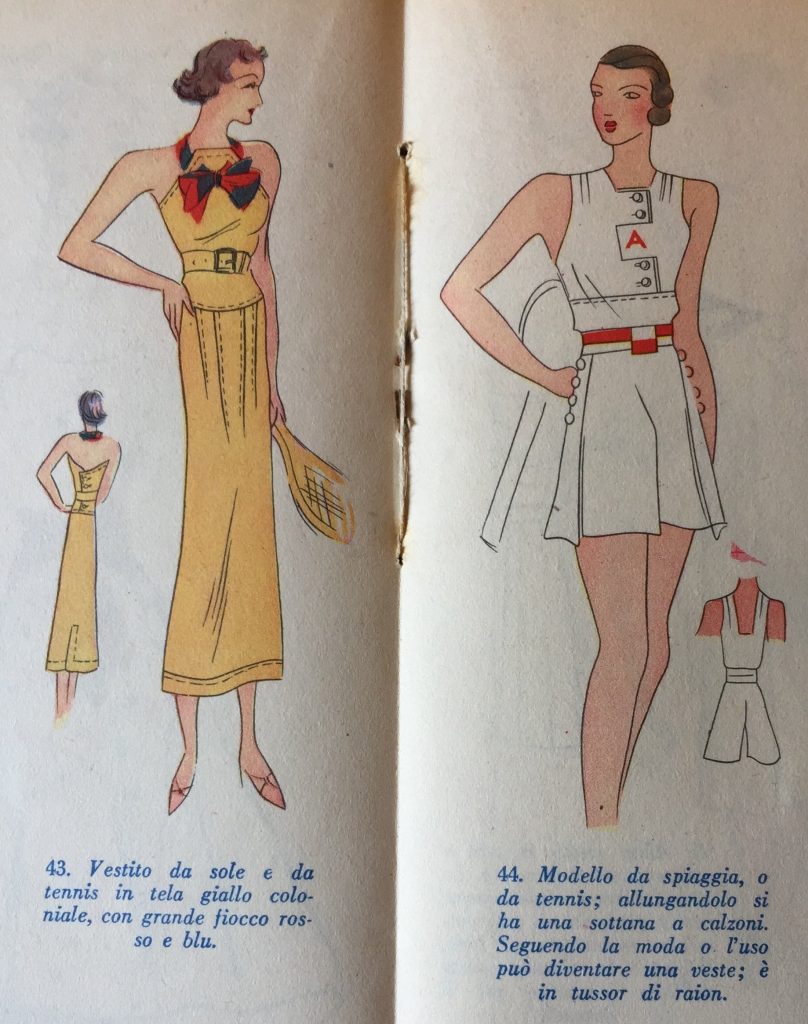

A tennis model, and a golf model

Source: Fior D’Eleganza, 01/05/1933, pp. 28-29

Being generally read only by the woman and usually not political, these magazines were mostly ignored by the Fascist censorship: but they had their ideological policies, and they conveyed some views concerning women’s sportswear. The main being that wearability should be the only one criterion to use when talking about any kind of spotwear, be it skirt, shorts, ski pants …

A female climber model: the caption says that the skirt with double split is very large, in order to get a better fit

Source: La Gazzetta Dello Sport, 23/07/1933, p.

Let’s take for example a image of a model in a tennis dress published by La Gazzetta dello Sport in June 1933. The sottana-pantalone is praised because, it avoids the possibility of showing underwear ( the main problem of traditional long skirts), giving the players a better rage of movement. Functionality was also the main value of the headband.

The tennis suit model illustrated by La Gazzetta dello Sport

Source: La Gazzetta dello Sport, 04/06/1933, p. 3

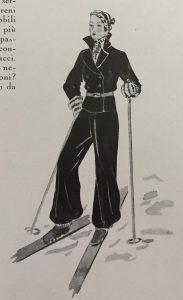

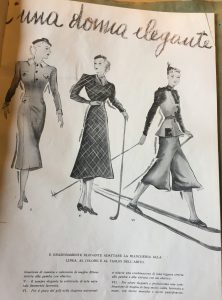

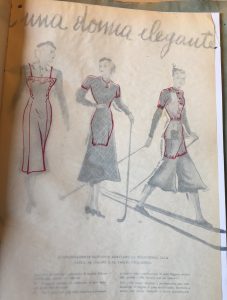

Functionality should go along with beauty and elegance, of course: the fact was not to campaign for pants or shorts, since an elegant women should be able to find a graceful and stylist way to dress in both shorts or more a traditional skirt. In her article La giornata della sportive, Rita suggests to her female readers not to use the same clothes during a day spent on the mountains, but to use one suit for the travel by train or by car (a tailleur), then one for the skiing (including ‘Norwegian-like wool trousers’), and at last one evening suit for dancing at the hotel.

-

3 models from Simonetta’s article

Source: Fior D’Eleganza, 01/03/1933, p. 15

Golf skirts and trousers

Source: Vita Femminile, Aprile/Maggio 1935.

Tennis skirts and shorts

Source: Vita Femminile, Giugno 1936, pp. 22-23

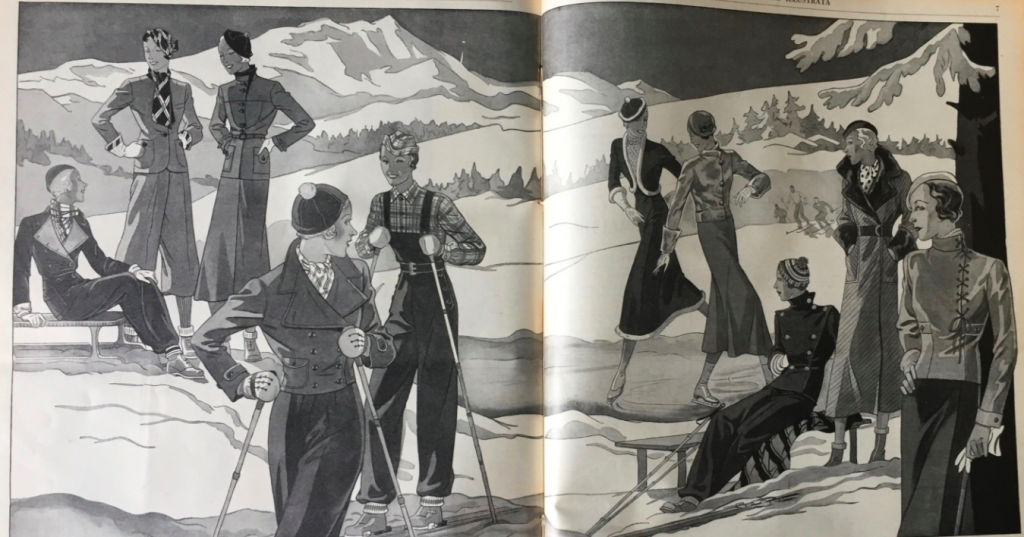

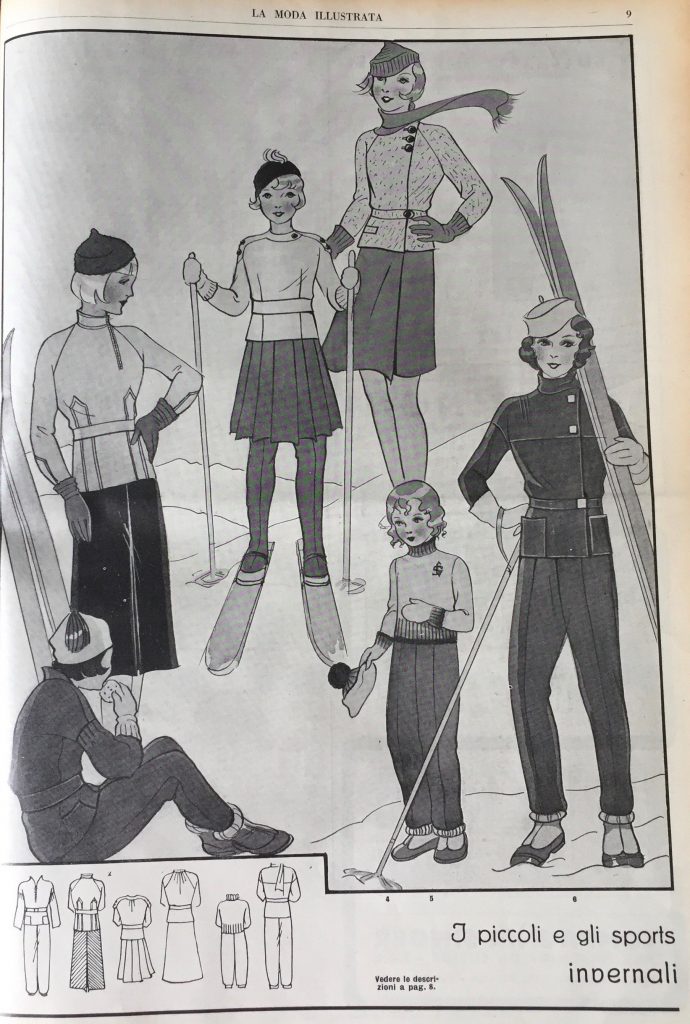

In these fashion magazines there was no place for the concern about ski pants: they were considered the standard sportswear for women’s skiing.

10 women’s winter sports suits (the third wears knickerbockers): the 1st is for sled, the 4th and the 5th for skiing

Source: La Moda Illustrata, 17/12/1933, pp. 6-7

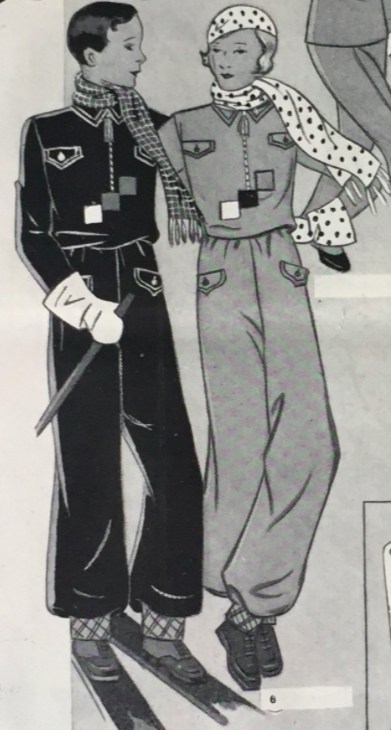

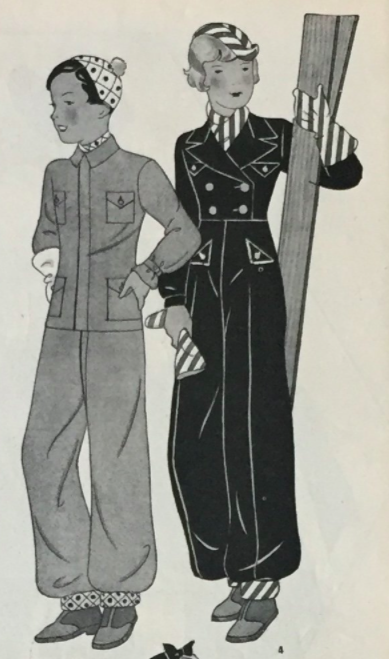

This new woman’s equality was also valid for little girls, as we can see from this model published in the children’s fashion magazines:

Ski suits for 11-years old boys and girls

Source: La Moda Illustrata Dei Bambini, 15/12/1933, p. 2

Ski suits for 11-years old boys and girls

Source: La Moda Illustrata Dei Bambini, 15/02/1933, p. 5

Several models for boys and girls who wear skirts or trousers

Source: La Moda Illustrata, 24/12/1933, p. 9

Also the sledge seemed not to require gendered sportswear …

Compare this model with these picture depicting the Italian Royal Babies on a sledge at https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1417208781096824835

Source: La Moda Illustrata Dei Bambini, 15/02/1933, p. 5

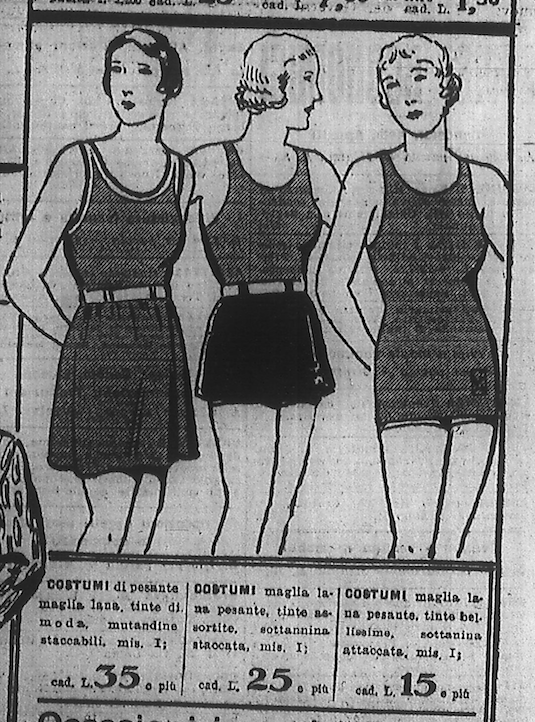

Fashion magazines had no doubt about another topic: no quarter should be given regarding swimsuits. Since they should be ‘decent’ without a low or wide-cut neckline: but a modern wool swimsuit should also be close fitting, leaving the back, shoulders and arms free, to allow for sunbathing – according to La Gazzetta dello Sport

A diving model

Source: La Gazzetta Dello Sport, 25/06/1933, p. 3

An advert by La Rinascente, the most famous department stores in Milan

The first two swimsuit models featured a detachable short skirt

Source: Il Secolo La Sera, 12/06/1933, p. 7

Following the path of wearability, magazines gave some advice to their readers regarding sports underwear: a topic that was completely ignored by all those men writing in sports newspaper about women’s sports …

The use of a onionskin page allowed reader to see what was under the outfits … Source: Vita Femminile, Novembre 1936, p. 25

In fact, the main problem was that men such as the Fascist leaders, sports federation managers, and sports physicians not only choose how Italian women should dress but also freely discussed it, never seeking advice from the women concerned, as we can see in the 1933 controversy about women’s sports between Il Littoriale (the newspaper of the Italian Olympic Committee, CONI) and L’Osservatore Romano (the Catholic newspaper of the Vatican state, written in Italian).

The controversy started on November 6th, 1933, when L’Osservatore Romano denounced what Il Giornale di Genova had published some days before. An anonymous reader wrote to the Genua daily newspaper complaining about the publication of a photo about a local women’s athletic event, protesting that the girls’s outfits were too skimpy. The reader added that those athletes (the only one wearing shorts during the event, while all their opponents wore skirts) were workers implicitly forced to compete by their dopolavoro : if they hadn’t, they probably would be fired. L’Osservatore Romano replied stating that this new kind of women’s sports, advocated by the CONI, was very far from the women’s sports practised in Catholic schools. The problem was in the apparant forcing of innocent and pure females not only to compete in agonistic events, but also to display their body to the audience, pushing them to ‘throw away’ not only javelins but their own modesty.

Source: Giornale di Genova, 31/10/1933, p. 6

Some days later, on November 11th, 1933, L’Osservatore Romano returned to accusing CONI, pointing the finger at photos published by Il Lavoro and FIDAL magazine Atletica Leggera. The attack by the Vatican newspaper is virulent:

There’s nothing worse in sportswear than the tight-fitting sweat pants that replaced short skirts, and the swimsuit-like outfits that replaced the traditional corset. There’s nothing more devoid of grace than the behaviours and muscularity that are more longshoreman-like than masculine. There’s nothing more repugnant than those flushed faces, the hair blowing in the wind, that Medusa hairstyle.; there’s nothing more ridiculous than shrunken, stretched, or writhing bodies [during athletic competition]; there’s nothing more obscene than the sbracato [meaning both ‘without trousers’ and ‘vulgar’ in Italian] leap that the photographer was successful in capturing, in a sort of satirical malignant insult. There’s nothing more pitying than such a shameless show, served to the audience’s comments and jokes!

L’Osservatore Romano then asked: given that the ancient Romans, who were pagans, were horrified at allowing women to enter the stadium, what was likely to be the attitude of a Catholic regime that was proud of its Roman legacy?

Athletes form the Genua region

Source: Il Lavoro, 09/11/1933, p. 6.

The Italy National team defeated by the France National team

Source: Atletica Leggera, 15/01/1933, p. 8

After two further articles by L’Osservatore Romano, Il Littoriale replied on November, 22th 1933, with a famous editorial entitled ‘Dell’attività sportiva femminile’ (On Women’s Sporting Activity). CONI claimed its control over the Italian sports movement: meant that women’s sport had never turned into a sideshow … the recent boycotting of women’s football was brought as an example of such control!

The controversy continued, until mid-December: L’Osservatore Romano went on accusing women’s sportswear of being indecent, and the Fascist CONI of misleading the Italian females; on the other hand, Il Littoriale suggested that the sin was not in the athletes’ naked legs, but in the eye of those (very few) lecherous men who attended women’s sports events. Other newspapers, such as Il Mezzogiorno Sportivo and Lo Schermo Sportivo, entered the controversy, but to a lesser extent. The second wrote accusing the morality of the Italian sports press, writing that ‘there’s a champion, called Ondina [Valla]: every newspaper would pout if it couldn’t publish each month picture of her in several poses, even legs astride during the jumps’.

Ondina Valla during an high-jump event

Source: http://www.ondinavalla.it/la-storia/latleta/

Italian athletes Ondina Valla (3rd from the left) and Claudia testoni (5th) during the 80ms hurdles Olympic final in Berlin (1936)

Source: http://www.ondinavalla.it/foto_categorie/

An older Ondina Valla and the statue ‘L’ostacolista’ that her brother Rito, who was a sculptor, dedicated to her. As you can see, the main difference is that the women sculpted is wearing a skirt! The statue has a controversial history: originally it was situated at the Gioventù del Littorio (the Youth Fascist association), and then in front of the Valla’s house in Bologna. As Ondina herself said during an interview, after the fall of the Fascist regime someone perceived this statue as being linked with it, so it was removed. Some time later, it was purchased by local businessman Capigiani, who then placed it in front of his icecream company headquarters.

Then finally, on December, 12th, 1933, when the controversy was coming to an end, Il Littoriale gave concerned readers the chance to say something: it published a letter written by an unidentified group of Giovani Italiane, from a city in Lombardy – probably Pavia, Mantova, Lodi or some other medium-sized urban centre built upon a river or a lake, because they included the fact that they practiced rowing. Those brave women, who identified themselves as sporting, Catholic and Fascist women, wrote that they decided to write a letter to Il Littoriale, because they felt outraged: how could the male journalists of L’Osservatore Romano argue and write about women’s sports, since they were neither women or sportsmen?

Talking about the sportswear (that was just one topic of the wider controversy), the Giovani Italiane wrote:

We would never say that sport was negative for us, even if we wear shorts, in order to improve our freedom of movement. The fact is: when we jumped in skirts, often the horizontal bar fell down….

For these women there was no debate to be entered into, since no issue regading decency was more important than the sporting performance. Then, answering L’Osservatore Romano who pointed the finger to the lecherous men, the Giovani Italiane suggested that the solution wouldn’t be to abolish women’s sporting events, but perhaps to ban a male audience: firstly because athletes needed a supportive audience to gain better performances, and secondly because such performances could be inspirational to some women in the audience. These two short passages are the only ones about sportswear in a very long letter, which is not really surprising. In fact, it shows us a very important point regarding sportswear, which is: it is not the problem of the female athletes, but rather of the male audience. For the Giovani Italiane, the performance was the main criterion, not the dress.

Piccole Italiane with clubs, in Gioia Del Tauro

Source: Collezione Cesare Gabriele, https://bit.ly/3oGcQCN

The 1933 Giovani Italiane’s letter is a very rare case of women’s opinion being publishing concerning their own sportswear in Fascist Italy. A further interesting case, from the same year (1933) and region (Lombardy), is not about what some women thought, but rather about what they did by themselves in order to improve their own sportswear.

On Sunday, April, 30th 1933 the Provincial ONB Woman’s Athletics Championship, called Pentathlon della Grazia, took place in Milan. Piccole and Giovani Italiane from all the local schools gathered at the campo Giuriati to compete in running(40ms for Piccole Italiane, 50ms for younger Giovani Italiane, 60ms for older Giovani Italiane), ball throw, archery, javelin, balance beam, and high jump events. The girls were divided into 3 categories, and a lot of parents attended the competition to support their daughters: the ONB trainers ensured that there was no-one else on the stands.

Some girls during the Pentathlon della Grazia … wearing skirts

Source: La Gazzetta dello Sport, 04/05/1933, p. 4.

The previous edition (81932) of Pentathlon della Grazia, in Milan

Source: Bollettino del Comitato Provinciale di Milano, 15/05/1932, p. 1.

The event was a big success, the organization was perfect, but … thanks to the newspapers we know what unexpectedly happened on the field. As La Gazzetta dello Sport wrote,

all girls wore the ONB uniform, composed of a blue skirt, white blouse and beret. But those who were really willing to win used a trick, in order to get rid of the skirt. They fastened it at one side, and then, at the last second, they opened the fastening, revealing a pair of shorts, these athletes were agile while running and faster during the throws and jumps

Some newspapers published the picture of this clever trick, probably because it was considered as a childish caper, or maybe because some journalists, deep down, approved of this brave and unconventional decision. It could also be implied that the ONB managers thought the same as they didn’t try to stop this happening … but neither did they suggest that the skirts could be left behind!

Two winners (running, and javelin), in shorts … all around, others competitors are wearing long skirts

Source: L’Ambrosiano, 01/05/1933, p. 8

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 07/05/1933, p. 4

In conclusion: women’s sportswear appears to be a interesting field of study, especially the Fascist rule over women’s bodies during the Ventennio. Italian females were not free to wear what they wished, they had to follow the guidelines of the regime or, for the most part, of the specific federations, which insisted they cover their bodies, fearing the sexual power on the male audience. On the other hand, the regime couldn’t be so reactionary, because its donna nuova was a modern woman, active, sporting and expected to move outside the very home in which her older sisters, mothers and grandmothers were tethered to: it made some concessions to the demands for modernisation coming from the Italian society, which were fulfilled by fashion magazines. A second key-element of the Fascist policy was the relationship with foreign states: not only off the field (i.e. the Hollywood sporting divas model), but above all on it, so international competitions. Sometimes Italian athletes adapted their sportswear to the one worn by their opponents; sometimes they marked the difference (i.e. the basketball skirt worn in Euro38). Since the athletes were not consulted, up to now we can’t say almost anything about what they thought of their own sportswear, or about what they wished to do about it: yet a few documented examples such as the letter from the Giovani Italiane, or the making of the GFC football skirts, show us how much this subject could be fruitful for historical research.

Article © of Marco Giani

For more images about the Pro Patria athletes, see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1421514286808064004

For more images about women’s sports fashion in the 1930s’ Italy press, see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1120360397364781059

For more Hollywood divas practising sport photographs published by the 1930s’ Italian press, see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1020331217386917888

For more images about Piccole and Giovani Italiane uniforms, see:

https://sorelleboccalini.wordpress.com/le-fonti_il-fascismo-femminile-strutture-e-simbologia/

For more image about the 1932/1933 controversy about women’s ski pants, see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1021084969014308864

For more image about the controversy about the women’s tennis outfit, see

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1041361147323195392

For more images about Italian Princesses and sports, see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1019676244324077569

For more images about the sportswear of 1933 Gruppo Femminile Calcistico footballers, see:

https://sorelleboccalini.wordpress.com/extra_gfc_le-divise-delle-calciatrici/

For an article (in Italian) about the 1933 controversy among Il Littoriale and L’Osservatore Romano, see

For an article (in Italian) about the representation of sportswomen’s body by the 1930s’ Italian press, see:

https://doi.org/10.34102/italdeb/2018/4667

For an article (in Italian) about the 1933 Giovani Italiane’s letter, see: