The author would like to express thanks to Luigi and Francesco Ferrari for the images (taken from Archivio personale Giovanna Boccalini Barcellona), and to Alice Vergnaghi for her help with the interpretation of the historical images.

PLEASE NOTE – Express permission is required to reproduce ANY of the images in this article – please contact Playing Pasts or the author for more details.To read the previous articles in this series please see the links below

Part 1 – bit.ly/2NBMzZg Part 2 – bit.ly/2JKczw6 Part 3 – bit.ly/38ACGl8

Part 4 – bit.ly/36AWHWA Part 5 – bit.ly/2vo8I4P Part 6 – bit.ly/2KwU3Zf

As Playing Pasts readers already know [see https://bit.ly/30YWk8i ], Giovanna Boccalini [1901-1991], wife of accountant Giuseppe “Peppino” Barcellona [1898-1980], and above all mother of Olympic ice-skater Grazia Barcellona [1929-2019], had a central role inside the organization of Gruppo Femminile Calcistico [GFC], since she was the commissaria of the team. Although it’s not 100% clear the exact historical meaning of this term, we can argue that she was a kind of assistant manager, since both GFC President Ugo Cardosi and Piero Cardosi [Ugo’s son and first coach of the team, who was later replaced with Umberto Marrè] were male, and a woman, able to assist the female players in the locker room, was required. Giovanna, a former accountant who worked as an elementary school teacher and mother of two children, namely Giacomo “Popi” [b. 1926] and Grazia [b. 1929], and, perhaps more importantly, older sister of three calciatrici ‘footballers’ Luisa “Gina” [b. 1906], Marta [b. 1911] and Rosa “Rosetta” [b. 1916], was just perfect for this position.

Giovanna as “commissaria”, her sisters Luisa and Rosetta as footballers.

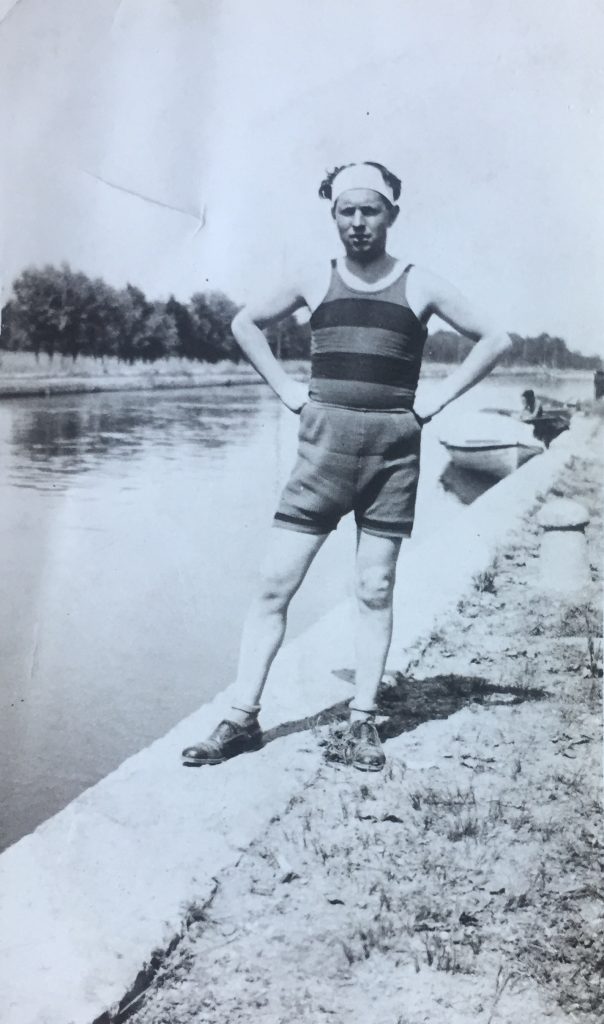

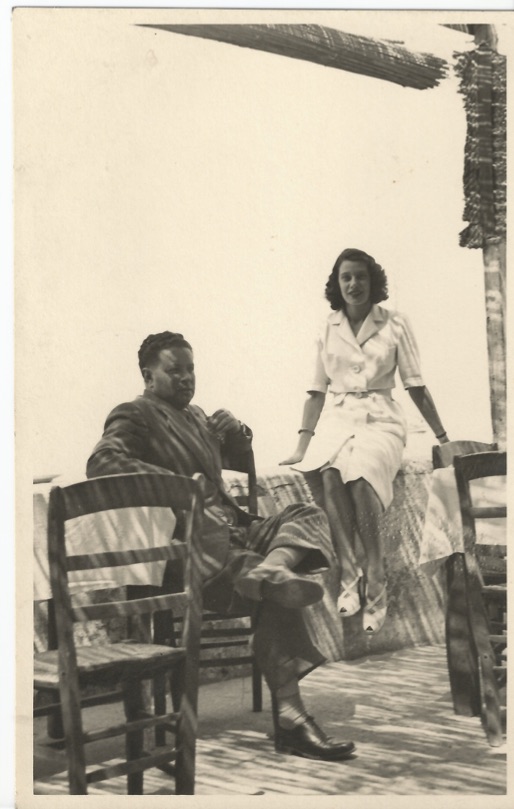

Since the photo was probably taken in May 1933 [it has the same building on the background of the 3rd photo published in http://bit.ly/35jX8V5 ] the man may be coach Umberto Marrè, who had played as a professional footballer in middle 1920s.

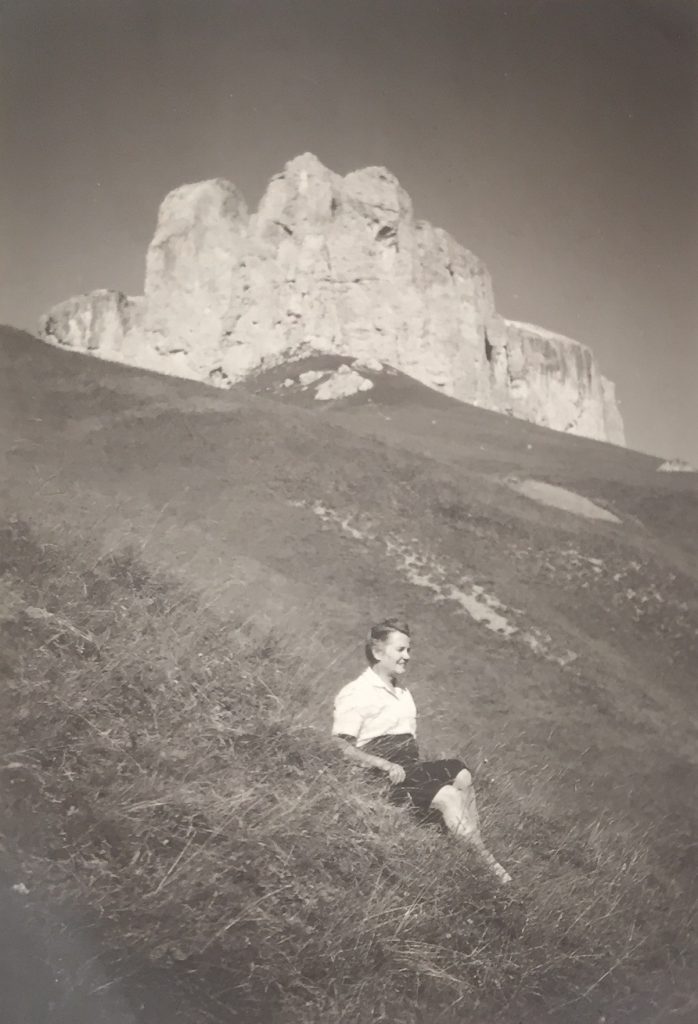

Giuseppe and Giovanna in swimsuits

As we can read in a May 1933 interview, published by sports weekly Il Calcio Illustrato, Giovanna’s favourite sport was hiking. Journalist Carlo Brighenti, who had previously stared suspiciously at the woman who yelled against the referee during the GFC match, ‘forgave’ Giovanna’s lack of respect, mainly because of her answers to his questions about the sport she liked the most. Giovanna told Brighenti that she loved the mountains so much, and that she had already climbed Cimon della Pala [a famous Dolomiti peak]. Then she praised calciatrici‘s perfect discipline, the team respected the referee’s instructions [something that Italian male football teams lacked during those years, despite all the efforts of the Fascist regime], as well as their pure and selfless passion for the game. In Giovanna’s opinion, football was ‘a very ethical sport, very useful to build girls’ characters, will, and courage’. Almost certainly Brighenti didn’t know about Giovanna’s political faith, during her youth in Lodi, she was a fervent Socialist thanks to her friendship with Ettore Archinti [see https://bit.ly/30YWk8i ], during those 1933 Spring days when her husband was arrested by the Fascist political police.

Giovanna in the courtyard of her house, in Piazzale Dateo [1933]

she sent this photo to her husband Giuseppe, who was confined to the Tremiti Island, in the middle of Adriatic Sea.

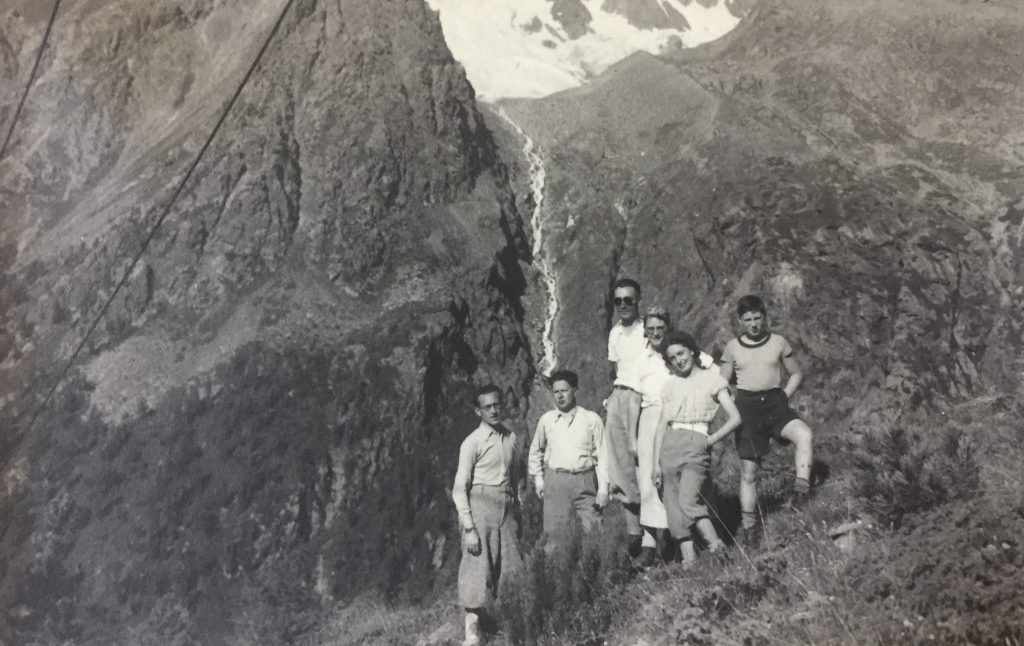

Giovanna and some relatives during a mountain trip

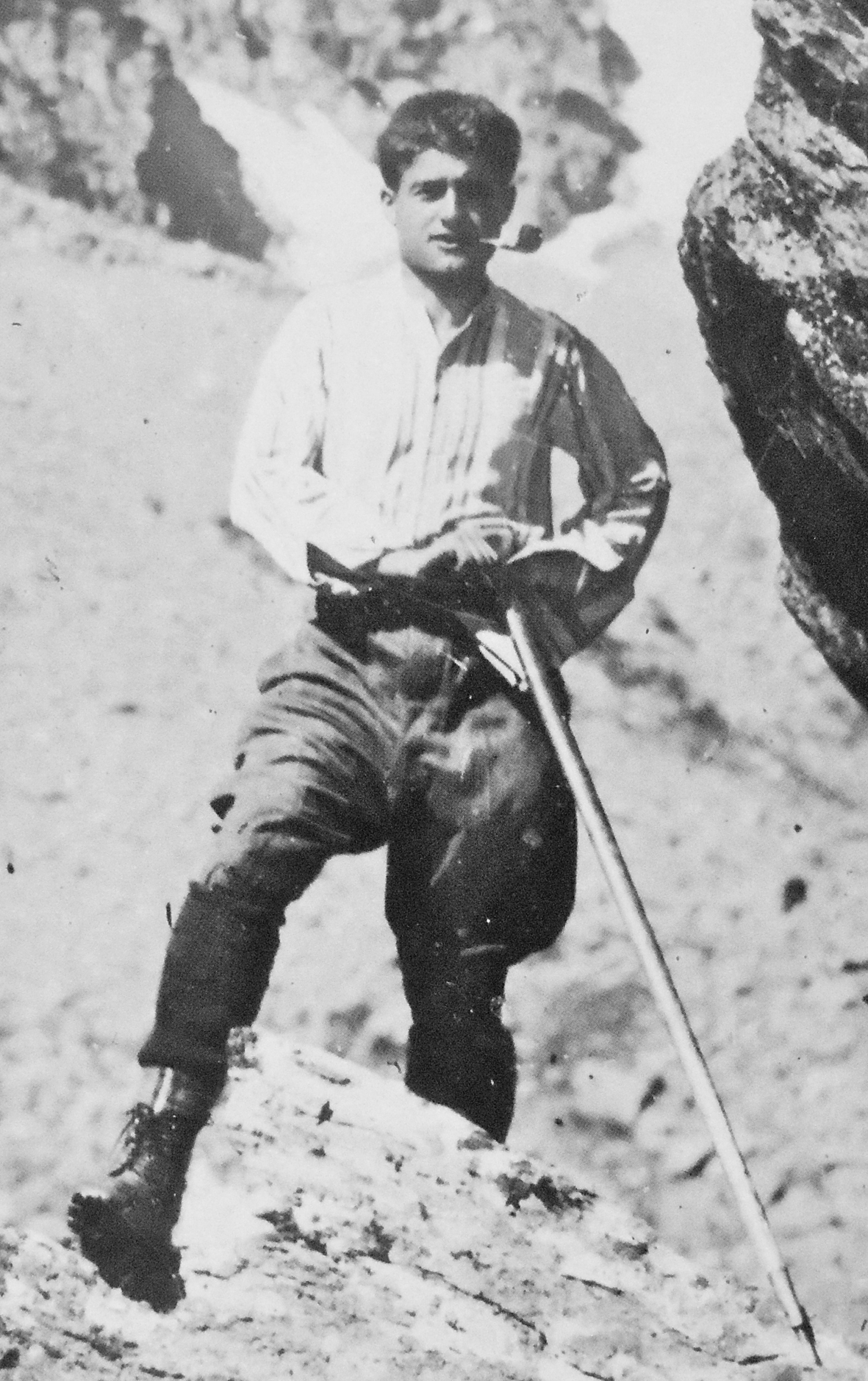

Giovanna’s love for hiking came as no surprise, Socialist and even Catholic movements had a strong diffusion of this leisure activity before the rise of the Fascist dictatorship in the mid-1920s. Above all, hiking was one of the few sports that men and women could practice together with no ‘moral scandal’, such as was witnessed by the story of Pier Giorgio Frassati, the young Catholic activist, who died somewhat prematurely in 1925. As everybody in Italy knew, Pier Giorgio’s group of friends with whom he shared his Catholic faith and his love for the mountains was a mixed group. Mixed-sex alpinist societies existed even in the Socialist movement in Northern Italy, including in Milan.

- Pier Giorgio Frassati, the alpinist Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fc/PierGiorgioFrassati-Alpiniste.jpg

-

Pier Giorgio Frassati with his male and female alpinist friends

Source: https://bit.ly/3iJggCf

A lot of photos in Giovanna’s archive are proof of her love for hiking, a passion also shared with all the members of Barcellona-Boccalini family

-

Giovanna with two female friends, in the middle of the snow

Note the hiking boots, and the ice-axes

-

Giovanna with her son Popi, her brother-in-law Calogero Barcellona [1st left] and Calogero’s wife Ilia 1st right]

Note that everybody are dressing hiking boots

A friend, Giuseppe Barcellona, Mario Boccalini [Giovanna’s older brother], Giovanna, Francesca [Mario’s daughter], Popi

Mario Boccalini, Giuseppe Barcellona, Francesca Boccalini, Giovanna, Popi, a friend

Note the white long skirt worn by Giovanna, opposed to the trousers that her younger nephew Francesca [b. 1921] is dressed in

Giovanna and a friend

Note the trekking stick

Giovanna and Giuseppe shared their love of the mountains not only with relatives, but also with friends.

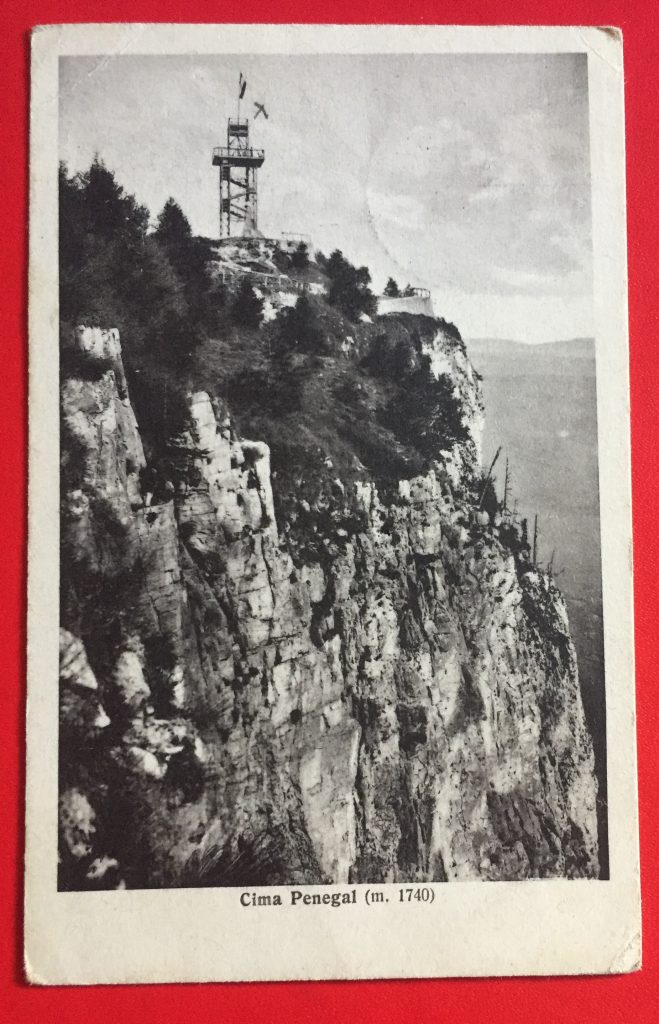

- The postal card they sent to Rosetta from Cima Penegal [Summer 1936]

- Giovanna, Popi and Giuseppe [in the middle] with a family of friends, during a walking

Giovanna [1st], Popi [2nd] and Giuseppe [4th] with some friends in Cima Penegal [Malorco, 1936]

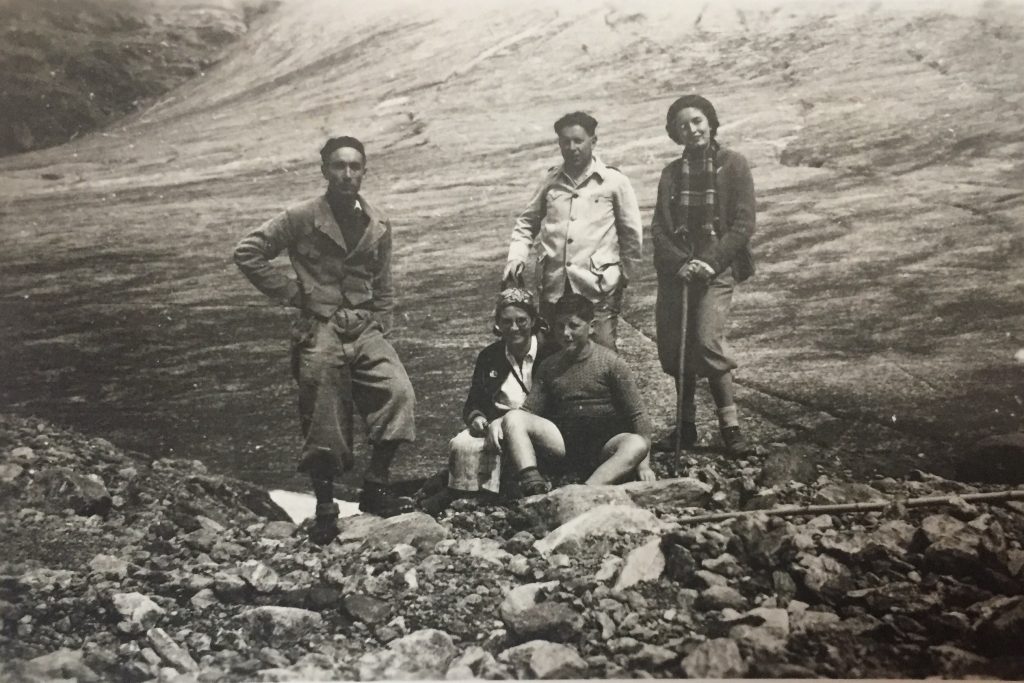

- Giovanna, Popi and Francesca in front of the glacier

- Francesca, Popi, Giuseppe, Giovanna and Mario

- Another image from the trip

- A modern image of the Careser pike Source: Wikipedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cima_Careser.jpg

At the end of the climbing, they had some lunch: cans, and a bottle of wine!

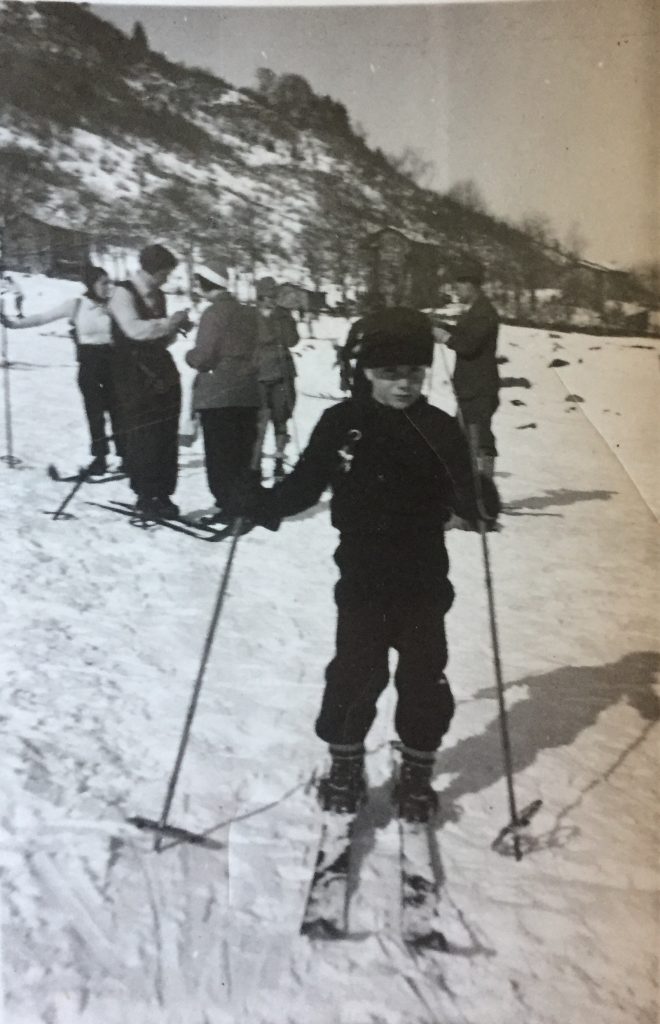

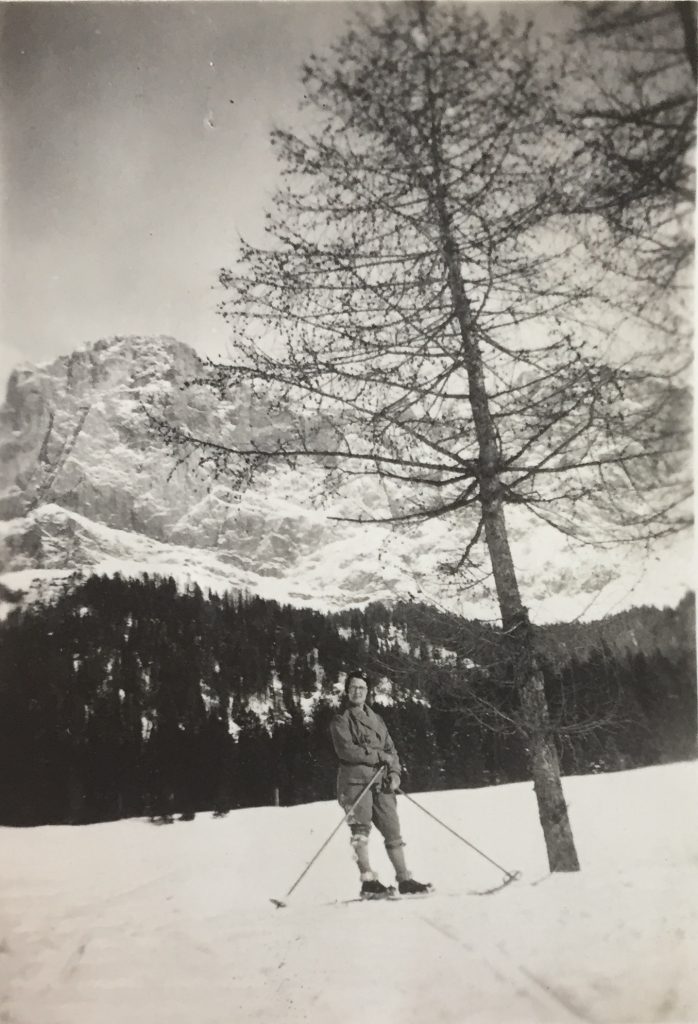

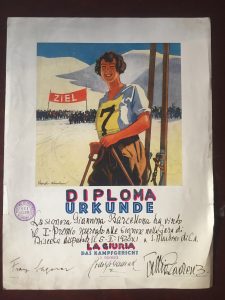

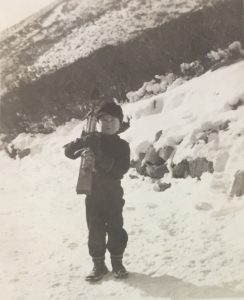

Skiing was the other main sporting activity that Giovanna seemed to have practiced for a long time and with both her male and female friends, eventually introducing her son Popi to the activity. Like hiking, there was no social prejudice against women skiers, and they could practice alongside their male relatives and friends, as we’ve already seen with Brunilde Amodeo’s photos [see https://bit.ly/2yKHIOL ]. Just like Brunilde, Giovanna used to ski in Pian Rancio, near Lake Como which at that time was a popular place for Milanese tourists.

Giovanna, in white, on the right, with some friends.

Giovanna and Giuseppe with some friends [Pian Rancio, 1930]

- Popi practising in Pian Rancio [1931].

- Giovanna skiing with some friends

Giovanna [2nd], Giuseppe [6th] and Popi [7th] with some friends at Pian Rancio [Winter 1931/1932]

- Giovanna skiing

The 1st place diploma for the 1933 amateur ski event for married women in San Martino di Castrozza [Dolomites]

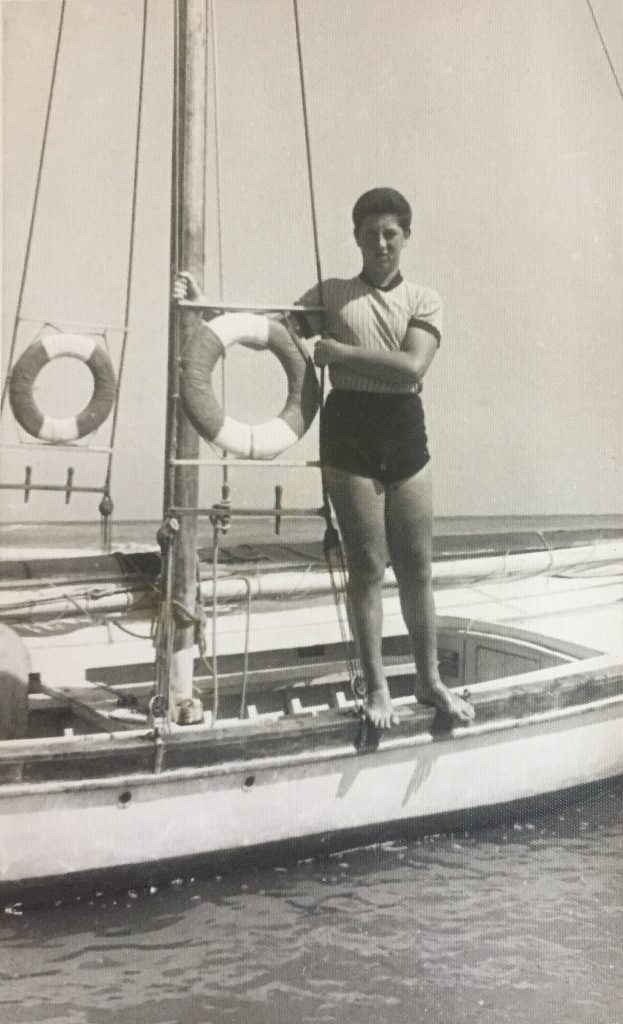

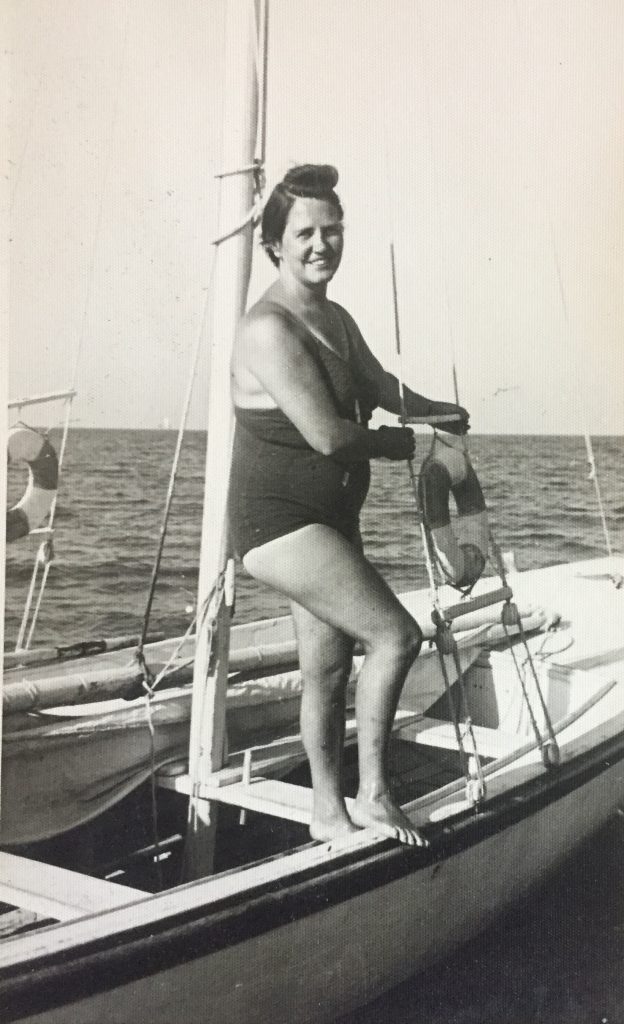

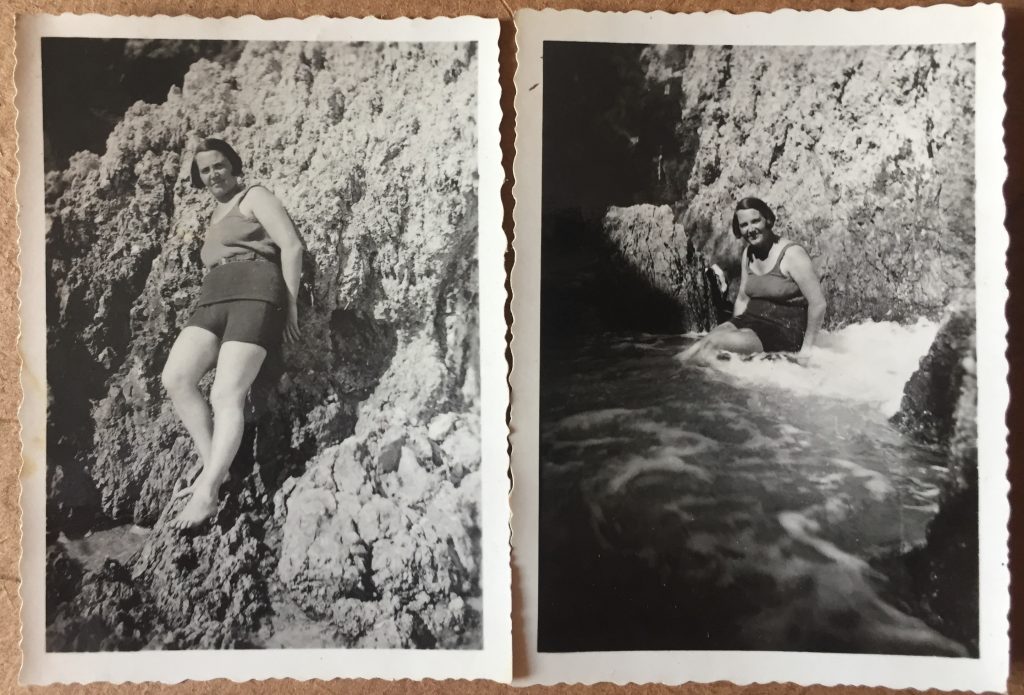

Giovanna in swimsuit

Further to this, they also informed us that Giovanna had a driving licence, which was not so common for women at that time, while Giuseppe didn’t hold such a licence.

Giovanna with some friends in front of a car.

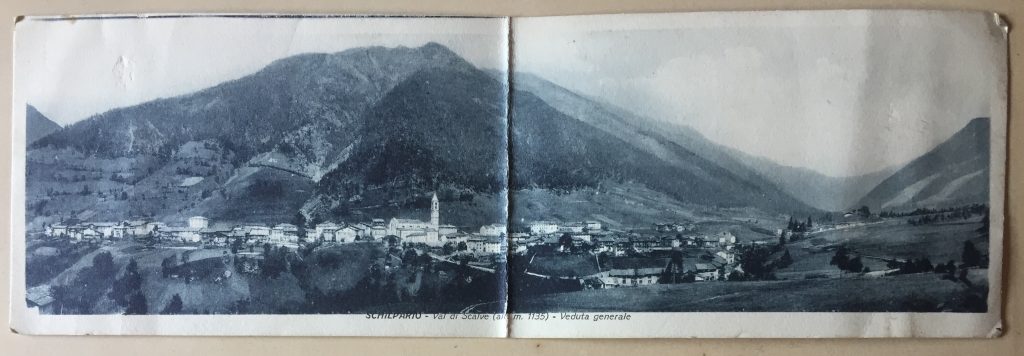

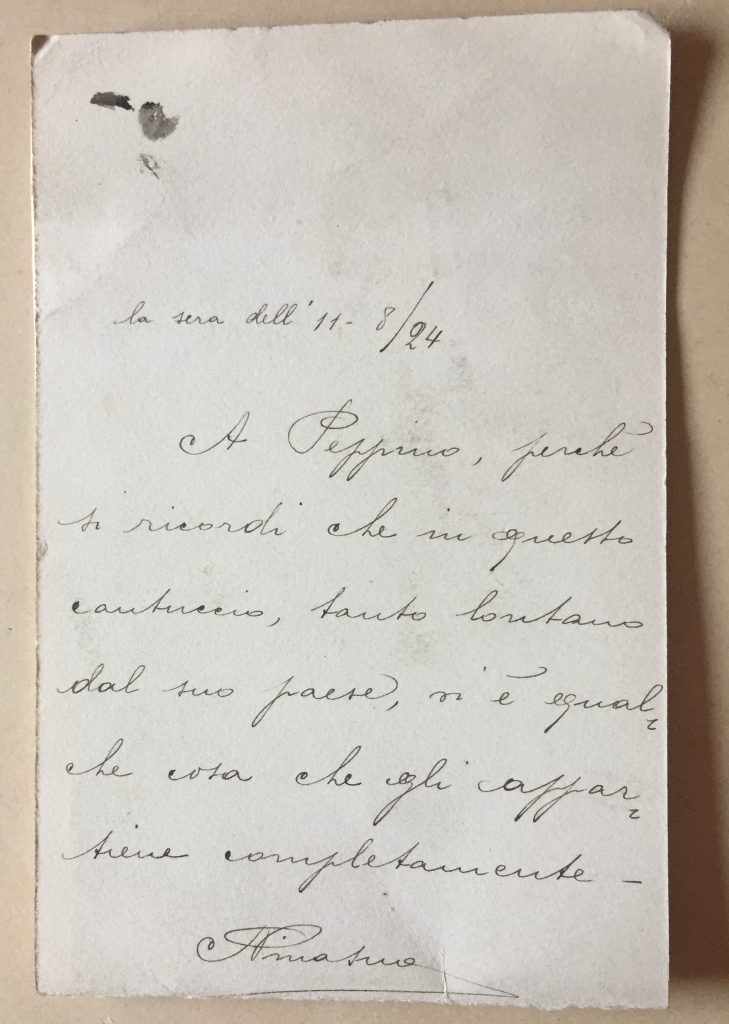

With Giovanna being the more actively sporty one of the couple, it was she who probably introduced Giuseppe, an immigrant from Siracusa [Sicily] to the Alps, as can be seen by this 1924 post card from Schilpario, a little village in the Bergamo mountains. The couple went on to marry a year later in Lodi.

“Evening of 11th August 1924

To Peppino [Giuseppe’s nickname]

so that he could remember that in this corner, so far from his homeland,

there’s something that totally belongs to him.

Your Nina [Giovanna’s nickname]”.

A young Giuseppe [10th from left, in the 1st row] with some friends: two of them are holding bowls

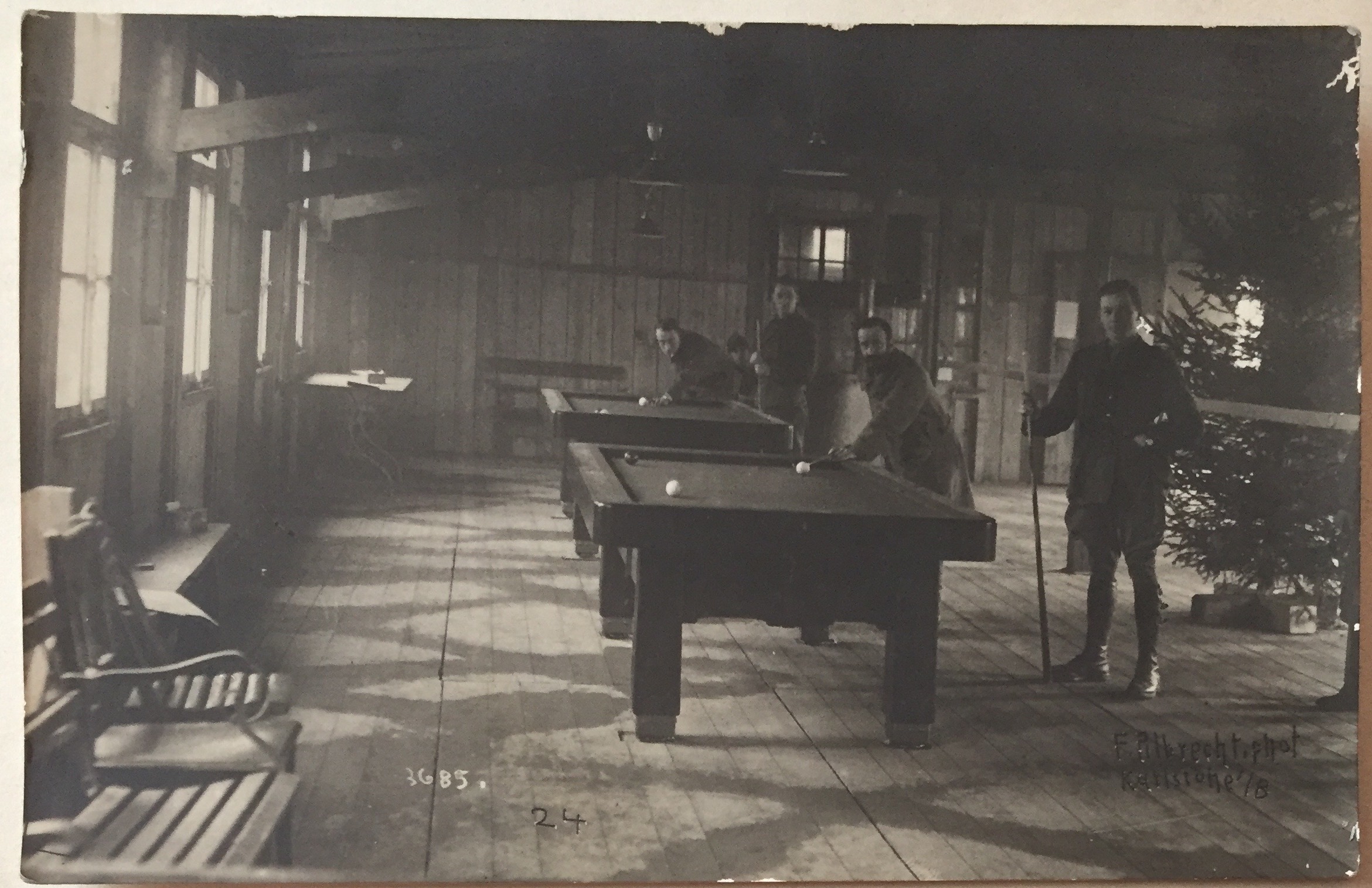

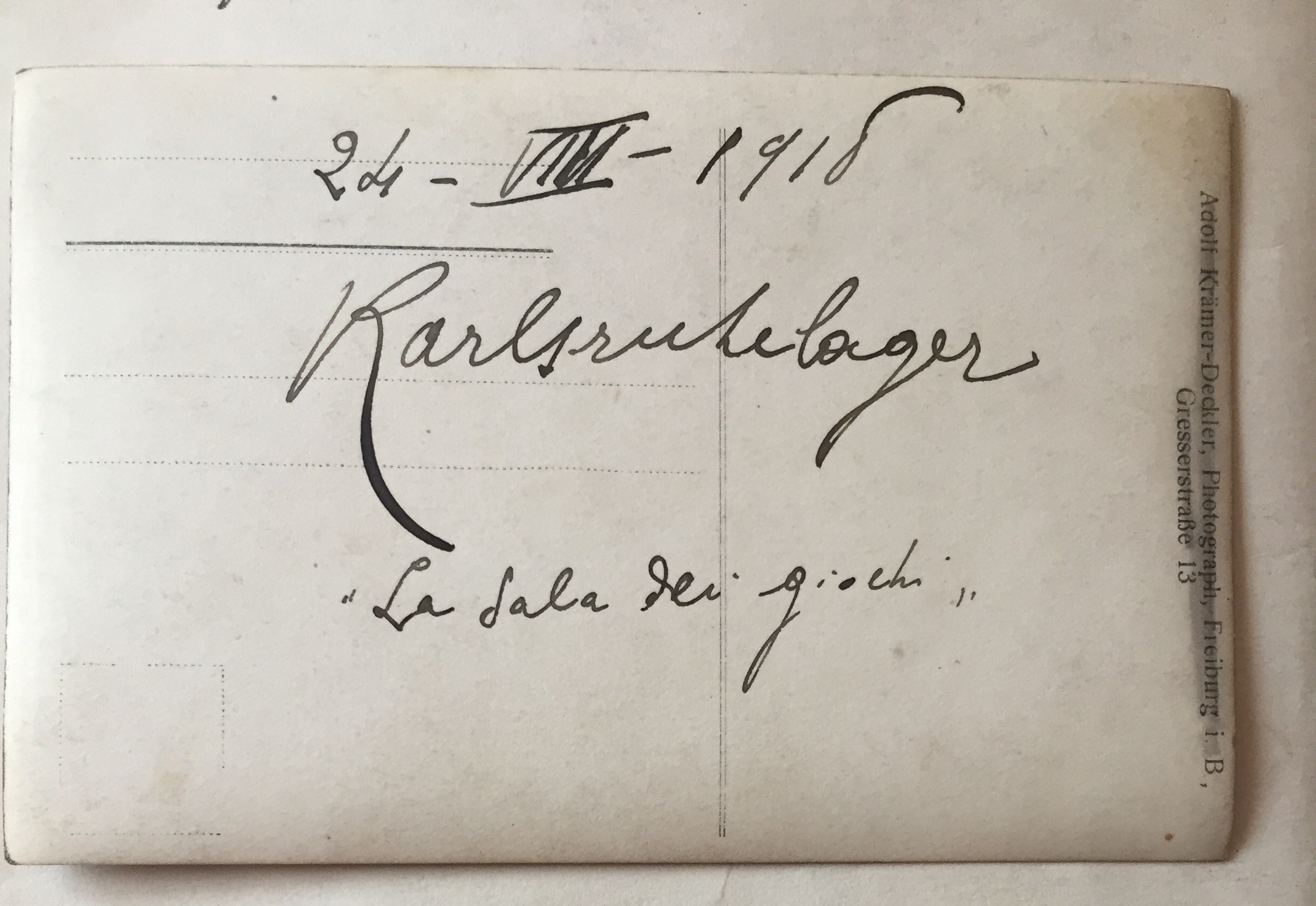

A 1918 post card by Giuseppe as prisoner of war. He was captured in the Alpine Front by the German army, and then sent to the Karlsruhe lager. Giuseppe ironically describes the room with a billiard as the‘ sala da giochi’ or games room

Some pictures dating to the first years of their marriage show Giovanna and Giuseppe during boat trips, riding bicycles, and smiling in front of tennis courts.

- Giovanna with 3 female friends, on a boat. Giuseppe is the man, kneeling on the right

- A friend riding with little Popi, and Giovanna [Corsico, 1931]

Giovanna in a boat at Canottieri Olona headquarters [Milan, 1931]

Giovanna, Giuseppe [rowing], a very young Grazia, and Popi

Milan, June 1931

Giuseppe in a rowing outfit, Giovanna in white and some friends

Please note Giuseppe’s ‘stylish’ shoes!

Giovanna [4th] and Giuseppe [5th] with some friends

Note the tennis court in the background

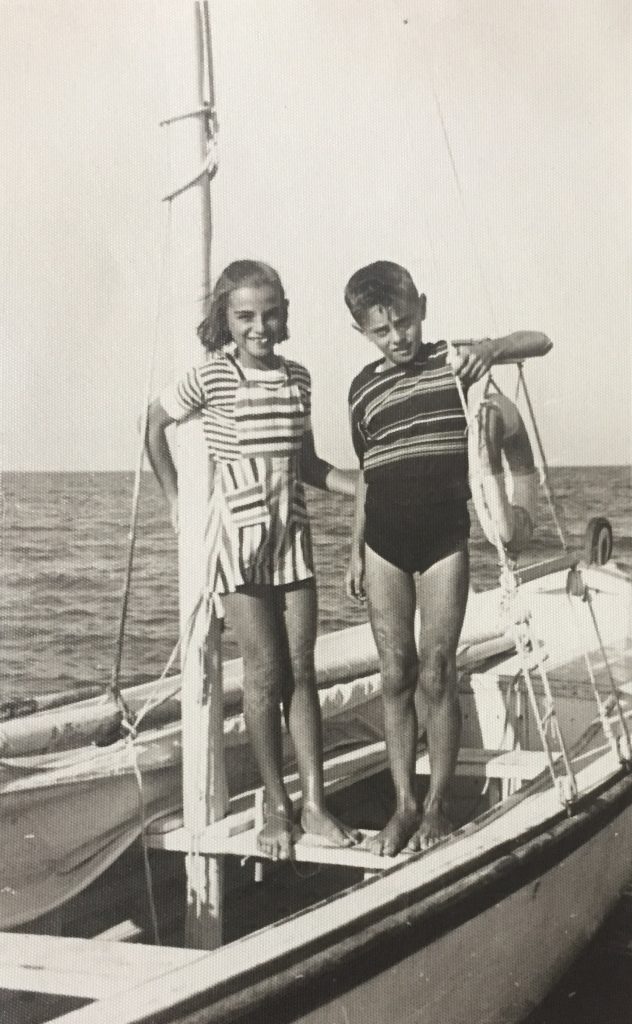

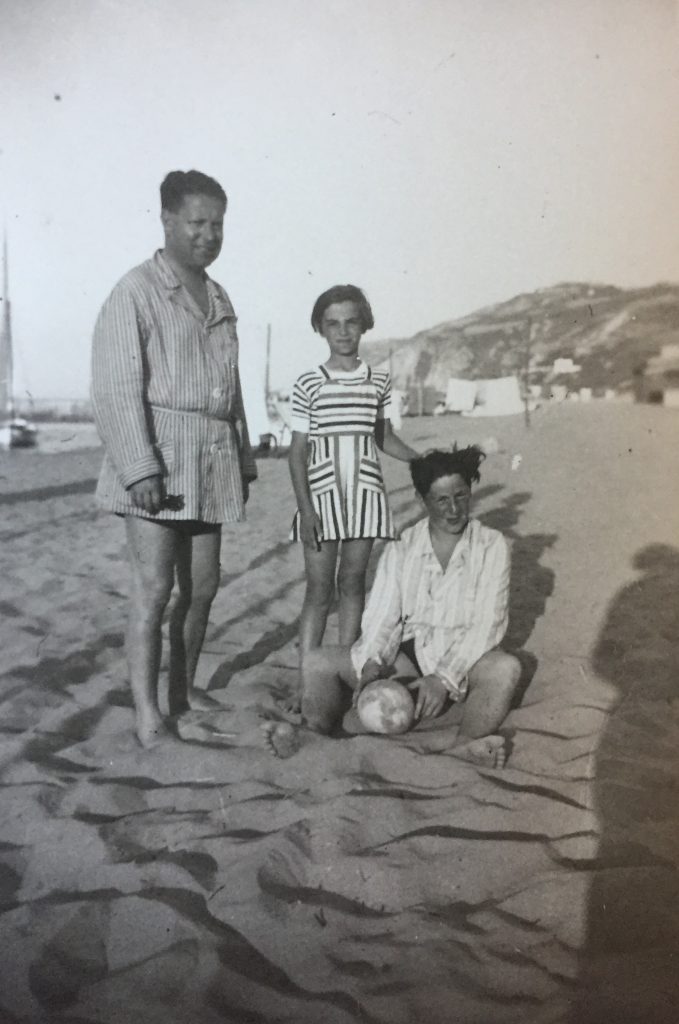

Giuseppe, Grazia and Popi, with a ball [Gabicce, 1939]

-

Everybody was sailing, in Gabicce, 1940

Giovanna; Popi; Grazia and a friend

Grazia playing with a ball.

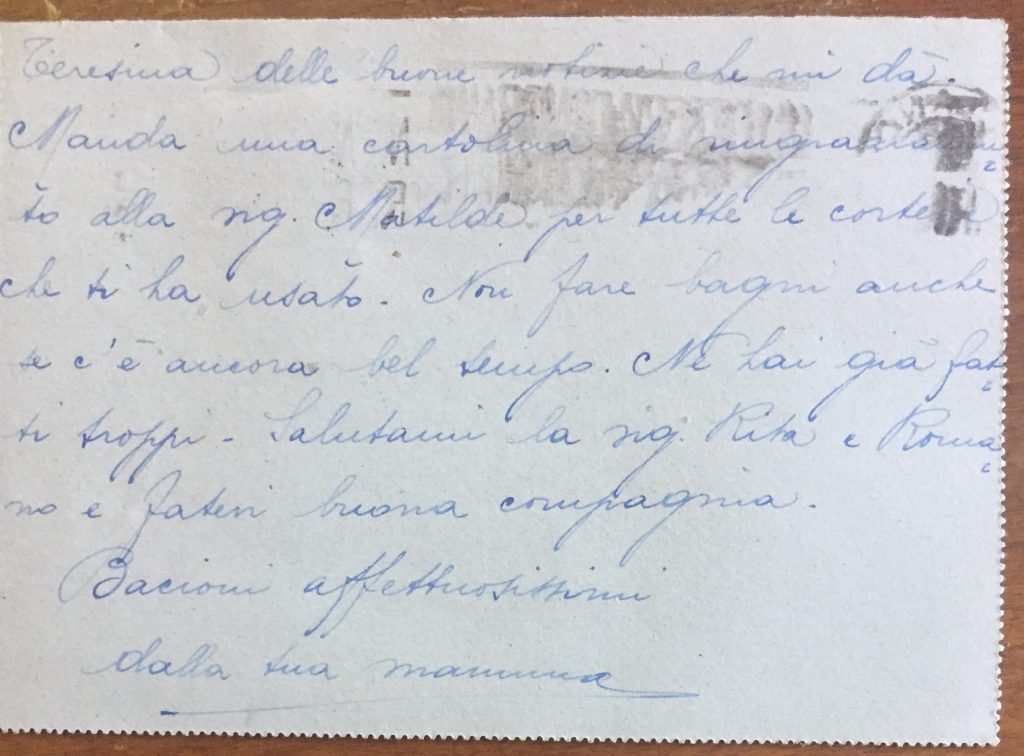

In this postcard, written in Summer 1940 to the 11-year old Grazia, who was staying at the seaside with her nanny Teresina

Giovanna writes:

‘Do not take a bath, although the weather is still fine: up to now, you did it too much!’

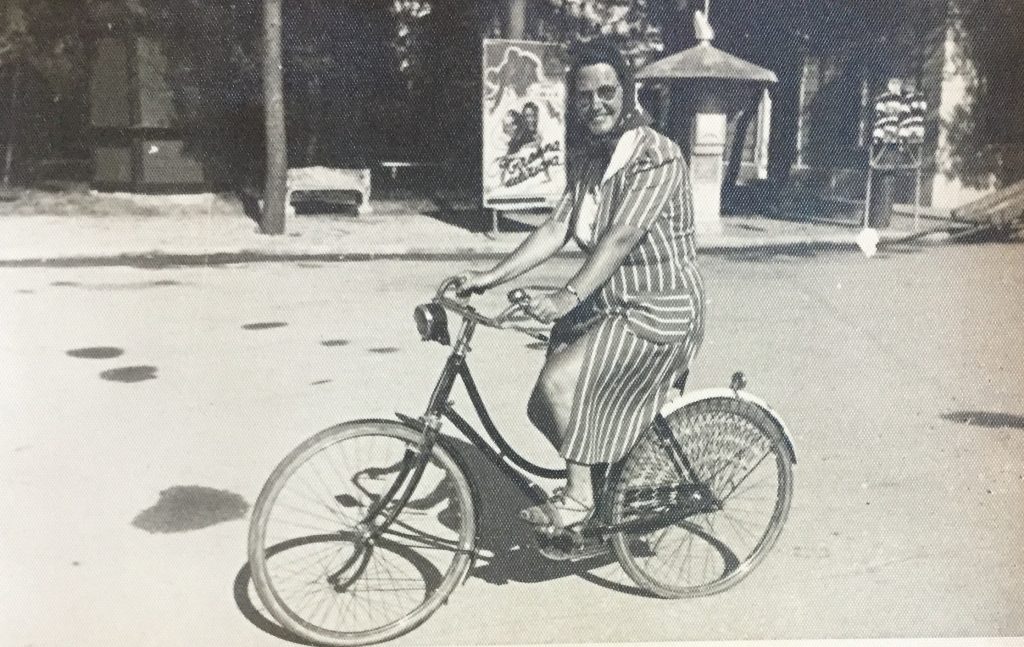

A lot of pictures from summer holidays in late 1930s and early 1940s show the three Boccalini sisters cycling:

- Giovanna cycling

- Marta and Giovanni riding a tandem

- Rosetta, Popi and a couple of friends [Riccione, 1939]

- Marta, Giuseppe, Rosetta, Giovanna, Grazia and their bycicles [Riccione, 1941]

Grazia cycling [Cattolica, 1940]

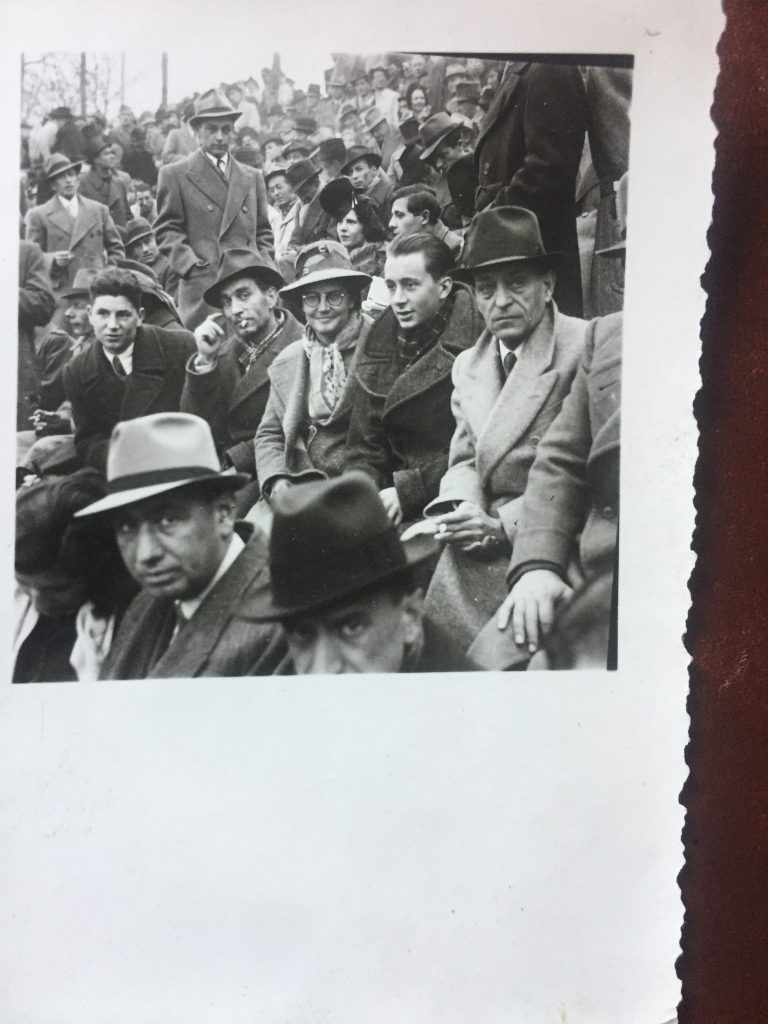

Young Giovanna and Giuseppe attending a [football?] game

Older Giovanna and Giuseppe [on the right] attending a [basketball?] game

-

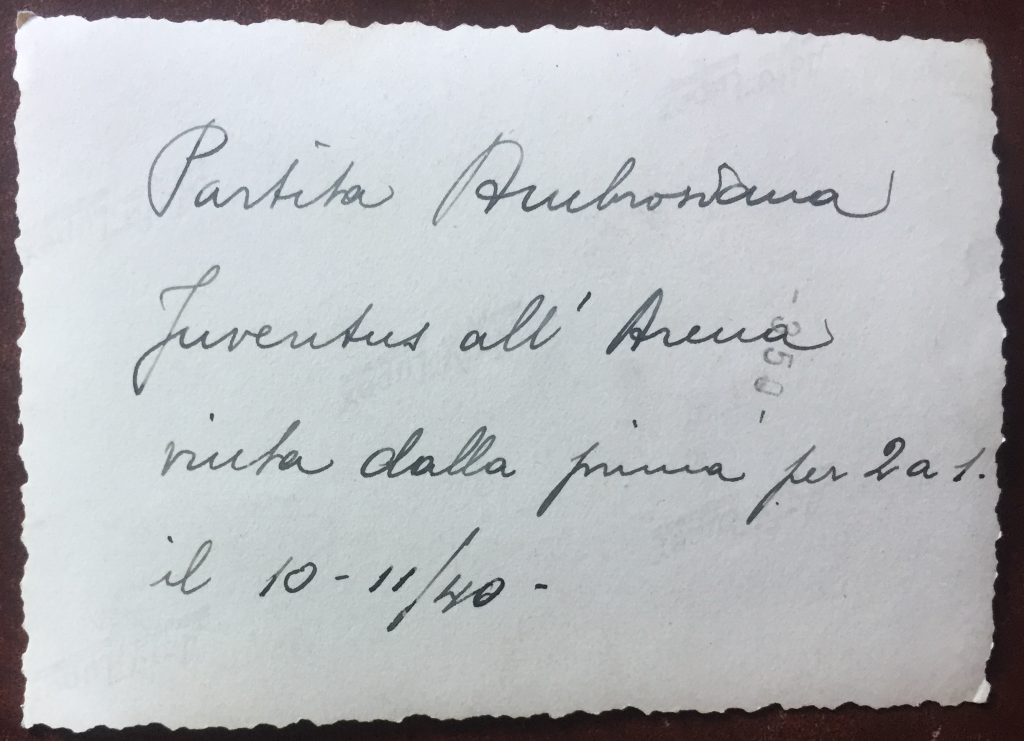

Readers of Playing Pasts already be familiar with this beautiful picture, a copy of which is kept in Marta Boccalini’s archive [see https://bit.ly/30YWk8i ).

Now we can read the original caption:

‘Match Ambrosiana Inter – Juventus, played at the Arena, won by the first team 2 to 1, on 11 October 1940’.

Thanks to this chronological element, we can argue that this photo, which shows Popi, his uncle Mario Boccalini, Giovanna and a friend, was taken for Giuseppe, who was serving in the Italian Army in Northern Africa.

One of the features noticed when viewing Giovanna’s photo archive is that, thanks to Giuseppe’s apparent laziness and his open-mindedness, he seemed to have left the ‘sporting education’ of their two children to his wife. It is a good thing here to be mindful of the fact that the figure of a ‘sporting mother’ was quite revolutionary in 1930s Italy; at that time, girls used to ask the permission of their father in order to practice sport, knowing that most mothers tended to be more conservative in their views about female sport. Giovanna herself took care of not only Grazia’s sporting education but that of Popi as well!

Popi and his little friend Pepi having a talk during the sleeping hour at Colonia Igea [Summer 1930]

Colonia Igea, which was founded in Romano di Lombardia, before the Fascist regime, became the Ventennio a “colonia elioterapica”

The regime was trying to spread among Italian youth the habit of sunbathing for medical reasons.

- Popi and her mother [Zambla Alta, 1932]

- Popi learning to ski [Pian Rancio, 1931]

A friend ]1st] Ilia Barcellona [2nd] and … Giovanna watching over what Popi was doing!

Zambla Alta, 1932

Popi learning to take his own skies [Pian Rancio, 1932]

Popi and his friend Pino, swimming

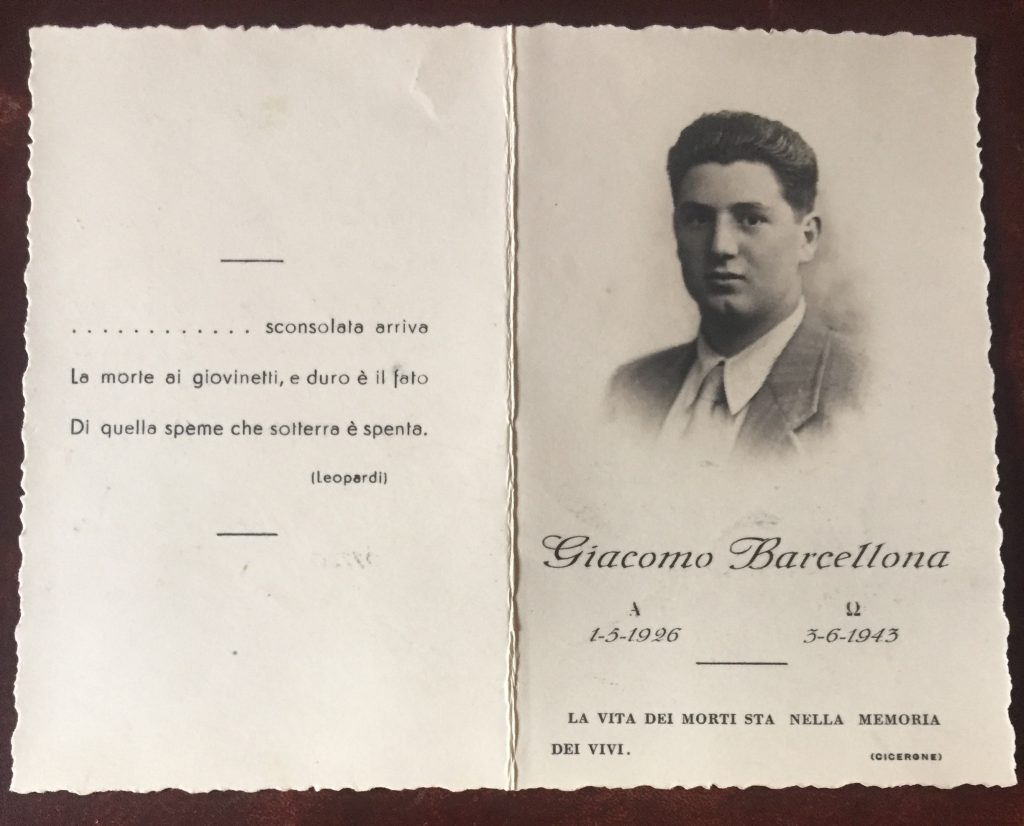

Taken in Summer 1942, it is one of the last photos of Giovanna’s son

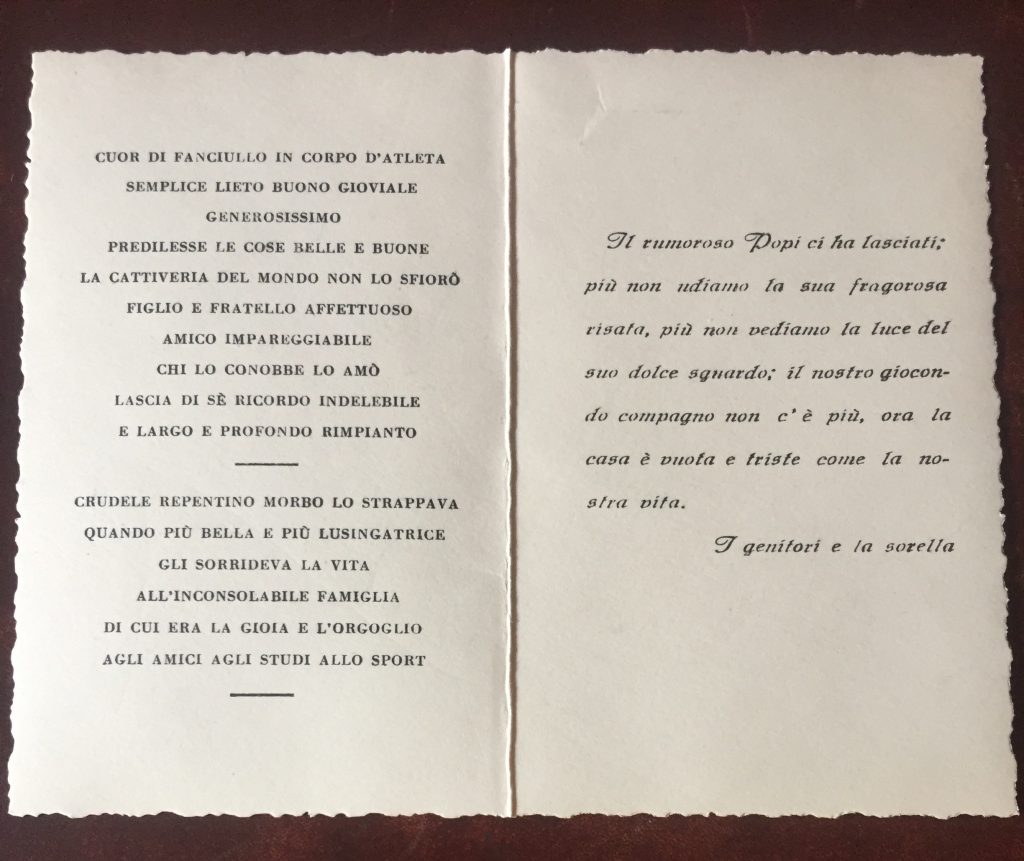

- Popi is described as ‘a child’s heart in a sportsmen body’ [inner part, left, 1st line]; a ‘mean and sudden disease’ that robbed the family, of ‘whom he was the joy and the pride’, the friends, the study and the sport of Popi.

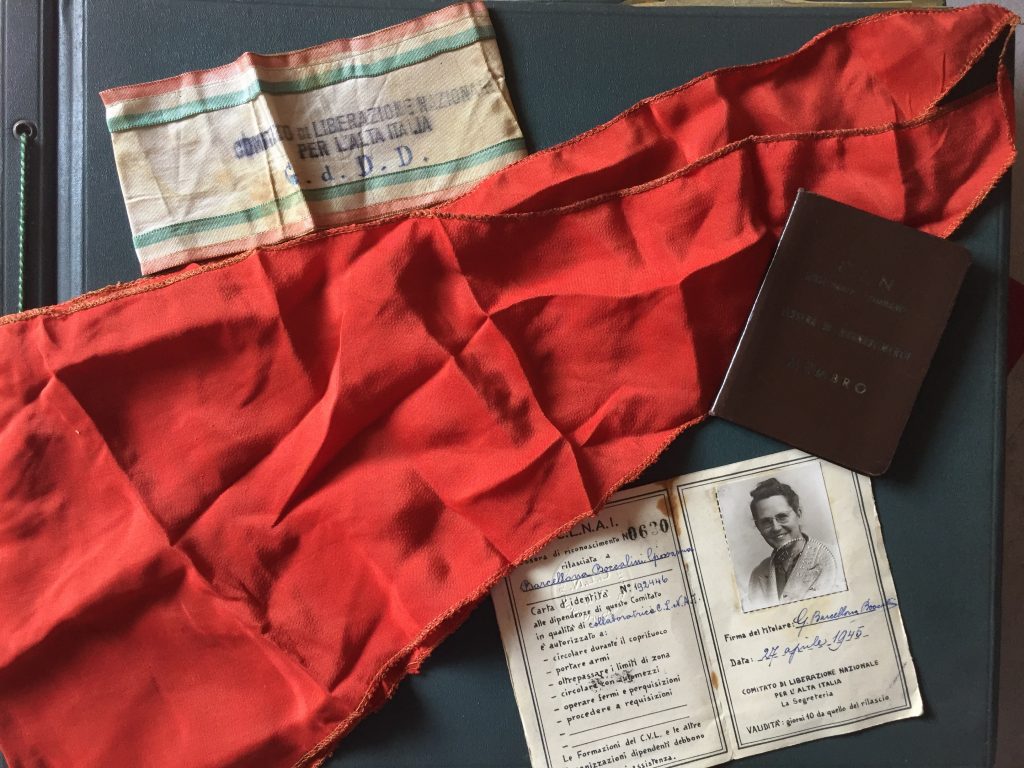

In the same summer that Giovanna lost her first-born son, Giovanna decided to join both the Communist Party and the Italian Resistance, being one of the founders of the Gruppi di Difesa della Donna, he also took charge of the GdD underground newspaper ‘Noi Donne’, and Giovanna hosted, in his house in via Francesco Reina, 15 people who were wanted by the Nazi-Fascist forces.

Giovanna’s documents as a member of CLNAI, the governing body of Italian resistance that worked as a provisional government in Northern Italy after the Liberation [April 1945]

Her red neckerchief and the white armband of Gruppi di Difesa della Donna.

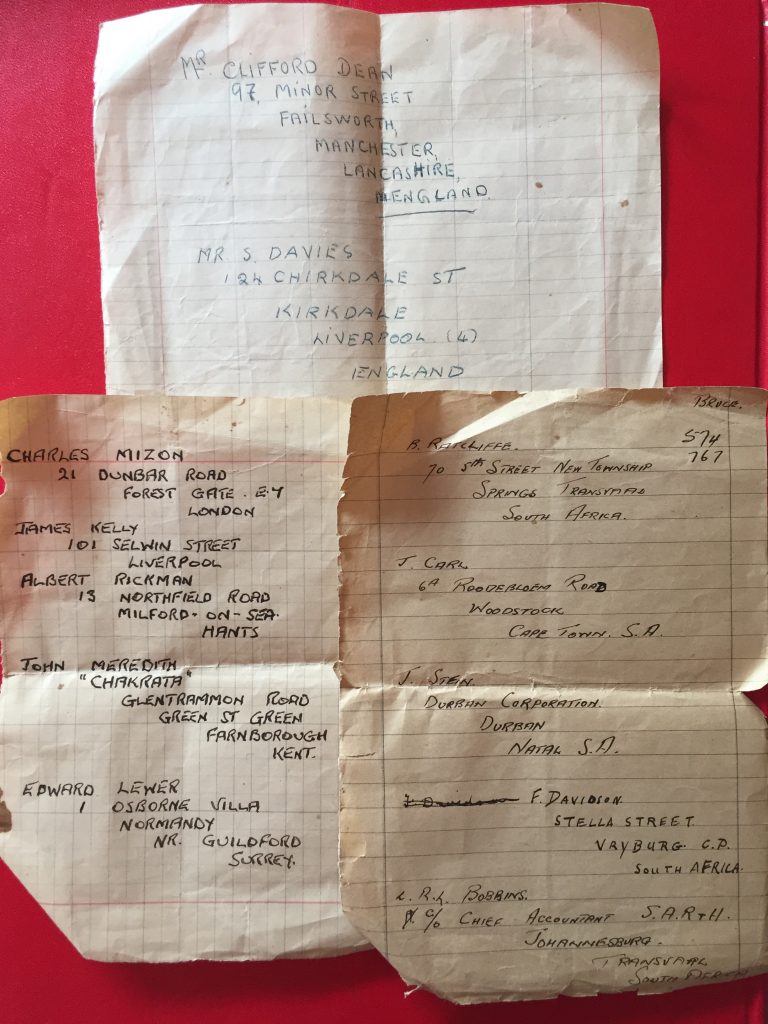

The 3 leaflets with the addresses of the 7 British and the 5 South African soldiers helped by Giovanna

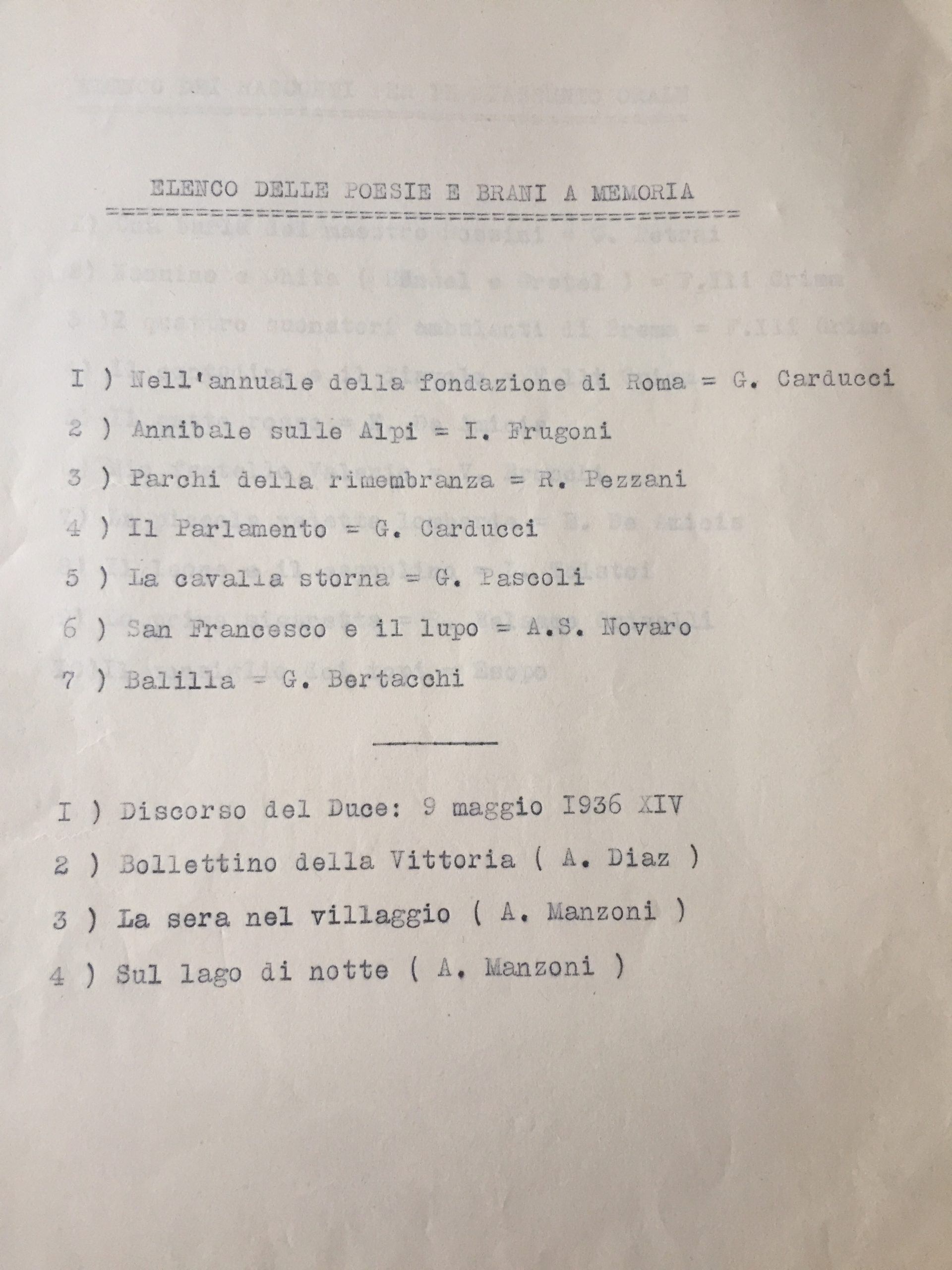

Coming back to the 1930s and we should remember that Giovanna had to raise Popi and Grazia during the Fascist regime, which controlled every aspect of sport in the country, including sporting activities in school, the PE teachers in Italian schools were recruited not from among the School Ministry, but by the Fascist youth movement, the ONB [Opera Nazionale Balilla] and from 1937 the GIL [Gioventù Italiana del Littorio]. Furthermore, beginning in the 1933/1934 school year, every student attending an elementary school in Milan had to be registered for the ONB by their parents, who, on the other hand were not forced to send their children to the ONB events. So Popi joined the ONB in 1933 and Grazia in 1935, when she was only 6.

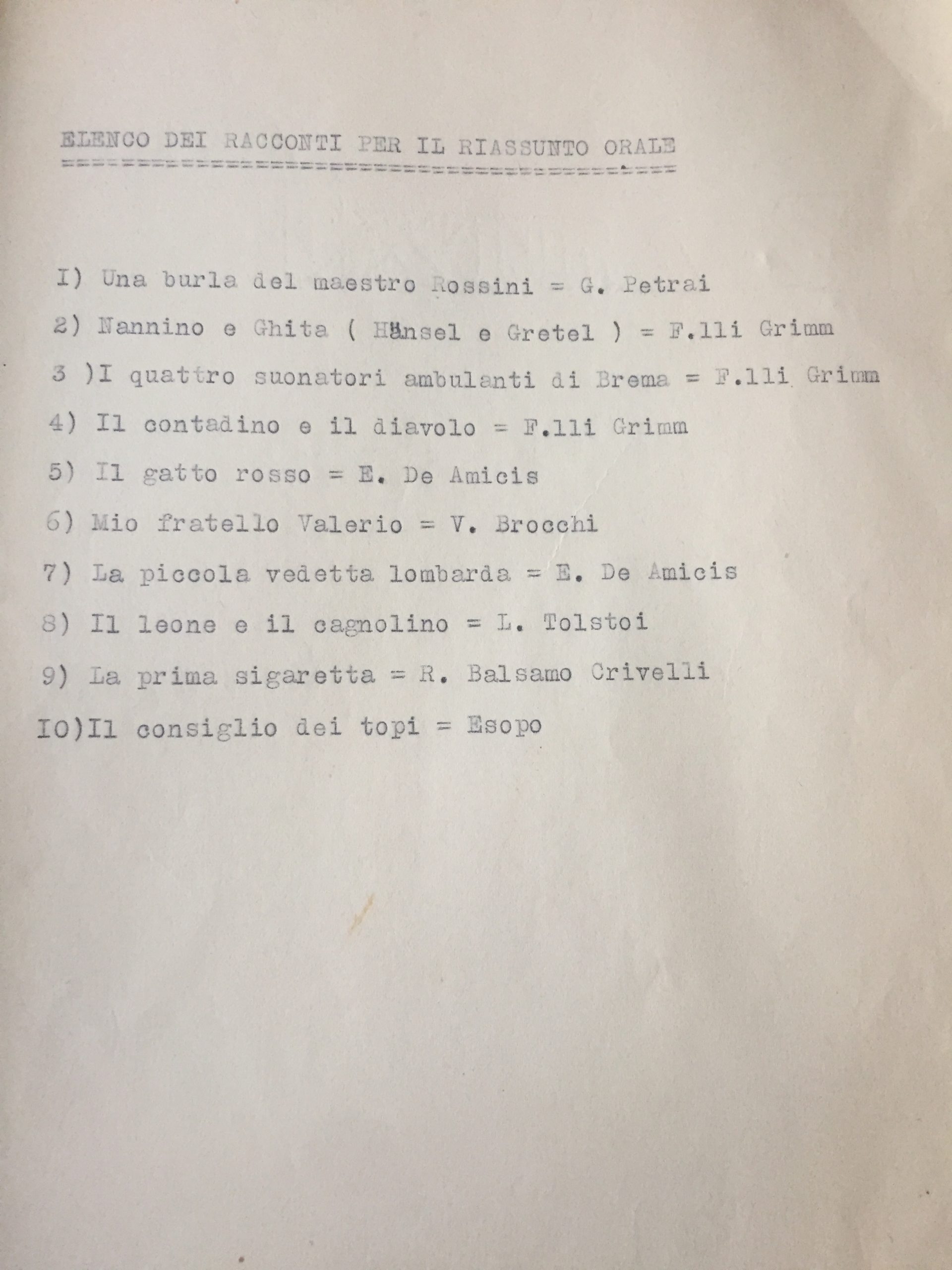

The complete list of 1936/1937 Italian ‘programma’ of Popi’s exam of admission to ‘scuola media’ [middle school, from 11 to 14 years]. These are all the poems that the 10 year-old Popi had to be able to recite by heart, and the sentences on which he had to complete an oral summary. Note that, among Italian literary classics such as Pascoli and Manzoni, and a lot of other nationalistic works, there is also Mussolini’s 1936 speech in which the Duce announced the complete conquest of Ethiopia and the consequent birth of the Italian Empire

The cover of 1938/1939 Grazia’s report card

Note the fascio littorio, and the GIL acronym

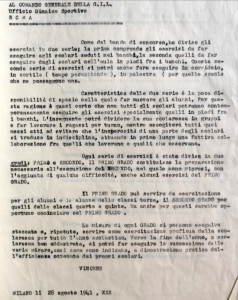

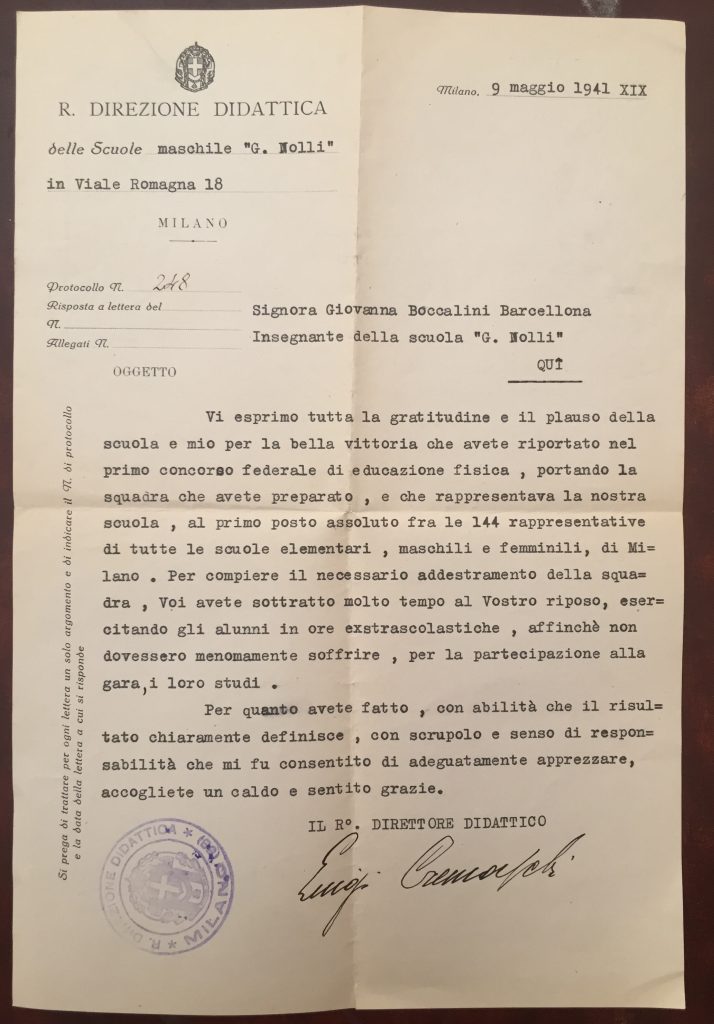

Despite these hard times, Giovanna didn’t give up, she tried to communicate her love of sports using the little power she had as a teacher in the viale Romagna Boys elementary school. Among her tasks, as well as some PE teaching hours, in 1940/1941 she decided that the pupils would compete at the 1st Federal Physical Education Championship. Giovanna’s team won 1st place out of the 144 teams from the Province of Milan. In a letter dated May 1941, the Headmaster Luigi Cremaschi praised Giovanna’s hard work after which she was able to prepare her pupils for the sporting event without taking time out of other subjects in the timetable.

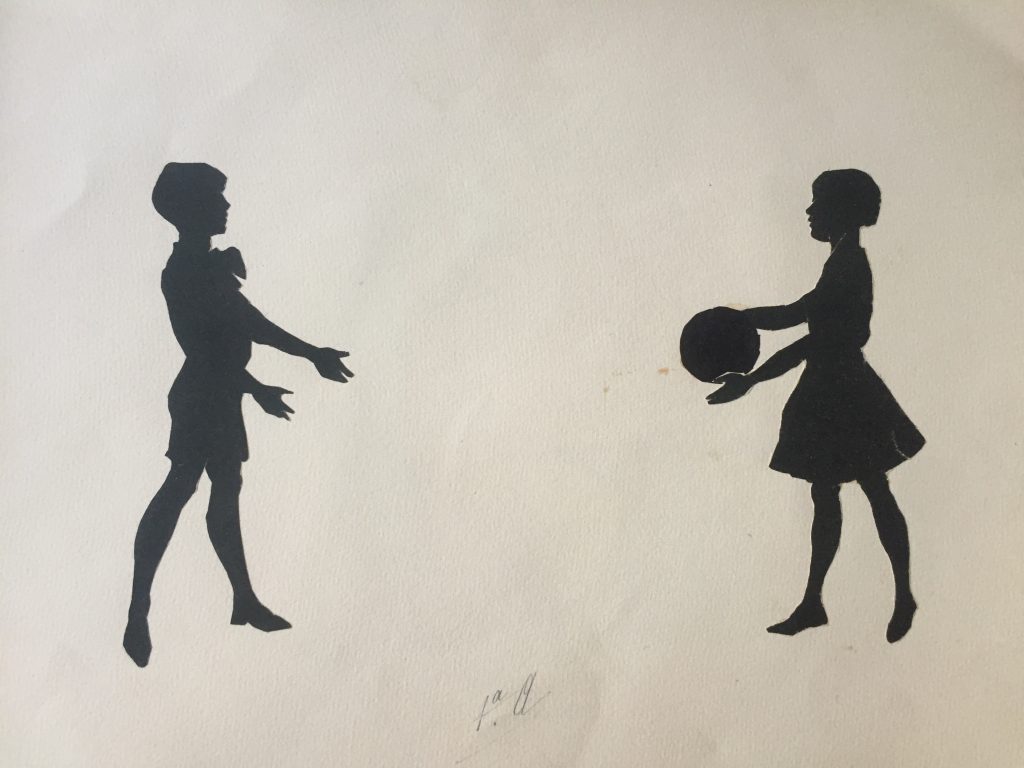

This image of a boy and a girl playing with a ball is taken from a collage album, which probably belonged to Popi, or maybe another one of Giovanna’s students

1941 Luigi Cremaschi’s letter to Giovanna

-

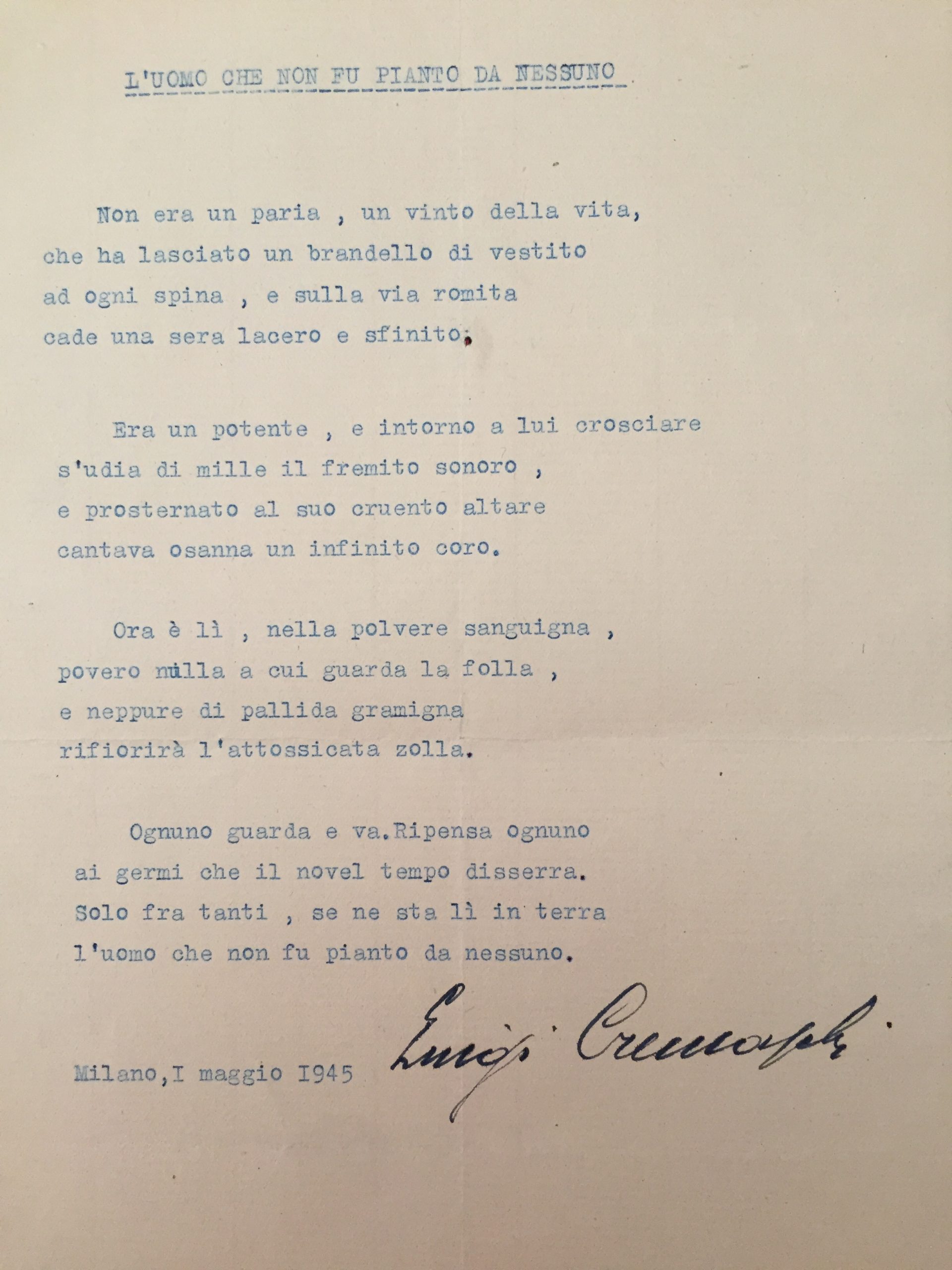

Despite his career during the Fascist Ventennio and his adherence to the National Fascist Party, we can argue that Cremaschi was quite a free-minded school manager

In late 1939 he was removed from Umberto di Savoia special school [Milan] because he was considered not loyal enough to Fascist ideology

In Giovanna’s archive this poem by him, written on 1st May 1945 can be found

It talks about the death of Mussolini, who had been killed near the Swiss border on 28th April 1945 by the Italian Resistance partisans and who later showed the Duce’s corpse to the Milanese people

In the poem Cremaschi describes Mussolini’s fall, from the cheering crowd to the final dust.

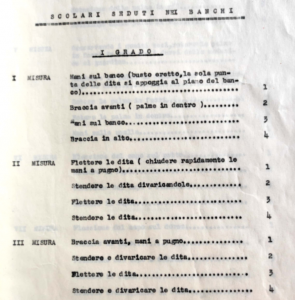

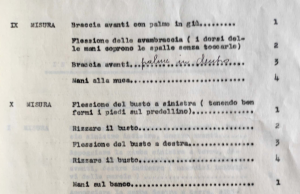

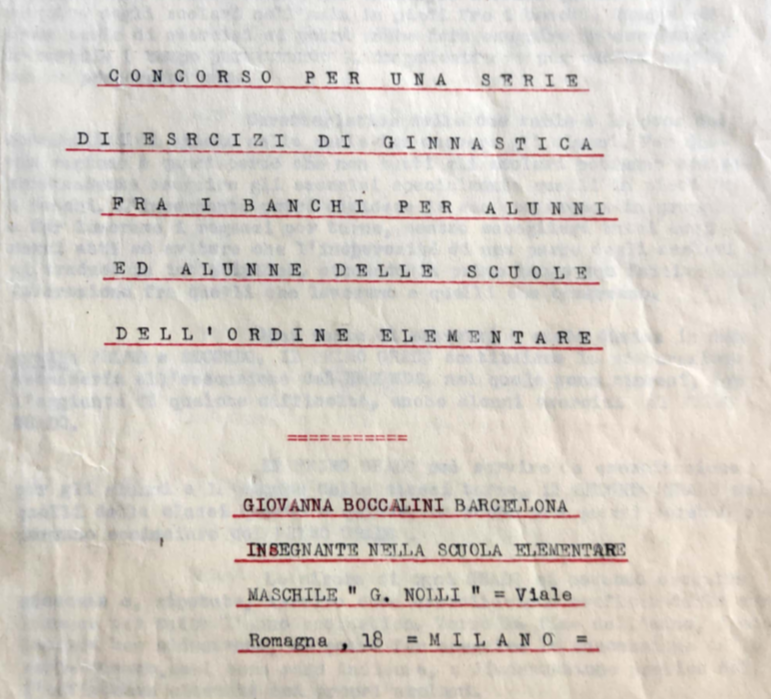

Some months later, in October 1941, Giovanna took part in a national GIL competition for elementary school students physical exercises, these exercises were carried out in a standard classroom and not in the school gym.

Up to now, it seems that Giuseppe had played only a passive role within the sporting couple, BUT World War 2 would change everything.

Giuseppe, the rower

First of all, it should be remembered that Giovanna’s husband was a big football fan of Ambrosiana-Inter, of course, as were all the Boccalini sisters.

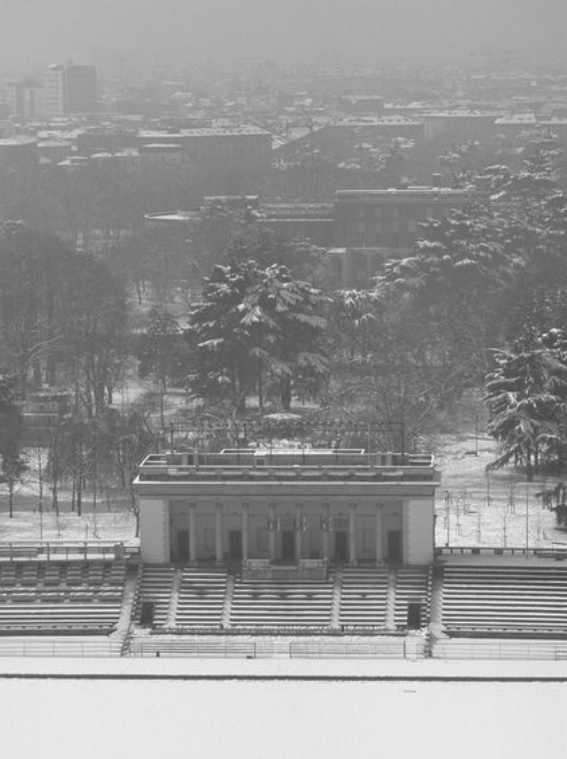

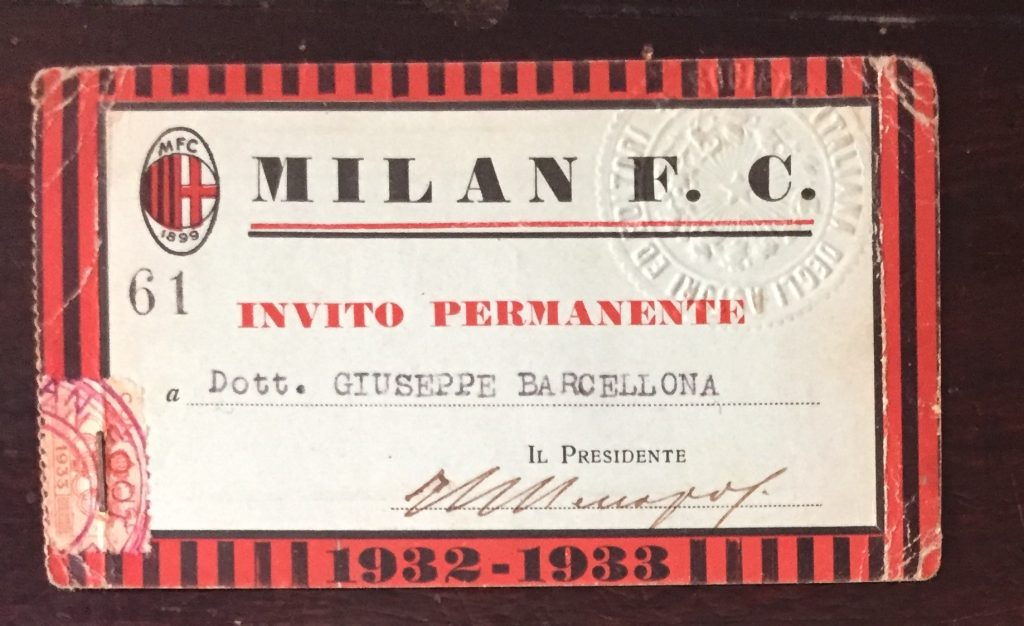

Giuseppe’s 1932/1933 Ambrosiana-Inter season ticket. He had access to the Pulvinare or the grandstand of Inter stadium

The Pulvinare, with Parco Sempione un the background [2005]

Source: https://bit.ly/2GbU4CX

AC Milan ‘invitation’ to Giuseppe

This seems to be just a complimentary ticket for the rossoneri matches

We don’t know if Ambrosiana-Inter fan Giuseppe ever used it!

It was kept hidden under the Inter season ticket, as if it was something to be ashamed of …

Then Giuseppe became the team manager of Ambrosiana Inter women’s basketball team, just for the away matches. As we already know [see http://bit.ly/2m9hfnb ] in the late 1930s and 1940s his sister-in-law Rosetta Boccalini was a player for this team.

A more detailed version of the picture published by Annuario della Gazzetta dello Sport 1940, p. 117

From left: Rosetta Boccalini [15] Anna Giacconi [8] Bruna Bertolini [4] Rosetta Gilieri, Pierina Borsani [7] Angela Vacchini [14] Laura Grassi [9] Neri Bertolini [5] Wanda Rizza [10] Olga Mauri [12]

Coach Umberto Fedeli and president Ferdinando Pozzani

Ambrosiana players having a lunch, probably at the house of one of the players’ mothers

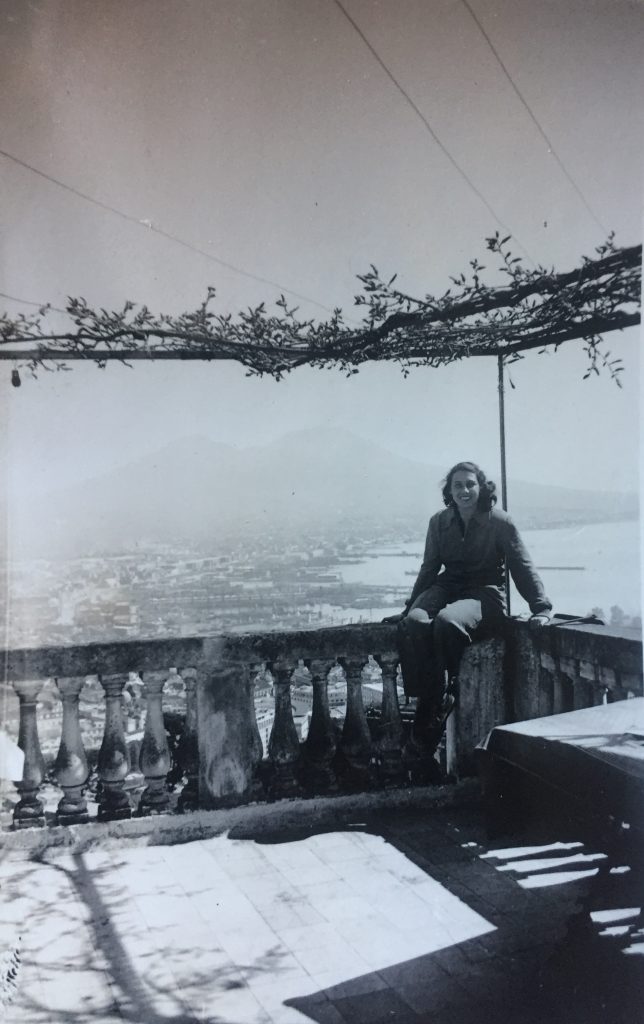

As Paolo Gilardi, Rosetta’s son, told me many times and her sister Marta writes, perhaps with a touch on envy in her memoir Ricordando, basketball was a big event for Rosetta and her teammates, especially away matches, for which they travelled all over Italy. In the 1940/1941 season Ambrosiana faced teams from Genua, Florence, Naples, Bologna, and Rome, all at a time when almost no Italian girl had the chance to travel without their family, and yet they did it!

- Ambrosiana players during a train trip

- Players on the promenade in Naples

Players in team kit

Standing, from left: Adriana Mengaldo; Maria Mengaldo; ?; Anna Giacconi; Olga Mauri [or Matilde Moraschi?]; Bruna Bertolini; Pierina Borsani.

Crouched: Wanda Rizza; Nerina Bertolini; Olga Mauri; Angela Vacchini

Ambrosiana players visiting Palazzo Ducale, in Venice

Rosetta is the 3rd standing; Giuseppe Barcellona and his wife Giovanna [without glasses!] are seated.

The elderly woman on the right may be the mother of a player

Players at the seaside restaurant

From the left: Olga Mauri [?]; Angela Vacchini; Nerina Bertolini; ?; Bruna Bertolini.

At the head of the table: ?.

On the right, from the bottom: Maria Mengaldo; Rosetta Boccalini; Giovanna Boccalini Barcellona; Matilde Moraschi; Giuseppe Barcellona

- Marta and Rosetta [dressed for basketball]

- From left:?; Rosetta Boccalini; Giuseppe Barcellona; Giovanna Boccalini Barcellona; Bruna Bertolini [?]; coach Umberto Fedeli; Angela Vacchini; Nerina Bertolin

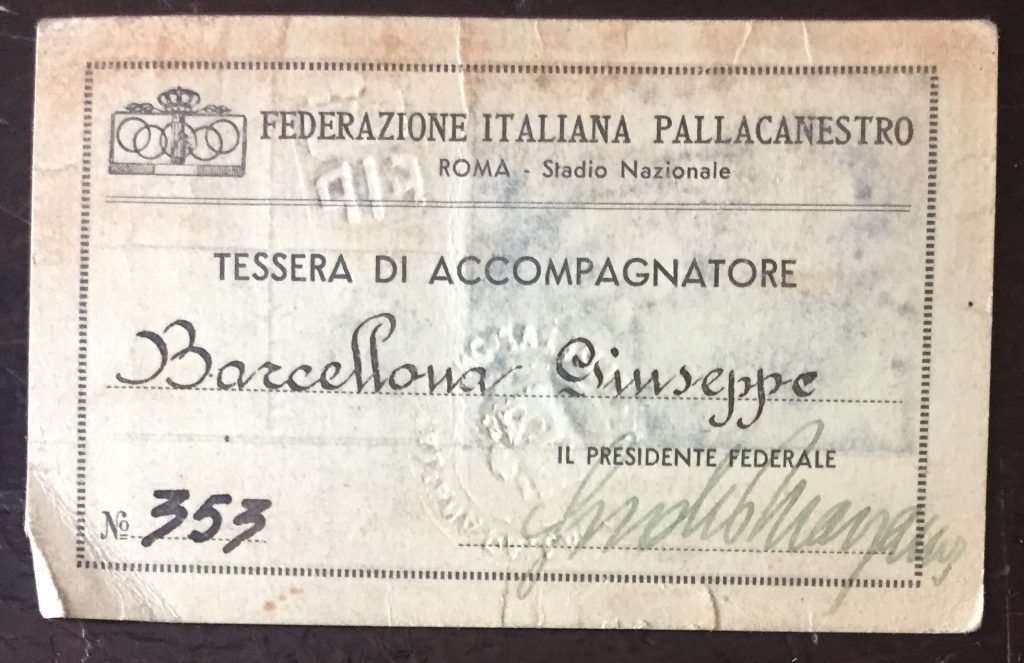

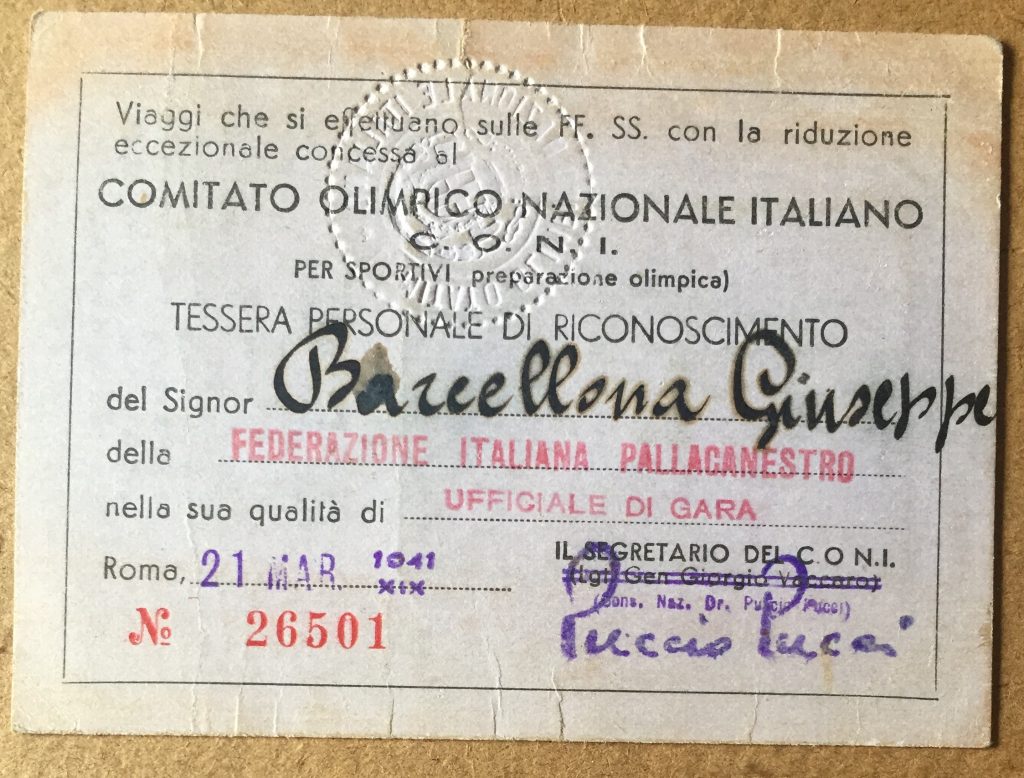

Unlike Giovanna, Giuseppe role was official, he was appointed as dirigente accompagnatore or ‘team manager’.

-

Standing: the coach; Bruna Bertolini [4] Matilde Moraschi [3] Rosetta Boccalini [15] Ferdinando Pozzani [President]

Maria Mengaldo [8]? [11] Giuseppe Barcellona

Crouched: Adriana Mengaldo [10] ? [14] Nerina Bertolini [5] Angela Vacchini [in suit] Olga Mauri [12] Rosetta Gilieri [6?]

-

Standing: coach Umberto Fedeli; ? [10] Nerina Bertolini [5] Angela Vacchini [9] Olga Mauri [12] Wanda Rizza [18] Giuseppe Barcellona

Crouched: Matilde Moraschi [3] Bruna Bertolini [4] ? [14] ?

- Coach Fedeli, Bruna Bertolini, Giuseppe

- Giuseppe Barcellona with 3 players on a coach

The team having a coffee at a bar.

Giuseppe is the first from the left; Angela Vacchini is at the head of the table

Right, from the bottom the 1st is Olga Mauri and 3rd Nerina Bertolin

Giuseppe and a player, after lunch in a restaurant

Giuseppe’s two ID cards suggest that he officially began his sporting management experience as late as Spring 1941, which is very interesting for two reasons. First at all, after being sent to serve at the Lybian front against the Allies for some months, he ‘washed’ his political anti-Fascist past and then, in 1941 when a lot of adult men had already been sent to the front, from those few who remained in Milan someone had to take care of that female basketball team. Giuseppe was perfect since he was the nearest relative of Rosetta, who had been orphaned after her father Francesco died in the late 1920s, and she was not yet married.

Giuseppe’s FIP [Italian Basktball Association] card, issued on 16th March 1941

- Giuseppe’s CONI [National Italian Olympic Committee] personal card, dated 21th March 1941. This card was useful as it could be used to get discounts on train tickets.

Giuseppe, the team manager, 1st from the right, standing

This photo was probably taken during a season in which Rosetta was no longer playing in the team: her usual 15 shirt is being worn by another player

On 16 March 1941, Ambrosiana travelled to Naples, in order to play against GUF Napoli. Since Rosetta is not mentioned in the La Gazzetta dello Sport article about the match [18/03/1941, p. 6], we could assume that she stayed in Milan. A lot of images from this trip have been preserved and it maybe had been Giuseppe’s wish to show them to his sister-in-law in Milan?

-

The Ambrosiana team in Naples: as shown by the signs on the left

The Milanese players won 21 – 12

According to La Gazzetta dello Sport, the team was made up of Bruna Bertolini, Nerina Bertolini [8 points], Moraschi, Rusconi, Olga Mauri [3], Angela Vacchini, Mondani [2], Maria Pia Re [8]

-

The team under a pergola

Standing: Moraschi; ?; ?; Nerina Bertolini; Giuseppe Barcellona; ?; ?

Seatiing on chair: ?.

Seated: Angela Vacchini; ?; ?

- Nerina Bertolini under the pergola

-

Another basketball player

Note the Vesuvio volcano in the background

The team on the promenade

We need to remember that a lot of photos were taken by Rosetta herself and we can safely assume that among the players Nerina and Bruna Bertolini were ‘best friends’ with Barcellona-Boccalini family.

- Nerina Bertolini and Giuseppe, during a train trip

- Giuseppe, Bruna Bertolini and coach Umberto Fedeli

-

Two Ambrosiana basketball players in official uniform

Matilde Moraschi [?] and Bruna Bertolini.

-

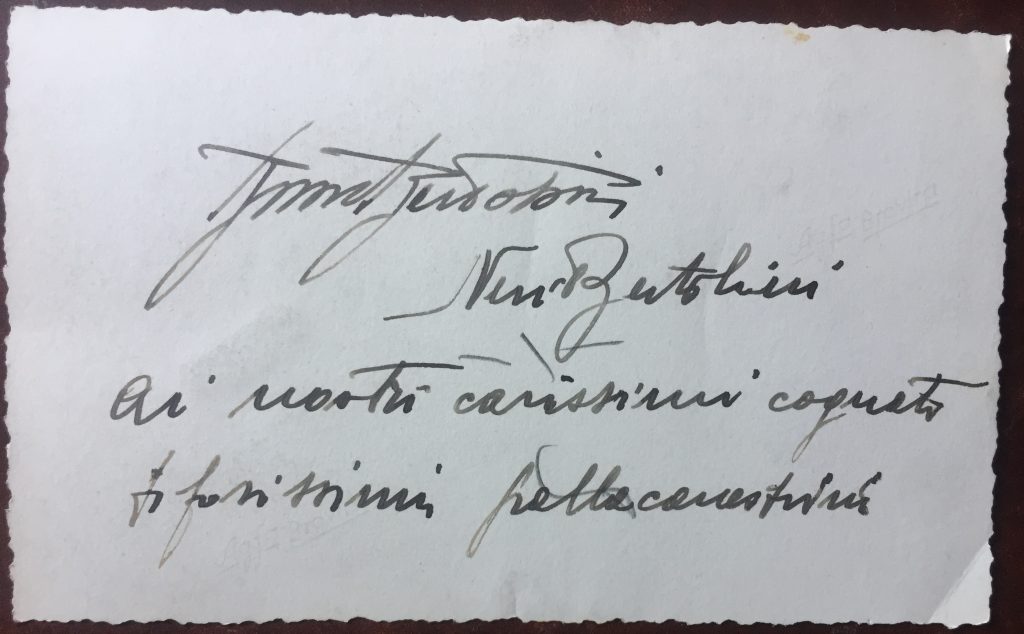

Bruna and Nerina Bertolini in the National team shirt

Unlike Rosetta, they were both called for the 1938 European women’s championship, won by Italy

On the back of the previous photo, the Bertolini sisters hailed to ‘our dearest “cognati”, who are hard basketball fans’

The word cognati could refer either to in-laws Giovanna and Giuseppe [who were Rosetta’s “cognati”], or to Giuseppe and another brother-in-law (Bruna’s or Nerina’s) who helped the team

These two images taken in 1939, perhaps suggest that Nerina [1st from the left in the 2nd photo] and another girl spent their holidays with Barcellona-Boccalini family

In 1941 at the same time as Giuseppe was spending his free time with Rosetta’s team, Giovanna was following the early career of her ice-skating daughter Grazia.

- Grazia and Giovanna in a boat

- A very young Grazia practicing tennis, probably during her holidays time at the sea [note her tan]

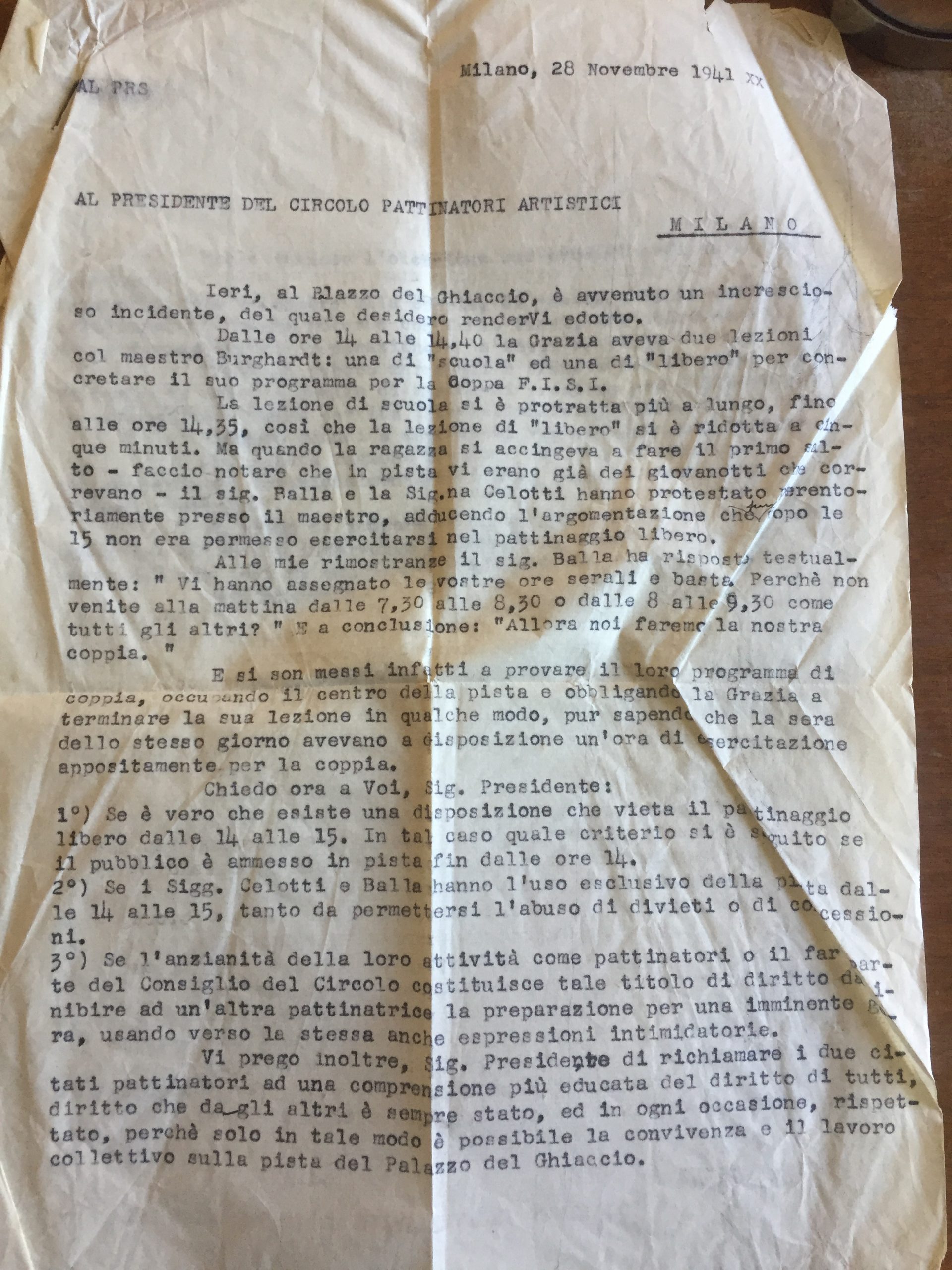

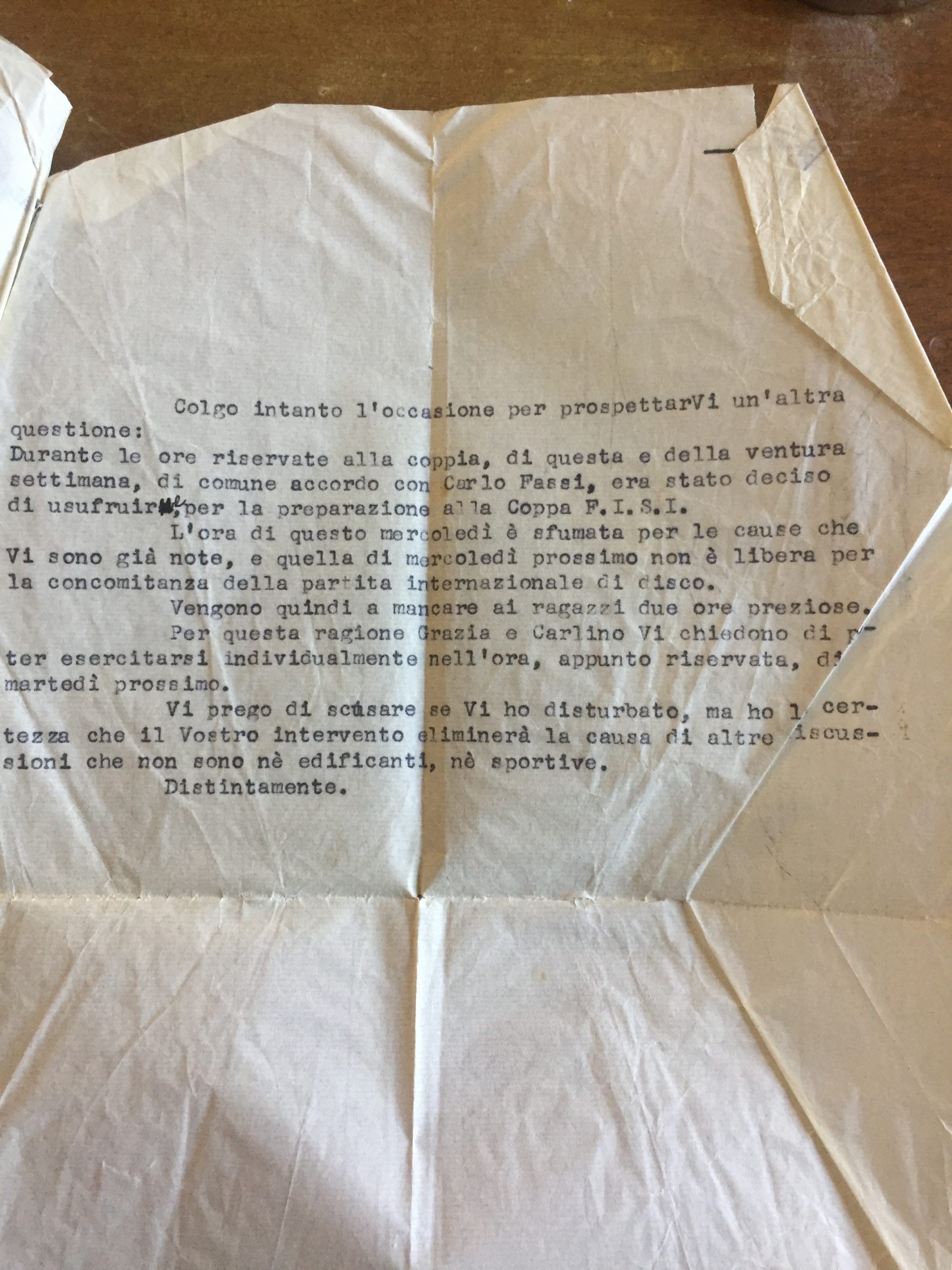

As Giovanna’s herself recalled in a 1978 interview, her spiritual guide Ettore Archinti had suggested that the ‘puny’ Grazia should practice ice skating at the Palazzo del Ghiaccio, which was very close to the Barcellona-Boccalini house. In November 1941 Giovanna wrote a letter to Remo Vigorelli who was not only the president of the ice skating society but also the father of Ciacia, Grazia’s future Olympic partner, complaining that the last lesson coach Burghardt gave to Grazia and her partner Carlo Fassi [see http://bit.ly/33kXjz4 ] was interrupted by a couple of older skaters. They probably didn’t know what kind of mother Giovanna was!

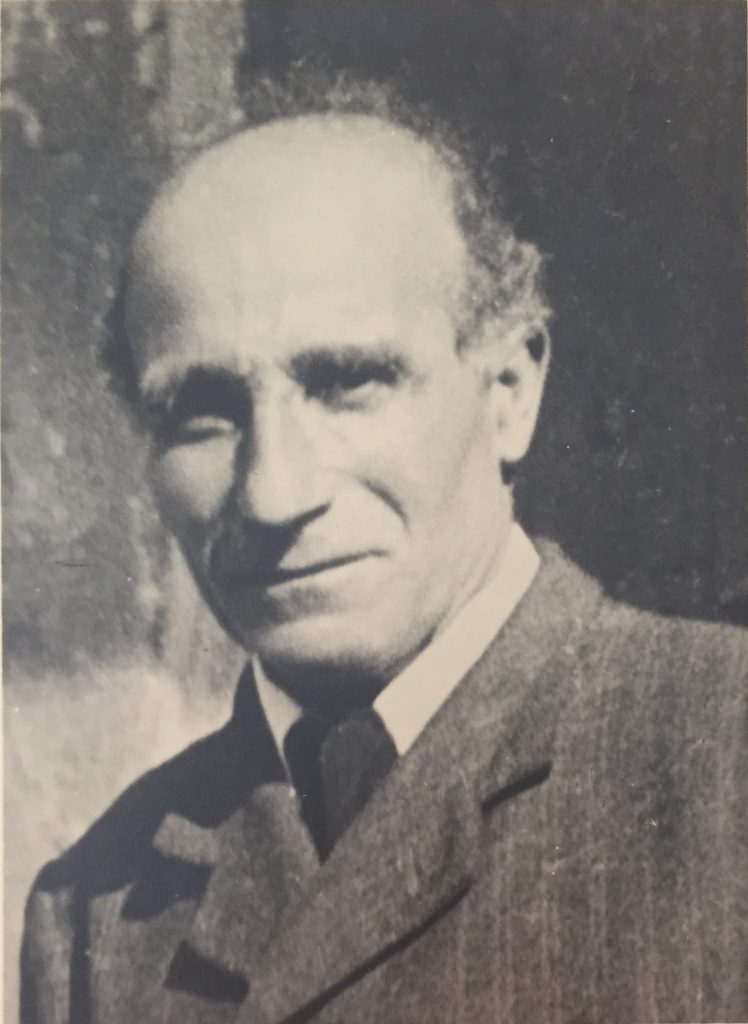

An older Ettore Archinti

The letter Giovanna wrote in 1941 to defend Grazia and Carlo’s right to have their ice-skating lesson.

It seems that both during and after World War 2 Giovanna’s interest in sports began to wane, her long political career, first in the Italian Communist Party [PCI] and in the left-wing union, then at the INPS [the main entity of the Italian public retirement system], left her with very little free time.

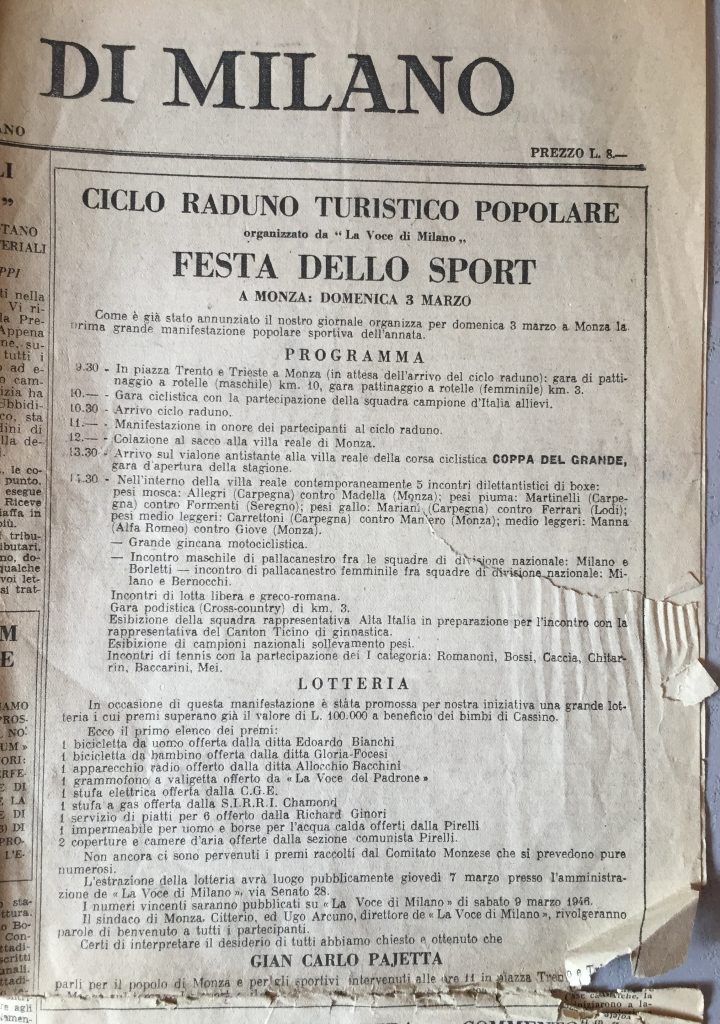

In this clipping held in Giovanna’s archive and taken from left-wing newspaper ‘La Voce di Milano’ [2 March 1946, p. 1] announces the upcoming ‘Ciclo Raduno Turistico Popolare’, a sporting event to be held in Monza the following day. Ambrosiana female basketball team [in which Rosetta was still playing] would be playing a friendly match

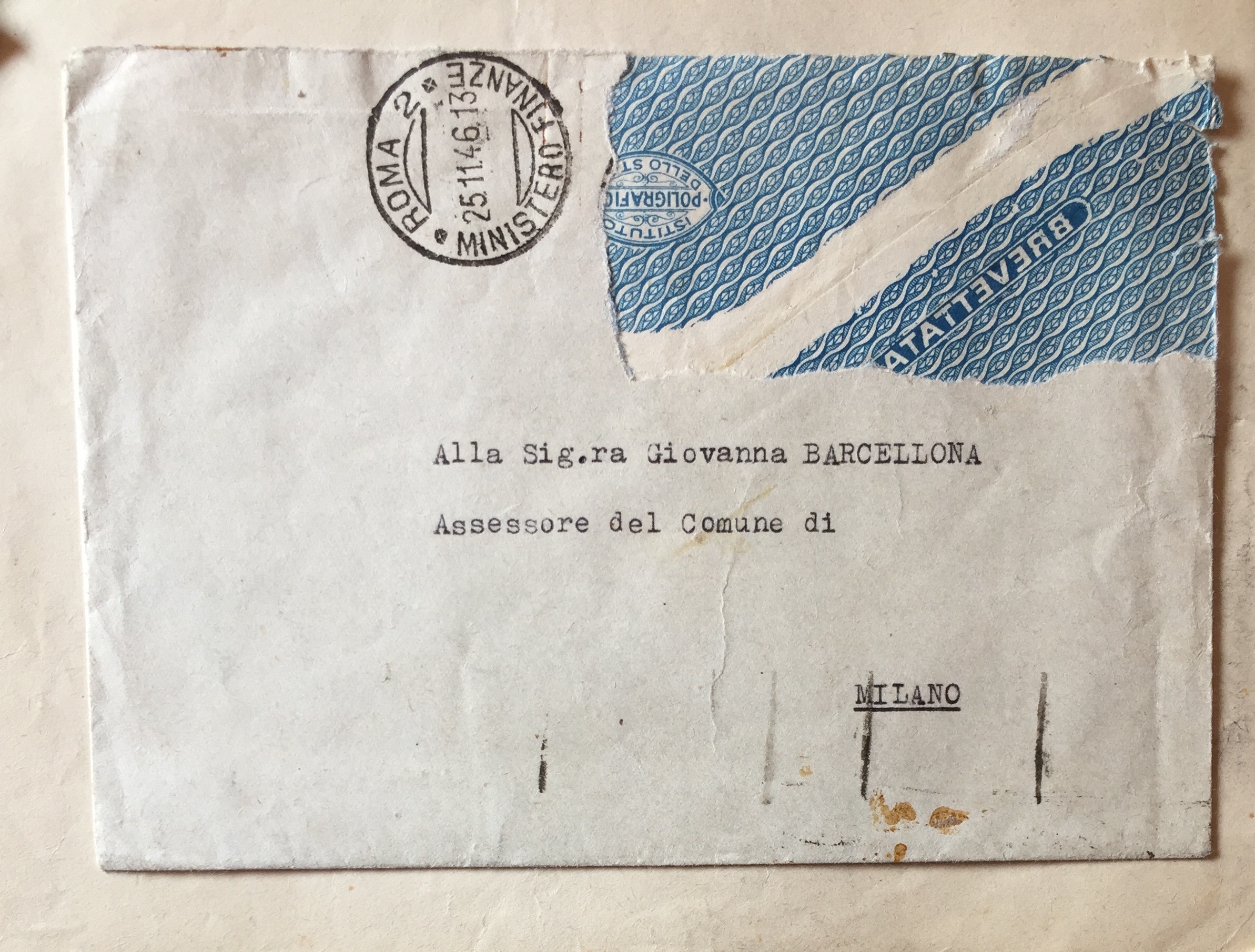

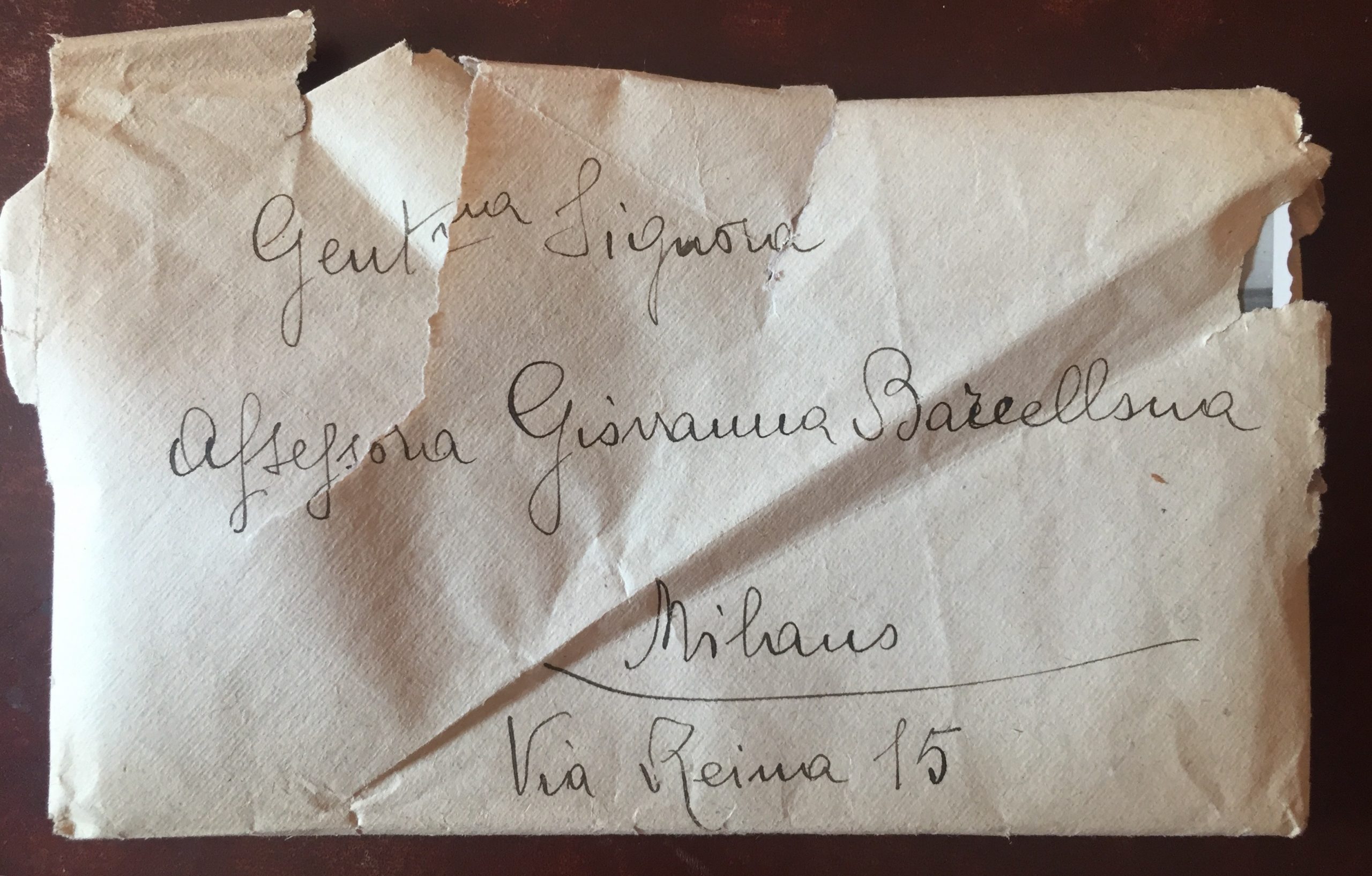

Giovanna was appointed ‘Assessore all’Assistenza’, Councilor for Social Services’ in the first City Council of Milan after the Liberation. At that time, because of historical reasons [women didn’t hold any political mandate at that time] the grammatical masculine form ‘Assessore’ was used event to refer to a female politician. It was only during the last years that a civil campaign asking for the use of the female form ‘assessora’ emerged. In the second image, a young female educator [Remigia Zorzini Lumachi] asking Giovanna for a job uses the form ‘assessora’. Since we don’t know anything about Remigia, we cannot be sure if she wanted to use this feminist form, or if she uses an analogical and more popular form to address a female politician. Nevertheless, although this form doesn’t come into common use in Italian until the late 1940s, it’s still interesting, because it speaks to us about a socio-linguistic need, a need that Italian speakers are now facing.

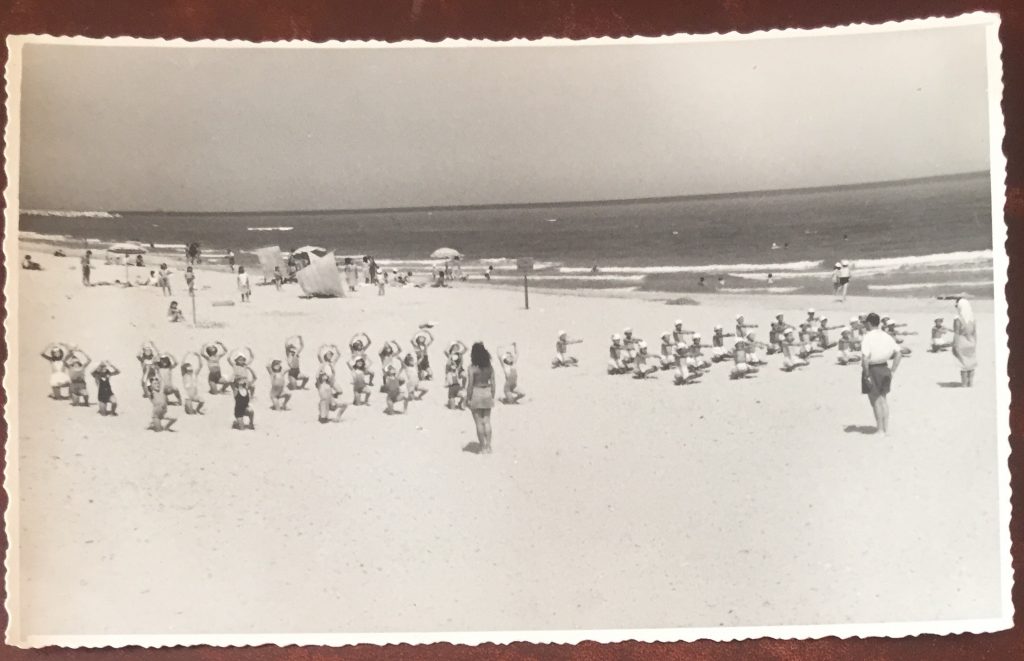

One of her tasks was the managing of the City youth camps, such this Colonia Perticari, located in Pesaro

Although these collective exercises for young boys and girls look very similar to those of the Fascist regime.

… there was a new interest in developing children’s artistic sensibility, such in these dances performed by little girls

Note the new Republican flag in the background.

In late 1951, Giovanna travelled to the URSS with a group of Italian Communist women: hosted by the PCUS, they visited St. Petersburg and Moscow

In the first city, the Italian women had the opportunity to visit the sports arena Micheal Manage [Russian: Михайловский манеж], where some female athletes were training.

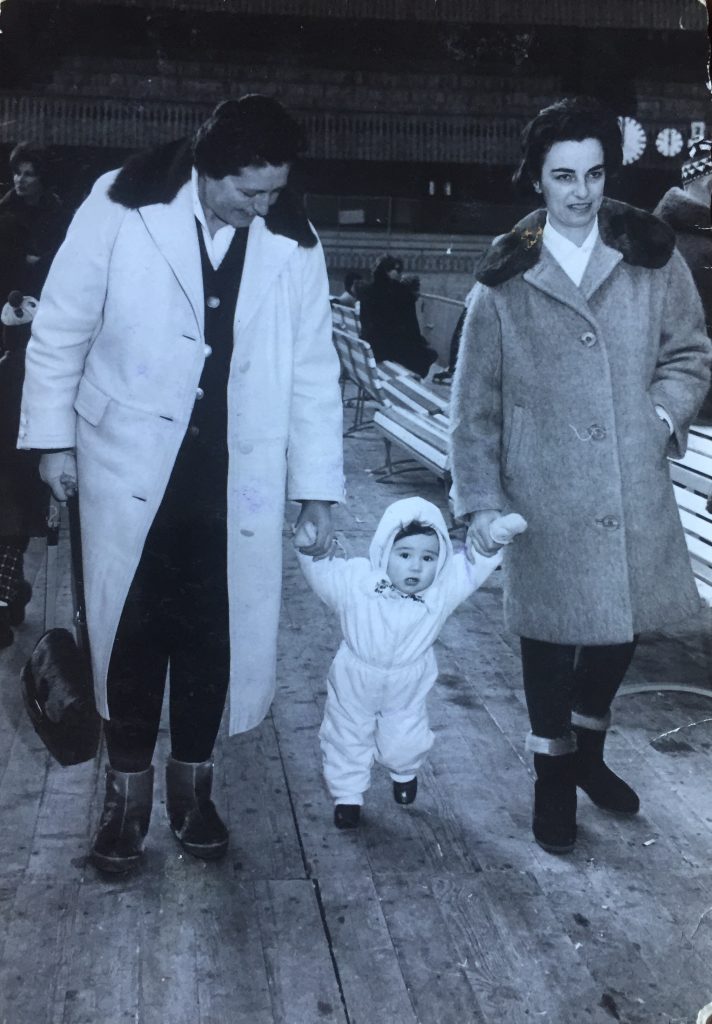

Giovanna, Cristina [Grazia’s first daughter, b. 1962] and Grazia at an ice rink

Giovanna walking in the snow.

-

Giovanna [in Superga shoes!], Grazia and a dog in their house in the mountains, in Casteldarne/ Ehrenburg

Chienes/Kiens, Südtirol

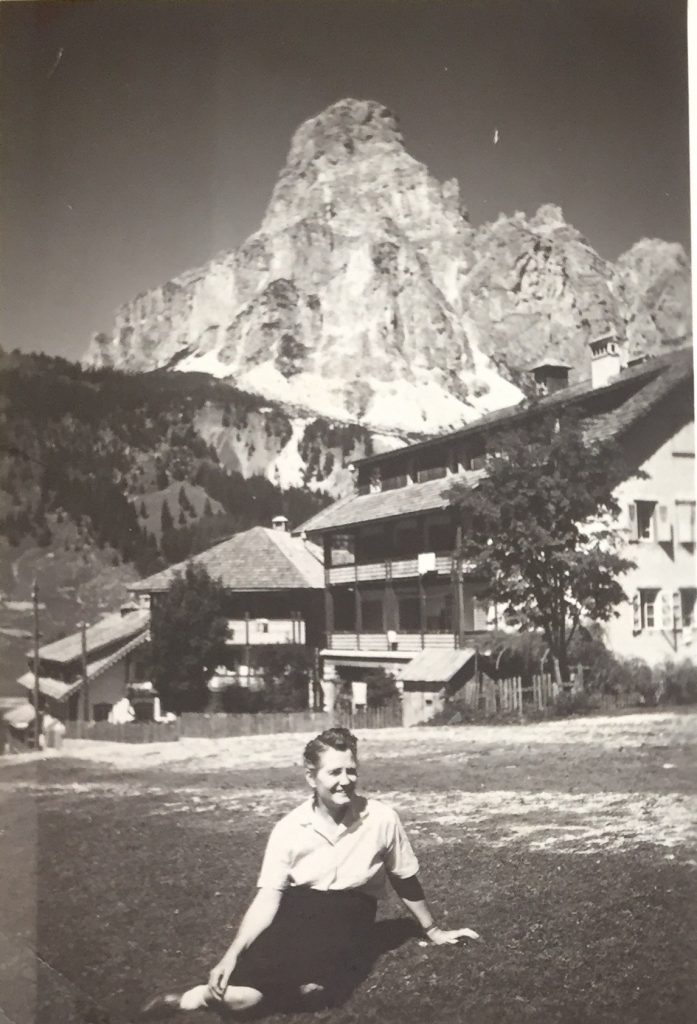

- Giovanna in sitting in front of the mountains

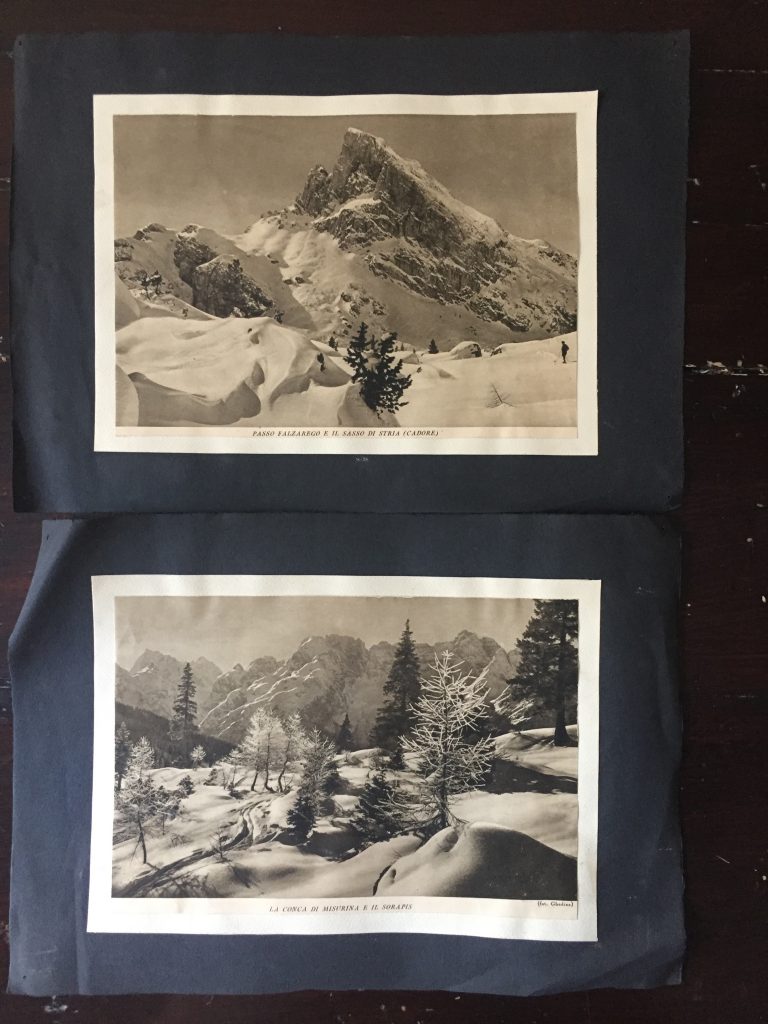

- These old prints depicting mountains were probably framed, and put on the wall of Giovanna’s house

-

This old ‘l’Unità’ [an Italian Communist newspaper]

Still folded in on an article about a victory of Inter on FC Bologna

[11 January 1982, p. 11]

Proof of the never-ending interest of Giovanna for her beloved ‘neroazzurri’

An older Giovanna sitting in her beloved Alps

Article © Marco Giani

To read Part 8 – Click HERE

For more images of Boccalini sisters, see:

https://sorelleboccalini.wordpress.com

![“And then we were Boycotted”<br>New Discoveries about the Birth of Women’s Football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 7](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Marco-Part-7-Boycotted.jpg)