All images are taken from:

Milano, Archivio di Stato di Milano, Prefettura di Milano, Gabinetto, Carteggio fino al 1937: serie I

All images are published with the permission by Ministero dei Beni e le Attività Culturali.

Any reproduction of images is strictly forbidden.

As seen in a previous Playing Pasts article (see https://bit.ly/39mZbdN ), the Milan Archivio di Stato could be considered a wealth of information regarding Sports History in Milan: the Prefettura papers, in particular, contain a lot of hidden stories about how sportsmen and sportswomen, clubs and sports federations interfaced with the Governmen, represented by the local Prefetto.

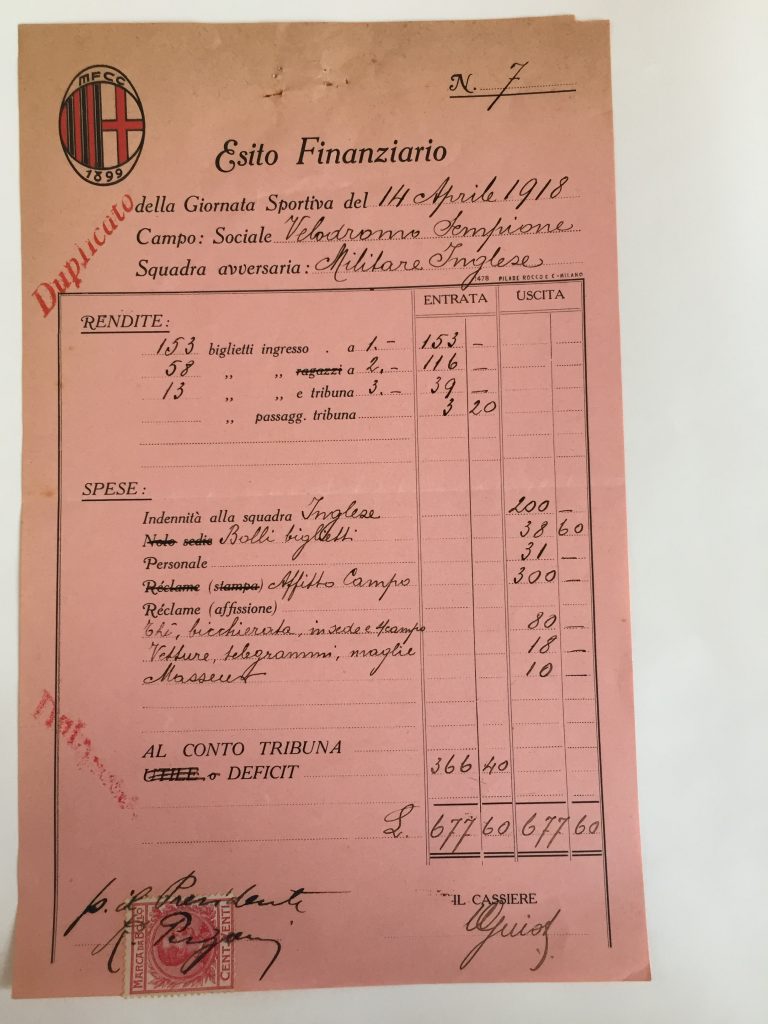

Let’s start with some numbers: economics, as we all know, is a primary element of modern sports. The Archivio di Stato papers includes a receipt from the match played on 14 April 1918 at the Velodromo Sempione between AC Milan and a British Army team from Arquata Scrivia (a small mountain town between Milan and Genua), who won 4 to 1. The star of the match was Percy Walsingham, a well-known British soldier and former footballer (Millwall, Clapton Orient and Chelmsford FC) who came to Italy in 1912, playing for Genoa CFC, winning the Italian scudetto in 1915.

Allied troops and Italian civilians watching a football match organised by the British 7th Division in a small Italian country town

Source: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205268079

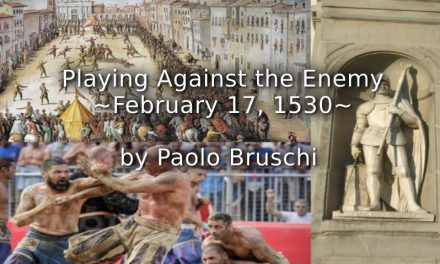

In this 1914 Genoa CFC Percy Walsingham (1st from the right) is wearing an English flag on his shirt

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Percy_Walsingham

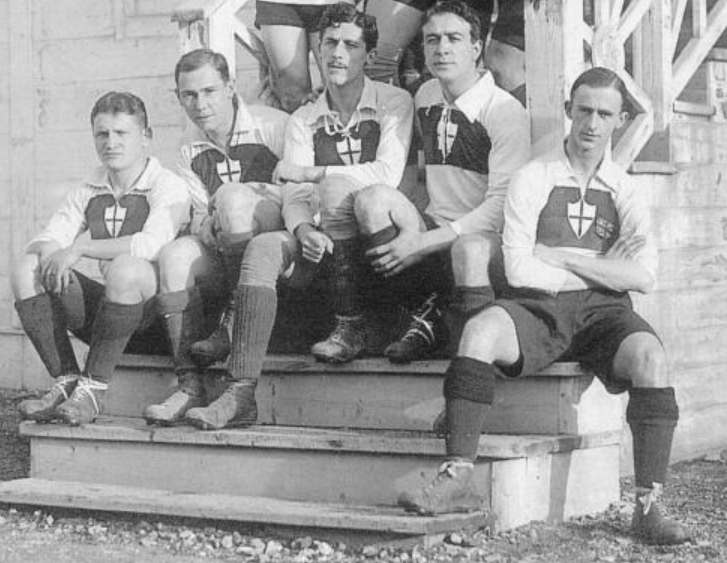

The 1913 project for Velodromo Sempione: it was going to be built one year later

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Velodromo_Sempione

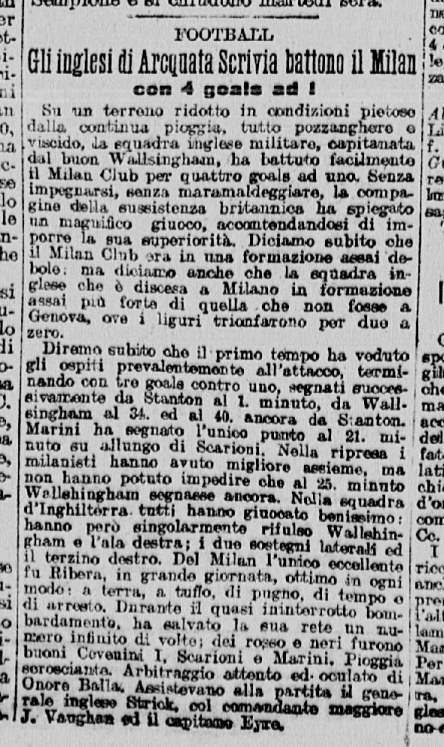

The Gazzetta dello Sport journalist writes, seen in the image below, that the pitch was in poor conditions because of the rainy weather. The British Army team, from Arquata Scrivia barracks, played a wonderful game, without ‘raging’ on the Rossoneri team, which was lacking a lot of players. The first half finished 3 to 1: the scorers were Stanton (1′), Marini (21′), Walsingham (34′), and Stanton (40′) again Walsingham scored the last goal, during the second half (34′) The journalist praised the English players and only goalkeeper Ribera among AC Milan players, who succeeded in saving the Rossoneri goal several times from the ‘relentless (British) bombing’

Source: La Gazzetta dello Sport, 15/04/1918, p. 2.

Officers and soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps at the Mechanical Transport Base Depot in Arquata Scrivia

Source: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205267645

Interior of repair shop at the Mechanical Transport Base Depot in Arquata

Source: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205267646

224 people paid to watch the match (mostly sitting in the cheaper seats); AC Milan gave 200 Italian lire to the British team, 300 lire to Velodromo Sempione for the cost of renting the stadium and 10 lire to the masseur. Since, apparently, 80 lire were spent for thé ‘tea’ and bicchierata (meaning – glass or drink) both at the headquarters and on the pitch, perhaps implies that something than tea was drunk by both players and management.

Please note that on the beautiful AC Milan logo you can still read MFCC: at that time, the official club name was still the original one, ‘Milan Football & Cricket Club’

Source: f. 1116.

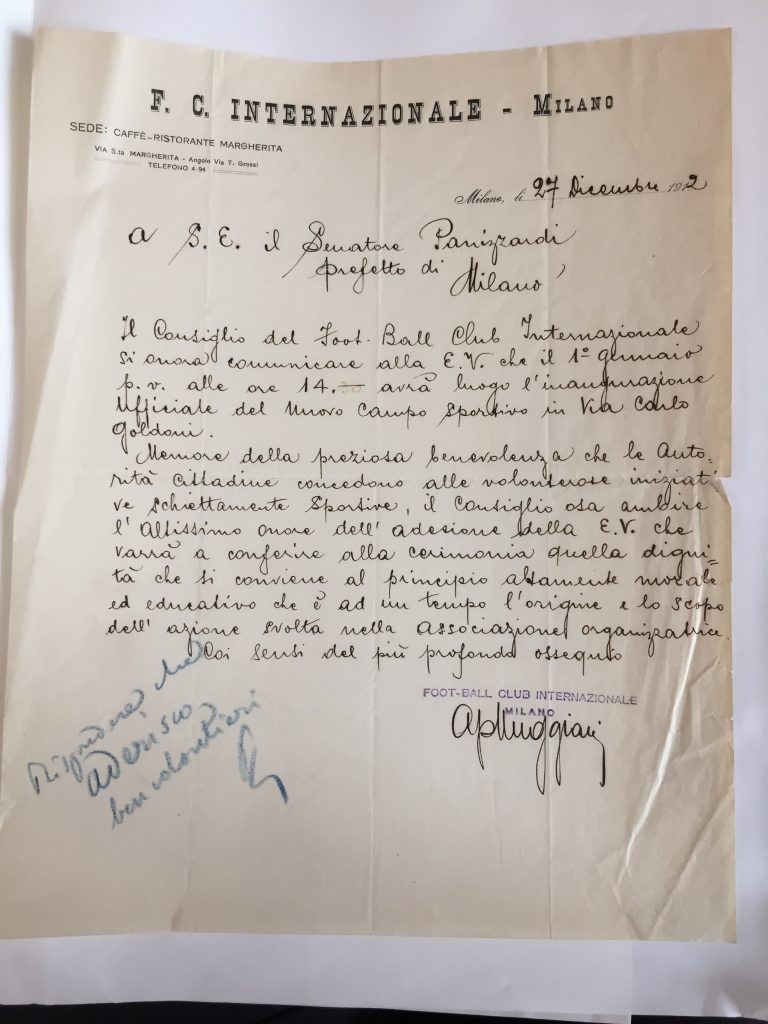

Let’s move on to a second issue. Sports need somewhere for participants to practice: the Milan Prefetto was welcomed at any stadium inauguration, such as on 1 January 1913, when FC Inter moved to their new football field in via Goldoni, a sports facility where in 1930, during a Serie A match against Genoa, the wooden and metal tube frame of the stands collapsed, resulting in 167 people being wounded. After this incident, FC Inter moved to the Arena Civica, where Meazza would become the favourite of the Nerazzurri crowd.

The 1913 letter of invitation

Source: f. 1116.

Via Goldoni football field: please note the black-and-blue FOOTBALL CLUB INTERNAZIONALE sign on the wall

Source: http://contropiede.ilgiornale.it/zizi-cevenini-il-primo-fuoriclasse-dalla-bocca-larga/

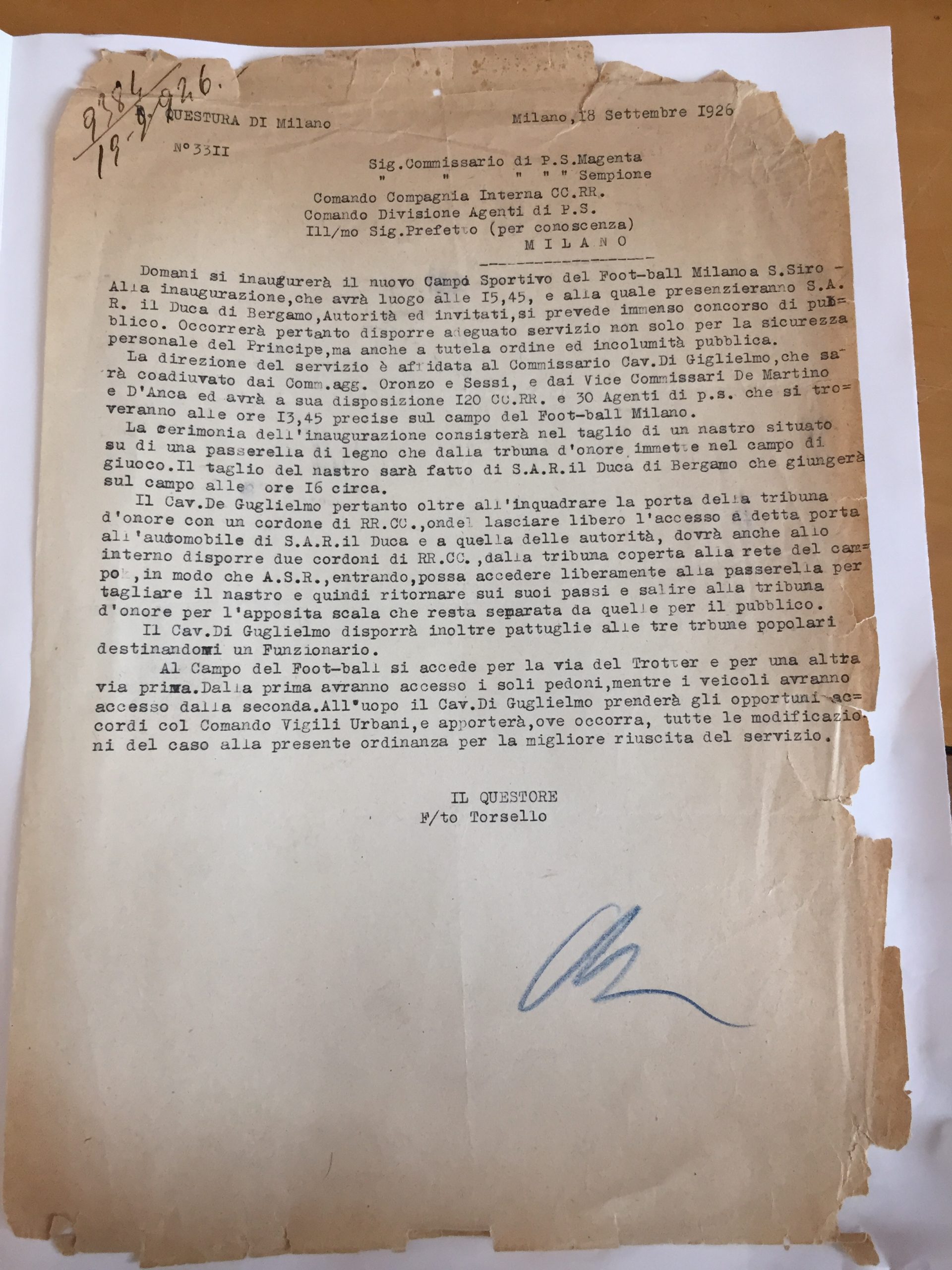

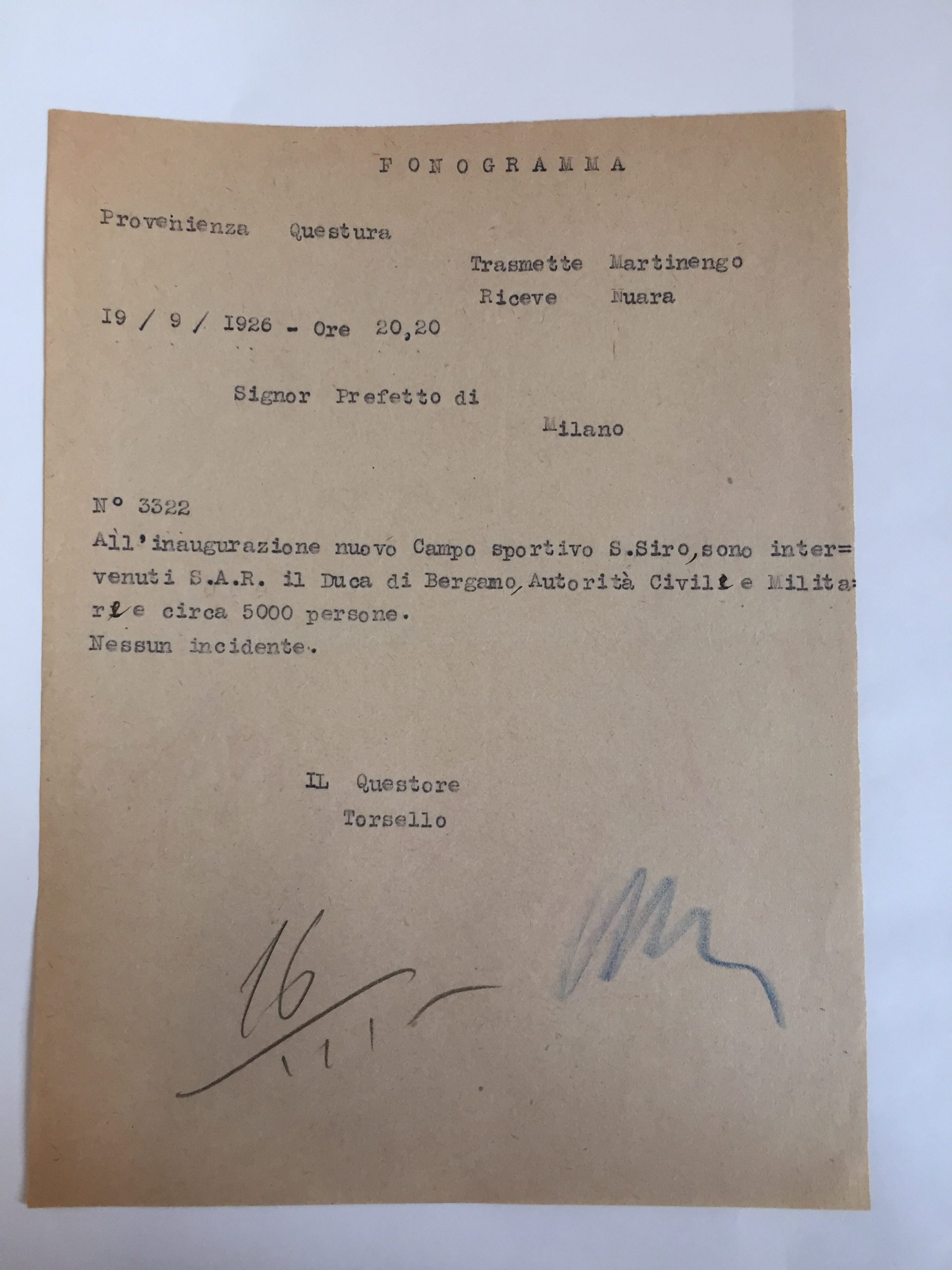

In mid-December 1926, AC Milan moved to the new stadium of San Siro: on 18 December Questore ‘Police Commissioner’ Torsello reported on how His Majesty the Duca di Bergamo (Prince Adalberto of Savoy, 1898-1982) performed the cutting the ribbon at the opening of the stadium, referring to the Duke’s security, Torsello describes the location of the official gallery, and the two stadium entrances, and how both needed to be checked by his bodyguards to ensure his safety. In the second paper (a transcription of a phonogram recording), Torsello says that everything went perfectly, the Duke was safe and he cut the ribbon in front of an audience of 5000.

- The situation as described by Torsello the day before the match Source: f. 1116.

- The phonogram Torsello sent at the end of the day Source: f. 1116.

San Siro stadium in 1935

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1198350818879123457

Guerin Sportivo, based in Turin, was one of the most important sports weekly papers

The title says: ‘AC Milan has inaugurated the biggest stadium ever!’

Source: Guerin Sportivo, 22/09/1926, p. 2

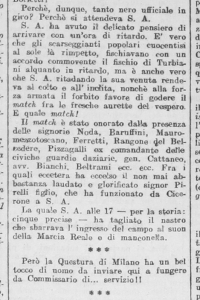

In the article, the Guerin Sportivo journalist whose nickname was ‘Coppet’ comments ironically that His Majesty’s ‘kind gesture of reaching the stadium one hour late’, thus allowing the audience to enjoy the evening breeze rather than the burning afternoon sun

Coppet describes the man sent by Milan Questura as ‘a bel tocco di uomo’ (‘giant man’): could he be identified as Torsello?

Source: Guerin Sportivo, 22/09/1926, p. 2

Moving to late 1933, the Archivio di Stato papers also shed some light on a big controversy that shook not only the local sports world but also the political community of Milan. During that year, there were a lot of rumours about the building of a new city stadium, since the Arena Civica was judged too small by the players and for the upcoming 1934 Littoriali dello Sport ‘Fascist University Games’.

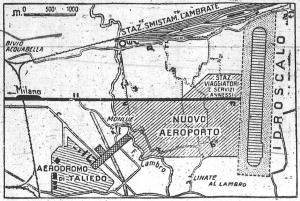

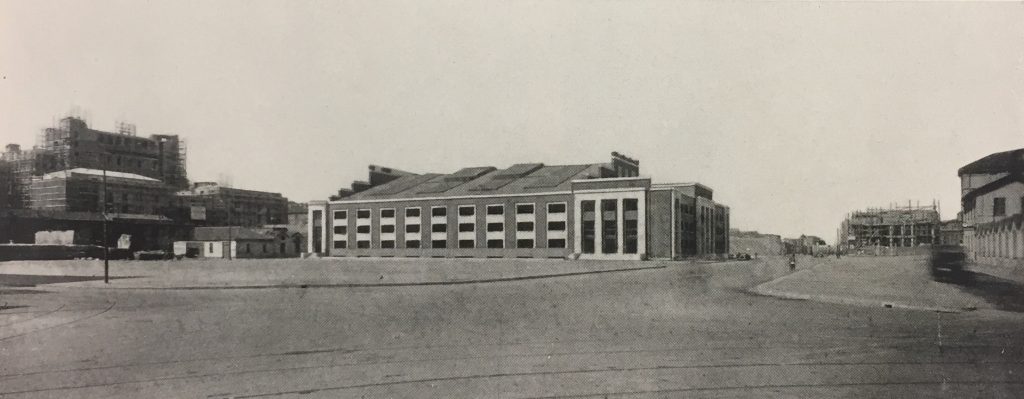

A wonderful map depicts a huge project: a new 100.000 stadium that was planned to be built at the core of a whole new Centro Sportivo dei Littoriali ‘Fascist University Games Sports Centre’, in an area between Viale Michele Bianchi (today Viale Forlanini), the Lambrate rail marshalling yard and the Idroscalo.

How the area looked one year later, in 1934, when the Idroscalo was ready to host rowing events:

a sports centre in the middle of nowhere …

The Lambrate rail marshalling yard is on the right (n. 7), the main road on the left (n. 1)

Source: Il Canottaggio, Aprile 1934, p. 3

In June 1933, the newspapers wrote about a new project: a new airport (today the Linate International Airport)

which would replace the old Taliedo Airport

As you can see, north to viale Bianchi/Forlanini, there was still no building

Source: https://bit.ly/36V2VUY

The beginning Viale Michele Bianchi/Forlanini in 1930s:Idroscalo is on the horizon

The Centro Sportivo dei Littoriali would be built in the open fields on the left of the main road

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viale_Enrico_Forlanini

The project for the new Centro Sportivo dei Littoriali (May 1933, to be built for May 1934)

Source: f. 1114

A close-up of the previous map. The new 100,000 seating places would be surrounded by many football training pitches, a velodrome, and an athletics centre

Source: f. 1114

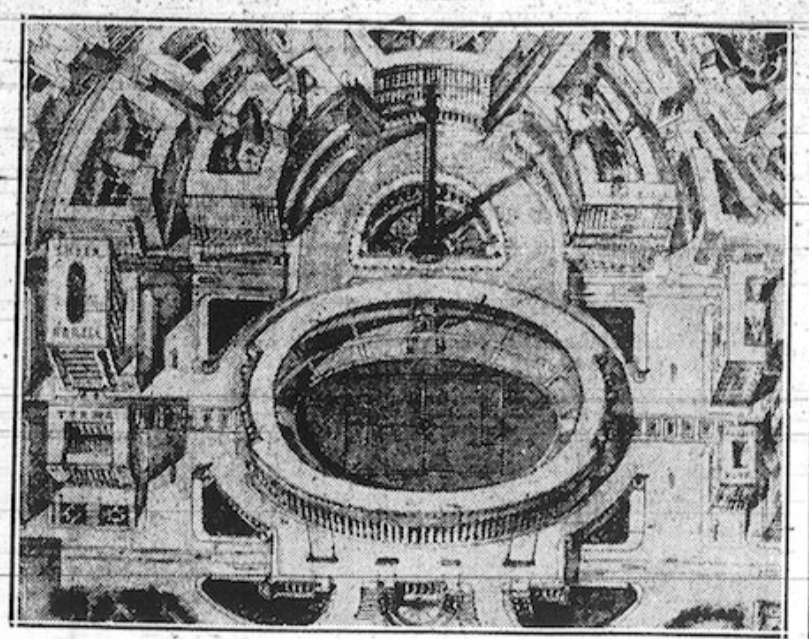

A second, more realistic project was eventually presented by the Municipality of Milan Press Office: a new project by architect De Finetti which would completely renovate the Arena Civica (built during the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy, at the beginning of the 19th century), increasing its capacity thanks to the planned new stands.

De Finetti’s project:

a newspaper reported that one of his inspiring models was the Los Angeles Coliseum stadium, where many 1932 Olympics events took place

Source: L’Ambrosiano, 19/05/1933, p. 3

Then something went wrong …

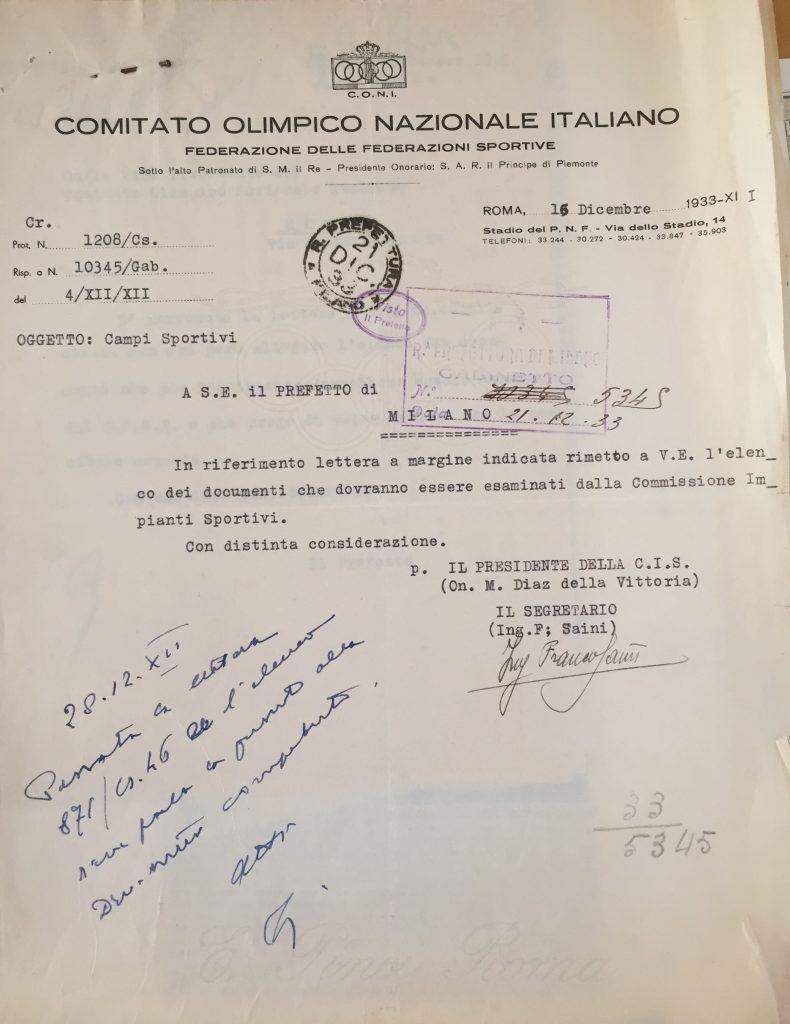

A letter from Marcello Diaz and Saini to the Prefetto di Milano, with some attached documents (the anonymous letter, and the clipping) about the stadium controversy

Source: f. 1114

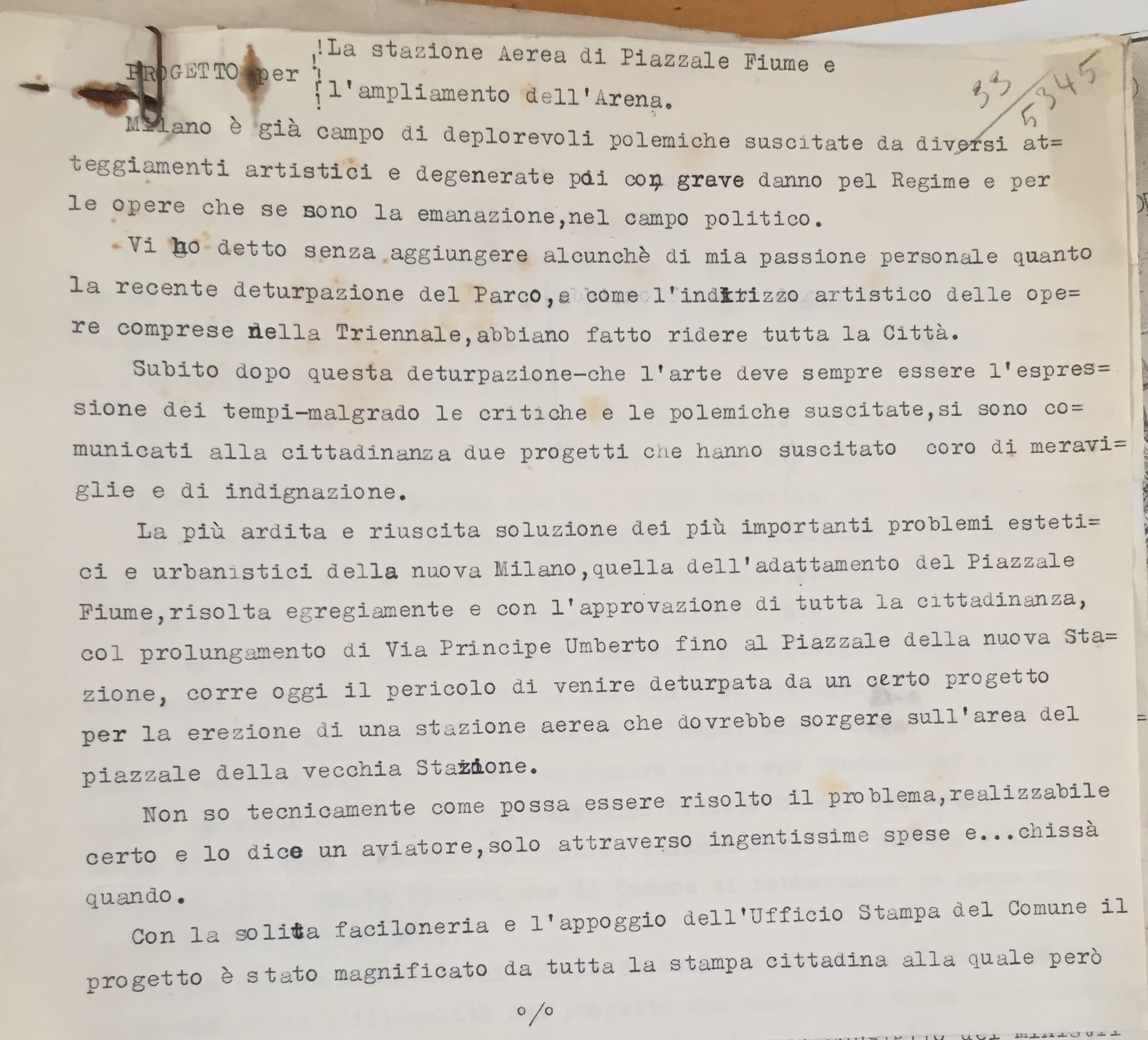

An anonymous and harsh letter was written to attack not only architect De Finetti, but also his political protector, Giancapo, who was at that time Head of the Municipality of Milan Press Office: the author called him ‘the éminence grise of the Municipality’, implying that Mayor Marcello Visconti di Modrone was unable to control him. After complaining about the new buildings in town (such as Palazzo dell’Arte, built for the Triennale in May 1933 on project by Giovanni Muzio: for a Brunilde Amodeo’s photo in front of it, see https://bit.ly/2yKHIOL ), which had somewhat departed from the traditional architecture style, the author said that the Milanese people would never stand for the destruction of the old Arena, defined as the third favourite building in town, after the Duomo and the Castle.

-

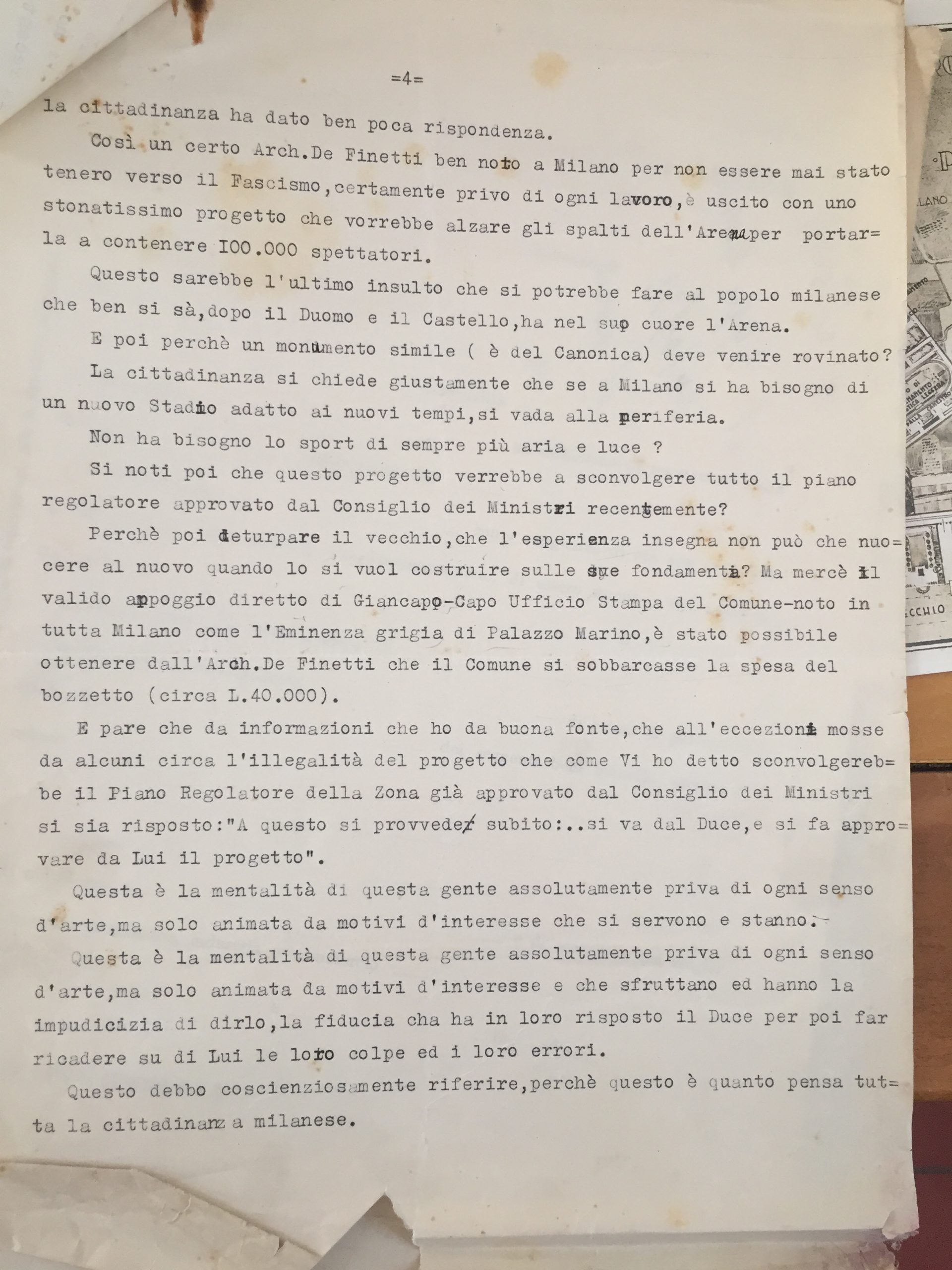

The letters objecting to the De Finetti projects

The author, who claims to be an aviator, recalls the antifascist ideas of the architect, who had asked 40,000 lire for his project. In the end, the author says that Giancapo and Finetti, when asked about the problems of their project with the new Milan master plan approved by the government, would say that there would be no problem: if Mussolini would like it, the master plan would be changed!

Source: f. 1114

The Arena Civica, in 1935

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1198351406450774017

In the end, Mayor Visconti di Modrone had to abandon De Finetti’s project: it was far too controversial, for Milan …

-

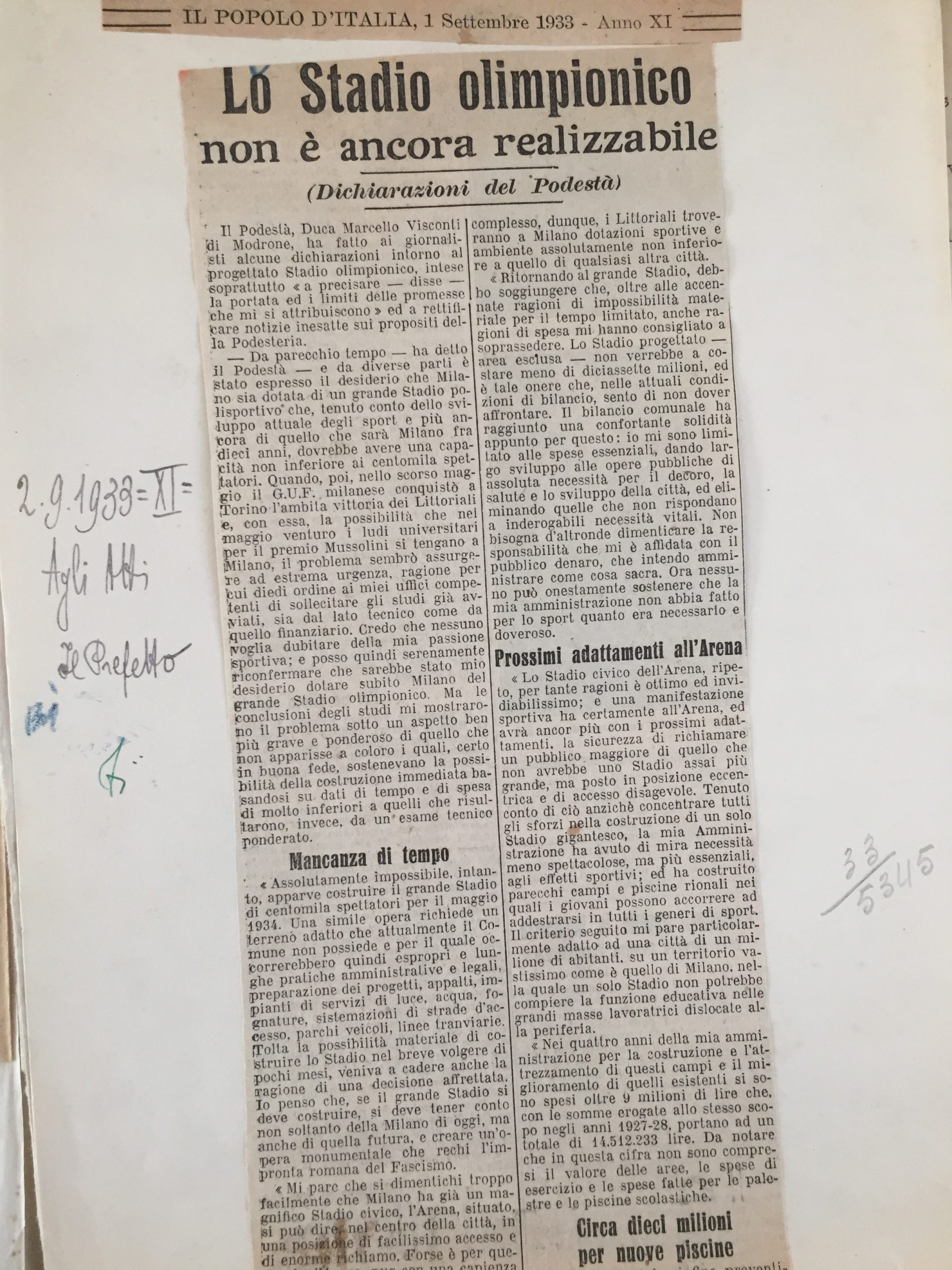

In these clippings from Il Popolo d’Italia (01/09/1933)

Mayor Visconti says the new stadium would not be ready for May 1934. In addition to this, it would cost too much (17,000,000 lire): and as mayor, he prefered to invest Municipality funds into more democratic projects, such as local football/athletics pitches and swimming pools

Source: f. 1114

The new civic swimming pool Cozzi, in a 1935 photo

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1198348964313141249

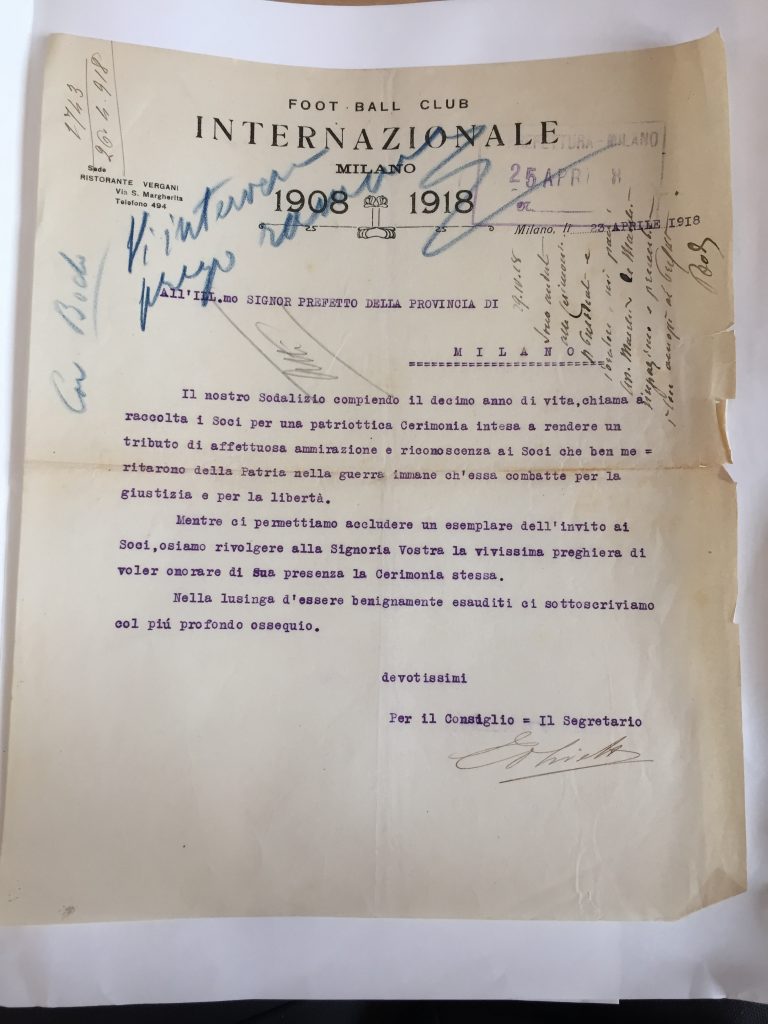

The 1933 stadium controversy can be seen as a big example of the interplay between sports and local politics: yet the Archivio di Stato hold a lot of similar examples, especially when those concerned are not politicians, but members of the sports community. In a letter written in April 1918, the Secretary of FC Inter, in relation to the club’s 10 year anniversary, calls all members (and the Prefetto too) to a ‘patriotic ceremony’ in order to celebrate all those Nerazzurri who served their Country during the on-going war ‘for justice and for freedom’.

Please note the headline, celebrating the 10th years of life of the Nerazzurri team

Source: f. 1116

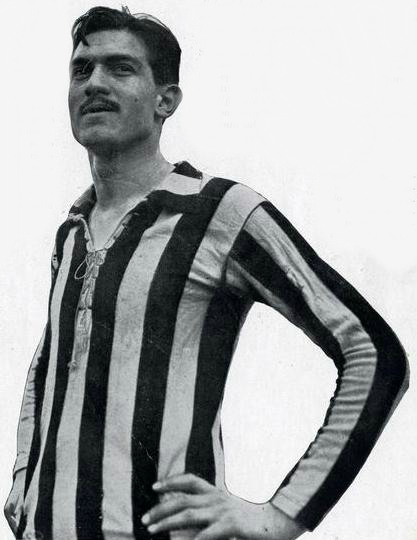

War affected the team of FC Inter itself

In June 1916 the midfielder Virgilio Fossati, who was the first-ever star of the Neroazzurri team, fell on the Alps front, as Captain of the Italian Army

His corpse was never found

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virgilio_Fossati

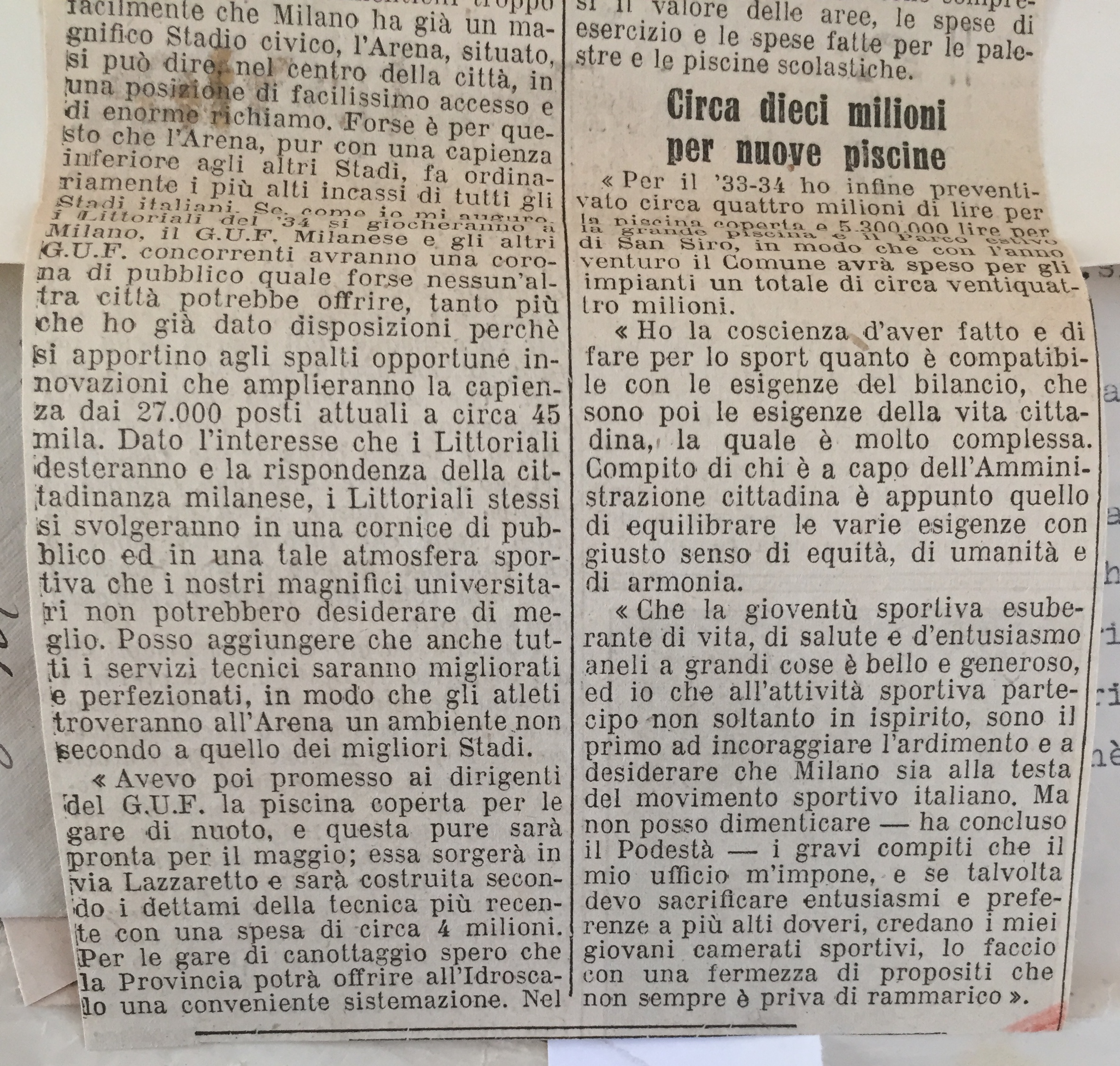

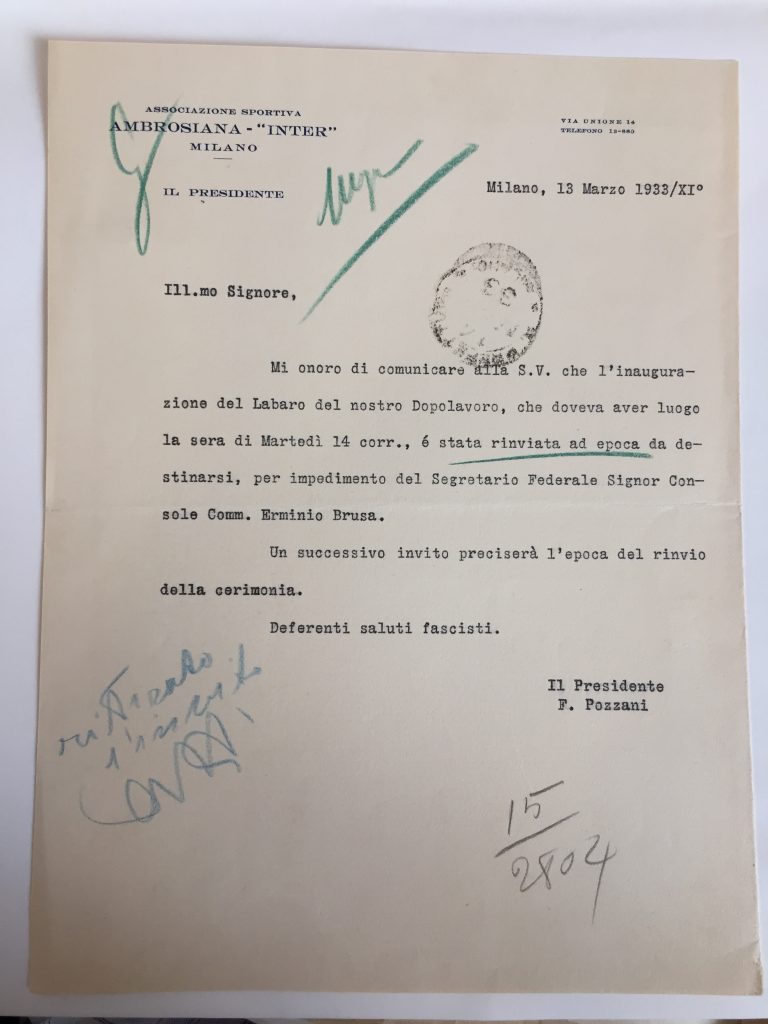

Some years later, FC Inter sent another invitation to the local Prefetto, which is interesting when evaluating the establishment of the Fascist regime and its social agencies. In 1933, the Dopolavoro ‘workers’ club’ (see https://bit.ly/3dkj3QI ), founded among FC Inter employees, was planning to install its own labaro ‘Fascist banner’: the Milan Federale ‘Fascist local chief’ Brusa was going to perform the inaugural raising of the banner. For this reason, FC Inter President Fernando Pozzani (who would go on to be sympathetic to the first-ever Italian female footballers, and later became the President of former calciatrice ‘women’s footballer’ Rosetta Boccalini as Ambrosiana basketball team player: see https://bit.ly/2Z4GRCj), invited the Prefetto to join the ceremony.

-

Pozzani’s invitation to the Prefetto

Source: f. 1116.

-

Some days later, because of Federale’s indisposition, the ceremony had to be postponed

that’s what Pozzani wrote to the Prefetto, concluding his letter with ‘respectful Fascist greetings’

Source: f. 1116.

The labaro of a Milanese Fascist Dopolavoro

Please note the Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro (OND) black logo at the centre of the national Italian flag

Source: https://www.kubel1943.it/foto/output.photo.3.2011.05.25.jpg

Pozzani was not only a powerful sportsman as President of FC Inter, but also a quite ironic man. In June 1937, after the umpteenth bad final result of the Nerazzurri (7° place in Serie A), he declared to the Lo Schermo Sportivo journalist that he was going to ‘give charity’: in fact, ‘some maintain horses for the races, some maintain sugar daddies, and I’m living out my whim maintaining footballers!’ One week later, the sports weekly published the cartoon shown below – where a poor guest of Pio Albergo Trivulzio (the most famous Milanese asylum for old people, called by everyone in town ‘La Baggina’) asks Pozzani:

‘Why don’t you give charity to us old and poor people, instead of doing it to the young football stars?’

Source: Lo Schermo Sportivo, 29/06/1937, p. 2

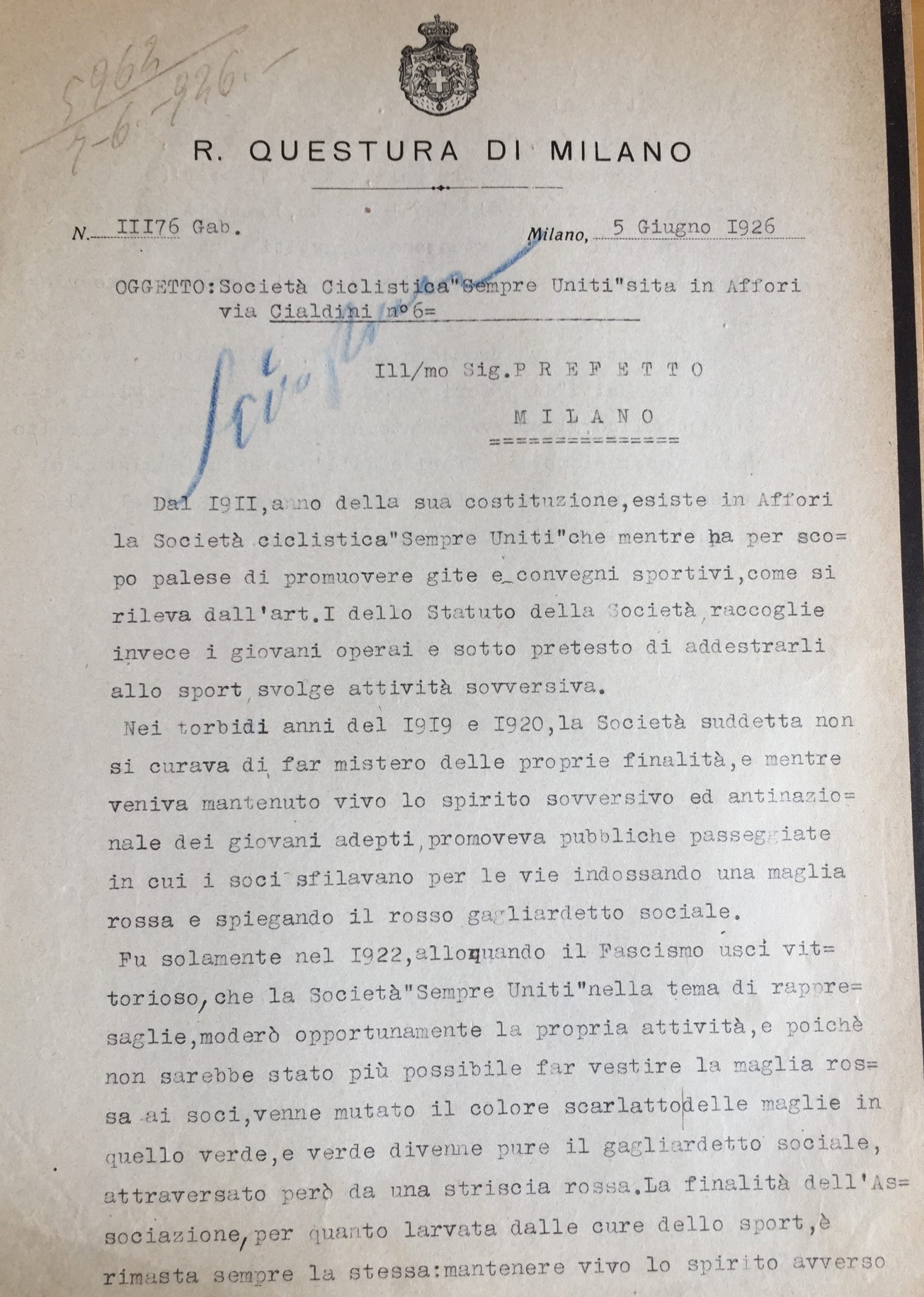

In the years following 1925, all not-Fascist sports associations were shut down by the new regime: thanks to the Milan Archivio di Stato’s papers it is possible to follow the whole closing down process of two of them.

At the end of 19th century immigrant workers founded in Affori (now a northern suburb of Milan, it was an independent Municipality at that time) the Cooperativa Sempre Uniti ‘Forever together Cooperative’, a left-wing mutual aid society. The society had many leisure activities, including a renowned cycling team (founded in 1911), members of which would wear a red shirt.

The bar of Cooperativa Sempre Uniti, some years later

Source: http://www.osteriadelbiliardo.com/p/la-storia.html

After the leggi fascistissime ‘freedom-destroying laws’ of the previous year, in 1926 the Fascist regime could no longer tolerate the existence of such sports associations, despite the desperate last-ditch attempt of Sempre Uniti to cover-up their political identity by changing the cyclists’ shirt from red to green, but still including a red stripe.

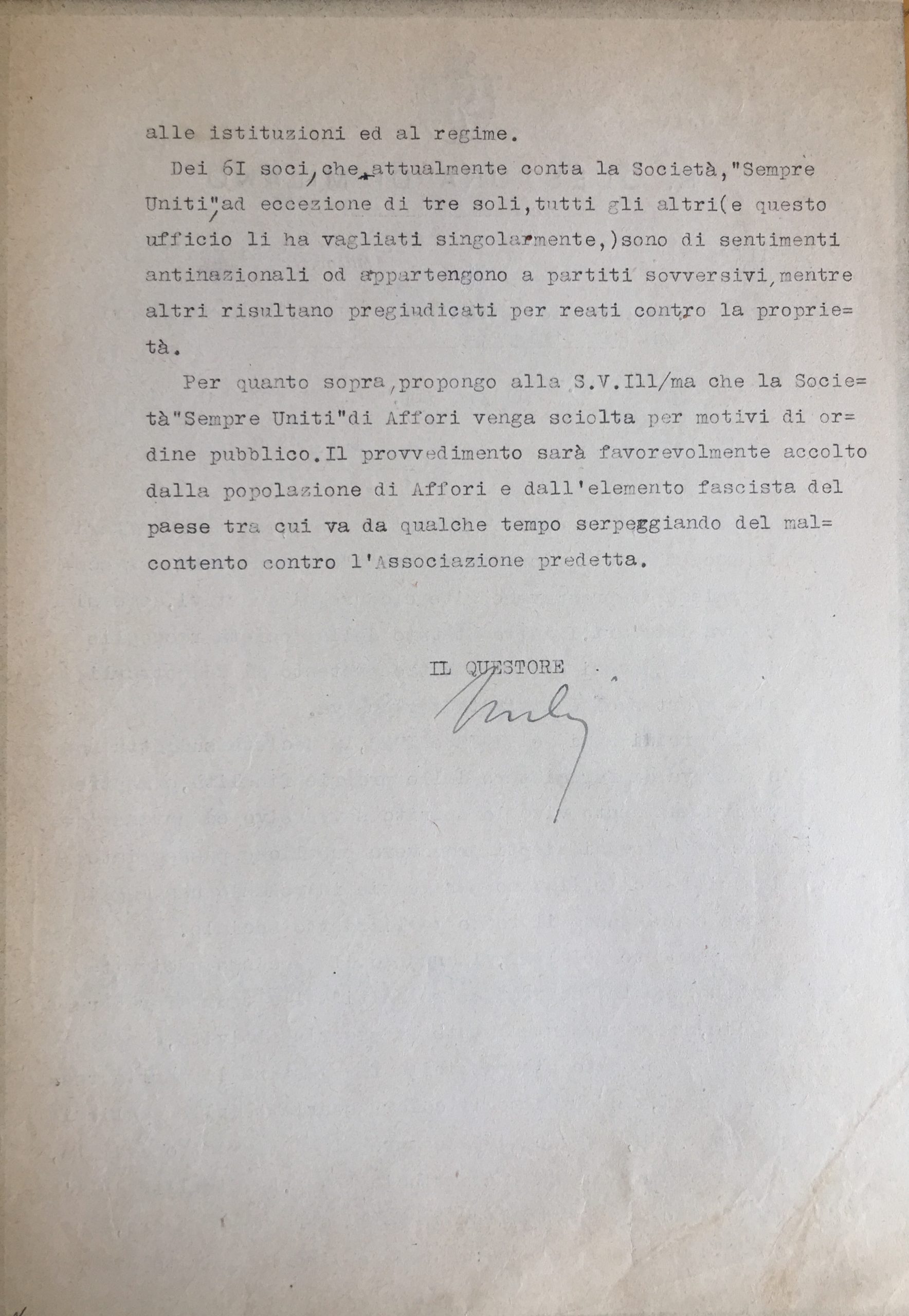

The Questore denounces Sempre Uniti, writing that the sports activities were just a cover for their political activities among young mill workers. After some investigation, just 3 Sempre Uniti members from 61 were recognized as not anti-Fascist nor convicted felons. In his conclusion, the Questore writes that the eventual dissolution of Sempre Uniti would be welcomed by Affori Fascist fellows Source: f. 1223.2

-

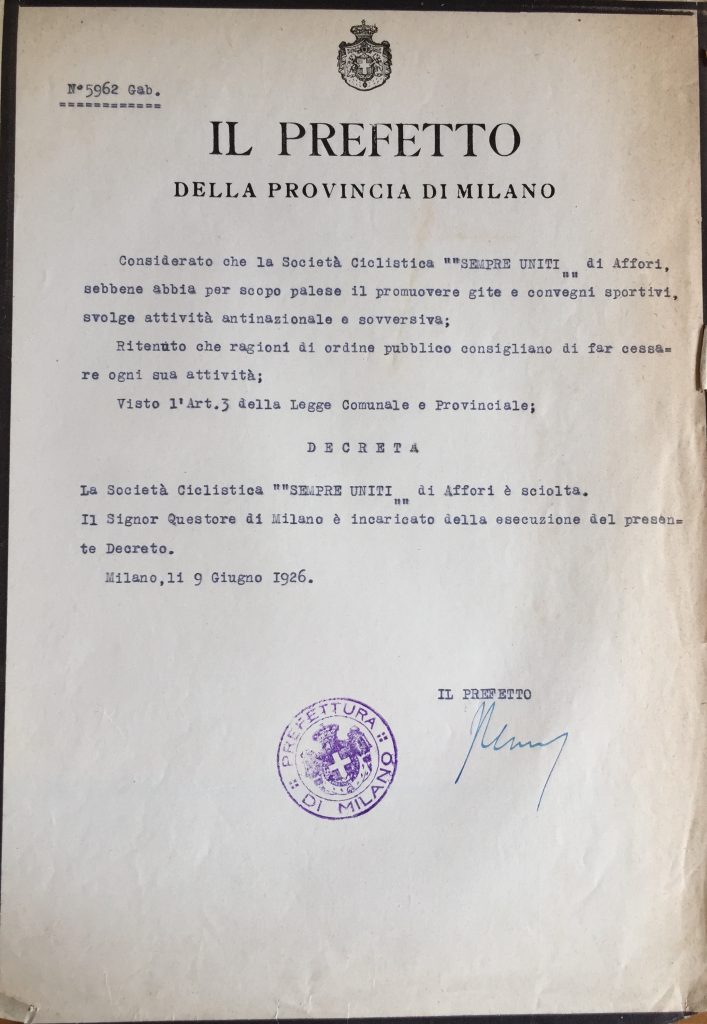

On 9 June 1926, the Prefetto decree the dissolution of Sempre Uniti association

the Milan Questore should be the executor of such decree

Source: f. 1223.2

-

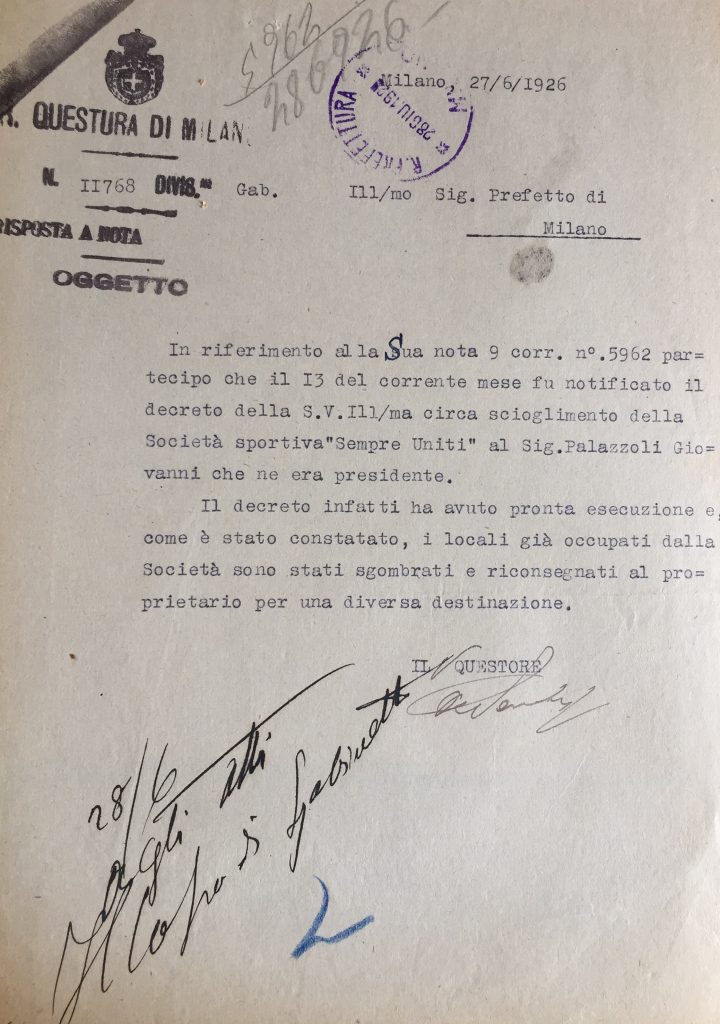

On 27 June 1926, the Questore writes to the Prefetto that the job was already done

the Sempre Uniti headquarters had been yet cleared and given back to their landlord

Source: f. 1223.2

After 1926, the Cooperativa was turned into a Fascist association

But still, it went on having a cycling department, as we can see in this early 1940s’ photograph took during a mountain trip

Source: https://bit.ly/3nJhQYn

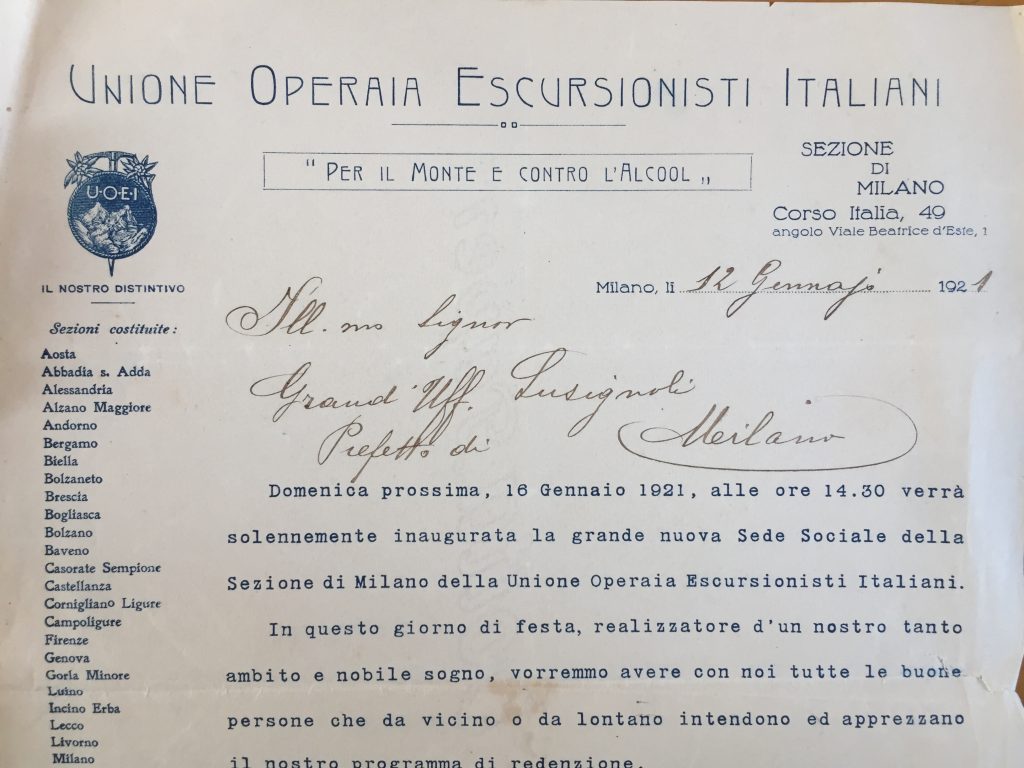

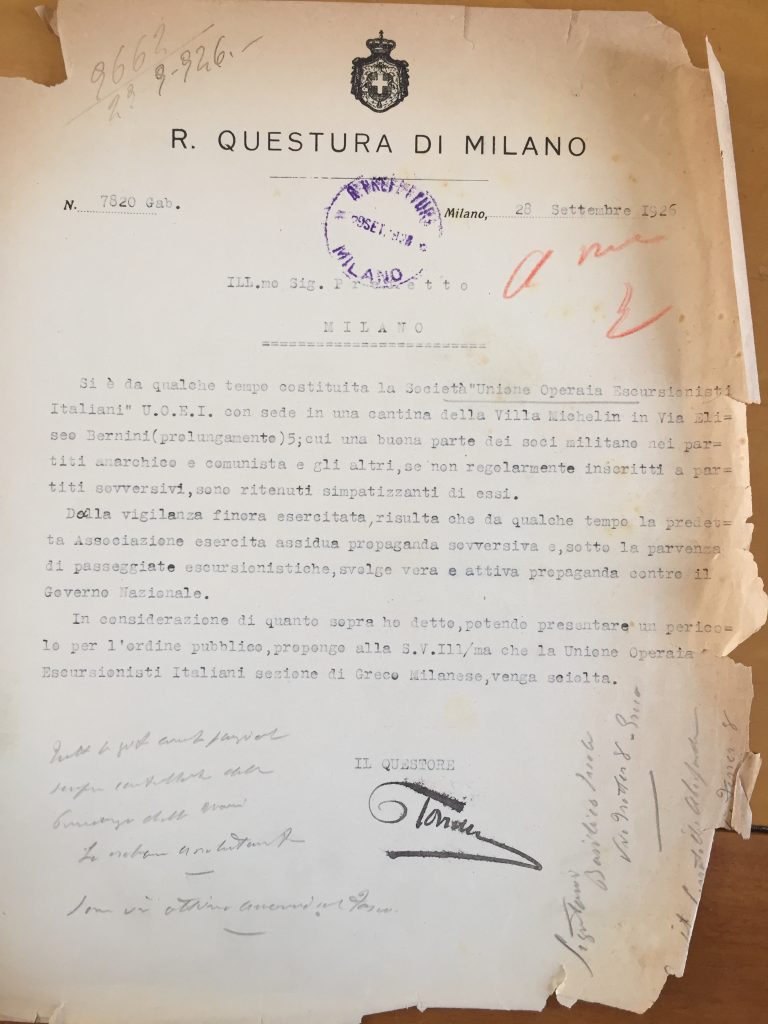

The second case of repression of a sporting club is linked to the Milanese office of a national association, Unione Operai Escursionisti Italiani (UOEI) ‘Italian Workers’ Mountaineering Union’. During 1926 the association, which was founded in 1911 thanks to the help of many Socialist leaders (i.e. Claudio Treves) and associations (Società Umanitaria, Milan), was forced by the regime to flow back into the Fascists leisure associations.

- A UOEI pin; the logo, as Playing Pasts’ readers already know (see https://bit.ly/39mZbdN ), was made up of mountains, an ice-axe and some edelweiss flowers Source: https://bit.ly/2IpP92N

- OUEI had also an inner skiing department, as you can see from this silver pin from Milan Source: https://bit.ly/3ktp0wM

A 1922 UOEI silver medal, for the 2nd edition of ‘Marcia popolare alpina’ (Popular Alpine trekking march), ‘Giro Corni di Canzo’.

Source: https://bit.ly/35qPQ4v

Note that in this 1921 letterhead, not only (on the left) the list of local offices alla around Italy, can be seen, but also (at the top) the slogan ‘for the mountain, and against alcohol’

Like many Socialist sporting groups of the 19th and 20th century, UOEI founders thought that sports could help honest workers avoid the social disease of alcoholism

Source: f. 1115.

In September 1926 a Questore wrote to Prefetto with claims that most of the members of UOEI office in Greco (today a Milanese quarter) were Anarchists and Communists. Added to this, the UOEI members pushed explicit political propaganda, even during the sporting events such as mountain excursions. For these reasons, the Questore asked for the Greco UOEI office to be closed.

The Questore letter Source: f. 1115

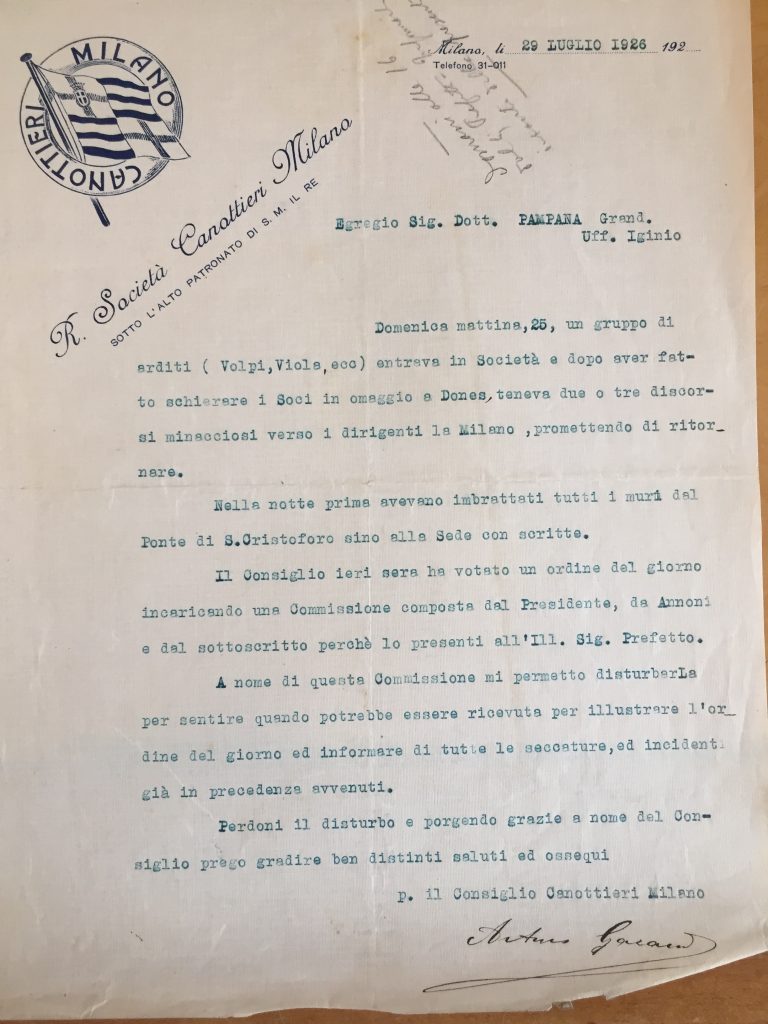

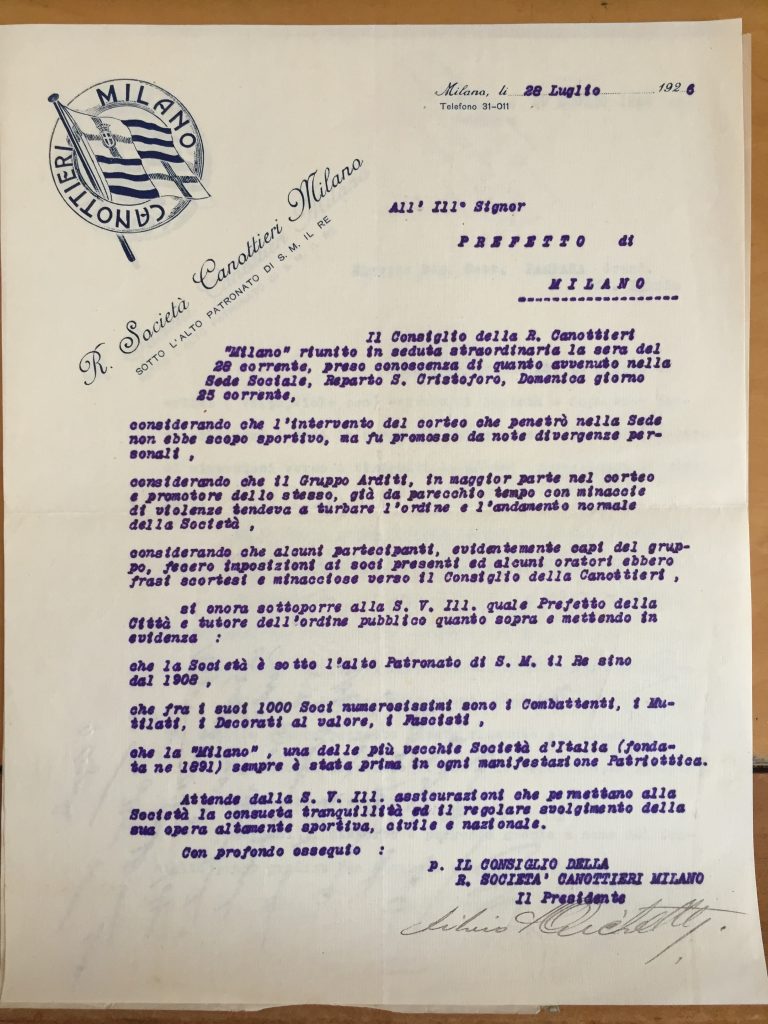

We can follow the sporting effects of Fascists’ seizure of power, via the archives, as it moved to the two Milanese rowing clubs, Canottieri Milano and Canottieri Olona. Some papers relate a story from 1926, when some arditi ‘war veterans’ threatened the Canottieri Milano managers and smearing graffiti on the walls of CM headquarters. In its letter, the Consiglio ‘Executive Board’ of CM remembers not only the protection of H.M. the King and the patriotic spirit of CM members but also that many of them are members of the National Fascist Party. Such assurances could be the only way to achieve the goal to be protected by the state police from the attacks of the regime’s supporters.

- The two 1926 letters

- Source: f. 1117.

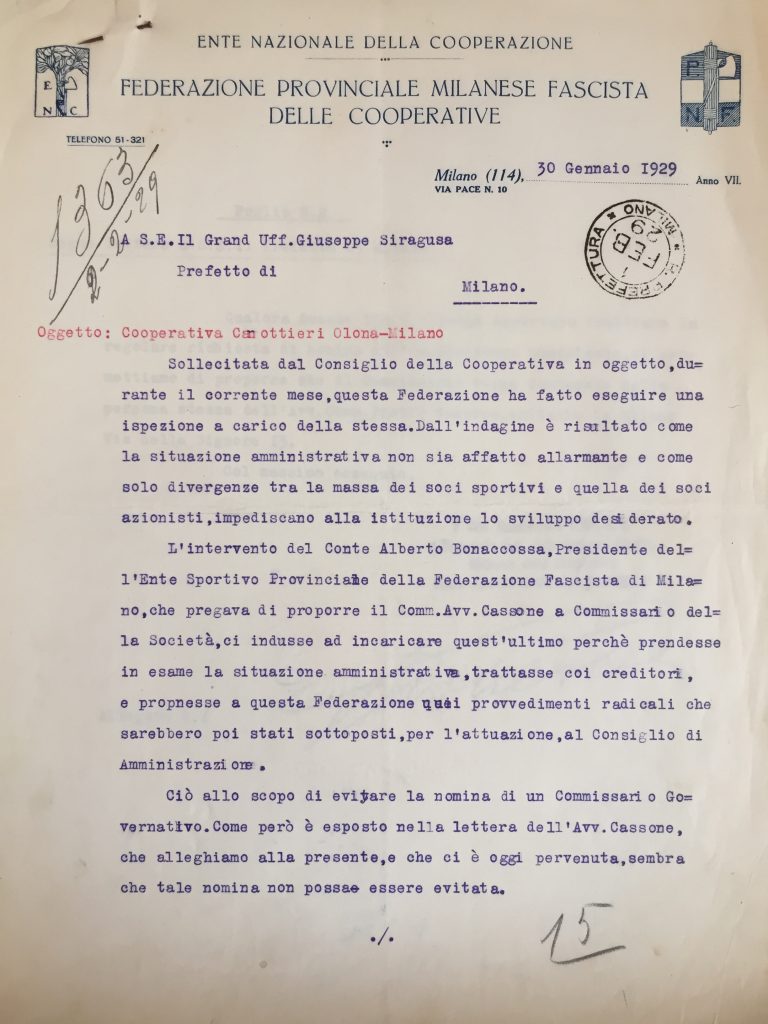

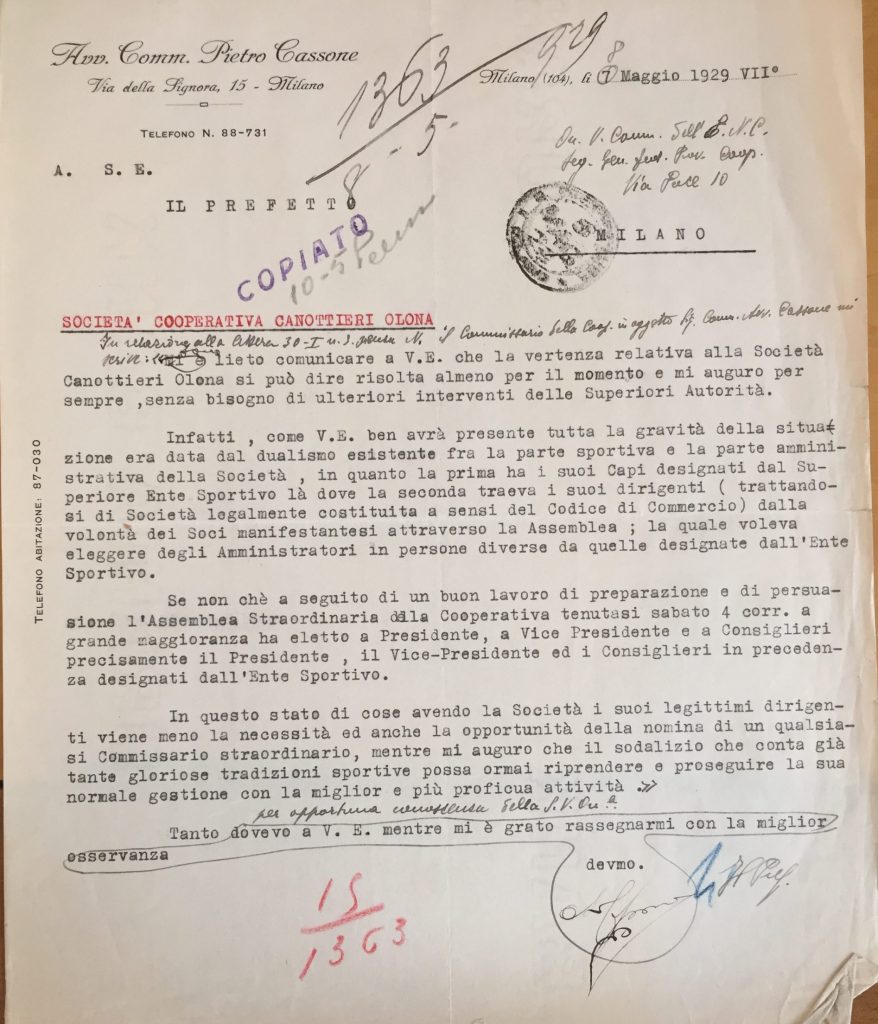

In the following years, the main problem for the Fascist regime was not the explicit political resistance of the sports club, but rather how to find a way to actually control them. Papers relating to Canottieri Olona can give us a good example. During 1929 the local Fascists tried to change the double structure of CO (which was a cooperative): in fact, the head of the sporting department was chosen by Fascist Ente Sportivo, while the head of the administrative department was still elected by the shareholders’ meeting.

-

In this letter, the Fascist office for Cooperatives describes the situation

and how even the powerful sportsman Alberto Bonaccossa (President of Ente Sportivo) couldn’t solve the problem

Source: f. 1117.

-

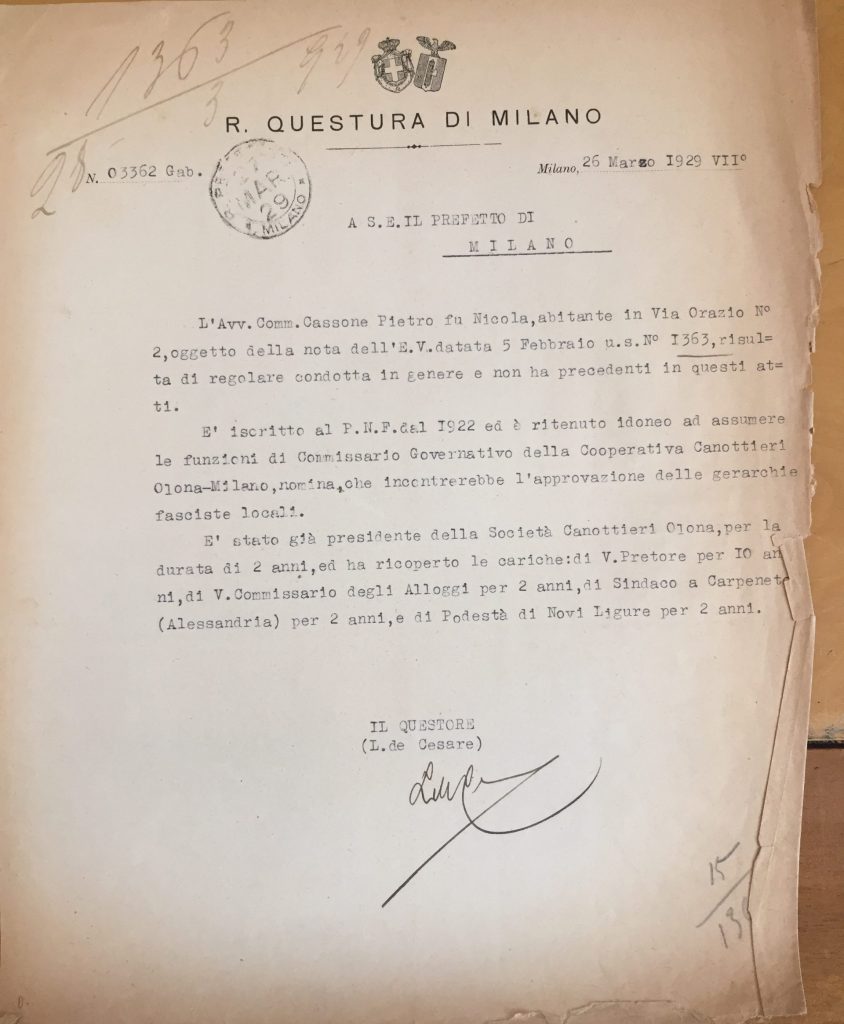

A letter from Questore L. De Cesare to the Prefetto regarding laywer Pietro Cassone

being an uncensored and member of National Fascist Party, so the perfect man to became the CO Special Commissioner

Source: f. 1117.

On May 1929, Cassone could finally describe the happy ending to the Prefetto

Thanks to ‘a good preparation and persuasion work’, the shareholders’ meeting had confirmed all the member of the executive board chosen by the Ente Sportivo

Source: f. 1117.

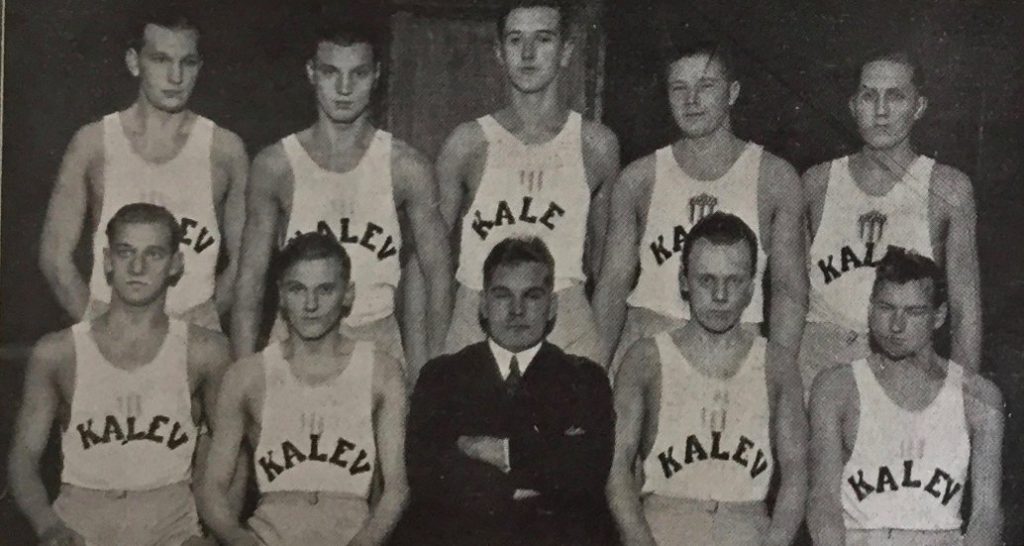

It is well known that the Fascist regime understood very early the importance of international sporting success: every one of them, not only Olympic ones, were seen as increasing the good reputation of Italy abroad, as well as demonstrating to the Italian population that a new winning era was spreading, especially after the national humiliation of 1919, when the allies humiliated Italy at the Congress of Paris. In 1932, the SC Kalev basketball team arrived in Milan to play against a special team composed of players from Lombardy (the region of Milan); the game was hosted at Forza e Coraggio sports centre (see https://bit.ly/2RgfZve ). The journalist known as Zam reported that the Republic of Estonia was so small that it caused its inhabitants to try to develop in height following the example of New York skyscrapers. The 5 ‘string beans’ from Estonia, ‘very good in shaking off and distances shots’, defeated the Italian players 28-23: according to Zam the latter were just amateurs, not accustomed to playing in international games. The final balance of the game however was seen as positive, because a large audience attended the match and the defeat could be considered as a good lesson for the Italian players, in the path of the obvious up-coming victories to come.

The Kalev team (1932), in a photo from the article by ‘Zam’

Source: [unknown magazine], 31/01/1932, p. 158.

In this video shot on January 1932, the Estonian team (playing against the Lazio players in Rome) are depicted as the National team … Source: https://youtu.be/eQ6BQqWHcco

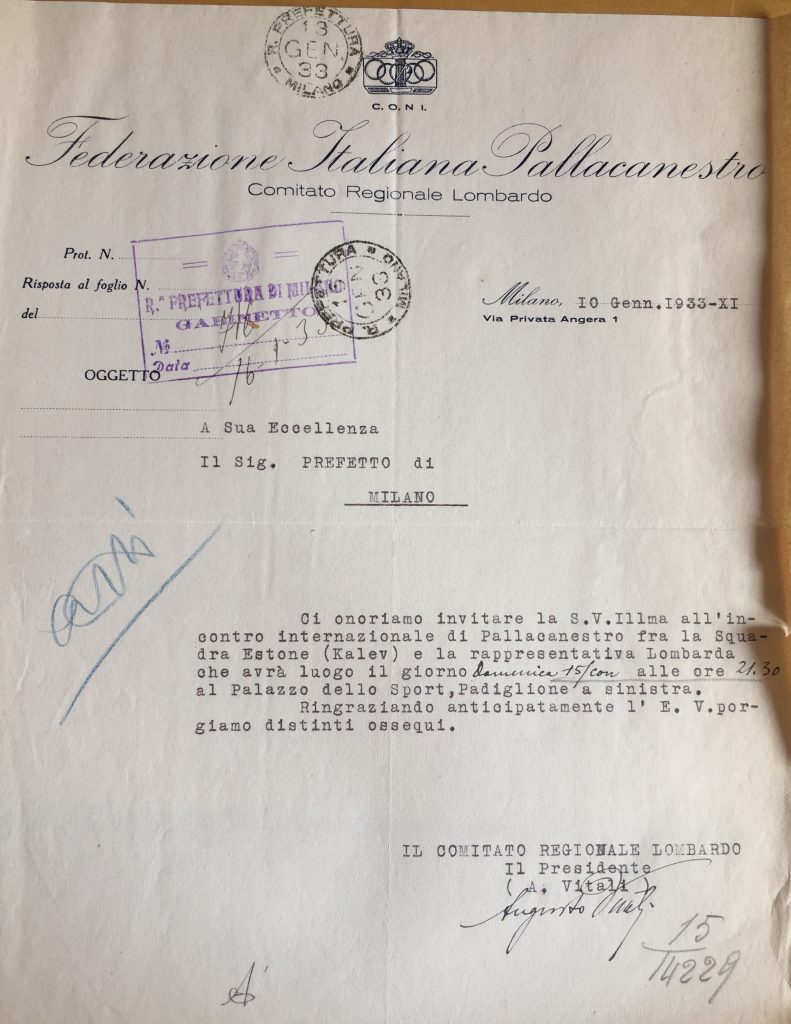

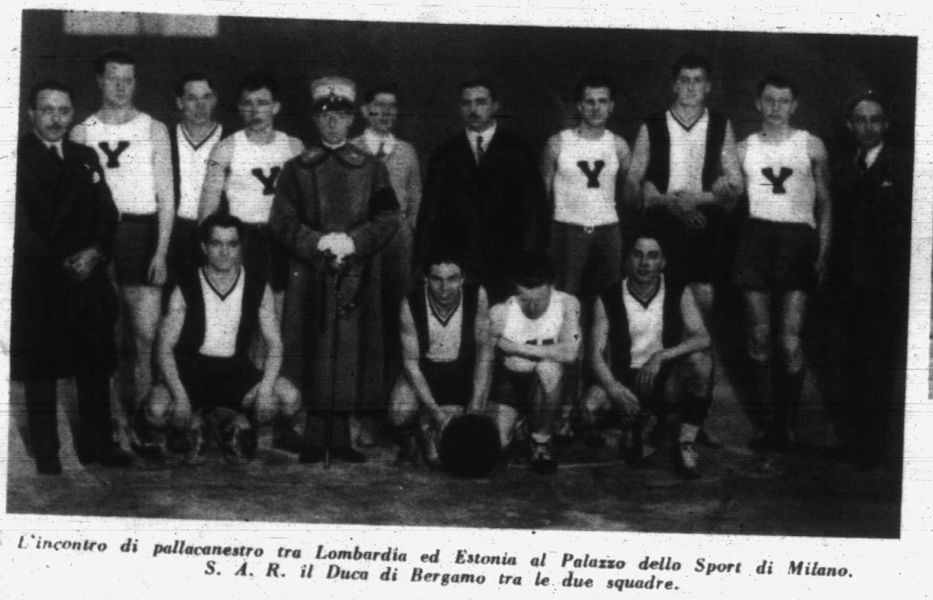

One year later, the rematch, played on 15 January 1933 in Milan, saw the Lombardy team (composed mostly of players from Dopolavoro Borletti) play at the Palazzo dello Sport basketball pitch against an Estonian team, which was no longer called SC Kalev, but rather NMKV (YMCA) Tallinn. Among the crowd there was the predictable presence of Duca di Bergamo, who ‘fraternized with both teams’ players’, including Sergio Paganella – was he ‘coach Sergio from Borletti’ who trained Marta and Rosetta Boccalini some years later (see http://bit.ly/2S9K4ff)? The Italian players defeated the Estonians 35-22: the goal of an international victory was finally achieved!

The invitation by Federazione Italiana Pallacanestro (Italian Basketball Federation) to the Prefetto of Milan to watch the match, scheduled at 9.30pm

Please note that the Estonian team is called ‘Kalev’ because that was the team that played a year before against the Lombardy team!<br<Source: 1118.

The Duca of Bergamo among the players (Estonians wearing a ‘Y’ shirt)

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 29/01/1933, p. 15.

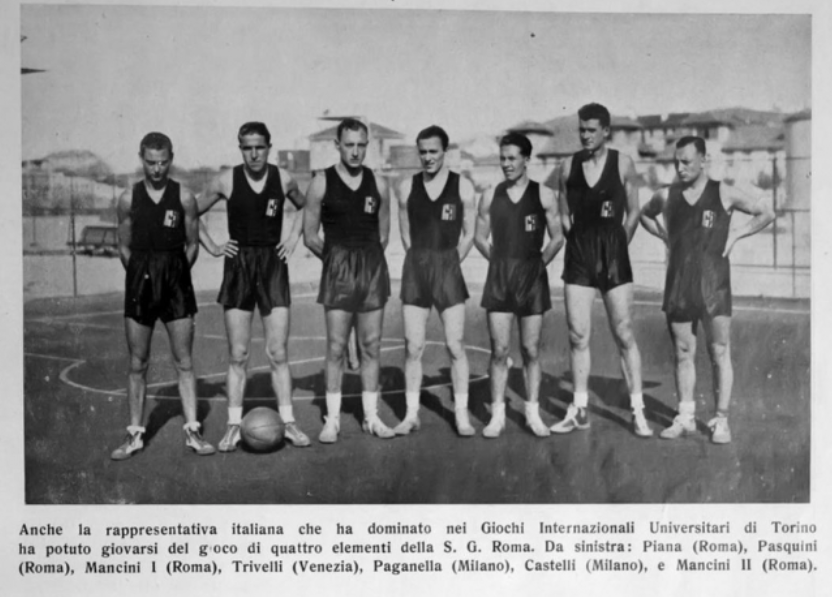

Sergio Paganella (3rd from the right) with his teammates of Italy National University team at the World University Games, held in Turin in mid-1933

Please note the black (Fascist) colour of the shirt, instead of the traditional azzurro ‘light-blue’

Source: https://www.museodelbasket-milano.it/leggi.php?s=&idcontenuti=218

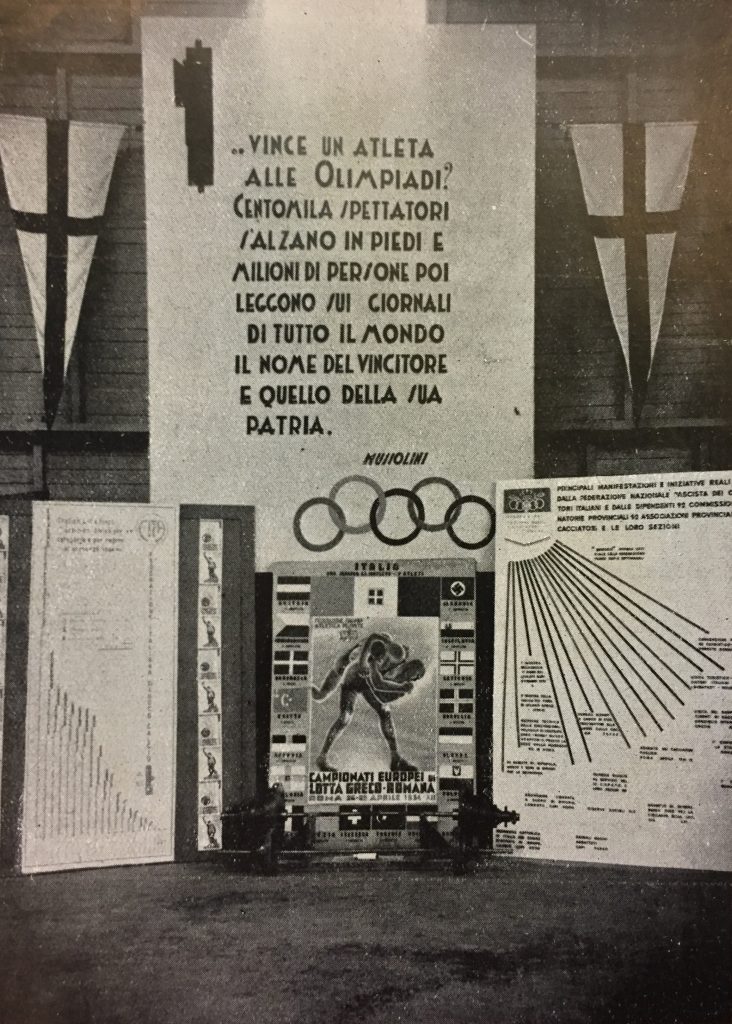

Despite this, the Olympic Games remained the biggest chance for an Italian athlete to glorify the name of his country. As Mussolini himself said: ‘Does an athlete win at the Olympic Games? An audience of 100.000 rises up, and then millions of people all around the world read on newspapers the name of the winner, and of his country’.

The sentence by Mussolini, written at the entrance of Mostra dello Sport ‘Sports Exhibition’ held in Milan (1934)

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, May 1934, p. 37.

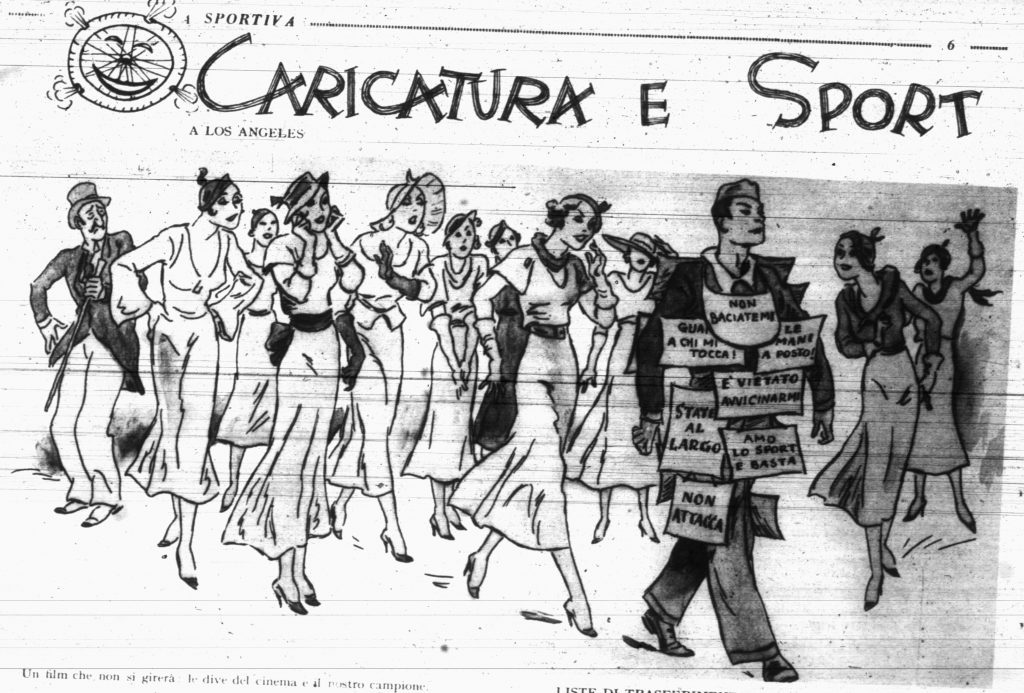

After Amsterdam 1928, Italy worked hard to improve it’s Olympics performance at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics …

Original captions says

‘A movie that won’t be shot: cinema divas and our champion’

Note the sign hanging on the the Italian man, wearing the official 1932 Olympic coat

‘Don’t’ kiss me!, ‘I love only sports’ and ‘Keep away!’

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 10/07/1932, p. 6

Notwithstanding these concerns, Italian athletes (who were all male, after the decision of the Italian Olympic Committee not to take to America Ondina Valla or any female athlete) met Hollywood divas, such as Anita Page, here with Poggioli, Contoli, Vandelli, Tommasi and Tabai

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, Gennaio 1933, p. 59

Anita Page was so naïve that she agreed to make a Romane salute with the Azzurri fellows

a little example of how the ‘Mussolini’s Boys’ succeeded in winning over the US audience, in the summer of 1932

Source: L’Illustrazione Italiana, 04/08/1932, p. 210

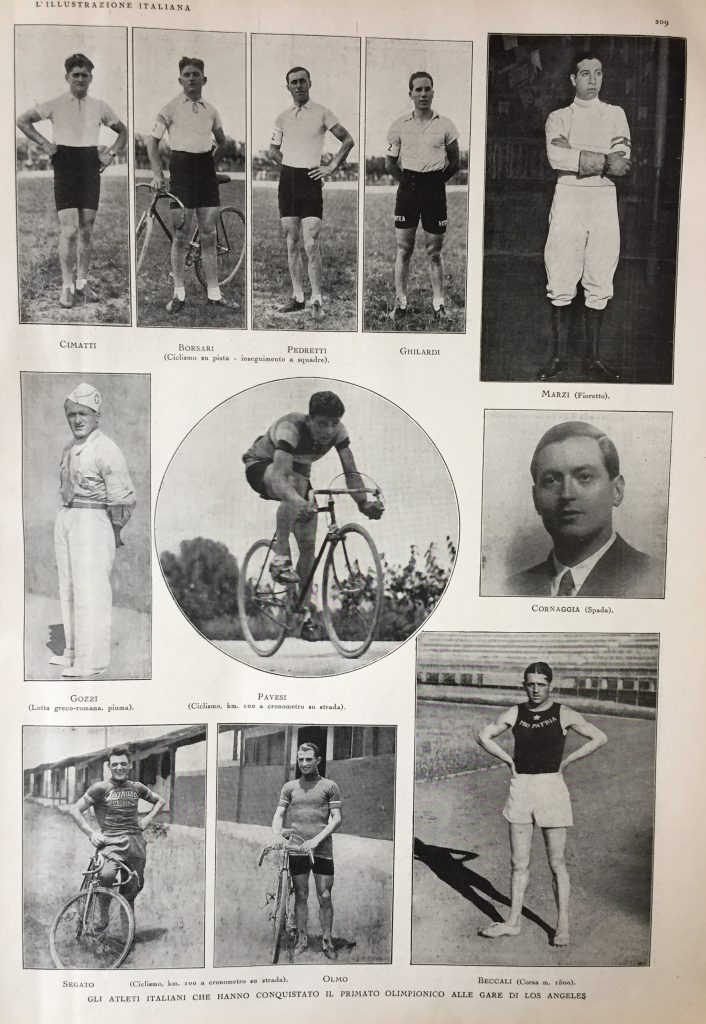

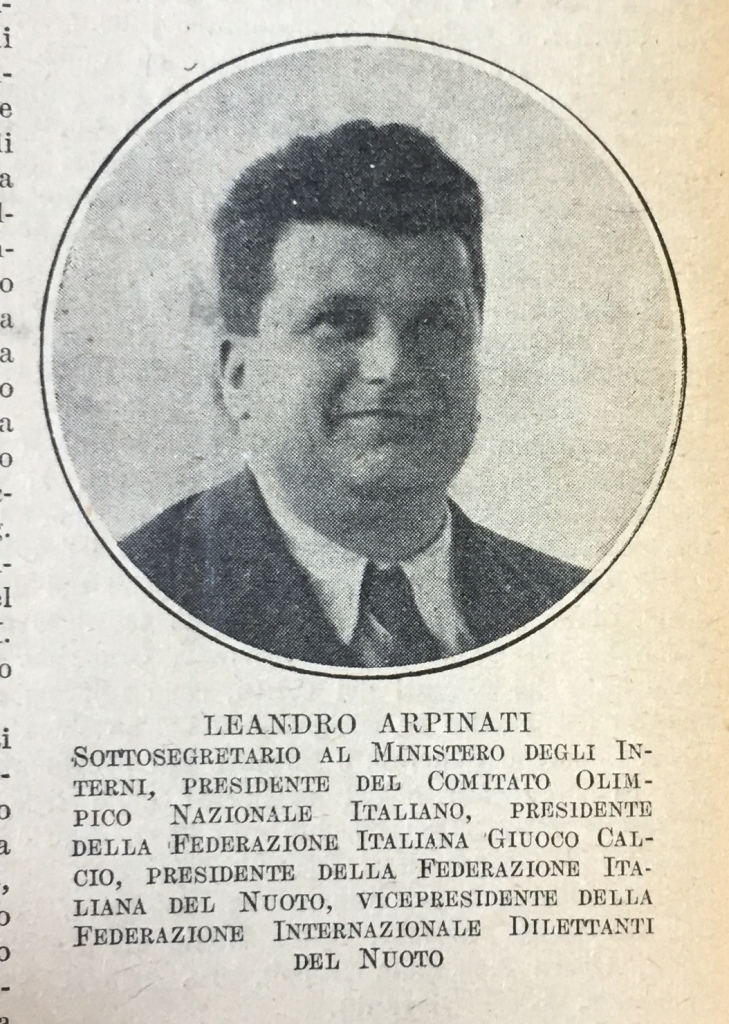

Thanks to the hard management work of Leandro Arpinati, President of the Italian Olympic Committee (CONI), Italy were ranked 2nd in the final table (still the highest in the history), winning 36 medals (12 gold, 12 silver and 12 bronze), almost twice as much as in 1928.

A whole page full of Italian gold-medals winners …

Source: L’Illustrazione Italiana, 04/08/1932, p. 209

The complete list of Arpinati’s charges at the end of 1932

State Secretary for the Interior (since Mussolini was the Minister, he played as the real Minister)

President of the CONI;

President of the Italian Football Association (FIGC)

President of Italian Swimming Federation (FIN)

Vice-President of International Amateur Swimming Federation

Source: Almanacco della Gazzetta dello Sport ed. 1933, p. 13

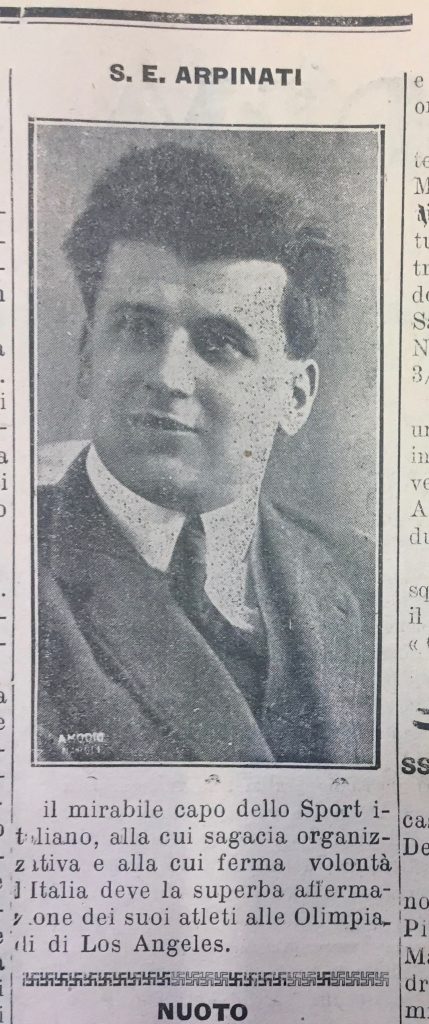

The Naples-based sports newspaper, La Voce Sportiva, wrote at the beginning of September, in praise of Arpinati

‘the wonderful leader of Italian sport: Italy owes his organizational capacity and his strong will the outstanding performance of its athletes at Los Angeles Olympics’

Source: La Voce Sportiva, 06/09/1932, p. 3

Leandro Arpinati was very powerful and successful, yet also had be very careful because he had a lot of enemies: just a few months later, in Spring 1933, he would lose every charge, because of the envoy of Achille Starace, who succeeded in unleashing Mussolini himself against him. The papers in Milan Archivio di Stato show a huge paradox, which was, how the Olympic success, started to become a problem for Arpinati since the return of the Italian winners from the States.

Achille Starace, Secretary of National Fascist Party (PNF)

After Arpinati’s overthrow he became the President of CONI (1933-1939)

In 1945 he was killed by some partisans in Milan, just few days after Mussolini

Source: Annali del Fascismo, January 1933, p. 4.

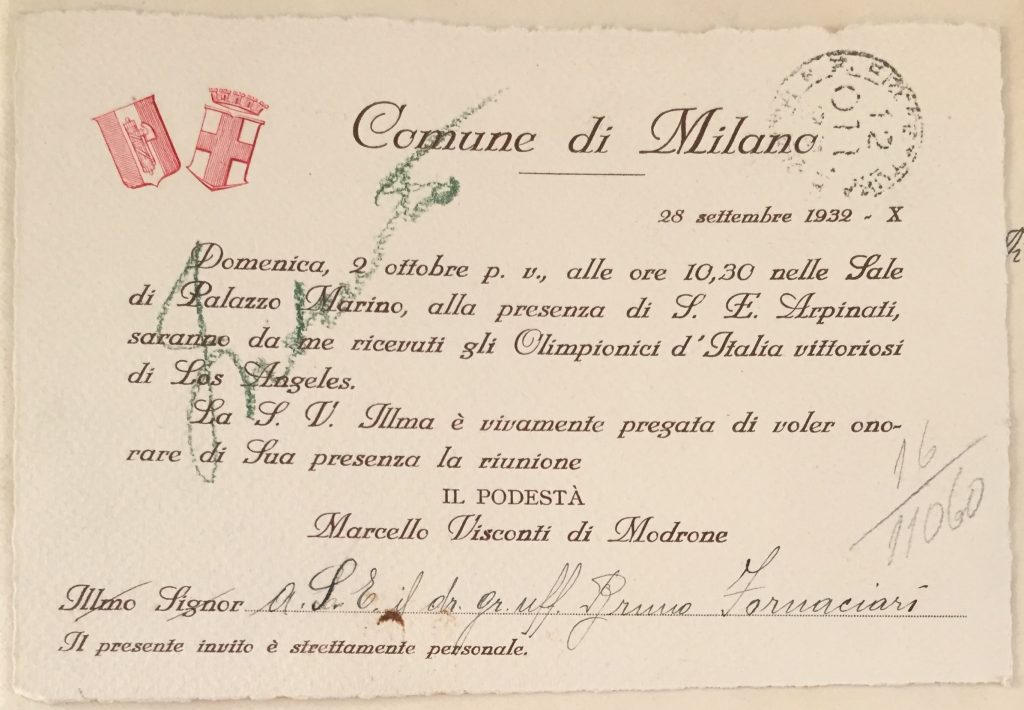

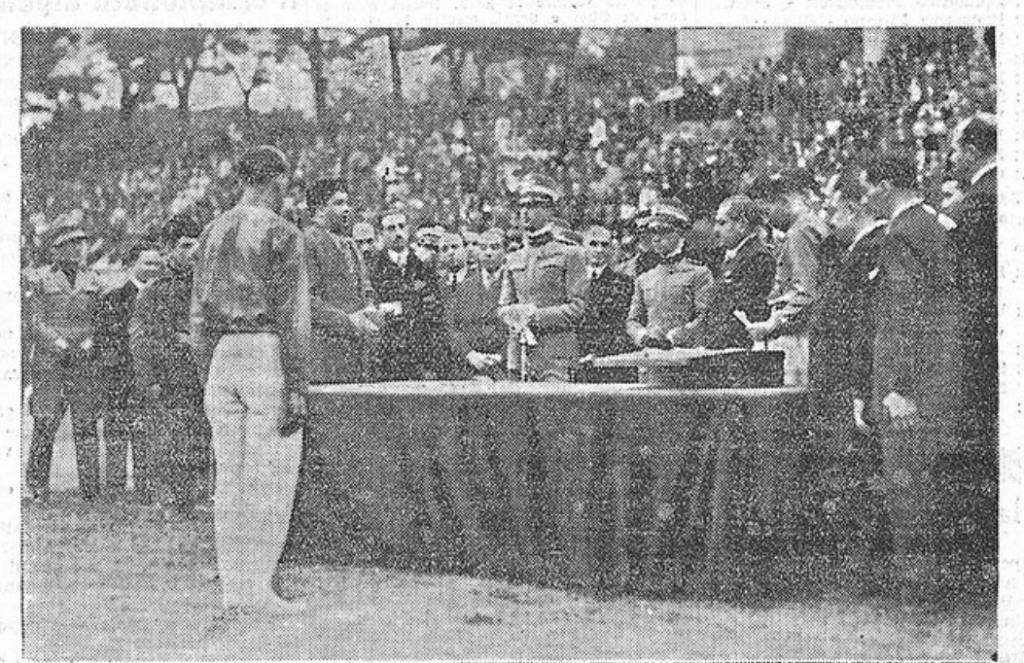

On Sunday 2 October 1932 a big ceremony was held in Milan: the Olympics winners were celebrated by the Milanese people and national and local authorities such as Arpinati (as CONI President) the king’s heir Principe di Piemonte (Prince Umberto of Savoy, who was crowned King Umberto II in 1946), his cousin the Duca di Bergamo, Mayor Marcello Visconti di Modrone.

The Mayor’s invitation to the Prefetto

The Olympic winners would arrive in Palazzo Marino, Milan’s city hall, where they would be hosted by himself and Arpinati

Note in the letterhead, the two shields: the fascio littorio, and St. George’s Cross (symbol of the Municipality of Milan, see https://bit.ly/39mZbdN )

Source: f. 1114.

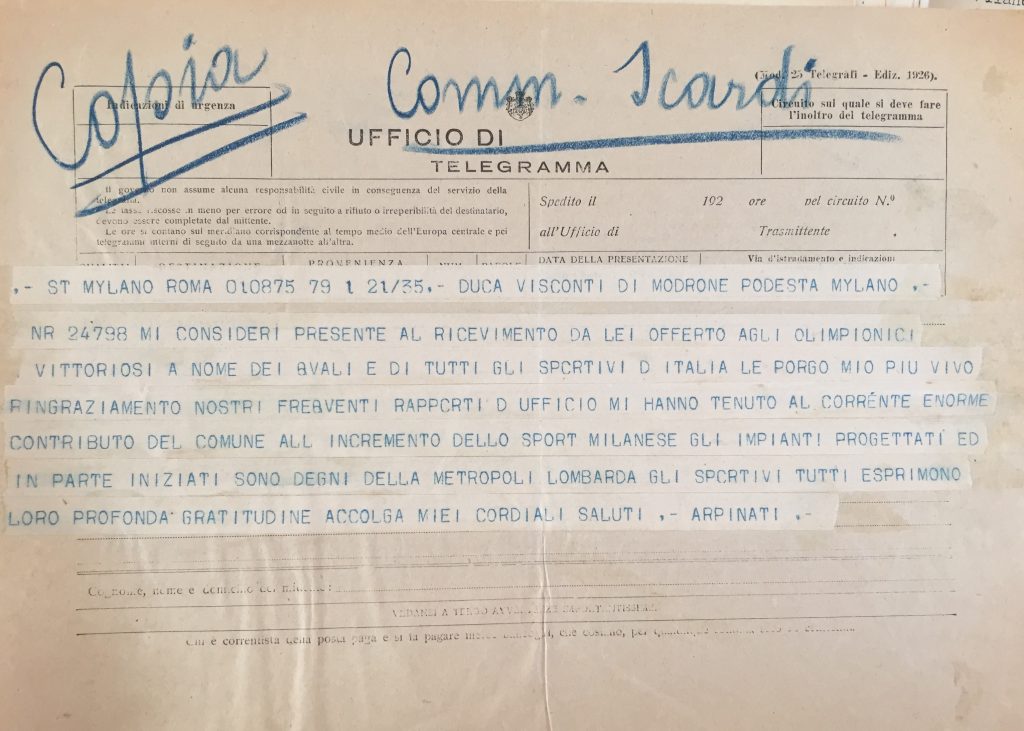

Arpinati confirms to the Mayor his participation in the Palazzo Marino ceremony, praising the ‘outstanding work made by the Municipality in increasing the sporting activity: the sports facilities – both already done, and under construction – are what Milan deserves. For this reason, all sportsmen are very grateful’

Source: f. 1114.

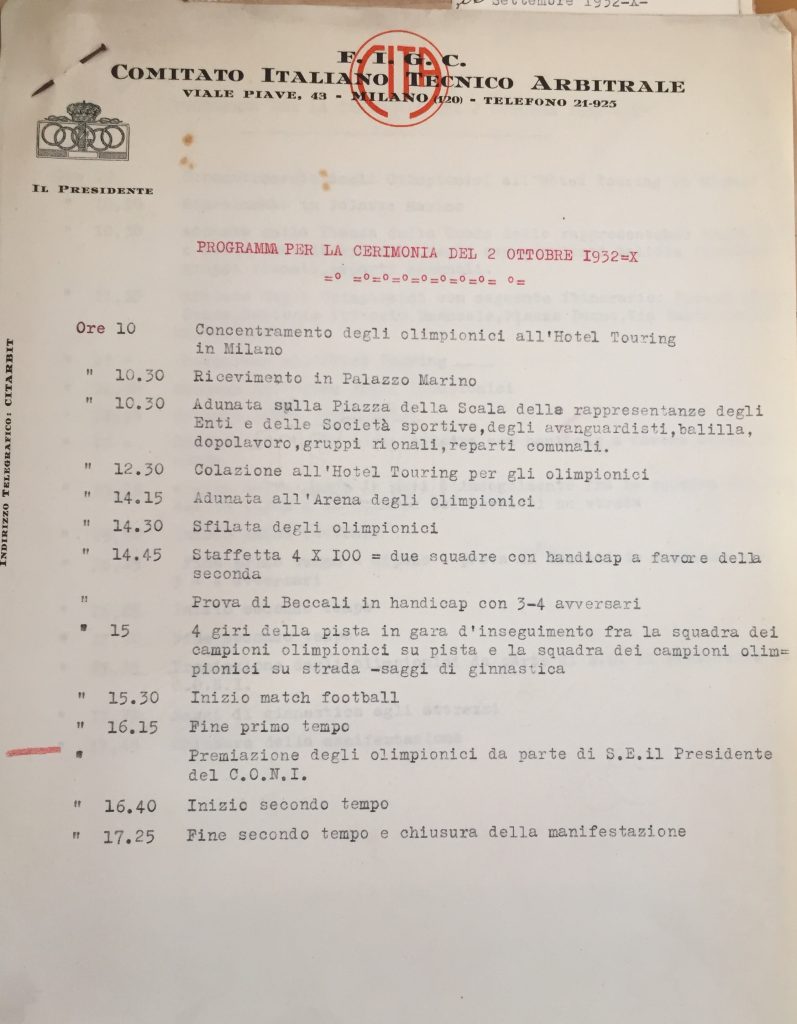

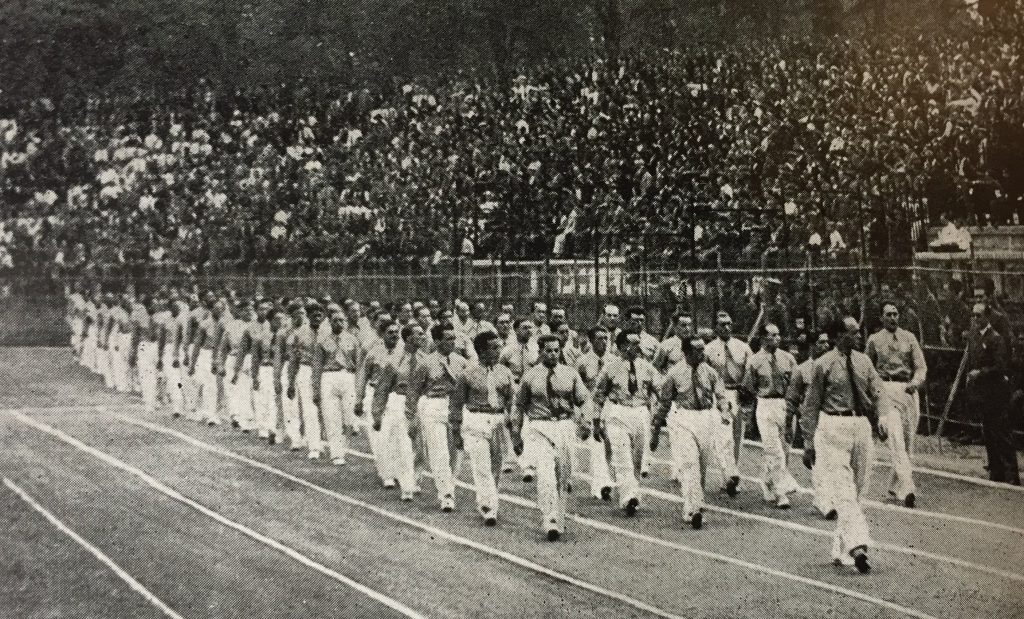

After the ceremony at Palazzo Marino, the athletes were welcomed by the sporting and Fascist Milanese associations in Piazza della Scala, followed by lunch at the Hotel Touring. In the afternoon, they travelled to the Arena Civica: after a parade, some of them (i.e. Beccali) gave a display and a football match took place, at which during half time Arpinati awarded prizes to the Olympics winners.

The complete programme of the day, in this FIGC letterhead

Source: f. 1114.

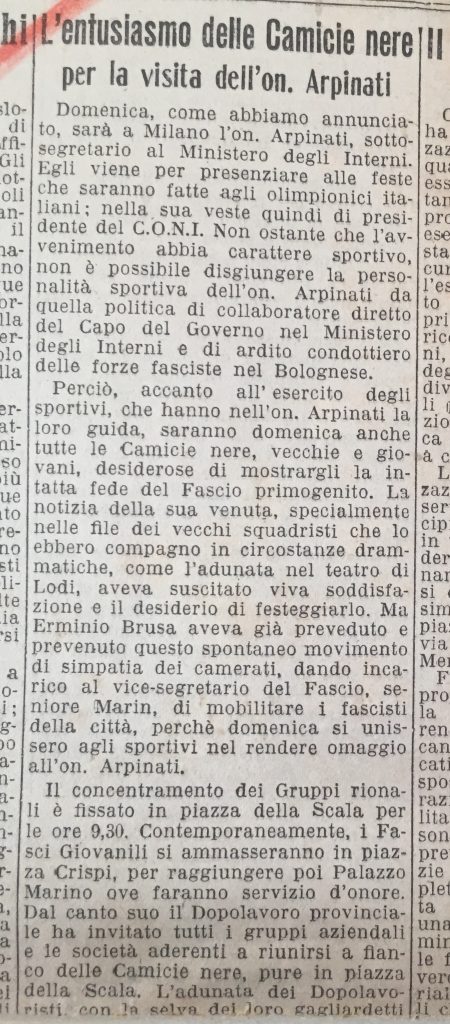

The main problem, for Arpinati, was to avoid this celebration of Italian Olympic winners turning into a very dangerous celebration of himself, by local fans. This risk was real, as demonstrated by a clipping (sent to the Prefetto) from an article published by a Milanese newspaper. The author writes about the scheduled coming of Arpinati to Milan as CONI President, adding:

‘Despite the sporting nature of this ceremony, it’s impossible to disjoin his sporting figure and his political figure, being Arpinati the direct collaborator to Mussolini at the Ministry of the Interior and brave chief of the Fascist fellows in Bologna. For this reason on this Sunday there will be not only the army of the sportsmen, who recognise Arpinati as their chief, but also all the Black Skirts, old and young, willing to show him their steadfast faith into the first-born Fascio’ (being the Fascist movement been founded in Milan in 1919).

-

In the second part of the article the author remembers the old times:

talking about the ‘gathering at the theatre, in Lodi’. In November 1919, Arpinati and some Fascist fellows were harshly contested at Teatro Gaffurio in Lodi by the local left-wing supporters lead by Ettore Archinti (see https://bit.ly/30YWk8i )

among which was 18-years old Giovanna Boccalini

Someone started to shoot and 3 people lose their lives. Historians claim that it was one of the first Fascist slaughters in Italy

Source: f. 1114.

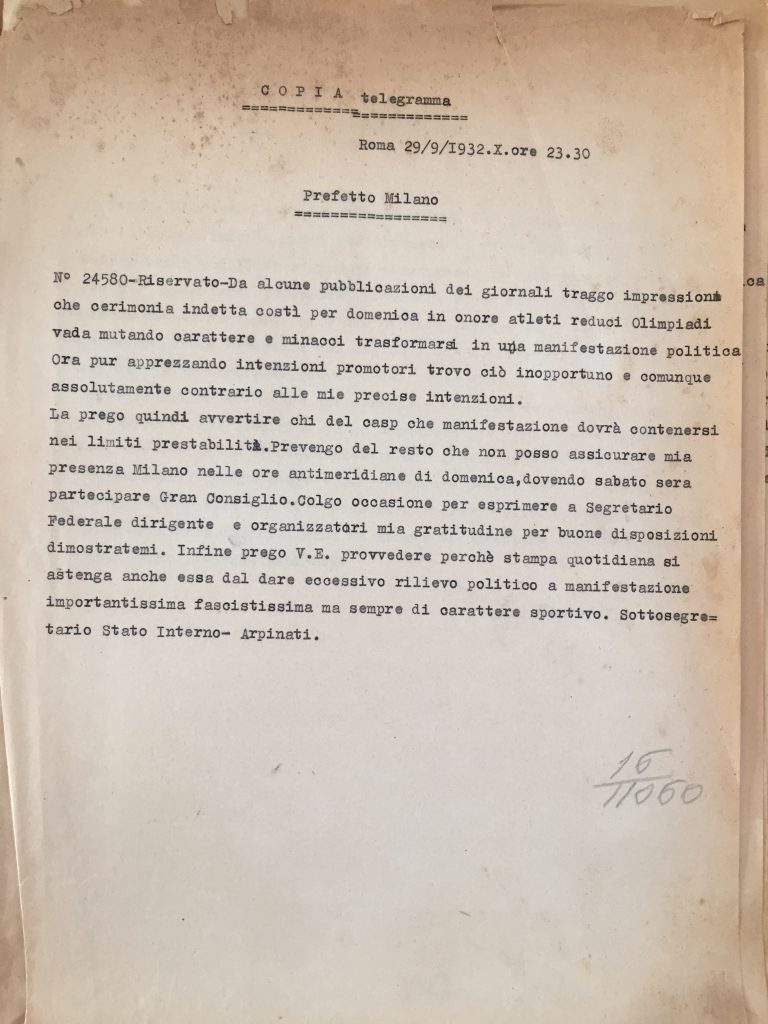

Arpinati was very concerned about such articles, as can be argued from a confident telegram sent to the Milan Prefetto on 29 September 1929. Arpinati writes that it seemed to him that for some journalists the Milanese sports ceremonies were turning into a political event.

‘Now, although I applaud the organizers’ good intentions, I found it inappropriate, and really contrary to my will’.

For this reason, Arpinati asks the Prefetto to tell them to keep it low-key and the local journalists not to add a political interpretation to a event ‘that is very Fascist, but just a sporting one’.

The copy of the confidential telegram sent by Arpinati to the Prefetto

Source: f. 1114

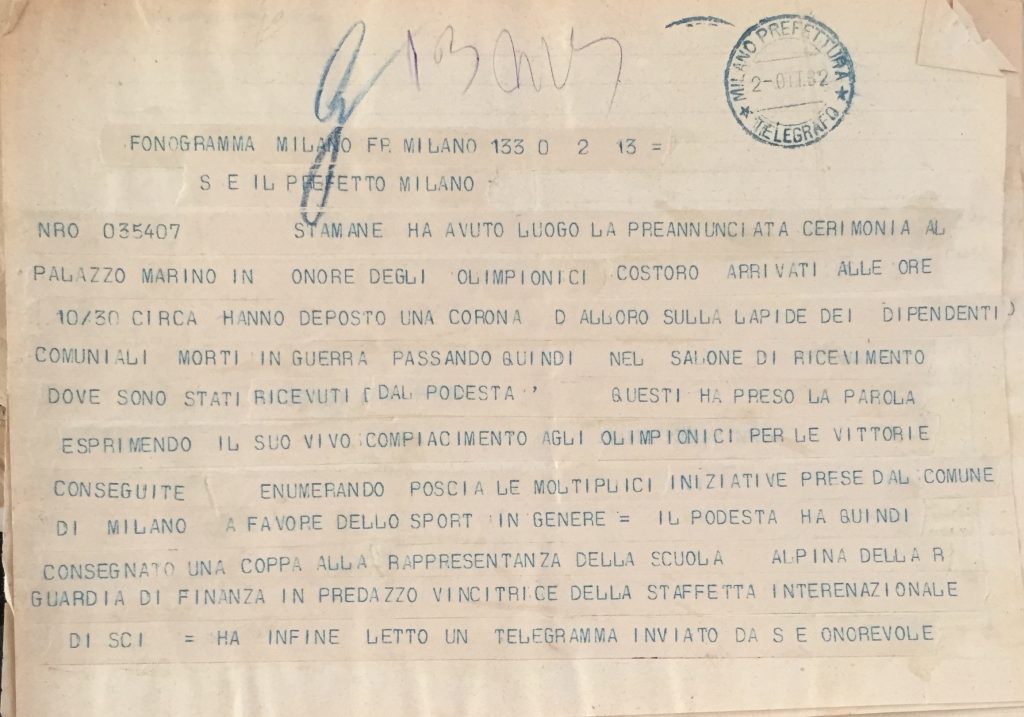

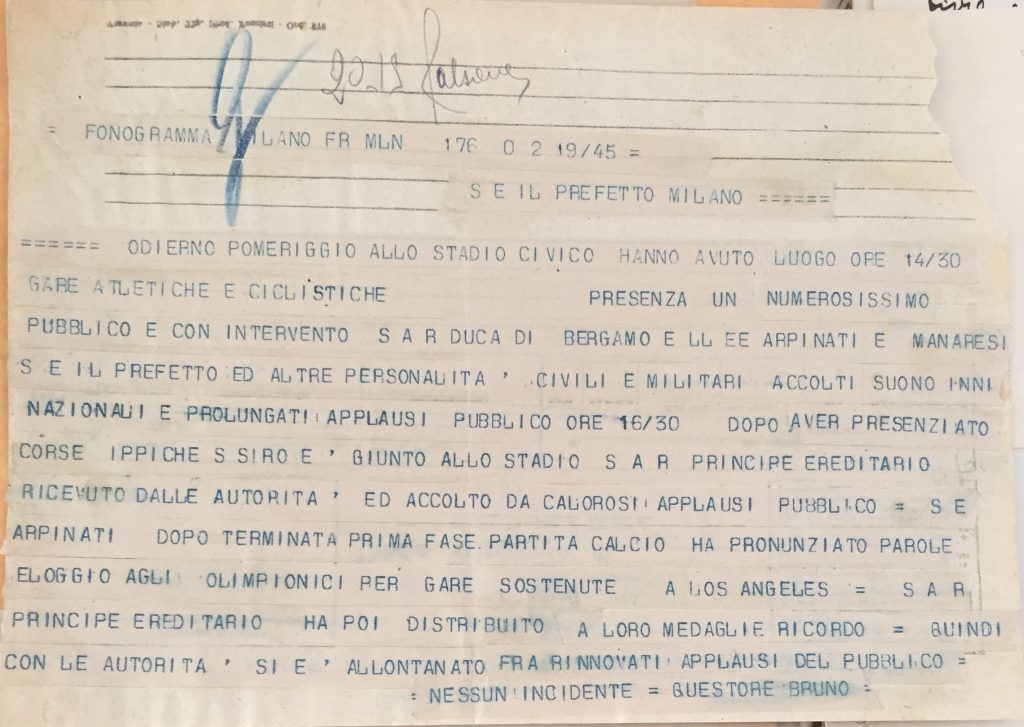

In the end, everything went well on Sunday 2nd October 1932. The day opened with the morning ceremony, held at Palazzo Marino, which Arpinati could not join in time and was late – the previous evening he attended a Gran Consiglio (the National Fascist Party executive board) meeting in Rome.

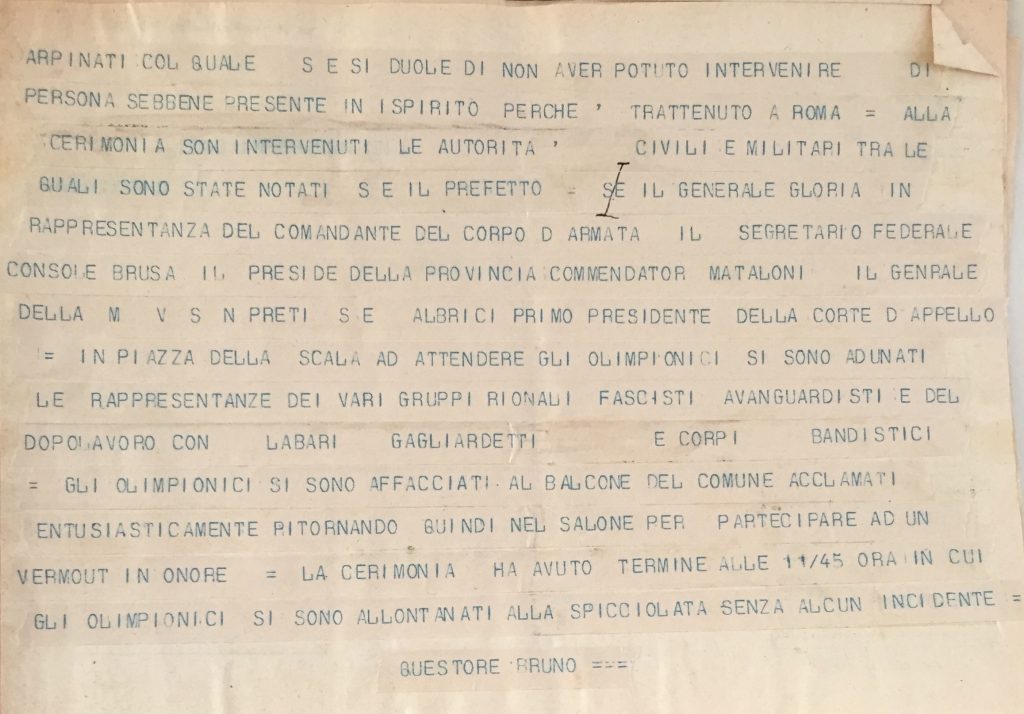

This phonogram about the morning ceremony was sent by Questore Bruno to the Prefetto. After the athletes laid a wreath for the Municipality of Milan employees fallen during World War I, the Mayor welcomed them. During his speech Visconti di Modrone recalled all that the Municipality had done to increase sport in Milan, then he read Arpinati’s telegram. In the audience, were a lot of members of the local associations and many authorities such as the Milan Federale, Erminio Brusa Source: f. 1114.

The Olympic athletes marching in Piazza della Scala

Source: Il Littoriale, 4 October 1932, p. 1.

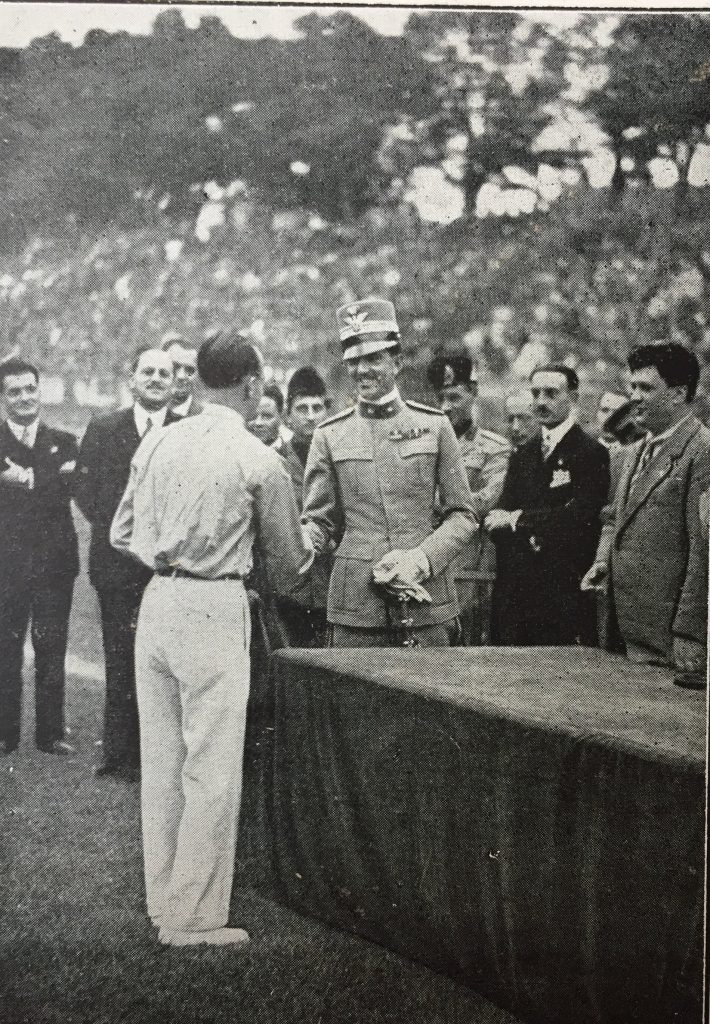

In the afternoon, Leandro Arpinati reached the Arena Civica, where he was joined by Prince Umberto, who had attended the horse racing at the San Siro Hippodrome. As witnessed by Questore Bruno’s phonogram, there were no problems, and during the halftime break in football match Arpinati made a speech; after which Prince Umberto presented medals to the Olympics winners.

Questore Bruno’s phonogram to the Prefetto

Source: f. 1114.

The Olympics winners marching in the Arena Civica athletics track. Note that there was no woman

Source: L’Illustrazione Italiana, 09/10/1932, p. 503.

Prince Umberto, holding one of the medals, captioned by what Arpinati is saying

Source: Il Littoriale, 4 October 1932, p. 1.

Arpinati giving his speech, in front of Principe di Piemonte and Duca di Bergamo

The athlete is the runner Beccali, winner of 1500m at the 1932 Summer Olympics

Source: Il Littoriale, 4 October 1932, p. 1.

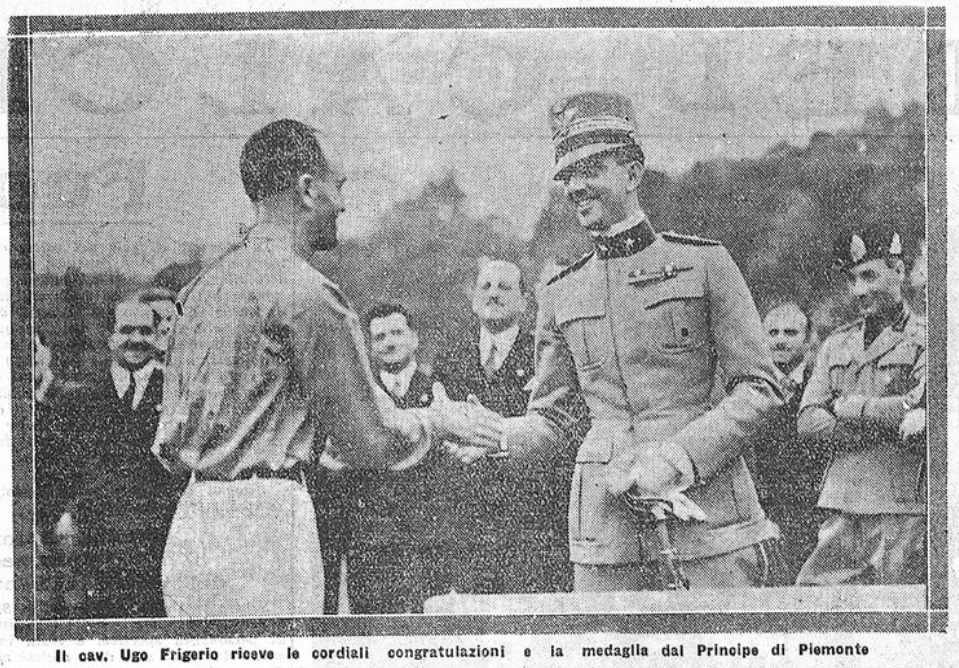

The Principe di Piemonte and Ugo Frigerio, a living legend of Italian athletics

although he won only bronze at 1932 Olympics (50km walk), he had previously won 3 gold medals, in 1920 Olympics (3km and 10km walk) and 1924 Olympics (10 km walk).

At the back, FC Inter President Fernando Pozzani (the man with moustache), can be seen smiling

Source: Il Littoriale, 4 October 1932, p. 3.

-

The Principe di Piemonte and Ugo Frigerio

Source: L’Illustrazione Italiana, 09/10/1932, p. 503.

-

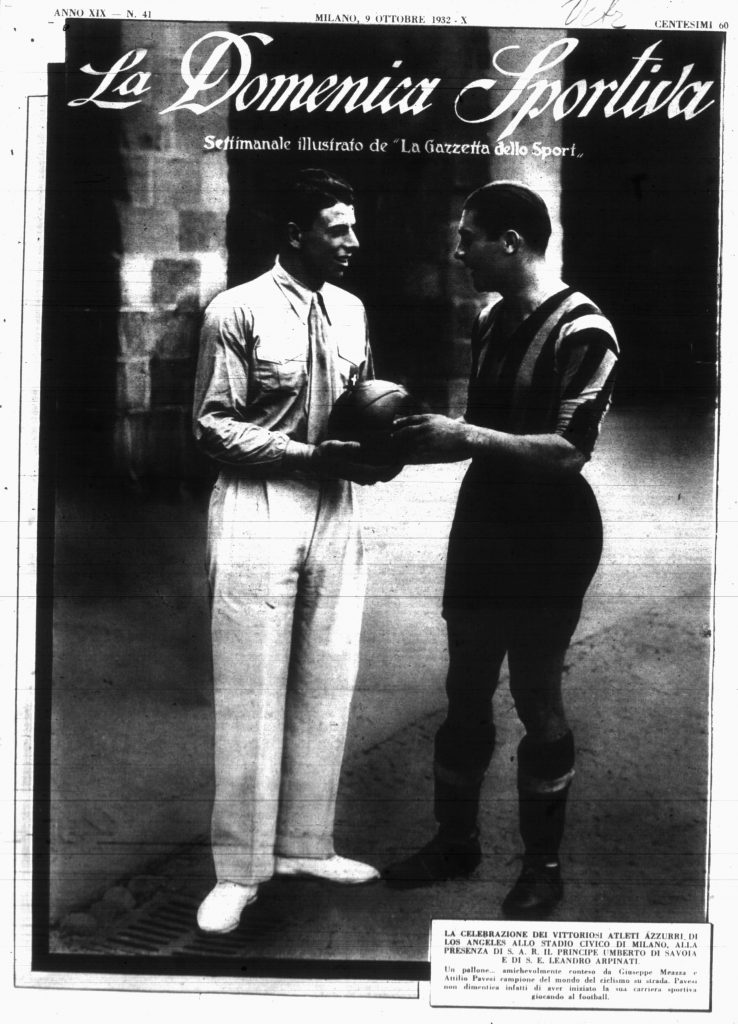

Double gold medallist in cycling Attilio Pavesi talking with FC Inter football star Giuseppe Meazza at the Arena Civica

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 09/10/1932, p. 1

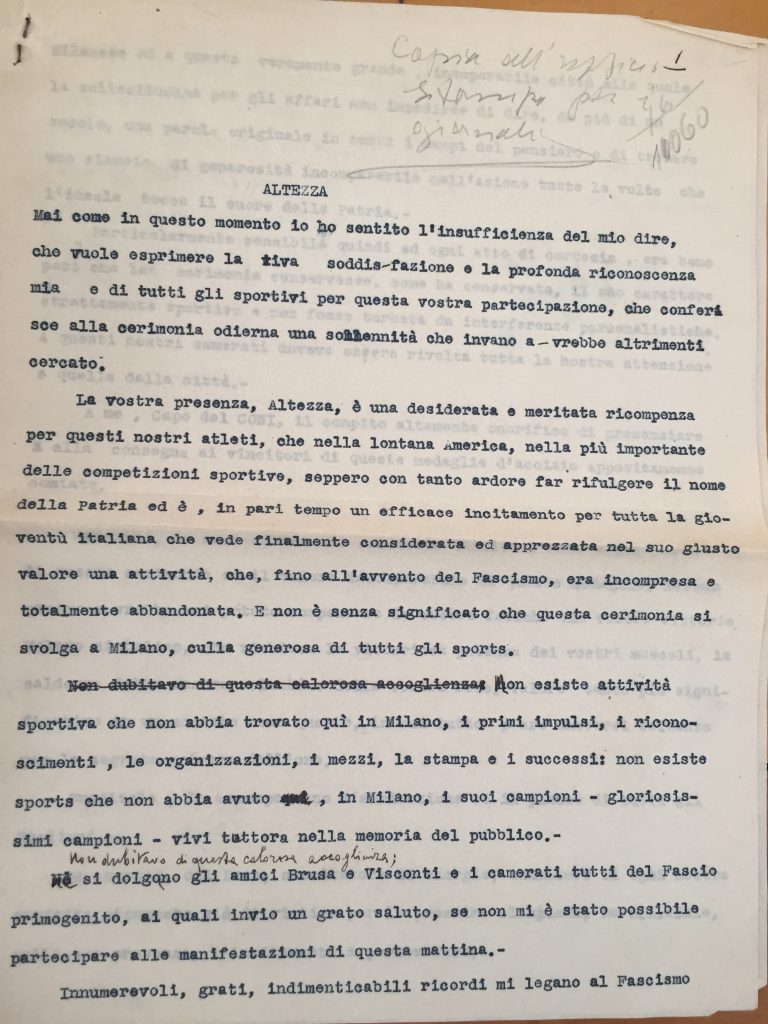

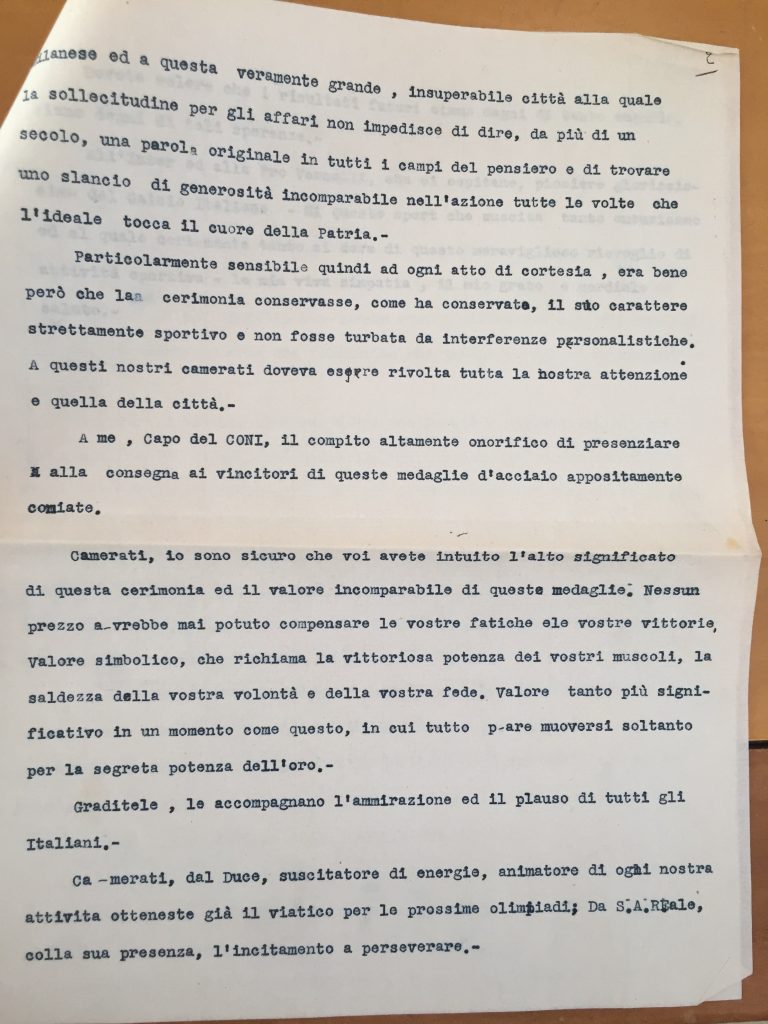

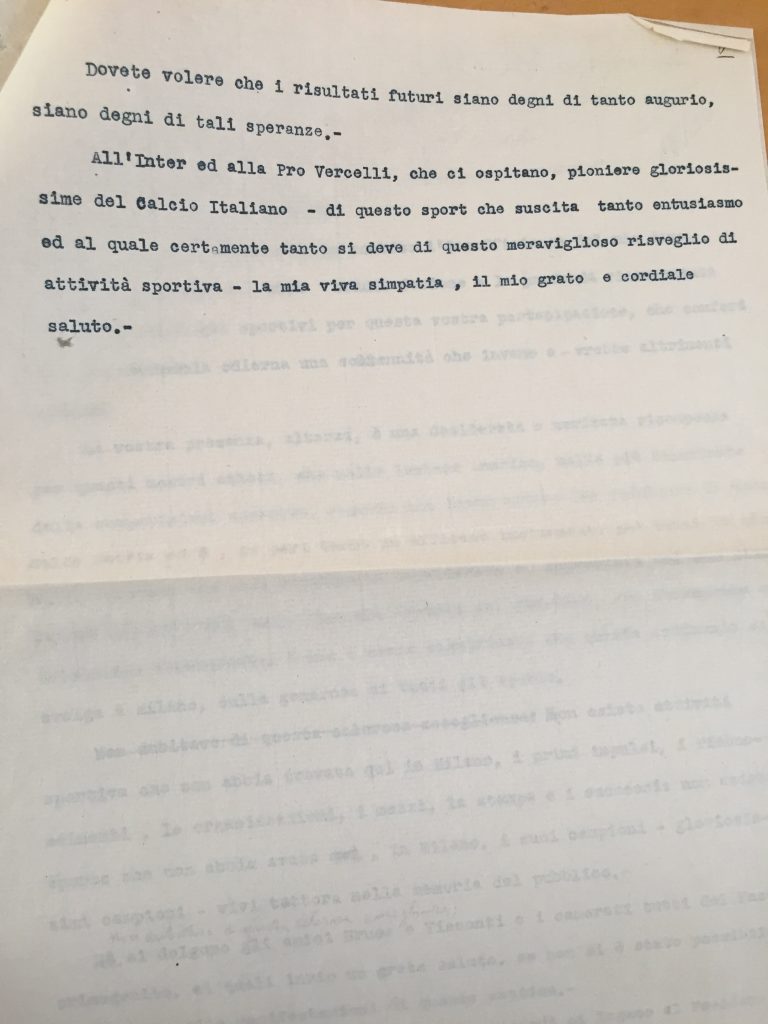

Among the Archivio di Stato papers there is a copy of Arpinati speech, in which he praises those who –

…in far America, in the most important of sporting events, were able to willingly glorify the name of their country, being so a good spur for all the Italian youth, which now can see sports adequately appreciated – before Fascism, sports was misunderstood and totally abandoned.

In the second part Arpinati recalls the sporting nature of the ceremony, that shouldn’t

….be upset by personalistic interferences, since the attention of everyone should be uniquely on these our fellows

to who Arpinati addressed the final part of his speech:

“Fellows, […] there’s no price for your labors and your victories”. The iron medals recalls “the winning power of you muscles, the firmness of your will and of your faith – such values in times like these, where everything seemed to work only by the hidden power of gold”.

The typewritten Arpinati’s speech, with manuscript corrections Source: f. 1114

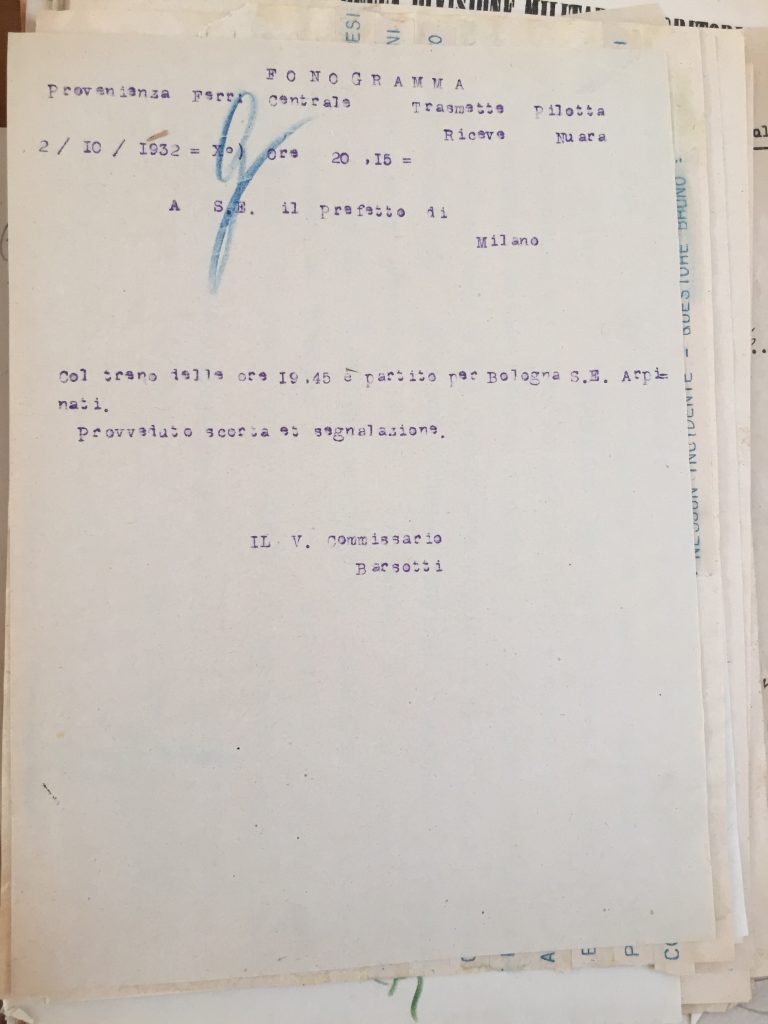

Even though Arpinati’s speech had concluded and of the football match had finished, the event still had not ended for some, the policemen who worked all day in the security service. Arpinati himself not only escorted but also monitored by the police during the entire time.

A phonogram in which Commissario Barsotti claims that Arpinati took the 7.45 PM train to Bologna

Source: f. 1114

Article © of Marco Giani

Read Part 2 HERE

Details of further reading: