The siege of Leningrad lasted for 872 days, from September 1941 to January 1944, killing about one million people and pushing the starving civilians to eat dead human bodies. With the Nazi troops making their biggest effort yet to win the battle, Josif Stalin commanded football games to be played among the ruins and the corpses. This was not just a matter of a leisure activity, a game, but a pugnacious message of resistance: Leningrad would never give up.

The use of sport for political or propaganda purposes was nothing new at the time, totalitarian states such as USSR, Nazi Germany or Fascist Italy resorted to it quite often, and perhaps not surprising that the communist dictator followed a very distant precedent.

In 1527, Spanish mercenaries and landsknechts from the army of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, carried out the Sack of Rome, which caused Pope Clement VII, born Giulio de’ Medici, to escape the city and take refuge in Castel Sant’Angelo. As the new regime arrived in Florence, Florentines got rid of Medici family and re-established a republic, which had been suppressed fifteen years before. With a quick and unexpected reverse in alliance, Charles V and Clement VII agreed to turn the imperial forces against Florence to return the Medici to power.

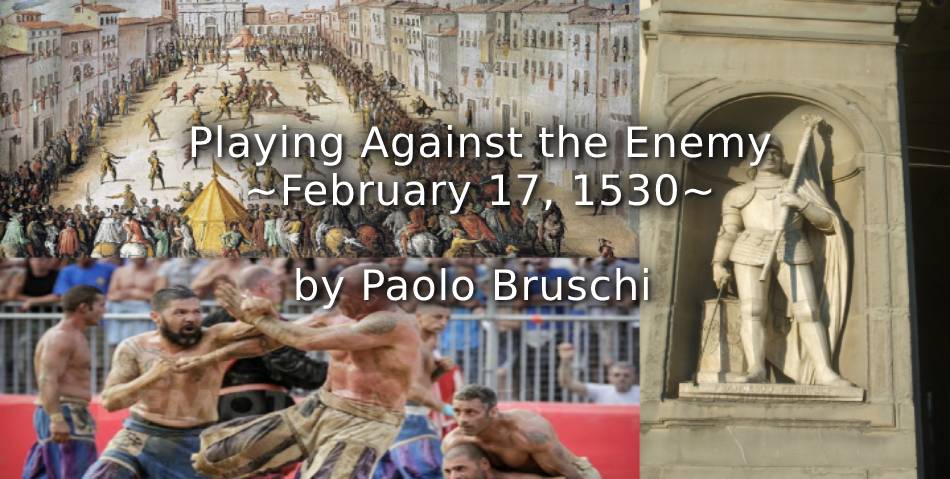

In the winter of 1530, Florence had been surrounded for several months and there was no way out. Although the wealth and trade that made the city a financial powerhouse in the Middle Ages had vanished and its citizens had run out of food supplies, the resistance spirit did not die down. Nearly 8,000 mercenaries and a popular militia of 5,000 men defended the “sweet liberty”, which was also protected by a new system of fortifications created by Michelangelo Buonarroti. The artist and architect, whose statue of David stands in front of the Palazzo Vecchio which was seriously damaged during the riots, which ended in the Medici overthrow, ordered town walls and bastions to be covered by mudbricks, not fired but air-dried, which were apparently artillery-proof. It seemed the city could not be conquered and the proud Florentines began to write on the walls “poor and free”. This was the popular sentiment at the beginning of Shrovetide and the Republic resolved to celebrate the festival as was the norm in peace time, organizing the usual game of calcio fiorentino or storico (“historical football”).

Calcio storico originated from ancient ball pastimes such as Greek sferomachia and Roman harpastum. Played in a sandpit, it was (and still is) a mix of modern rugby, football, wrestling and punching, involving physical features like speed, agility and strength. In other words, a ball game that people from all over the world experienced since the beginning of time as muted warfare.

The four quarters of the city – Santo Spirito, San Giovanni, Santa Maria Novella and Santa Croce, named for their great local churches – each formed a team of 27 men, whose aim was to get the ball over a 4-foot fence in other team’s end zone. To achieve this, players are allowed to use both hands and feet, as well as any other part of the body necessary, which often implies violence and brutality, such as choking and elbowing.

-

Calcio match in Piazza Santa Maria Novella in Florence.

Painting by Jan Van der Straet

On February the 17th, 490 years ago, preceded by trumpet fanfares and marching drums, the nine members of the Government left Palazzo Vecchio and headed to Santa Croce square, where the game was about to start and thousands of Florentines were waiting for the kick-off, unconcerned about cannonballs flying over the pitch. The first team wore white livery, representing the ideal of freedom, and the second wore green, as a symbol of the militia. Just to be sure the imperial army lined up on the hills in front of the square so they could see and hear what was happening, a group of musicians climbed the church of Santa Croce and stayed on the roof playing their instruments during the game. Many goals (cacce) were scored, but no reporter or historian have discovered the final result, or the team who won the white calf as the prize for victory. The real meaning of the game was clear to everybody: winners and losers were both associated in the same memorable act of courage and thus sending a defiant message to the enemy at the gates.

The following August, the Republic of Florence could no longer resist the famine, the diseases and the siege, and above all the death of its most valorous defender, Francesco Ferrucci. The captain, whose statue is now outside the Uffizi Gallery, led his soldiers in a desperate battle at Gavinana, on the Apenines. Against a much larger enemy, Florentines were almost completely slaughtered and Ferrucci himself was wounded and captured. According to well-regarded Renaissance historian and humanist Benedetto Varchi, and many others after him, imperial condottiere Fabrizio Maramaldo plunged his sword twice into Ferrucci’s throat, but failing to stop him from uttering his last and tragic words: ‘Coward, you murder a dead man’.

- Statue of Francesco Ferrucci outside the Uffizi, Florence

This glorious death gained Ferrucci eternal fame, especially due to risorgimental iconography and fascist celebration of his figure. On the contrary, Maramaldo came to signify infamy and vileness, even turning the name into a synonym of “villainous” and the verb maramaldeggiare as the act of somebody who torments a defenseless victim. Gianni Brera, the legendary sport writer, the model for many generations of journalists, popularized the word maramaldeggiare in his lyrical accounts on football and cycling, talking about a big team showing no mercy facing a helpless opponent or a sprinter who likes to humiliate his rivals on the finish line.

After Florence surrended, Medici returned to rule and thousands of “republicans” were banished and executed. However, the present calcio storico tournament, takes place every June on Saint John the Baptist day, the patron saint of Florence, and attracts hordes of tourists from all over the world, still commemorates the famous match that was played in 1530, which overcame the oblivion of centuries which still represents the pride and history of Florence.

Article © Paolo Bruschi