It is now 90 years since England Cricket Captain, Douglas Jardine, known by many as , ‘The Iron Duke’, controversially masterminded a 4-1 Ashes series win ‘down under’ in the infamous, ‘Bodyline Series’

The Bodyline tactic (also referred to as ‘fast leg theory bowling’) was an idea that Jardine came up with as way of preventing Australia’s leading batsman, Donald Bradman from dominating the series as he had done in 1930, where he had scored a massive 974 runs at an average of 139.

The controversial Bodyline Field

Jardine had become aware of the fact that during the first test at The Oval in 1930, Bradman had shown some signs of discomfort against the ball that bounced higher than normal at a fast pace and he believed that if he could exploit this potential ‘Achilles Heel’, he could prevent Bradman from winning the Ashes for The Australians in the 1932/33 series.

Prior to the tour he had met with England’s opening bowlers Harold Larwood and Bill Voce and explained his plan of bowling aggressively, targeting the batsman’s body rather than the stumps with short pitched deliveries often referred to as ‘Bouncers!’; batsmen in the 1930’s wore very little protection and with a packed leg-side field waiting for a catch, there was very little, thought Jardine, that even the great Don Bradman could do but get out of the way.

Douglas Jardine leading England out in the third test at Adelaide

The Bodyline tactic was deemed to be extremely brutal, unsportsmanlike and highlighted Jardine’s win at all cost attitude, as he explained on the eve of the first test,

I have not travelled thousands of miles to make friends. I am here to win the Ashes

David Frith, noted in Bodyline Autopsy, first published in 2002

As a leader, Jardine was in direct contrast to many of his predecessors. Unlike them, the main reason for being there was the cricket.

He would succeed, but at what cost?

Douglas Jardine was born in Bombay in 1900 and was educated at Winchester and New College, Oxford and would go on to play in 22 test matches for England , 15 as Captain. He was heavily influenced by C.B Fry on batting technique and replaced the great Jack Hobbs as an opening batsman for Surrey in 1921, when Hobbs was out of action.

Englands opening bowlers Harold Larwood and Bill Voce

He was first selected as England captain in 1931 for the series against New Zealand and was often a controversial figure and clashed with other members of the team, but despite this he kept the captaincy for the Ashes Tests in Australia in 1932/33.

Jardine had reputedly encountered the Australian in 1928 when Bradman had made his test debut and showed enough class to convince Jardine amongst others, that he was going to be one to one of the best players in the world and this made him determined to stop him if he could.

Of course he was proved right, but in contrast to his test career average of 99.4, Bradman finished the 1932/33 series with a batting average of 56.57 and Harold Larwood, who had only ever got him out once before, took his wicket six times in the five match series as a result of his leg-side short pitched bowling approach.

It worked as England comfortably won the series 4-1 , but Jardine insisted that he had only resorted to those tactics because he knew that Bradman would otherwise dominate England’s bowlers and saw the tactic as a means to an end.

The-Great-Don-Bradman

Interestingly, the MCC made changes to the law, almost immediately regarding the number of players allowed behind square, to only two and limited ‘bouncers’ to two per over in test matches, as a direct result of the Bodyline Series.

There was huge controversy over the series as it was not considered by many to be fair or to be in the spirit of the game and for a time it caused considerable ill feeling between the two countries involved prompting The MCC to state that;

Bodyline had breached the spirit of the game and while the tactics won the series, few people in the game were happy with how the Ashes had been regained

In Cricket and Empire first published in 1984, Sissons and Stoddart also noted that,

The Australians never devised a viable counter to the English onslaught and many suffered painful blows to the body and those injuries turned the Australian public against the visitors so that many ugly scenes of discontent, even hatred eventuated.

The cricket historian, Arunbha Sengupta believes that,

for all the negative press that ‘Bodyline’ and his many other altercations gave him, Jardine is remembered as one of the most brilliant England Captains and Jack Hobbs rated him second only to Percy Fender.

Sir Plum Warner probably paid him the ultimate tribute:

If ever there was a cricket match between England and The Rest of The World and the fate of England depended upon the result, I would want Douglas Jardine as Captain every time.

When Jardine retired from first –class cricket in 1934, citing his marriage to Irene Margaret Peat and work commitments as the major driving forces behind his decision, Wisden made no reference to it and many believe that he had been ostracised by the cricket fraternity, leaving him ‘isolated but impenitent’. (Sissons and Stoddart).

Douglas Jardine died of cancer in 1958 at the age of 57.

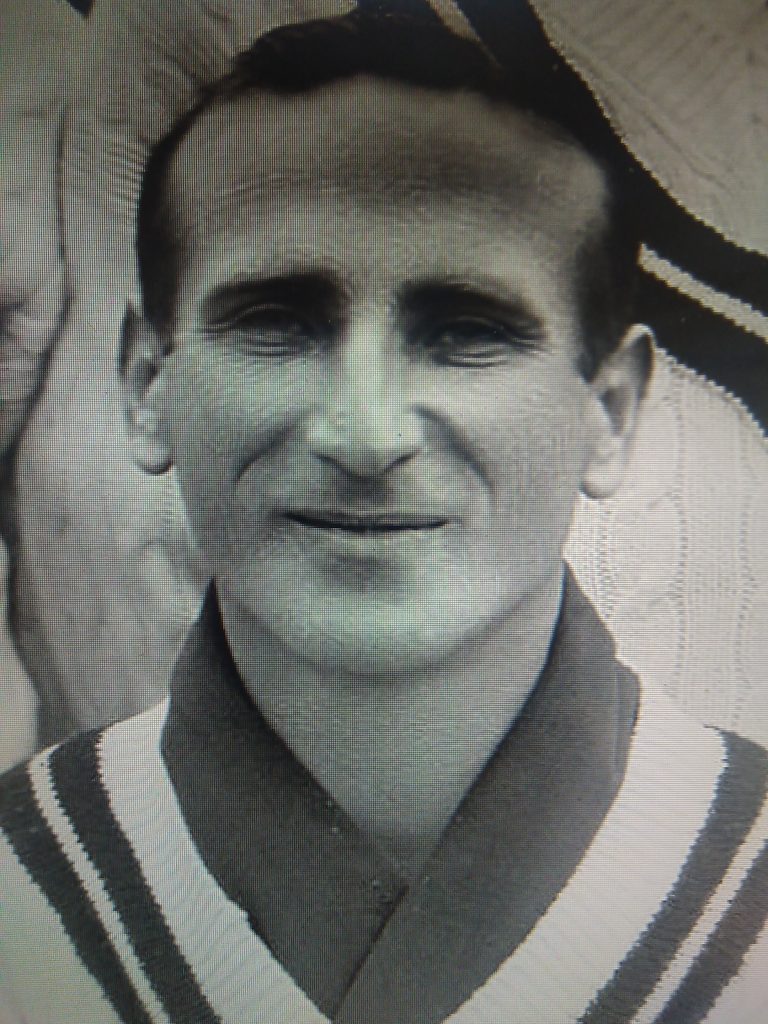

Douglas Jardine (1900-1958)

Article © of Bill Williams