Please cite this article as:

Zec, D. ‘White Eagles’, ‘Proud Albion’ and Spicy Garlic Food – The English National Football Team’s Visit to Yugoslavia in May 1939, In Piercey, N. and Oldfield, S.J. (ed), Sporting Cultures: Global Perspectives (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2019), 106-127.

ISBN paperback 978-1-910029-49-7

Chapter 6

______________________________________________________________

‘White Eagles’, ‘Proud Albion’ and Spicy Garlic Food – The English National Football Team’s Visit to Yugoslavia in May 1939

Dejan Zec

______________________________________________________________

Introduction

Looking back over the last one hundred years, as nearly a century has passed since the Yugoslav Football Association was established and a Yugoslav national football team played its first matches at the Antwerp Olympics of 1920, it is quite clear, to someone who is knowledgeable about the history of football in the Balkans, or is simply a football devotee and fan, that very few football matches played by the Yugoslav national team have lingered in national memory for so long, coloured fan folklore to such an extent and radiated with such exceptional glow as the match played between Yugoslavia and England in Belgrade in May 1939. This is remembered as a match between young and potent Yugoslavs, who were certainly talented but globally underestimated and unacknowledged, and an English team, seen as arrogant and cynical but universally recognized as simply the best in the world. The narrative about the match itself was, at the time, both epic and romantic, not just the narrative created by sports journalists and football fans, but the general public were also intoxicated by the game, with everybody expecting a duel of the titans, the Yugoslav ‘White Eagles’ and the ‘Proud Albion’.[1] Yugoslavs can certainly highlight romantic episodes from their footballing past – including an excellent performance at the first ever World Cup in Uruguay where they shared third place; an 8-4 victory over Brazil in 1934, the sensational beating of Nazi Germany in Vienna in 1940, in front of 60,000 spectators, and victories against strong teams of France, Czechoslovakia and Hungary.[2] Still, it is commonly accepted that victory over England in 1939 represents the highest achievement of Yugoslav interwar football, despite the fact that there were much more important competitive matches played in the 20 years between the First and Second World Wars.

Figure. 1 Captains Đorđe Vujadinović and Eddie Hapgood

The reasons why this match was so important and cherished by so many, both football enthusiasts and those who were unconcerned with the noble game, were both abundant and very diverse in nature. It wasn’t just the fact that the Yugoslav victory was seen as a proof that Yugoslavs were exceptional footballers and that the football played in the country was of the highest standard, it was also the fact that the victory was against the team that represented the nation which was perceived to have created and cradled the game, the keepers of the secret of how to play proper football, but also a team reluctant to share their knowledge and football wisdom to such extent that they did not want to participate in World Cups. In fact, it was the mythical admiration, which Yugoslav football fans and enthusiasts felt towards the distant and vague founders of the game that drove an almost insatiable and passionate desire to confront them. In addition, various political, social and economic circumstances made this match much more than a mere sporting event. Sport is never just sport, nor is a football match just a football match – political, ideological and diplomatic elements are almost always present.[3] The 1939 meeting between Yugoslavia and England certainly had political, economic, diplomatic, symbolic and cultural dimensions and was important for both nations, although perhaps not for same reasons. In the turbulent times, coloured by the rise of Nazism and the presentiment that a fragile peace might be in mortal danger, many people perceived one football match not just as a sporting event but also as an act of friendship between the two nations.[4]

This chapter represents an attempt to portray, as much as it is possible, all the fine levels and layers which made this football match one of the cornerstone events of Yugoslav interwar social history. Using various historical sources – archival documents, press reports, journal articles, memoirs, diaries, booklets and programmes, the chapter analyses the intertwined complexities behind one seemingly plain and simple event – a friendly football match between two countries – Yugoslavia and England. Detailed and careful discourse analysis of one football match and the narratives surrounding it can reveal a surprising amount of information about all sorts of things – both sporting and non-sporting in nature. An analysis of the match between Yugoslavia and England, played in 1939, shows the many difficulties of the Yugoslav political situation, both domestic and international. The struggles within the Yugoslav FA represent reflections of internal Yugoslav political and ideological confrontations and the effects of the match at the level of international politics and diplomacy show the difficulties of the Yugoslav international position in the turbulent years prior to the outbreak of the Second World War.

The main methodological deficiency of the chapter is that the story is rather one-sided. It is told from the Yugoslav perspective, not just because most of the sources and literature which were used are from Yugoslav and Serbian archives and libraries, largely for pragmatic reasons, but also because of conceptual necessity – a chapter has to be a product of confined ambition, no matter how interesting or complex the examined events or issues are. This, then, is predominantly a story of Yugoslav experience, a very complex experience indeed, but still a Yugoslav story about a historical football match that represented a milestone in Yugoslav sporting and social history and was also an important political, cultural and diplomatic event.

Yugoslav football in the interwar period

Before focusing on the events of the Yugoslavia – England match of 1939, it is important to place the match in an appropriate context. Contextualization demands paying attention to three particular issues of significance – 1) the history and state of Yugoslav football in 1939; 2) the state of global political and diplomatic affairs; 3) the internal political situation in Yugoslavia, which had strong links to the two previously mentioned issues.

Yugoslavia was a young sporting nation and at the time when the match against England took place, the Jugoslovenski nogometni savez (Yugoslav Football Association) had only existed for around 20 years. Informal footballing structures, of course, existed sometime before the First World War, but the Yugoslav FA was only founded in 1919 and the first national football championship was only staged in 1923.[5] Despite some sporadic contacts in the 1880s, football only came to the Balkans in the last decade of the nineteenth century, when it was introduced either by students or merchants who studied in or visited a number of big cities in Central Europe, such as Budapest, Vienna or Prague.[6] The first organizations, which could be identified as proper football clubs, were only founded in the early years of the twentieth century.[7] Thus, football in the Yugoslav lands was in its very beginnings of very low quality. Yugoslav footballers were amateurs in every sense of the word and the results of their first international attempts were disastrous. In 1920, Yugoslavia participated in the Olympic Games in Antwerp and lost both of the matches it played heavily – 7-0 to Czechoslovakia and 4-2 to Egypt.[8] However, things gradually improved; regular domestic competition saw several talented youngsters promoted to the national team and a number of skilful foreign players and coaches, mostly from Hungary, Austria and Czechoslovakia, joined Yugoslav football teams, leading to an improvement in the general technical and tactical state of the game. The first truly competitive generation of Yugoslav footballers on an international level emerged in the late 1920s, with the tremendous victory over the French national team in Paris in May 1929.[9]

The pinnacle of Yugoslav footballing success in the interwar period was reaching the semi-final of the first ever football World Cup, held in Uruguay in 1930. Yugoslavia managed to beat Brazil and Bolivia and progressed to the semi-finals, only to lose to the host-nation in a match that most of the reporters, both Yugoslav and international, labelled as very irregular.[10] Still, Yugoslav football enthusiasts were thrilled and saw the success in Uruguay as something upon which the national football team could build its dominance in Europe in the forthcoming years. However, this dominance never happened. Despite some outstanding performances during the 1930s, such as victories over Hungary, France, Czechoslovakia and an incredible 8-4 victory over Brazil in 1934, Yugoslavia failed to qualify for both 1934 and 1938 World Cups, constantly leaving the impression of a team that failed to meet expectations, not just the expectations of domestic football fans, but also the expectations of football experts throughout Europe. This sense of incompleteness and underachievement was certainly one of the factors why the Yugoslav football public had, for so long, wanted its national team to play against England, a side that was considered as the best football team in the world.

Apart from the fact that by the late 1930s there was a widely-accepted notion that Yugoslav national team was generally a team of under-achievers, another common perception about the state of the game in Yugoslavia was that from its beginnings and the first international match, played in 1920, to its last performances in 1941, just before the country was attacked and occupied by the Nazis, football was very heavily influenced by politics.[11] The intertwining between sport and politics was multidimensional – some sporting clubs were connected to particular powerful political individuals or political parties, or they were labelled as ‘class’ sporting clubs, either white or blue collar, especially in smaller cities and towns.[12] Left-wing sporting clubs were particularly numerous and active, and they were secretly connected and linked to the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, whose activates were otherwise labelled as illegal by the government.[13] However, the most important political differentiation in Yugoslav sport and Yugoslav football was the ethnic one, which confronted clubs and players of different ethnic origins, most notably Serbs and Croats.[14] Confrontations, which originated from a desire to keep control over the organization, financing and influence of sporting clubs and associations escalated by the end of 1920s, following the general worsening of the inter-ethnic situation in the country and the rise of nationalistic radicalism on one hand and state repression on the other. A number of prominent sportsmen and clubs aligned with mainstream political ideologies within their own ethnic corpora. This was particularly a characteristic for Croatian sporting and football clubs, which were linked with the organization Hrvatska športska sloga (Croatian Sports Unity), a sports wing of the very powerful and influential Hrvatska seljačka stranka, (Croatian Peasants’ Party), which practically represented a Croatian shadow government during 1930s.[15] This political differentiation and confrontation played an important role in the events surrounding the football match between Yugoslavia and England in 1939.

Yugoslavia and the United Kingdom – culture, geopolitics and diplomacy

Before shifting focus to the event itself, it is necessary to give a short overview of the circumstances that made this game much more than an ordinary football match. By the spring of 1939, Europe was in incredible turmoil, with everyone in fear and expectation of the spark that would ignite the flames of war and finally destroy the fragile system set-up in Versailles in 1919. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was in an especially precarious position – it was created in 1918, unifying all the southern Slavs in one state, but its creation meant that almost all of its neighbours, especially those who were on the losing side in the First World War, were deprived of the territories with a Slavic majority which they previously controlled.[16] The most dangerous of its neighbours and the main rival of Yugoslavia in the interwar period was Italy, which had aspirations towards the east coast of the Adriatic Sea, an area, which, to a great extent, belonged to Yugoslavia, but with significant enclaves of ethnic Italians, especially in larger towns on the Dalmatian coast.[17] Surrounded by enemies and revisionist countries, which desired to abolish the Versailles order and redraw the borders in the Balkans, Yugoslavia forged an alliance with Romania and Czechoslovakia, which was backed by France and, to some extent, by the United Kingdom. This alliance, called the ‘Petite Entente’, represented an important factor in central Europe until the mid-1930s.[18] However, because of the French policy to appease Italy, Yugoslavia gradually lost direct French support, which caused a major re-examination of the Yugoslav position in Europe. The economic crisis, which shook the world in 1929, was extremely devastating for Yugoslavia in the first half of the 1930s, with its entire agricultural sector in danger of collapsing.[19] As a direct result of the economic crisis, the structure of Yugoslav foreign trade shifted – Germany became the biggest importer of Yugoslav agricultural goods and raw materials while the share of trade between Yugoslavia and its former wartime allies, as well as their direct investments, was in steady and rapid decline.[20] Feeling abandoned and exposed to major German economic and political pressure, Yugoslavia was trying to balance between the two blocks. Still, despite the declining French political and economic support, the vast majority of the people in Yugoslavia felt they did not need to choose sides in the conflict that seemed inevitable – the sides had been chosen in 1914.[21]

This sense of old allegiance was reflected in all social interactions and perceptions. Before the First World War, Serbs and other Yugoslavs considered the United Kingdom as a distant and unknown country, whose global imperial goals often meant support to Serbia’s enemies, such as the Ottoman Empire.[22] However, the alliance forged in the Great War changed the perception completely. Cold, distant and calculated Britons were now seen as friends and comrades-in-arms, and various medical and humanitarian missions and actions, including help to the wounded and sick and care for orphaned Serbian children, forged mutual respect, friendship and sense of admiration.[23] The interwar period saw a huge breakthrough of British influence in Yugoslavia, both based on British ‘soft power’ and solid economic and political support. Masterpieces of British literature were translated into Serbian, exhibitions of British artists were organized, more and more people were interested to find out about British culture and the British way of life and an increasing number of people were interested in learning English. Naturally, one of the most striking features of the British way of life, at least to an average Yugoslav, was the British love for sports and football in particular. On the eve of the Second World War, those Yugoslavs who opposed Nazism, and that was the overwhelming majority of the population, looked upon Britain as an inspiration and an ally. In addition, as confrontation seemed increasingly likely, the British understood the necessity to intensify the propaganda efforts in both friendly and neutral countries. This was also quite evident in the case of Yugoslavia. British propaganda in Yugoslavia intensified through the actions of the British Council, British-owned ‘Radio Belgrade’ and through other outlets controlled by the British.[24] A football match between the two nations, coming in such delicate times, was seen as a perfect opportunity to re-affirm the friendship between the two countries and to promote feelings of mutual respect and admiration, which had been strong since the years of joint struggle in the Great War.

Arranging the match

Yugoslav football officials had been trying for a very long time to arrange a friendly football match between the two sides. In fact, president of the Yugoslav Football Association Mihailo Andrejević told the press in 1939 that ‘this match was our wish from the day we founded our association’.[25] The admiration Yugoslav football enthusiasts had for British players and coaches was tremendous and the general interest in results and descriptions of the matches played in England and Scotland was huge. The Yugoslav sporting press always designated space for results and match reviews, sometimes simply taken and translated from various British newspapers, but sometimes written by special reporters who had the rare opportunity to see matches in person.[26]

However, the strong desire of the Yugoslav public to host the English footballers only became a real possibility in 1939. Before then, football matches played between Yugoslav and British teams were rare and sporadic – ‘Liverpool’ and ‘Chelsea’ visited Yugoslavia in the mid-1930s and played several friendly matches against local teams and ‘Građanski’ from Zagreb and ‘BSK’ from Belgrade, the strongest and most prominent Yugoslav clubs of the time, visited England and Scotland, competing against several teams but failing to win a single game.[27] Reading the memoirs of Yugoslav footballers and football officials of the time, there is a hint that the match between the two national teams had never happened prior to 1939 mainly because the English FA asked for substantial financial compensation in order to travel abroad and visit Yugoslavia, and Yugoslavs were not able to cover the costs.[28] However, the breakthrough happened in 1938 when Andrejević was invited as a guest of honour to participate in the celebration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the FA and to attend the match between the representative teams of England and the Rest of Europe, played in October 1938 at Highbury. During this occasion, he discussed the issue of a possible friendly match with William Pickford, President of the FA, and apparently the initial arrangement had been agreed, although no details were revealed at that time.[29] No firm dates were set and no financial compensation was disclosed.

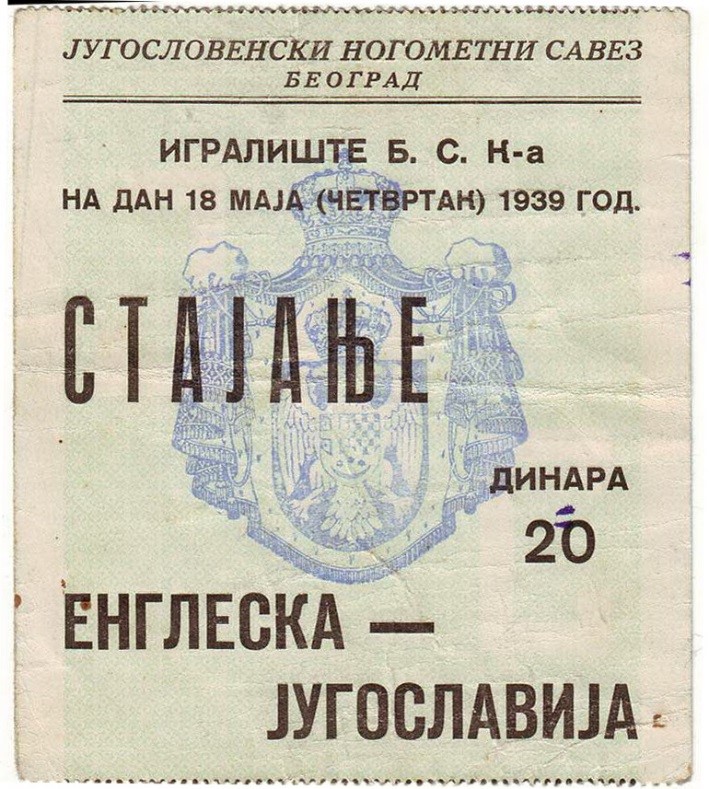

Some researchers suggest that the change of mind from the English football officials had a lot to do with the fact that British governmental officials, especially from the Foreign Office, encouraged sporting exchanges with nations like Yugoslavia, especially in the late 1930s, as Foreign Office experts and politicians realized that friendly football matches could have a positive impact on British national interests.[30] Sporting propaganda was regarded as a very powerful tool for promoting British soft power in the world. Still, financial arrangements had to be sound. The Yugoslav Football Association managed to get financial backing from the Yugoslav government and the Ministry of Physical Education actually provided a grant to the Yugoslav Football Association, because of the tremendous sporting, cultural and political significance the match between the two nations would have and because the match would be the main event of the Yugoslav FA’s twentieth anniversary celebrations.[31] The arrangement was that the Yugoslav FA would have to pay a guaranteed sum of £1,000 (about 240,000 Dinars) to the English FA as compensation for their appearance, irrespective of income from the gate, and that any surplus would be divided equally between the two associations, after covering other costs, such as accommodation, advertising and pitch preparation.[32] In the end, the gate income was much higher than predicted and everybody gained financially – the total income was about 700,000 Yugoslav Dinars, which meant that both teams made about 300,000 Dinars (£1,250) profit.[33] Finally, after arranging financial details, the English tour to Italy, Yugoslavia and Romania was officially announced in early March and the match between Yugoslav and English national teams was scheduled for May 18, 1939.[34]

Figure 2. A ticket from the Yugoslavia-England Match, 1939

Before the game

Similarly to the English national team, the Yugoslav FA also arranged to play three games in a very short period of time, in May 1939. The Yugoslavs were supposed to travel to Bucharest to face Romania, to host England in Belgrade and, finally, to accommodate Italy at a venue that by March 1939 had still not been decided.[35] All these matches were supposed to be a part of the national celebration of 20 years of organized football in the country, and, of course, with both official and unofficial world champions visiting, it was certainly the biggest and most important footballing event ever staged in Yugoslavia. The significance of it was underlined by a rather unusual event, which was staged on the evening of May 3, when Đuro Čejović, Minister of Physical Education, spoke on national radio about the forthcoming football matches. In his speech, which was rather an unprecedented event, because politicians used to speak on the radio only regarding important issues and very rarely about sporting events, the Minister said that he was sure that ‘our sportsmen, conscious of the difficult task ahead of them, will give their best to defend the reputation and honour of both Yugoslav sport and the state’.[36] The political dimension of the event was amplified when Čejović stated that ‘our people is talented at sport, our people is unselfish, its character is chivalrous and it is worthy to fight and win’, which is a clear reference to historical experience of Serbian people and its hardships during the First World War, when they were willing to confront the opponent which was much stronger and win in the end.[37]

However, despite its importance, pressure from the state officials and huge public interest, the whole affair started on the wrong foot and ultimately encountered various difficulties. The first major problem was the fact that Yugoslav team performed terribly in the first match in Bucharest, losing to Romania 1-0.[38] Romania was by no means a weak opponent and competing against them was no easy task, especially when playing away, but it was not the result which caused concern, but the performance, which was described as simply appalling by the reporters and Yugoslav fans. In fact, one newspaper wrote that one Yugoslav, who had lived in Bucharest for a long time and had attended the match, told their reporter that he had never felt more ashamed of being from Yugoslavia.[39] This was, clearly, a dramatic overstatement and one which was very characteristic of the Yugoslav press, but the general impression amongst the public was that the national team had performed poorly and that the players were not giving their best on the pitch. With the Yugoslav team set to face both the official and unofficial world champions a few days later, the performance and attitude of the Yugoslav players was a cause of huge concern.

This poor performance was a prelude to a much bigger problem, which fully emerged only a few days before the arranged match against England and its roots were political in nature. As mentioned before, the history of Yugoslav football in the interwar period was heavily influenced by internal Yugoslav political struggles. Footballers and football clubs from different parts of the country, most notably from Croatia, often actively participated in political manifestations and linked themselves with Croatian nationalist organizations, supporting the idea of the decentralization and federalization of the country. Every so often, Croatian sportsmen were engaged in an active boycott of the Yugoslav national team and nationwide competitions, in order to put pressure on state authorities to accept some of their political demands. Even the biggest Yugoslav sporting success of the period, the 1930 football World Cup campaign, was achieved without the help of players from Croatia.[40] A few days after the match against Romania, which saw players from all over Yugoslavia participating in the national team, including prominent Croatian footballers from clubs such as ‘Građanski’, ‘HAŠK’ and ‘Hajduk’ Split, the Zagreb Football Sub-association, as the representative of Croatian football clubs, presented an ultimatum to the Yugoslav FA.[41] Knowing how important match against the English was, and implying that Croatian players might not take part in it if their demands were not met, they asked for two things. First, they wanted to host the Italian team somewhere in Croatia, in Zagreb or Split, and to keep all the income from the match. Secondly, and of greater political importance, they proposed a complete reorganization of the Yugoslav Football Association, whereby the Yugoslav association would effectively become a confederation of ethnic football associations, with each of these ethnically-organised associations recognised by FIFA and with the capacity to arrange international matches.[42] The first demand was actually plausible, although probably not advisable at the time, as the Italians had territorial aspirations over Croatian lands, a political confrontation which had the potential to turn a football match into riots and a violent affair, but the second demand was completely unacceptable for the Yugoslav football officials. Even if the Yugoslav FA decided to accept its practical dissolution, the government and the state authorities would have rejected it, as the federative (in this case, even confederative) principle, either in politics or any other sphere of social organization, was perceived by the authorities as subversive and hostile towards Yugoslav national unity. Therefore, the Yugoslav FA decided to reject the demands and stated that clubs which pressured their players not to join the national team would be punished with suspension from the association.[43] Neither side succumbed and several Croatian players left the national team, leaving the team management with a terrible problem; six players had to be replaced at the last moment.[44] The team manager Boško Simonović was furious and offered his resignation but the Yugoslav FA rejected it. The team that was supposed to face the English was still good, but it was generally accepted by the Yugoslav public that the opportunity to avoid defeat had now completely gone.

The English delegation arrived in Belgrade on of May 16, after a good performance and a 2-2 draw against Italy in Milan in a match that was considered by many as the ‘match of the century’.[45] The English tourists disembarked at the Belgrade central train station in the afternoon hours to be warmly greeted by a cheering crowd.[46] The Yugoslav football officials asked the people to meet the English players at the train station and cheering group of football fans waiting for the English was huge and very enthusiastic. About one thousand football fans, mostly boys and teenagers, were saluting the guests from England and asking for the players’ autographs.[47] The President of the Yugoslav FA, Andrejević, formally welcomed the English delegation, led by Stanley Rous and Tom Whittaker, with the words that he had ‘the honour to welcome the greatest opponent ever, from whom our footballers will have the opportunity to learn a lot’.[48] The English were staying in the best and most luxurious hotel in Belgrade, ‘Srpski kralj’ (‘The King of Serbia’) and everything about their stay was prearranged, including the training sessions, official meetings and even the small things, such as food preparation. On the day before the match, the English players visited the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier near Belgrade and paid their respects to the fallen soldiers of the Great War. They also visited Oplenac, the residence of the Yugoslav Royal Family, where they visited the grave of killed King Aleksandar I Karađorđević.[49] At the end of the day, the Yugoslav FA and Ministry of Physical Education organized a banquet in honour of the guests, and the Minister himself greeted the English footballers, saying that welcoming them was the highest honour that he had ever had during his entire career.[50]

Figure 3. A commemorative postcode of the game with English players

The day of the match

On the day of the match, a beautiful warm and sunny day, almost ideal for a game of football, thousands of people gathered around the stadium hours before the kick-off, with many enthusiasts trying to get hold of tickets. Approximately 25,000 match tickets had been sold by the Yugoslav FA in the days before the match and the maximum capacity of the ‘BSK’ stadium was around 30,000.[51] However, we do not know precisely how many people attended the match because, apart from the tickets sold, many tickets were given away by the Yugoslav FA to sponsors, sporting and political officials, various diplomats and other interested parties. In addition, many counterfeited tickets appeared on the black market, especially in the melee that was created in front of the stadium a few hours before the kick-off and some of the people with faulty tickets did manage to get in. Others tried to bribe the stewards to get in. Some reporters suggest that there might have been around 40,000 spectators at the match, which would make it the highest attended football match in Yugoslav history before 1945.[52] Football fans came to the match from all over the country, some even from other countries. About 200 football fans came from Bulgaria via special train just to see the English footballers.[53] For those who were not lucky enough to get hold of the tickets, local authorities throughout Yugoslavia installed huge loudspeakers for them to listen to the wireless broadcast.[54] These loudspeakers were tested a few days before the match, when the Yugoslav Broadcasting Company transmitted a live broadcast of the match between Italy and England, played in Milan.

The announced squads were – for England: Woodley, Male, Hapgood, Willingham, Cullis, Mercer, Matthews, Hall, Lawton, Goulden and Broome.[55] For Yugoslavia: Lovrić, Požega, Dubac, Manola, Dragičević, Lechner, Glišović, Vujadinović, Petrović, Matošić and Perlić.[56] Yugoslav journalists agreed that the English team was probably the best that could be assembled at that moment.[57] On the other hand, it was felt that the Yugoslavs would miss their Croatian superstars. Most positions were satisfactorily covered, but the position of goalkeeper was critical. Instead of Franjo Glaser, legendary keeper of ‘Građanski’ Zagreb, a young and inexperienced 18-year old debutant Ljubomir Lovrić from ‘SK Jugoslavija’ was chosen to stop the English attacks. In a twist of fate, the young debutant Lovrić would play the match of his career against the English.[58]

Figure 4. Yugoslav and English teams line up before the match

Reports from the match suggest that the tempo of the game was quite high and that Yugoslav footballers, surprisingly, started very offensively and aggressively and attacked rapidly, especially down the flanks. The English apparently did not expect this and their start to the match was marked by confusion.[59] Initial aggressiveness paid off and the Yugoslavs took an early lead, with Svetislav Glišović scoring in the fifteenth minute. After they had conceded a goal, the English managed to pull themselves together and attempted to equalize, creating several good scoring chances. The tempo was still very high but now both teams were creating serious scoring opportunities. However, it was apparently a day of glory for the young debutant goalkeeper Lovrić, who managed to thwart all English attempts to score. The half-time score stood at 1-0 to Yugoslavia. The second half started in completely the opposite fashion to the first. England were aggressive and dangerous and the Yugoslavs were confused. In the forty-ninth minute, Frank Broome managed to score, exploiting the mistake of the Yugoslav centre-half Petar Manola. At this moment, the game was entirely in English hands. They continued to press on and it seemed that a second goal was only a matter of time. However, young Lovrić saved the Yugoslavs from conceding. Then, all of a sudden, when nobody expected it, the Yugoslavs managed to organize a quick counter-attack. A long ball reached left-winger Perlić, who collided with fullback Male, but quickly managed to get up and sprint towards the goal unmarked. He was left one-on-one with Woodley and managed to score. The English continued to press on for an equalizer and the Yugoslavs continued to defend, with occasional dangerous counter-attacks. Both teams had their chances before the end of the match, but the result did not change and the Yugoslavs won 2-1.[60]

Figure 5. Ljubomir Lovrić catching the ball

The Yugoslav public was obviously thrilled with the win. Everything else was forgotten. Even the fact that Yugoslavs were about to face World Champions Italy in few days’ time (a match they would lose) did not matter much, as they were able to do what the official world champions were not – to beat the English. 1939, as a whole, was terrible for Yugoslav football, with the victory over the English the only one achieved in six matches played, but at that moment statistics were not important. The ethos of the victory over the best team in the world was so overwhelming that many people saw it as an illustration of the national character. One newspaper article stated that ‘the achievement of our national team represents, both for us and for the entire world, another proof of the capability of our people to compete as equals and a worthy adversary to anyone, in any cultural or sporting competition, even if we don’t enjoy the same opportunities in life’.[61] On the other hand, the English perception of the game was much more down to earth. The British press acknowledged that the Yugoslav victory was well-deserved, although certain circumstances which disadvantaged the English team were noted – the hot day, hard pitch, inconsistent referee and the fact that Hapgood suffered a slight knock during first half, which prevented him expressing his skills and full potential.[62] However, there were no complaints over the result, which was seen as the result of the greater desire of the Yugoslav players to achieve a positive result.[63] It was obviously very pleasant for Yugoslav ears to listen to praise coming from British football experts, for example that the ‘Yugoslavs engaged into battle with enormous national uplift and managed to achieve the pinnacle of their skill, like they never did before, thus managing to beat us 2-1’.[64]

The aftermath

Focusing on a different dimension of the game, both diplomatic and political circles in the United Kingdom were very pleased with the match. The fact that the Yugoslav Prime Minister attended the game, along with many distinguished ministers and other dignitaries spoke volumes of its political importance and potential to facilitate diplomatic influence.[65] One British diplomatic correspondent, comparing the matches in which Yugoslavia hosted England and Italy, wrote that, in the second match, Italian players were booed off the field at the end of the game, the Italian flag was torn up by the crowd, the team’s bus was stoned and vandalised and that Yugoslav ministers made derogatory comments about the Italian team, their style of play and the moral characteristics of their players, while the English minister in Belgrade had received demonstrative ovations from the crowd a fortnight earlier and Yugoslav ministers had praised the gentlemanly conduct of English players on the pitch.[66] Of course, it is not surprising that the Yugoslav football crowd would be abusive towards Italians, given the history of the two countries and the tensions between them in the interwar period, but the conduct of Yugoslav political officials, who clearly expressed their sympathies for the English, despite the official policy to remain neutral, was something that would certainly cheer the diplomats in the Foreign Office.

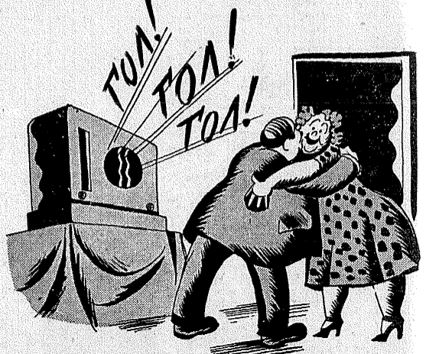

The only dark spot on the event was the result of Yugoslav oversensitivity and of the fact that Yugoslavs were not accustomed to the British sense of humour. A Few days after the match, Yugoslav papers reported that John Macadam, a Daily Express journalist, wrote that the English team had lost because the footballers were starving for their entire stay in Yugoslavia. Apparently, according to him, Yugoslav cuisine was not only so heavily dependent on garlic to the point that the English couldn’t eat the food, but even the cooking pots and pans were infused by garlic essences to such an extent that they couldn’t be used for preparing garlic-free food.[67] The level to which the Yugoslav public was insulted by this obvious joke was ridiculous from today’s perspective. The main chef of the ‘King of Serbia’ hotel was interviewed and he was forced to provide the entire menu of the English team to the readers, just so everybody could be sure that there was no garlic used during food preparation.[68] The Daily Express reporter was publicly discredited by the Yugoslav press, which published that he spent around 180 Dinars on food in the hotel per day, which meant that he ate for three regular people. Reports concluded that he either did not mind the garlic that much or that garlic was in fact not used.[69] Primarily, the ludicrous response of the Yugoslav public to a bad joke showed how important this victory was for the nation. Yugoslavs would not allow anything to overshadow the great victory, especially not something that amounted to an accusation of starving and almost poisoning the guests, which portrayed the hosts not just as a nation who did not care about fair play, but also as a nation of savages with no sense of civilized behaviour.

Figure 6. ‘Goal, goal, goal!’ An illustration from Yugoslav newspapers.

Conclusion

By the mid-1930s, Yugoslav society had become fully accustomed to the game of football and, in many ways, it became a true national pastime. The excellent performance by the national team in the 1930 World Cup in Uruguay, the competitiveness of the Yugoslav clubs in regional tournaments, such as the Mitropa Cup, and the fact that there were several talented Yugoslav footballers playing for prominent French, Austrian and Swiss clubs, earned Yugoslavia a growing reputation in European football. However, the failure to qualify for 1934 and 1938 World Cups, unexpected defeats in several friendly matches against much weaker opponents during the late 1930s, as well as internal conflicts over power and influence within the Yugoslav FA, gave the impression that Yugoslav football was in deep crisis. Beating a formidable international football side was seen as an opportunity to emerge from the crisis and the opportunity presented itself in spring of 1939, when it was confirmed that England would play against Yugoslavia in Belgrade. The match would be both the 100th official match of the Yugoslav national football team and the highlight of the twentieth anniversary celebration of the Yugoslav Football Association.[70]Conclusion

The excitement over the match in the Yugoslav public was overwhelming – it was a long-lasting desire of Yugoslav football enthusiasts for its national side to compete against the team which was considered the best in the world. The match itself, which ended in Yugoslav victory, was widely considered as one of the most important national sporting successes in the period prior to Second World War, and the state of euphoria and jubilation long after the match showed how important football was to Yugoslav people. This international football match was not a one-dimensional event, limited to its sporting side, but also reflected greatly on various social, cultural and political issues regarding the two nations and their historical and contemporary relationship. The match between Yugoslavia and England ultimately showed three things. Firstly, that Yugoslavs desperately desired their football team to be internationally recognized and they hoped that a victory, or even a decent opposition, would draw international acclaim. A good performance and good result were seen as a confirmation that the game was on the right path and that, despite all the political turbulence, the future of football in Yugoslavia was bright. Secondly, the match itself, especially when compared to the match between Yugoslavia and Italy, shows that Yugoslavia and Britain were closely aligned politically at a time when global confrontation seemed increasingly more likely, even if the Yugoslav government wanted to remain neutral and out of conflict. Thirdly and finally, the match proved that sport, football in particular, had tremendous potential for political and diplomatic action and that very often acting through ‘soft power’ is the best possible way to affect and shape public opinion.

References

[1] The term ‘White Eagles’ was a popular nickname for the Yugoslav national football team in the interwar period, often used by the press, which originated from the heraldic characteristics of the Yugoslav coat of arms. Similarly, the Yugoslav sports press very often used the nickname ‘Proud Albion’ when it wrote about the English national football team. This still continues today.

[2] Boško Stanišić, Plavi, Plavi! 1919-1969 [The Blues! 1919-1969] (Belgrade: Borba, 1969), 67-121.

[3] Stuart Murray and Geoffrey Allen Pigman, ‘Mapping the Relationship between International Sport and Diplomacy’, Sport in Society 17, no. 9 (2014): 1098-1099; Peter Beck, ‘The Most Effective Means of Communication in the Modern World?: British Sport and National Prestige’, in Sport and International Relations: An Emerging Relationship, ed. Roger Levermore and Adrian Budd (London: Routledge, 2004), 77-92.

[4] During the second half of the 1930s, the British Foreign Office increasingly started to use sport, football in particular, as a very efficient diplomatic tool. See: Richard Holt, ‘The Foreign Office and the Football Association: British Sport and Appeasement, 1935-1938’, in Sport and International Politics, ed. Pierre Arnaud and James Riordan (London: E & FN Spon, 1998), 51-66.

[5] Mihajlo Todić, 110 Godina Fudbala u Srbiji (Belgrade: FSS, 2006), 92-99.

[6] Dejan Zec, ‘The Origin of Soccer in Serbia’, Serbian Studies: Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies 24, no. 1-2 (2010): 137-159.

[7] Srbislav Todorović, Fudbal u Srbiji 1896-1918 (Belgrade: SOFK, 1996), 9-16.

[8] Archives of Yugoslavia (AY), 334-106-393, Report by Franjo Bučar, President of the Yugoslav Olympic Board to the Marshall of the Court, October 15,1920; Vasa Stojković, Beli Orlovi: 1920-1941 (Belgrade: FSJ, 1999), 17. A detailed and very interesting first-hand description of the Yugoslav participation at 1920 Olympic Games can be found in Jovan Ružić, Sećanja i Uspomene (Belgrade: SOFK, 1973), 345-362.

[9] Stanišić, Plavi, Plavi!, 25.

[10] Petar Prokić, Montevideo, 1930. Godine, (Belgrade: Grafocard, 1998).

[11] The very first football match played by the Yugoslav national team, in 1920, had only one starter from a Serbian club, while all the others were from Croatia. This prompted some to question whether the team coach was biased along ethnic and political grounds. On the other hand, the final matches played by the national team in 1940 and 1941 were practically boycotted by Croatian players, for political reasons. See Zec, The Origin of Soccer in Serbia; Milorad Sijić, Fudbal u Kraljevini Jugoslaviji, (Belgrade: Milirex, 2009).

[12] Dejan Zec, ‘Kratak Osvrt na Pojavu Fudbalskih Navijača u Kraljevini SHS/Jugoslaviji’, Glasnik Etnografskog Instituta SANU 64, no. 2 (2016): 217-238.

[13] Dario Brentin and Dejan Zec, ‘From the Concept of the Communist “New Man” to Nationalist Hooliganism: Research Perspectives on Sport in Socialist Yugoslavia’, The International Journal of the History of Sport 34, no. 9 (2017): 1-16; Dejan Zec, ‘Početak Izgradnje Socijalističkog Sporta u Srbiji 1944-1945. Godine’, in Tradicija i Transformacija: Političke i Društvene Promene u Srbiji i Jugoslaviji u 20. Veku, ed. Vladan Jovanović (Belgrade: INIS, 2015), 317-338.

[14] Branko Jurlina, ‘Šport i Politika’, Povijest Športa 26, no. 105 (1995): 37-44.

[15] Fredi Kramer, ‘Uloga HSS u Hrvatskom Športu’, Povijest Športa 25 (1994): 32-43.

[16] John Lampe, Yugoslavia as History: Twice there was а Country, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 113-117, 154-158.

[17] Enes Milak, Italija i Jugoslavija 1931-1937 (Belgrade: ISI, 1987); Jacob Hoptner, Jugoslavija u Krizi 1934-1941 (Rijeka: Otokar Keršovani, 1972), 51-288; Bogdan Krizman, Vanjska Politika Jugoslavenske Države 1918-1941 (Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1975), 22-31, 38-43, 49-61, 92-102.

[18] Stevan Ćirković, Politička i Privredna Mala Antanta (Belgrade: Jugoslovensko udruženje za Međunarodno Pravo, 1935), 3-35; Krizman, Vanjska Politika, 32-37, 62-65.

[19] Mari-Žanin Čalić, Socijalna istorija Srbije 1815-1941 (Belgrade: Clio, 2004), 332-381.

[20] M. C. Kaser, E. A. Radice eds., The Economic History of Eastern Europe 1919-1975, Volume II (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986), 299-309.

[21] There are many written accounts about the sense of allegiance of the Serbian population to their former Allies at the beginning of the Second World War, despite the fact that the Yugoslav government tried to stay neutral. For example, prominent Yugoslav playwright and literary critic Milan Đoković wrote in his memoirs that on the news that the United Kingdom and France had declared war on Germany, crowds of people in Belgrade and other cities came to the streets in jubilation, singing ‘La Marseillaise’ and ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’. See Milan Đoković, Onaj Stari Beograd (Belgrade: SKZ, 1994), 535-602.

[22] Aleksandar Rastović, Velika Britanija i Srbija 1903-1914 (Belgrade: Istorijski Institut, 2005), 45-58.

[23] Miloš Paunović et al, Izbeglištvo u Učionici: Srpski Student i đaci u Velikoj Britaniji za Vreme Prvog Svetskog Rata (Belgrade: Centre for Sports Heritage – SEE, 2016), 384-395.

[24] For detailed accounts on British policy towards Yugoslavia on the eve and during the Second World War, see Mark Wheeler, Britain and the Struggle for Yugoslavia 1940-43 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1980); Elizabeth Barker, British Policy in South Eastern Europe in the Second World War (London: Macmillan, 1976).

[25] Jugoslovenska Sportska Revija, special issue, May 18, 1939, 2.

[26]Peter J. Beck noted an interesting anecdote, which reveals a lot about what Yugoslavs thought about English football in years prior to the Second World War. Philip Noel-Baker (a notable British sportsman, Labour politician and diplomat) recalled talking to a Yugoslav friend of his, Vladimir Dedijer (a football fan, prominent Yugoslav communist and after the Second World War a very important government and football official) in 1938 and asking him if Yugoslavs were interested in world affairs. Dedijer answered that it really depended and that while every schoolboy in Belgrade could answer the question of who Cliff Bastin was (Arsenal footballer), very few knew who Winston Churchill was. See Peter Beck, Scoring for Britain: International Football and International Politics 1900-1939 (London: Routledge, 1999), 36.

[27] Jozo Jakopić, ed., Hrvatski Nogometni Šport 1911-1938 u Spomenici I. Hrvatskog Gradjanskog Športskog Kluba u Zagrebu (Zagreb: Narodne Novine, 1938), 107-126; Svetislav Glišović, ‘Englezi i Futbal’, Danica, 14-16.

[28] Mihailo Andrejević, Dugo Putovanje Kroz Fudbal i Medicine (Gornji Milanovac: Dečje Novine, 1989).

[29] Jugoslovenska Sportska Revija, special issue, May 18, 1939, 2.

[30] Beck, Scoring for Britain, 253.

[31] AY, 71-3.

[32] Pravda, May 6, 1939, 14.

[33] Politika, May 21, 1939, 24.

[34] Beck, Scoring for Britain, 263; Sportista, no. 1138, May 10, 1939, 1.

[35] Sportista, no. 1135, April 26, 1939; Jugoslovenska Sportska Revija, special issue, May 18, 1939, 2.

[36] Pravda, May 4, 1939, 14.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Pravda, May 10, 1939, 13.

[39] Politika, May 9, 1939, 13.

[40] Sijić, Fudbal u Kraljevini Jugoslaviji, 12-18.

[41] Politika, May 16, 1939, 13; Pravda, May 14, 1939, 16; Ivo Šuste, representative of the Croatian football sub-associations, suggested in a press release that Croatians had no alternative but to boycott further matches of the national team and labelled the actions of the Yugoslav FA as ‘political violence’.

[42] Letter of the Zagreb Football sub-association to Yugoslav FA, April 1, 1939, in Sportista, no. 1138, May 10, 1939, 9-12.

[43] Sportista, no. 1140, May 31 1939, 1. The final decision of the Yugoslav FA was to suspend ‘Građanski’ Zagreb and ‘Hajduk’ Split from all domestic competitions on the account that they forced their players to boycott the national football team.

[44] Stanišić, Plavi, Plavi!, 115-116. Jozo Matošić, Šime Milutin, Vili Šipoš, August Lešnik, Mirko Kokotović and Franjo Glaser, all Croats, were either excluded from the Yugoslav team by the head coach Simonović or were forced to boycott the game by their Croatian clubs.

[45] J. A. Mangan, ed., Europe, Sport, World: Shaping Global Societies (London: Frank Cass Publishers, 2001), 257.

[46] Politika, May 17, 1939, 12.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Pravda, May 17, 1939, 11.

[49] Politika, May 18, 1939, 13.

[50] Politika, May 14, 1939, 25.

[51] Politika, May 21, 1939, 24; The ‘BSK’ stadium was the biggest and the best stadium in Belgrade at the time, although it could be considered rather basic in facilities when compared with contemporary football grounds in the United Kingdom. Certain modifications and improvements were made just for the match against England. See Dejan Zec, ‘Money, Politics and Sports: Stadium Architecture in Interwar Serbia’, in On the Very Edge: Modernism and Modernity in the Arts and Architecture of Interwar Serbia (1918-1941), ed, Jelena Bogdanović, Lilien Filipovitch Robinson and Igor Marjanović (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2014), 269-287.

[52] Pravda, May 13, 1939, 11.

[53] Politika, May 3, 1939, 13.

[54] Politika, May 3, 1939, 14.

[55] Politika, May 18, 1939, 13.

[56] Stanišić, Plavi, Plavi!, 117; Stojković, Beli Orlovi, 51.

[57] Pravda, May 17, 1939, 11; Politika, May 16, 1939, 13.

[58] Bora Jovanović and Ljubomir Vukadinović eds., Četvrt Veka S. k Jugoslavije 1913-1938 (Belgrade: Jugoslovenska Sportska Revija, 1939), 80.

[59] Politika, May 19, 1939, 12-13.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Politika, May 19, 1939, 12.

[62] For example, The Manchester Guardian, May 19, 1939, 4, wrote that ‘the weather was suitable for the finest English August afternoons’; Politika, May 20, 1939, 13; Yugoslav reporter from London Predrag Milojević gave the summary of the texts published by the Daily Express and the Daily Mail, who had their reporters in Belgrade.

[63] A report in The Times May 19, 1939, 5, stated that ‘Yugoslavia…played better football than they had ever done before, thus had the distinction of beating England in the first international match between the two countries’.

[64] Politika, May 20, 1939, 13. This was supposedly published in the Daily Express.

[65] Politika, May 19, 1939, 14. Among others, Yugoslav Prime Minister Dragiša Cvetković, Milutin Nedić, Minister of Army and Navy, Mehmed Spaho, Minister of Traffic, Đuro Čejović, Minister of Physical Education, Vlada Ilić, prominent industrialist and the Mayor of Belgrade, various other ministers and higher civil servants, British and Italian ambassadors and others attended the match. Interestingly, Regent Pavle Karađorđević did not come to see the game, despite the fact he was a well-known Anglophile and a sports devotee. There is no proof for the claim that he avoided the match because it would be seen as a clear expression of the popular sympathies for the British, but it does make sense.

[66] Beck, Scoring for Britain, 255. Apparently, the conduct of the audience in Belgrade during the match between Yugoslavia and Italy was so bad that both the Yugoslav FA and political authorities had to issue a formal apology to the Italians. See Stanišić, Plavi, Plavi!, 117.

[67] Politika, May 21, 1939, 24; May 22, 1939, 13.

[68] Politika, May 23, 1939, 14.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Stojković, Beli Orlovi, 51.