As Rachael Jefferson-Buchanan has pointed out just some days ago in her The Conversation article ‘Uniform discontent: how women athletes are taking control of their sporting outfits’ , we can’t fully understand the contemporay advances in Women’s Sports without looking at history. During the Summer Olympic Games in Tokyo, we’ve seen the German National Gymnastics Team wearing full-body suits; and it was only days before, as Jefferson-Buchanan writes –

The Norwegian women’s beach handball team was fined for “improper clothing” during the European Championships in Bulgaria. This was because they were playing in shorts, as opposed to the required skimpy bikini bottoms, which should be “a close fit and cut on an upward angle toward the top of the leg” and have a maximum side width of 10cm, according to the 2014 International Handball Federation regulations

Praising the fact that ‘slowly, female athletes are pushing back on outdated uniform regulations and demanding that athleticism be prioritised over aesthetics’, Jefferson-Buchanan underlines how much recent this ‘rebellion in the ranks’ is. In fact, ‘where now the emphasis seems to be on revealing women’s bodies, the opposite was once the case’.

As an (Italian) scholar of Italian Sports History, I totally agree with Jefferson-Buchanan when she writes that the current sportswomen are willing ‘to oppose dress codes that are based on archaic ideas of what women should look like, often through the eyes of men’: a little journey through 1930’s Fascist Italy could be a good case study to understand how much, in 20th-century Western societies, ‘women’s sporting performances have been historically hampered and sexualised’.

Accepting the year 1925 as the conventional beginning of the Fascist regime, we can look back to understand what was going in Italy, and what might have happened if Mussolini hadn’t take control of the Italian society. In the early Twenties the first national athletics meetings and basketball championships gave some women in the most industrialized city of Northern Italy the chance to participate in sport in a similar way to how their European peers had done so since before the First World War. The very conservative Catholic Italian society wasn’t ready at all for what historian Sergio Giuntini called ‘the body’s revolution’: except for a few open-minded exceptions, no father generally was accustomed to allowing his daughters to take part in sports, and to display their bodies in a way that the “old” women’s sports such as tennis, golf, hiking and horse riding didn’t require them to do.

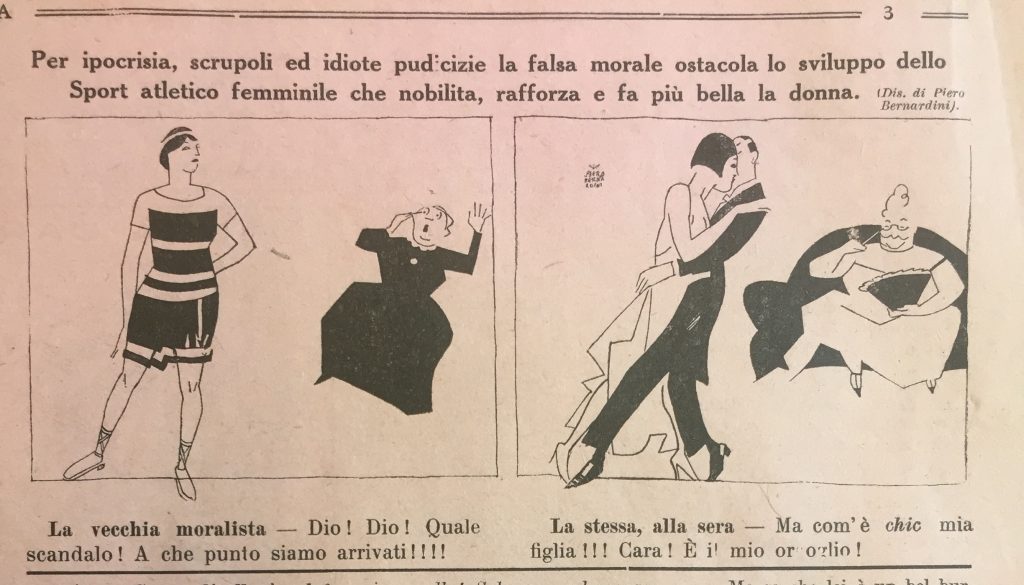

The caption says: ‘Because of hypocrisy, moral qualms and stupid modesty, the false moral hinders the development of the athletic sports, which improve, straighten and make women more beautiful’

The old moralist says: ‘Oh my God! What a scandal! What an awful world to live in!’

The same moralist, in the evening: ‘How fancy my daughter is!!! My dear! I’m so proud of you!’

Source: La Sporta Sportiva, 15/08/1924

Although I use the word skirt for the title of this article, we’ll see how the question was wider than that particular item of clothing: it was about how much a respectable female could show her own body to males not within her familial sphere. That’s why we’ll talk not only about skirts (and their length), but also about other clothing such as tights or leggings and in addition we’ll see how the use of gendered clothes such as ski pants/torusers was still considered a little controversial.

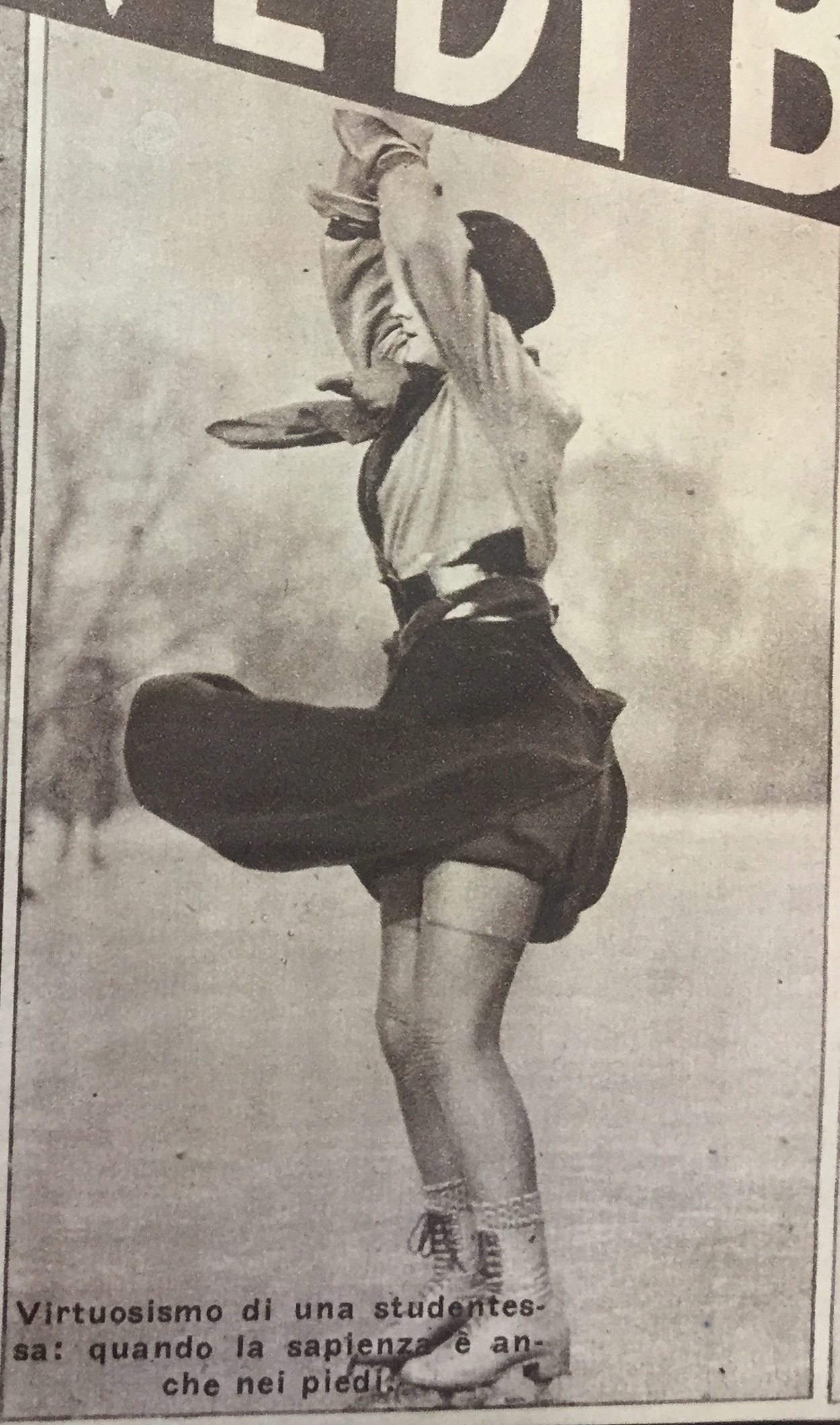

Before talking about the ‘new’ women’s sport, we should say something about ice skating and skiing, the only two winter sports practiced by Italian girls during the Fascist Ventennio (1925-1943). Beginning with the ice-skaters, they seemed to have few problems. As long as they wore tights, thus hiding their bare legs, the length of their skirts were of little importance, their attire was acceptable because it was likened to a ballet tutu.

- Two very rare published picture of female iceskaters in which the demise of tights is apparantly depicted

- Source: Illustrazione Del Popolo, 12/02/1933, pp. 11-12

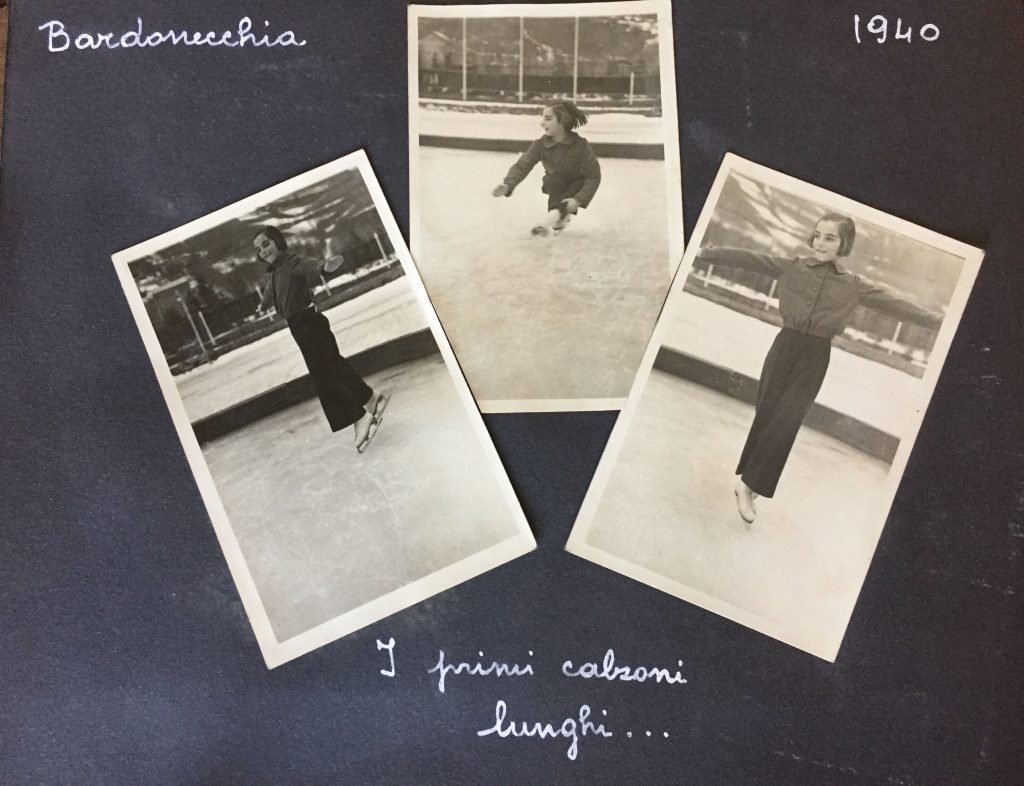

Women skiers had even more problems: the first females who dare to ski in Italy would wear long skirts but in the 1920s’ women, both single and married, started to wear pants or trousers, for very obvious reasons. Yet ski pants were deemed somewhat scandalous because not only did they show off the female form but they were also a traditional male symbol, which is why in one of the very early photos in Grazia Barcellona’s album, the young iceskater recalled the first day in her life when she had worn trousers (it was too cold, in Bardonecchia, on that day!).

Source: https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/gender-and-sport/flipping-through-grazias-photo-albums-flashbacks-from-the-career-of-a-1940s-1950s-italian-figure-ice-skating-champion-part-2/

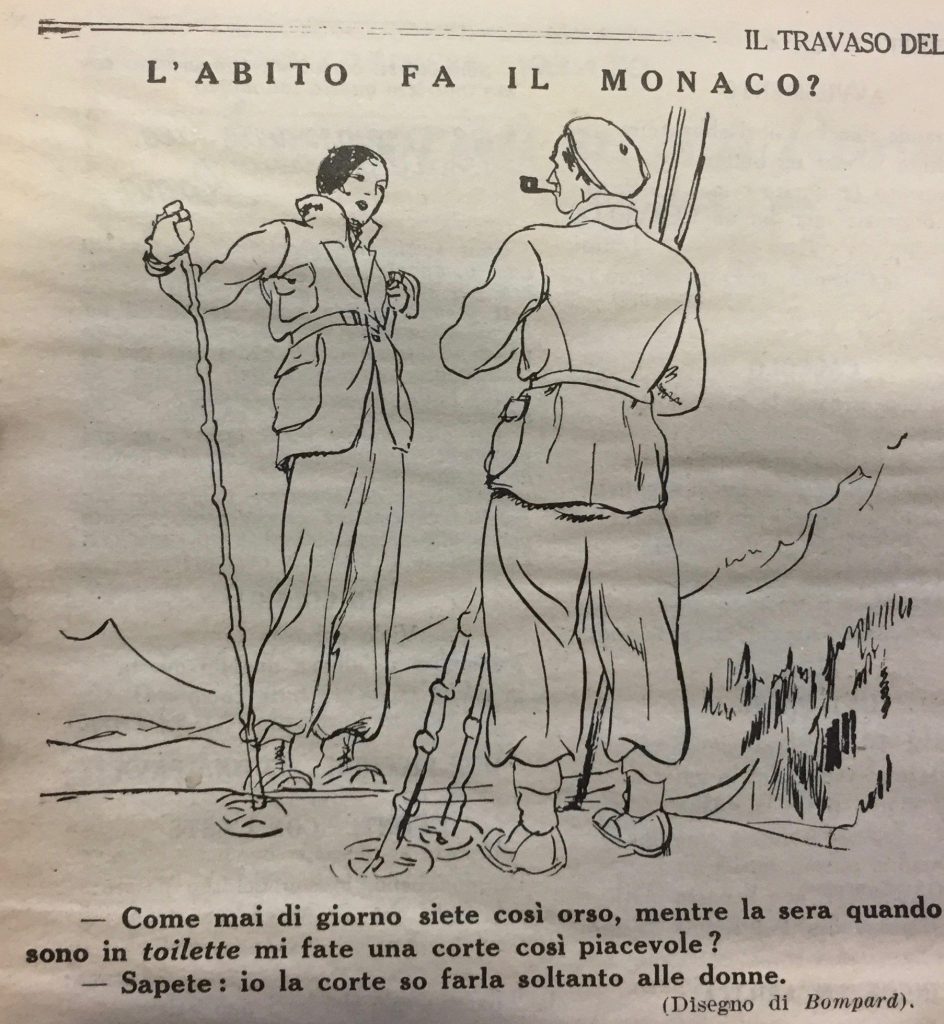

While there was perhaps not a real fight or controversy against ski trousers at the time, except for the old-fashioned conservative ideals, a subtle irony in that regard was still to be found in the early Thirties, especially in the satirical newspapers …

Title – ‘Clothes don’t make the man’

The girl asks: ‘Why during the daytime are you so discourteoustowards me, but when I dress up in the evening you woo me so pleasantly?’

The man answers: ‘You know … I can woo only women’

Source: Il Travaso delle Idee, 14/02/1932, p. 3

This second joke is about the ‘campaign against female skiers in a male suit’

What happened is that a young lady was criticized by some friends for wearing male attire:

so she quickly returned home and removed the jacket, trousers, and male collared shirt and wearing a short evening dress – went back to their friends.

‘That’s better. Women’s outfits must be respectable’

Source: Guerin Meschino, 19/02/1932, p. 2

The title says ‘Good costumes – Female skiers wearing male suits are not allowed to enter the churches’

The female skier is saying ‘After all that has happened between us, now all you have to do is marry me’

The male skier replies: ‘That’s impossible. You know that you are not allowed to enter the church’

Please note that the main title ‘buon costume’ could be translated either as ‘nice suits’ or as ‘’a question of morality’

Source: Guerin Meschino, 19/02/1933, p. 7

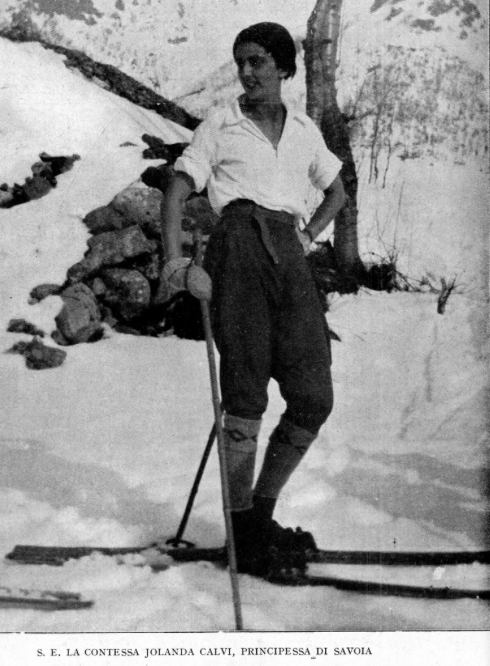

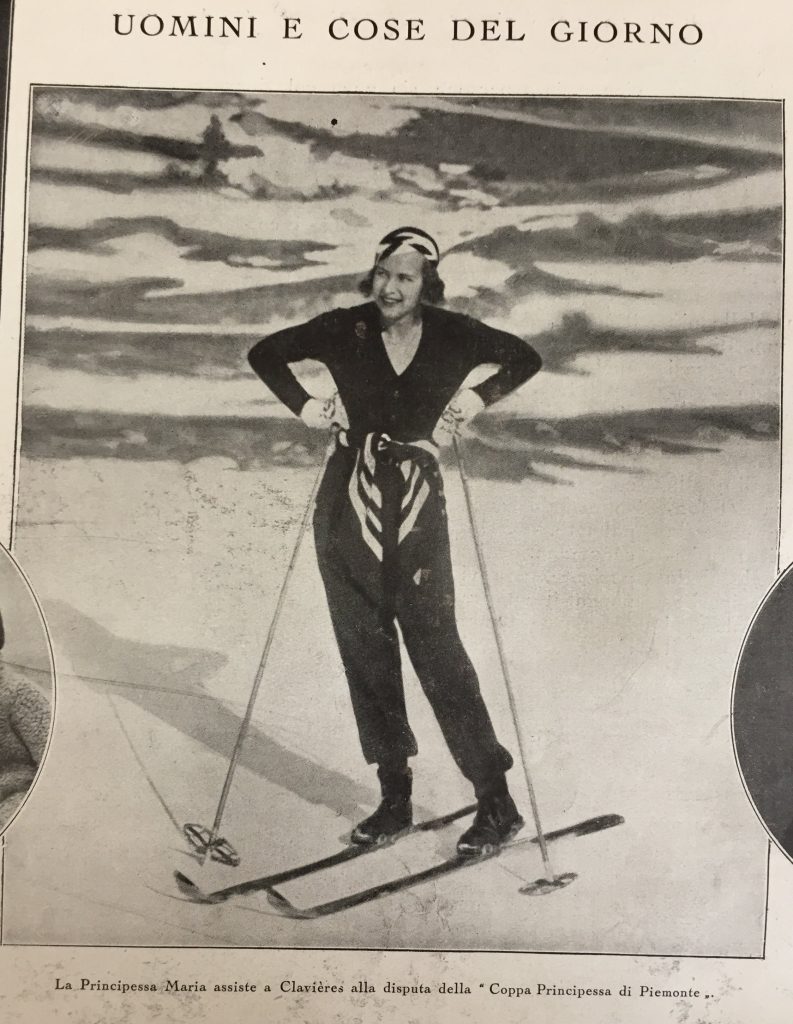

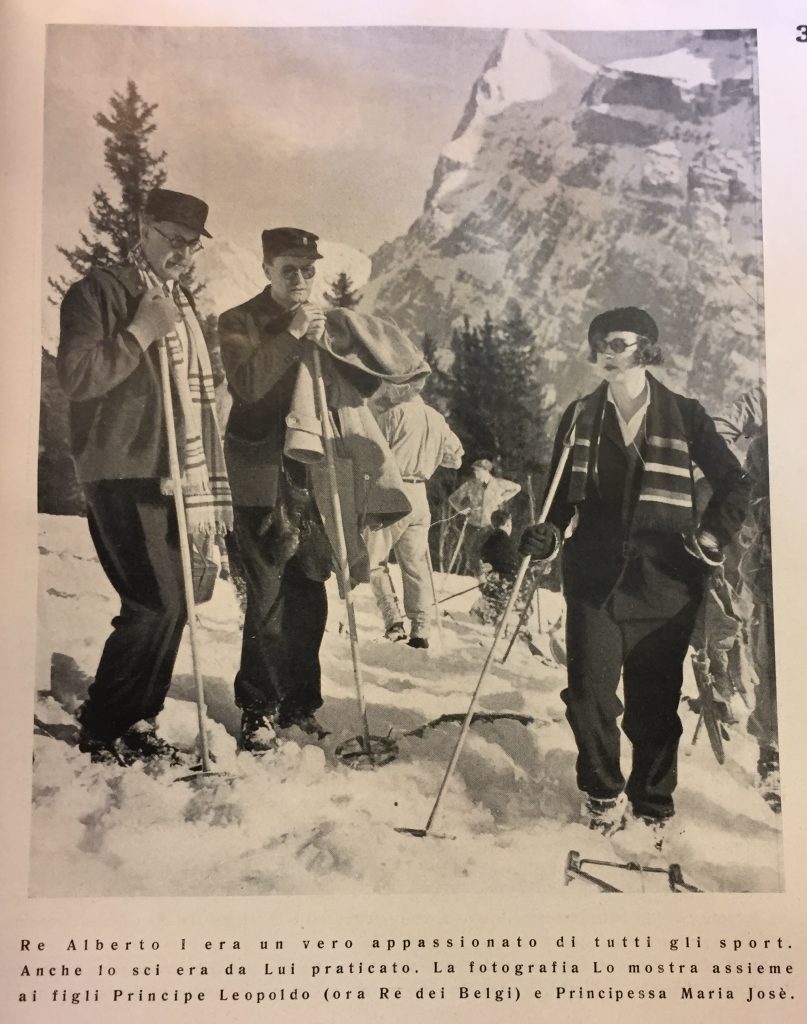

An indirect but very powerful aid to Italian girls wanting to wear ski pants without causing any scandal came directly from the Royal Palace. In fact, the new generation of the Royal Family worn ski pants: and who would dare to accuse Her Highnesses Princess Iolanda (b. 1901), Mafalda (b. 1902) and Giovanna (b. 1907) or even the beautiful young Belgian wife of their brother Umberto, Princess Maria Josè (b. 1906), of being immoral?

We know from private photographs that when Maria José climbed Cervino in 1941 she wore trousers (see https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1417174572999352321 ), or that in the summer of 1940 her older daughter Maria Pia wore shorts just like her younger brother Vittorio Emanuele during the family holiday in the mountains (see https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1417136030310965249 ): but when such images were published by the Italian press, we could imply that they were an indirect but supportive way of allowing modern sportswear to be worn by the uncertain female subjects. After all – how could Their Highnesses be wrong?

On the occasion of her engagement to King Boris III of Bulgaria

La Gazzetta dello Sport praises Princess Giovanna for her sking ability

Note she is wearing ski-pants

Source: La Gazzetta dello Sport, 06/10/1930, p. 3

Princess Iolanda of Savoy in a sking outfit

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, April 1929, p. 16

Princess Maria José skiing (1932)

Source: L’Illustrazione Italiana, 21 febbraio 1932, p. 258.

Maria José was taught a lot of sport by her father King Albert of Belgium

Who later died during a mountaineering accident in 1934

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, Marzo 1934, p. 3.

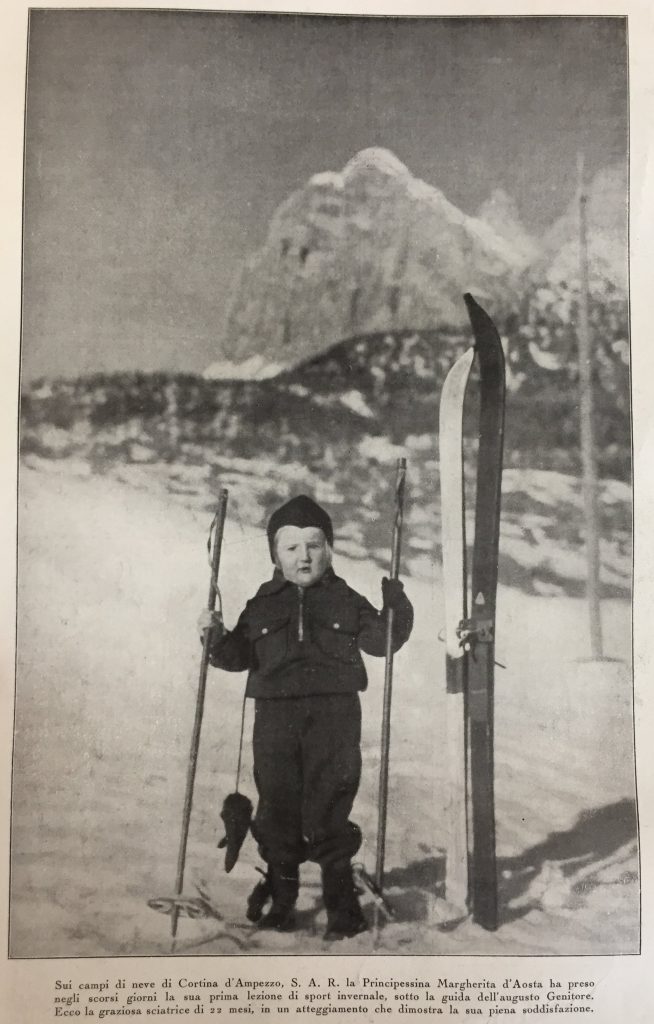

An example of the fashion of the future princesses

This 2-years old baby is Margherita, daughter of Amedeo, Duke of Aosta (cousin of King Vittorio Emanuele III)

Source: L’Illustrazione Italiana, 28/02/1932, p. 272

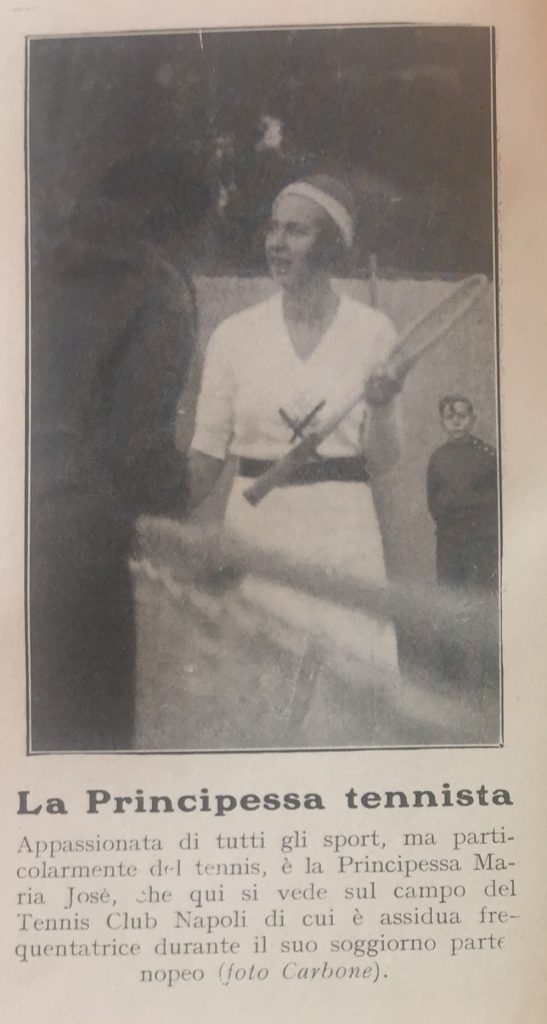

Princess Maria José was also photographed playing tennis. Even this sport, which was the main sport among Italian women of all ages, caused a short lived controversy regarding the dress of the female players. In this particular case the controversy wasn’t born in Italy, but came from abroad, althought it did have an Italian chapter.

Princess Maria José playing tennis (1932)

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1236405152719962112

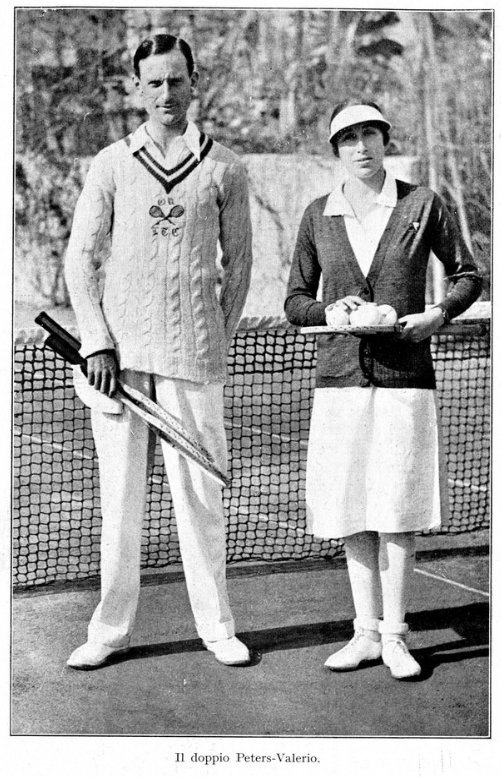

Until the summer of 1933 the standard tennis outfit was, not only in Italy but all around the world, long trousers for men and skirts for women.

Peters and Lucia Valerio, the most important tennis players in 1930s’ Italy

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, Aprile 1929, p. 98

The lovely fashion history video by the Olympic Channel refers to female tennis outfits during the Interwar period.

Source: https://youtu.be/4OwZ1SLcOp4

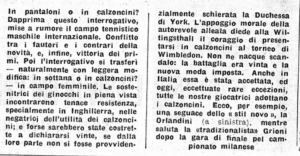

Then, in Summer 1933, the Italian press started reporting what was happening outside the national borders: a few male players such as Austin, Cochet, Merlin, Fischer, and Ellmer had begun to play in shorts: and this revolution spread to their female colleagues, such as Jacobs (USA) and Round and Scriven (UK). The humous sports magazine Guerin Meschino made up a sort of fictional debate about the female tennis players outfit, including Helen Wills Moody, Suzanne Lenglen and Helen Jacobs as speakers: Helen was against female wearing shorts, Jacobs for it, and Lenglen … only concerned about herself!

An illustration from the Guerin Meschino article

Source: Guerin Meschino, 27/08/1933, p. 6

For Guerin Meschino the fashion revolution was reduced to a new opportunity for girls to show off their legs to the audience …

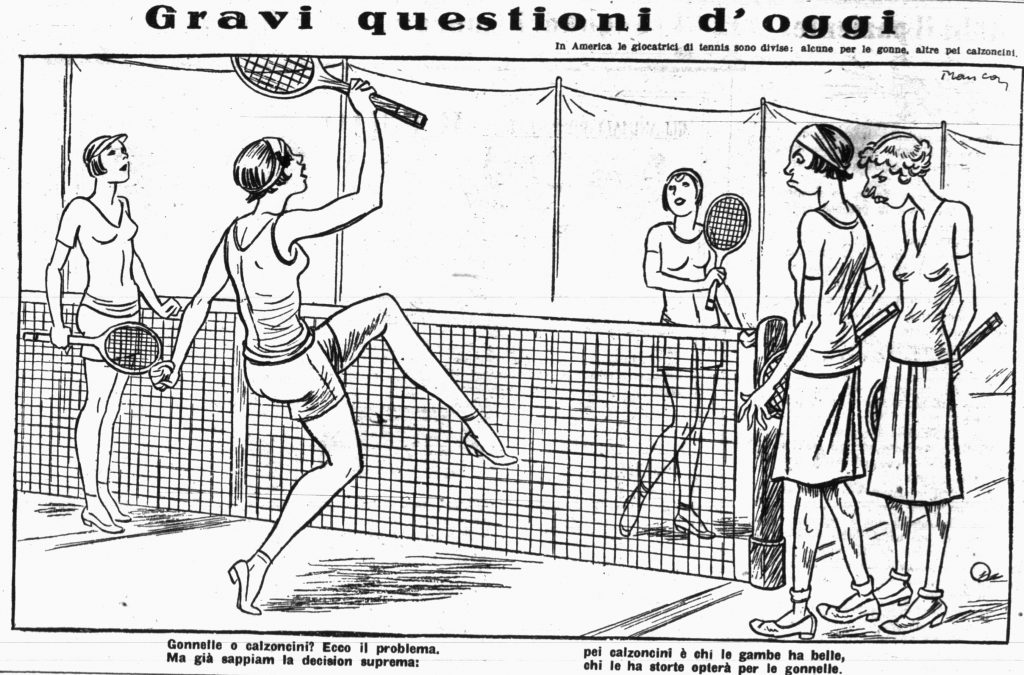

The title: ‘Serious issues of our world’

The caption says: ‘Skirts or shorts? That’s the question. Yet we already know the answer: those with hot legs wear shorts and those with bandy legs wear skirts’

Source: Guerin Meschino, 27/08/1933, p. 6

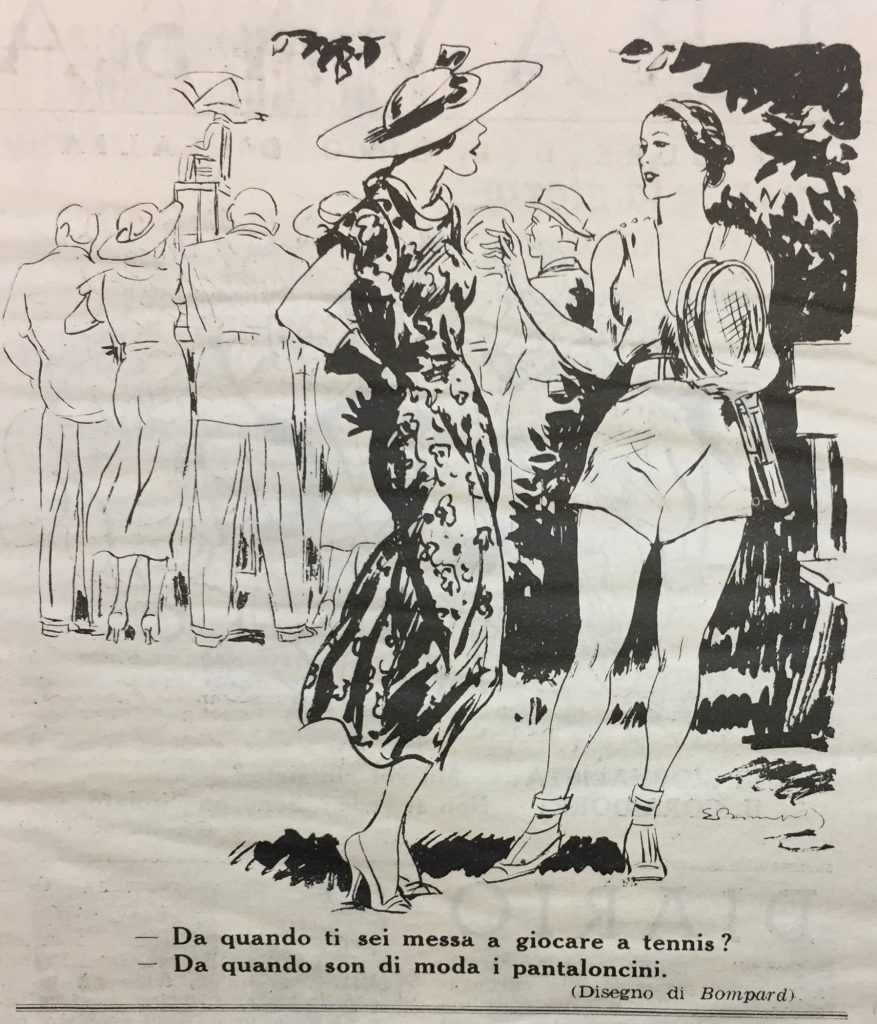

One year later, the question had spread to the amateur tennis playerss

The first woman: ‘When did you start playing tennis?’; the second: ‘Since the shorts became trendy’

Source: Il Travaso delle Idee, 03/06/1934, p. 5.

A year later, the situation in Italy was that most female players wore shorts with just a small minority still wearing skirts – Source: Il Littoriale, 26/10/1934, p. 4

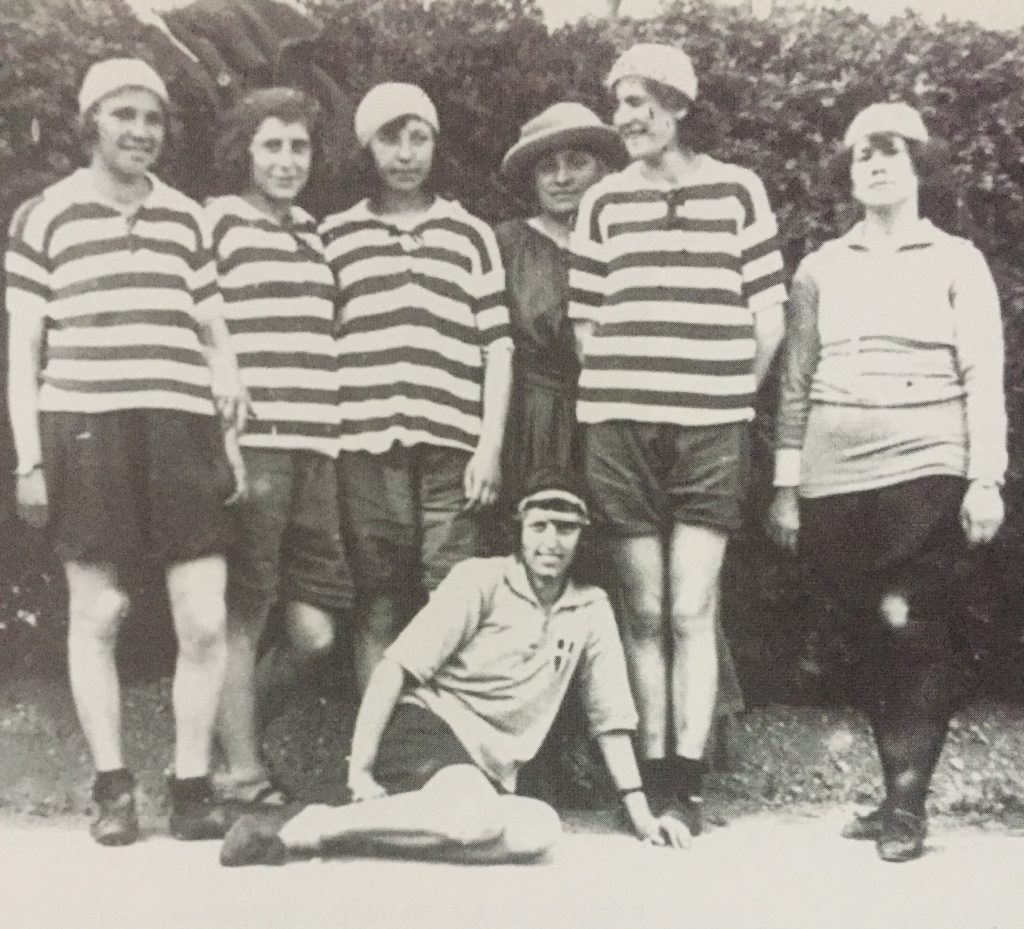

Basketball and above all athletics, the two more innovative women’s sports of the early Twenties in Italy, played a big role in the fashion revolution. During those years, the outfits of the player’s slowly changed: with a more comfortable fit became the main aim. In 1921, some athletes from Northern Italy (i.e. those of Pro Patria club from Busto Arsizio, an industrial city north of Milan) started to wear puffy type shorts rather than the traditional style of athletic skirt; but they were still wearing dark tights or leggings, in order not to show their naked legs.

The Pro Patria relay in Milan, 1921

Source: https://bit.ly/2VjTSZO

Just one year later, in Rome, the 4 Pro Patria relay members are not wearing dark leggings, as opposed to their colleague on the extreme right, who was.

Source: https://bit.ly/2VjTSZO

Gradually the skirt became shorter and tighter fitting …

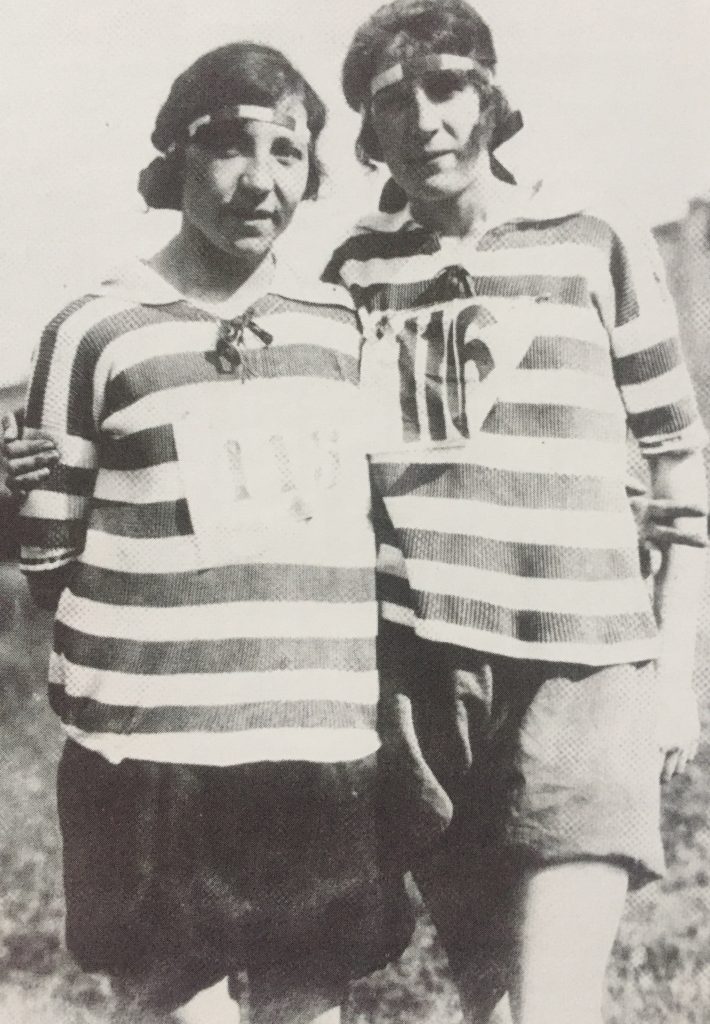

Pro Patria athletes Maria Piantanida and Lina Banzi in 1920s’

Maria’s skirt is around the knee, but Lina’s is mid thigh

Please note also their Roaring Twenties headband …

Source: https://bit.ly/2VjTSZO

What we should underline is that this fashion revolution wasn’t homogeneous, at all: as always happened in Italian social history, the change was welcomed in some more open-minded Northern cities such as Milan, Turin, Trieste, and Bologna, but still not accepted in other minor towns.

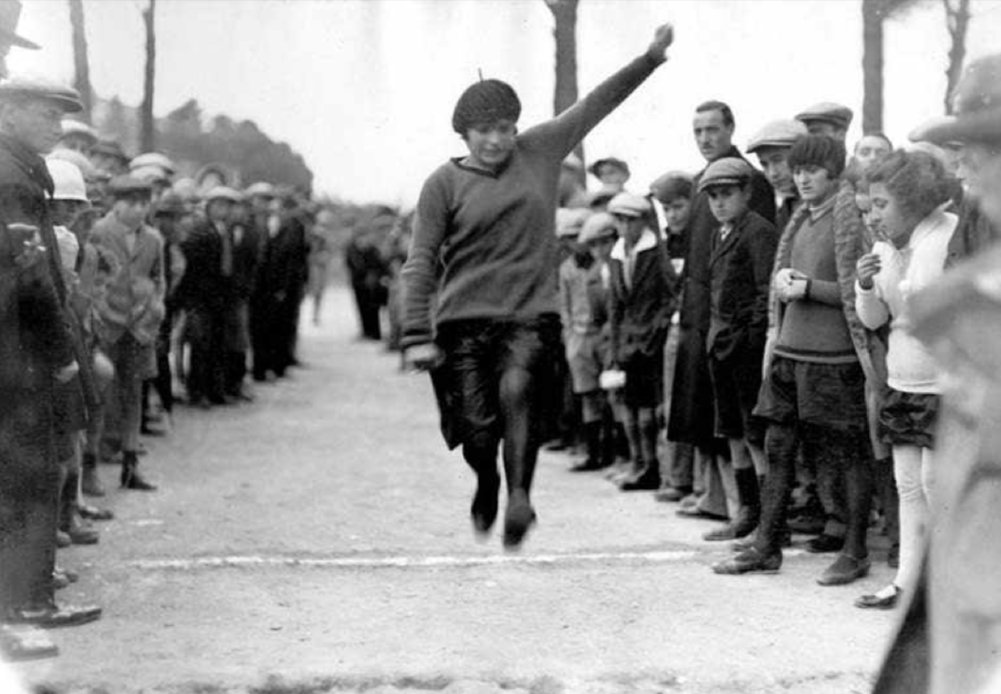

Derna Polazzo (Trieste) winning a 100m race (1928)

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1233806559270121472

Long jump in Macerata (November 1928)

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1233806559270121472

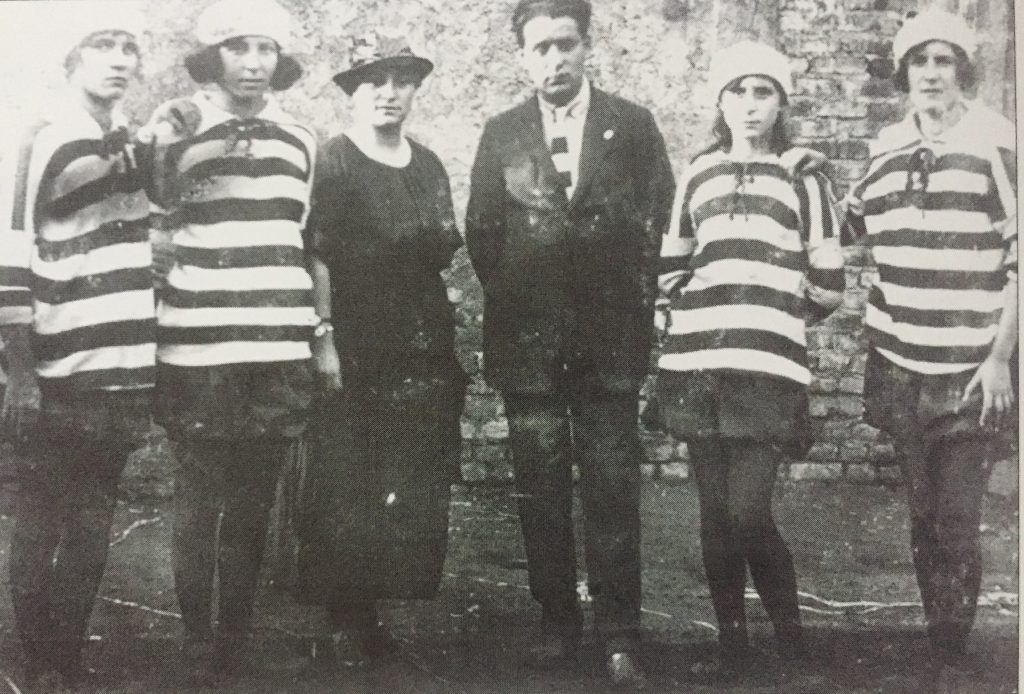

A very interesting photo, taken at the 1929 National Women’s Athletics Championship and depicting that year’s champions with manager Marina Zanetti at the centre of the group, shows how much the situation was heterogeneous, by the end of the Twenties. At the end of the sporting event, some athletes are wearing tracksuits, some dark leggings, and some shorts, of varying lengths

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, Gennaio 1930, p. 38

Article © of Marco Giani

Read Part 2 of this discussion paper HERE