The author would like to express thanks to Levio Bottazzi, Maura Quiriconi and Jole Romano Giordanafor having shared their memories. Thanks also to Levio Bottazzi for having shared some pictures from his personal archive, and to Lyana Calvesi for doing the same with her mother’s (Gabre Gabric) archive. Some photos are courtesy of Gherardo Bonini.

PLEASE NOTE – Express permission is required to reproduce ANY of the images taken from these personal archives – please contact Playing Pasts or the author for more details.

To Read Part 1 Click HERE and for Part 2 Click HERE

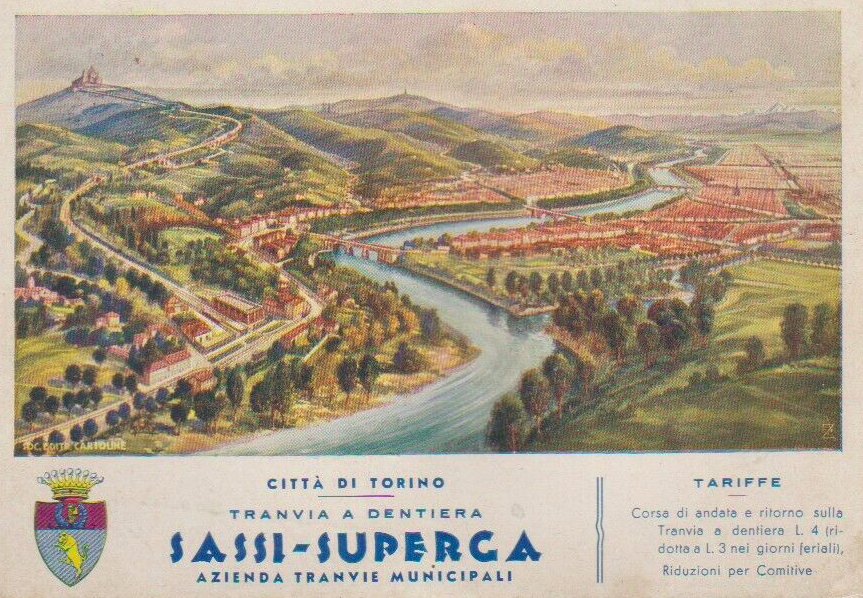

The Olympic relay with the apex of Lydia’s career: she competed for a little while longer, before withdrawing. Ondina Valla went on competing into the late Thirties, by which time she had to face younger opponents. In the 1939 Italian National Championship, the 15-years old Elda Franco from Turin won the high-jump title: just one month before, she had won a bronze medal behind Ondina Valla and Modesta Puhar in the same event. The young student (born in 1924) was the daughter of Damiano Franco, a SIP electrician, both a colleague and a friend of Vezio Bottazzi, and Assunta Lambert, a woman from Savoy who spoke both French and Italian. Since Damiano longed to have a son, he raised his daughter in a very unconventional way, teaching her to ride a motorcycle like he used to do recklessly in the hills around Turin. In particular, Damiano held, for some time , a record in the Sassi – Superga race, a local motorcycle race very popular in Turin.

The Sassi Superga race is 4.9 km long, with a vertical drop of 447m (from 223 to 670)

The average gradient is 9%, but in some points it rises to 18%!

Source: https://sportfolks.net/superga-in-bici-salita-milano-torino/

Using this postcard, we can see the track of Sassi Superga tramway

The hill of Superga is on the left, the city of Turin on the right, on the banks of the river Po

Source: http://bit.ly/3rrWShO

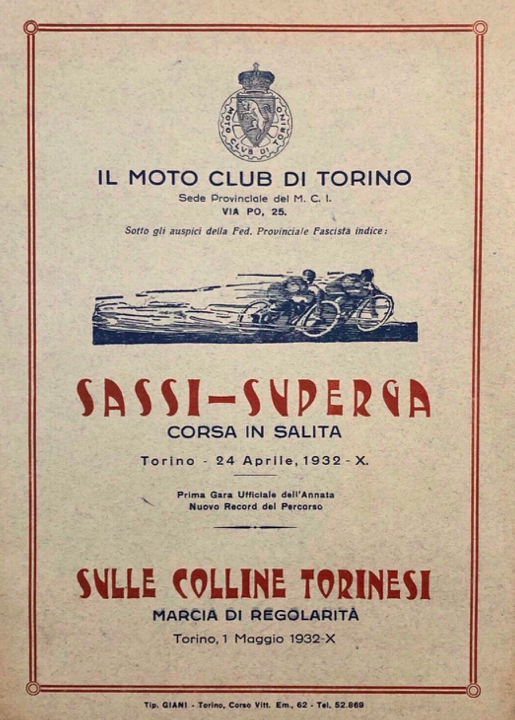

The programme for the 1932 edition of the Sassi Superga race

Source: http://bit.ly/3qogHWa

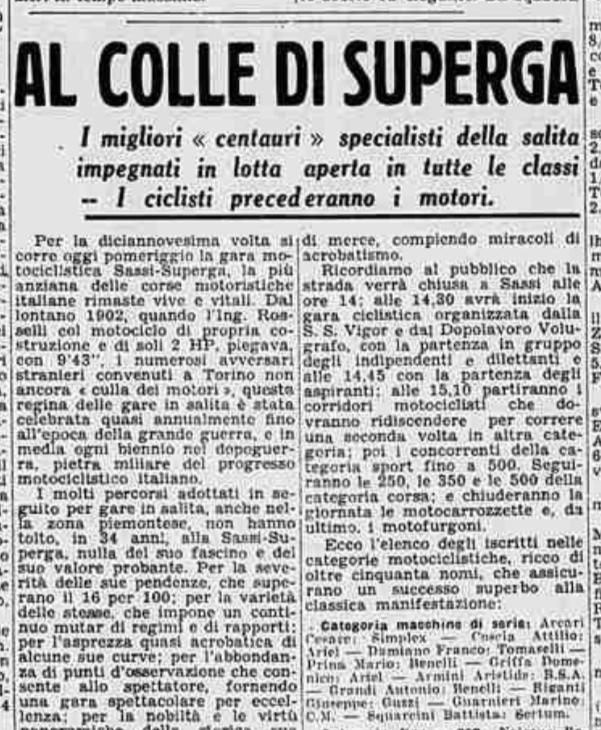

In this article about the 1936 edition of Sassi Superga race, the name of Damiano Franco can be seen among the riders

Source: La Stampa, 18/10/1936, p. 4.

A bend of Sassi Superga (1939)

In the background, the Basilica of Superga can be seen

It was near this point, ten years later, that the Grande Torino airplane crash took place

Source: http://bit.ly/2MVF3ZG

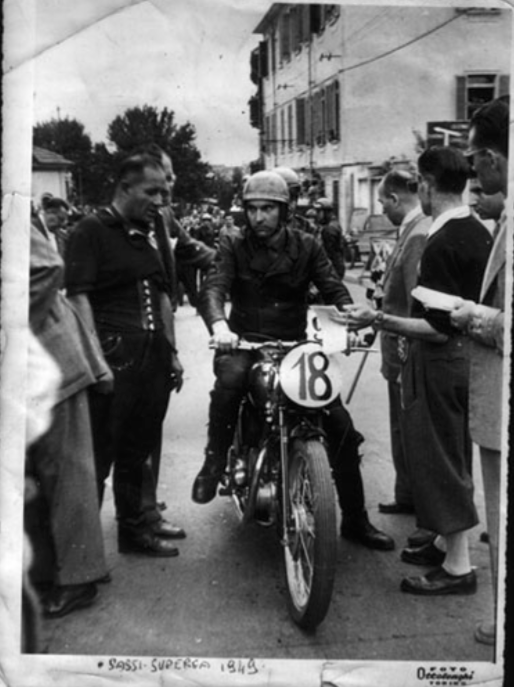

Luigi Gilardi joining the 1949 edition of Sassi Superga motor race

Source: https://www.gilardimoto.it/la-storia/

Damiano encouraged Elda to practice sports, and she did under the colours of DAS Turin. It was at the 1941 Italian National Championship, held in Modena, where the real generational change of guard happened: Elda won the 80m hurdles (12” 6/10), Ondina Valla was 3rd; a year later, competing in her hometown, Elda repeated the feat – A star was born!

Meanwhile, the Second World War had begun, causing the cancellation of the 1940 Olympic Games. Unlike their male colleagues sent to the front, Italian female athletes carried on competing, but they faced an increasing number of sporting problems, such as organizing an international meeting. After Italy entered into the war (May 1940), the Italian National women’s athletics team challenged first Germany (July 1940, in Parma) and then Hungary (July 1942, in Budapest). At this second meeting Elda Franco was called up for the first time, winning 80m hurdles gold in 12” 4/10, and the silver medal in long-jump (5,33m). Maura Quiriconi can still remember her mother Elda telling her about that interminable train trip to Budapest. Due to the harsh war conditions, she and her Italian teammates had very little to eat, but once in Budapest, they realized that their Hungarian opponents were quite literally starving!

As Playing Pasts’ readers already know, thanks to Grazia Barcellona’s story (see https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/gender-and-sport/flipping-through-grazias-photo-albums-flashbacks-from-the-career-of-a-1940s-1950s-italian-figure-ice-skating-champion-part-2/ ), in the first part of WW2 the Axis countries organized many international sports events: teams and single athletes from Germany, Italy, Hungary and all occupied territories such as Croatia were called to compete, in order to build a new sporting Europe under the Nazi swastika.

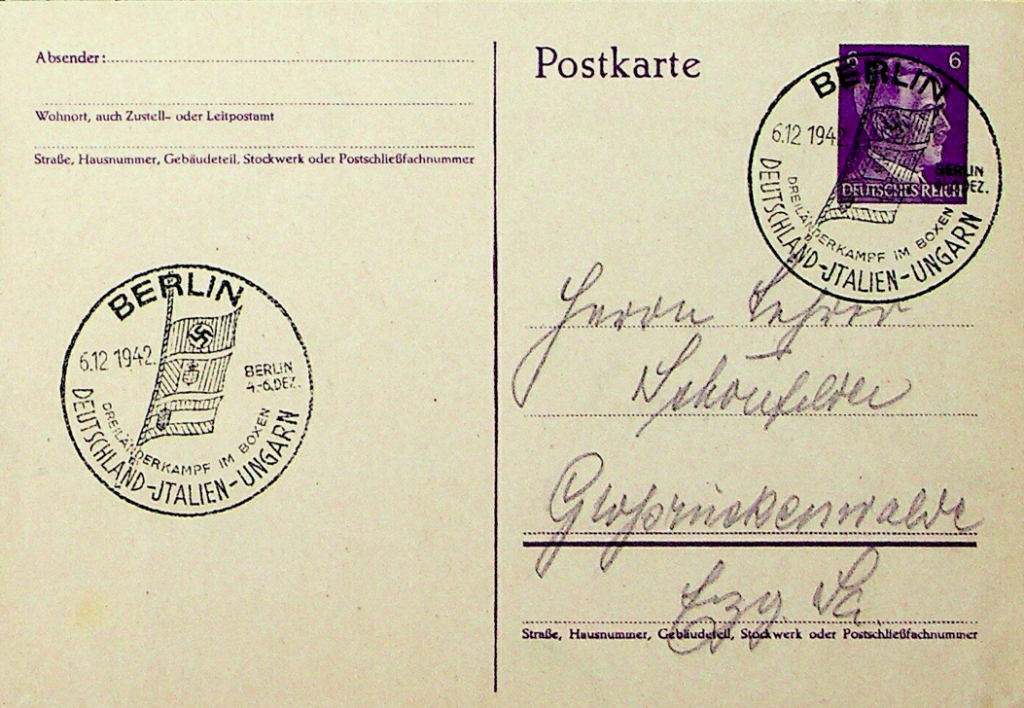

A postcard recalling a boxing meeting held in Berlin in December 1942, among German, Italian and Hungarian athletes

Source: http://bit.ly/3uj7nWI

Since the men had been sent to the front, youngsters (such as 13-years old ice skater Grazia Barcellona and Carlo Fassi, were sent to compete in Zagabria in 1942) and it was the women were the main participants of these Axis sporting events: the principle one took place in Milan, between 24- 27th September 1942. The 1st (and last) edition of the Campionati Sportivi della Gioventù Europea ‘European Youth Sports Championships’ which was a big propaganda event: the local GIL (the youth association of PNF) not only had to host all the foreign representatives from across Europe (Germany, Hungary, Croatia, Netherlands, Slovakia, Spain, Belgium, Denmark, Norway, Bulgaria …), but also to uphold Italy’s name on the athletics field.

The Championship’s programme: the cover was drawn by F. Mauro

Source: Fonte: https://bit.ly/2ZaONkE

After a majestic parade of athletes in traditional dress, that took place in the streets of Milan, they all gathered in the Arena Civica for the sporting events (see this 20’ video: bit.ly/3c1GjEQ). Here the Italian women athletes were called on to challenge their unbeatable German colleagues. They were not expected to beat them, but it was very important for the overall medal table not to lose too many points: they did it! In the final women’s athletics ranking, Germany was 1st with 239 points, Italy 2nd with 221 points, Netherlands 3rd with 176 points; in the general ranking, Italy was 1st (83 points), Germany 2nd (71,5), Hungary 3rd (63,5).

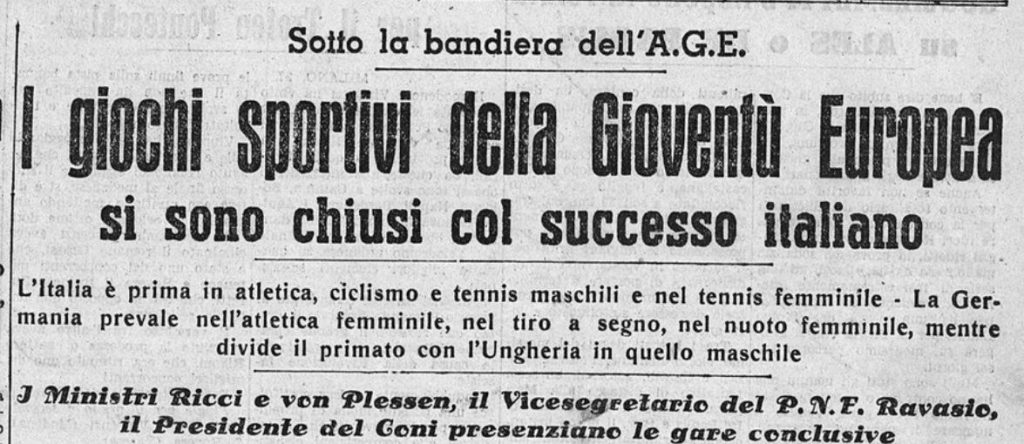

The heading by sports newspaper Il Littoriale, praising Italy’s final victory

Source: Il Littoriale, 28/09/1942, p. 1.

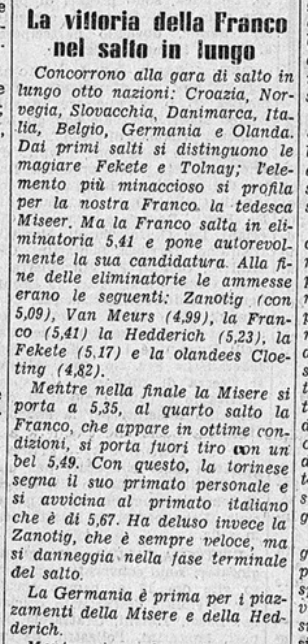

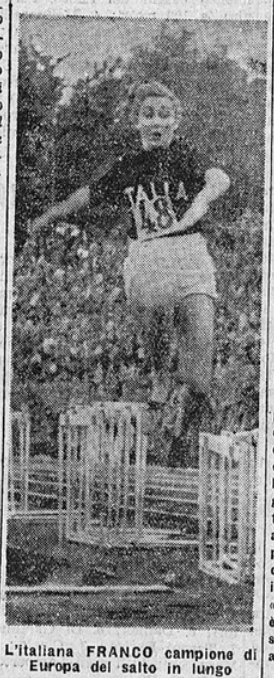

Elda Franco played an important part in this excellent performance by the Italian women: wearing her number ’48’ shirt, she won long-jump gold (5,49m) and silver in 80m hurdles (12” 3/10).

-

Elda Franco’s victory in the long jump event

Source: Il Littoriale, 26/09/1942, p. 1

-

Elda Franco during the long jump event: the caption calls her ‘European champion’

Source: Il Littoriale, 28/09/1942, p. 1

Looking at the award ceremonies pictured by the Italian press (https://bit.ly/3aC0Q1o and https://bit.ly/37xO2Yb ) we can still see a smiling Elda carrying out the Roman salute in the fading light of that summer day: we may find ourselves wondering if any of the former GFC calciatrici, such as the Boccalini sisters, were among the audience, applauding Elda’s outstanding performances. The fact is that one year later, when Fascist Italy collapsed, Elda (who competed for one last time in Rome, in May 1943) decided to join the Resistance rather than the RSI forces.

While her father Damiano played a big role in the Turinese resistance, Elda, who had meanwhile secured employment as a clerk, joined the SIP left-wing combat group Brigata Arduino in honour of two Turinese sisters killed by the Fascist militia on 12th March 1945.

-

The 16-years old Vera Arduino[left]

and her 18-years old sister Libera

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eccidio_della_famiglia_Arduino

Like many of her peers, Elda’s role was that of dispatch rider, staffetta in Italian: in a twist of fate, it’s the same word used to mean ‘relay’: but this time, she didn’t have to run, but rather to ride a bicycle – in fact, the Nazi-Fascist forces were unwilling to frisk women, which meant that they were free to hide messages beneath their clothes. At the same time, in Brigata Arduino, there was another Turinese athlete who had climbed the corporate ladder to become the President’s personal assistant. Lydia used all her relative power and secretarial know-how to help the Resistance information network, with the approval of her boss, the Neapolitan lawyer Attilio Pacces. A very important document given to me by Levio Bottazzi proves that not only had Lydia joined the Brigata Arduino in 1943, but also that in the very beginning she was the chief of it, before being replaced by Vezio Bottazzi.

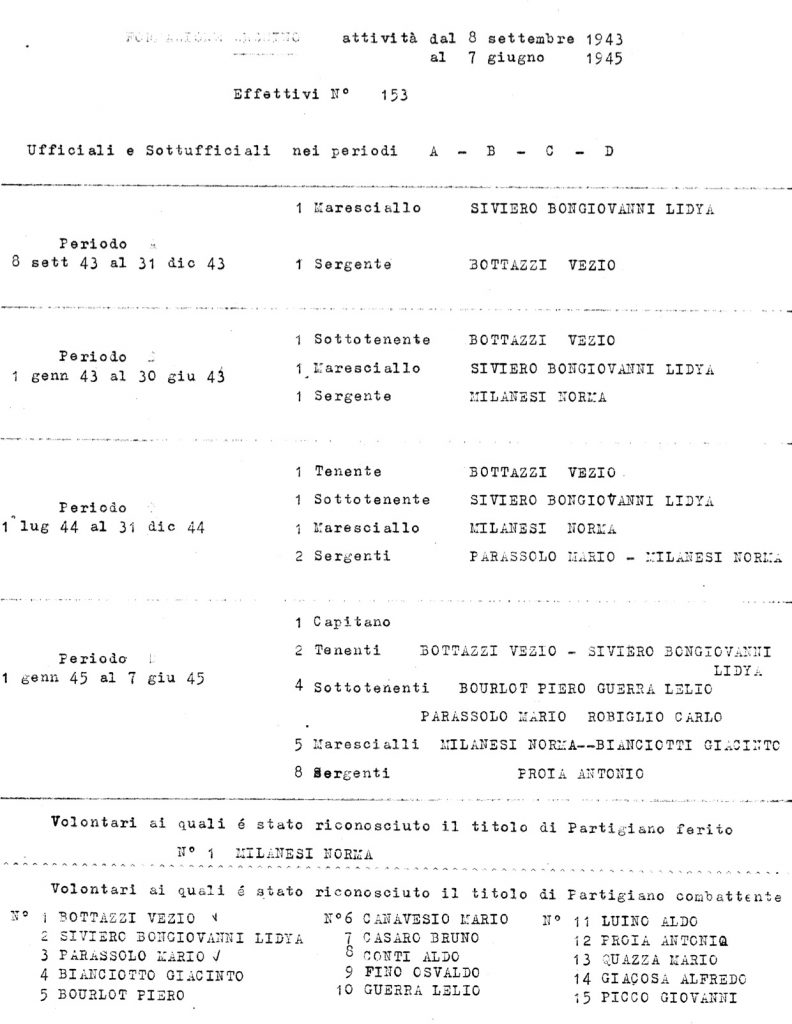

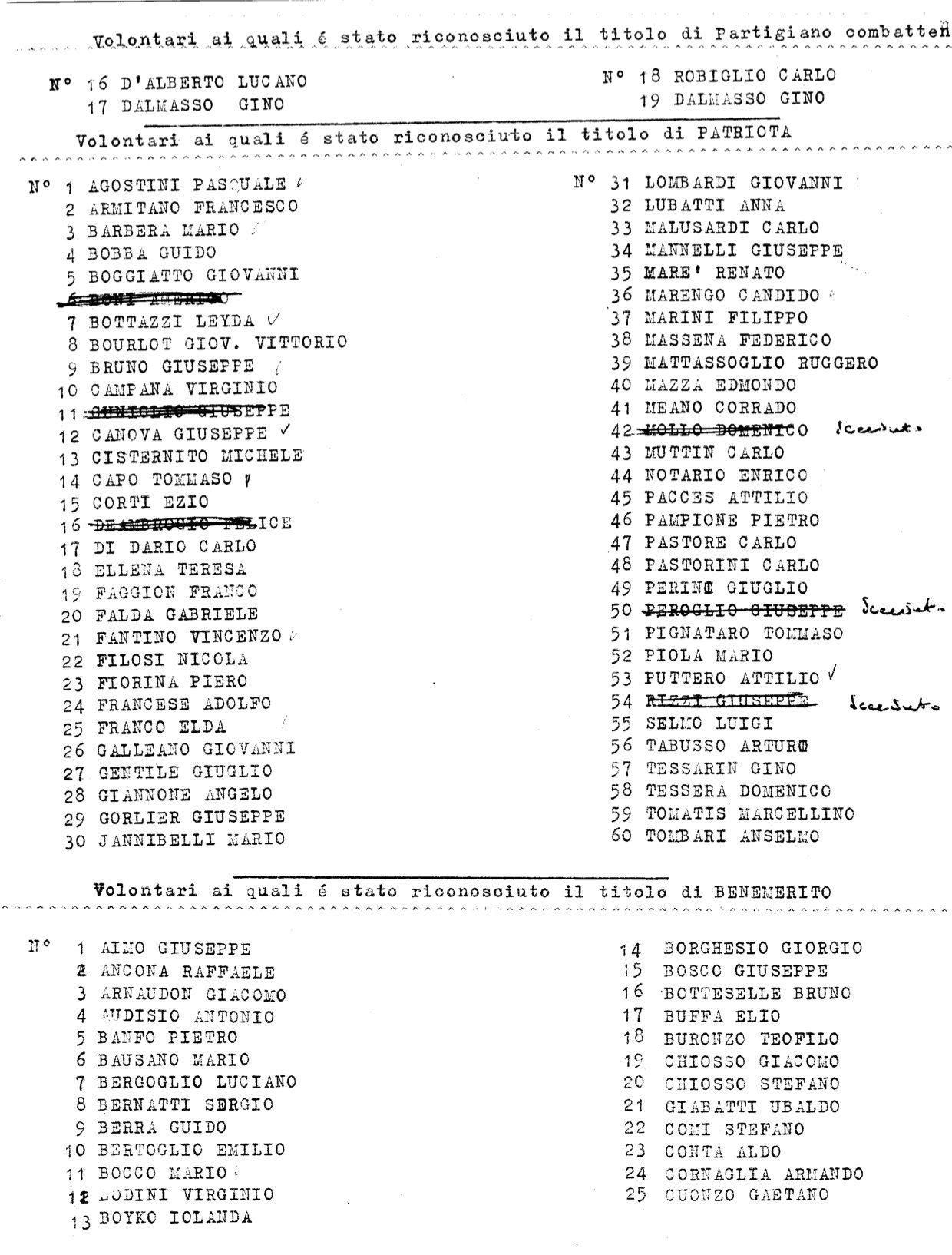

The type-written document that shows the internal organization of the Brigata Arduino

Source: Archivio personale Levio Bottazzi.

On this page Elda Franco’s name is quoted, as a simple member (“patriota”) of the Brigata

Source: Archivio personale Levio Bottazzi.

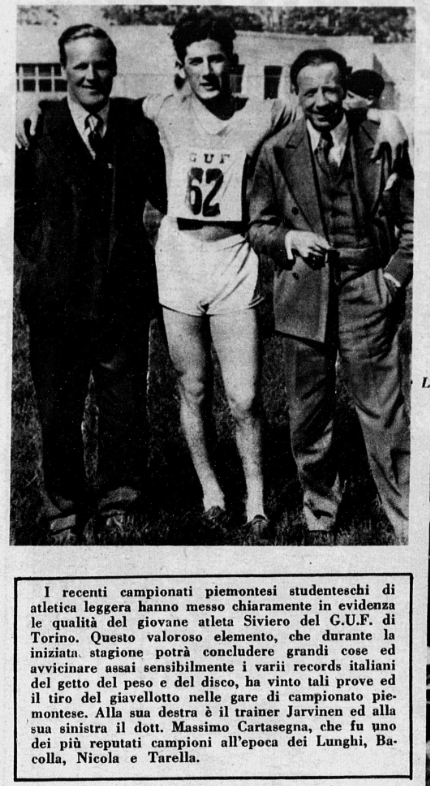

The thrower Carlo Siviero (1934)

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 10/04/1934, p. 10.

Carlo Siviero between coach Jarvinen and former champion

Massimo Cartasegna

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 29/04/1934, p. 15.

The fair palace in Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, 68

Where Lydia Bongiovanni was raised by her mother, and returned to live during WW2, after the separation from her husband

Talking about marriages, let’s return to Angelo Tollini, who in 1940 had separated from Levio’s aunt Leida. When the Nazi army occupied Turin in mid-1943, they had to find a new Prefetto, one who could be welcomed by the population: he should be fluent in the German language, but not too involved with the Fascist Party. The local Reich Consul, baron von Langen had an idea: the moderate Angelo Tollini was the perfect candidate. In September 1943, after a long hesitation, Angelo accepted the post, but he was fired after only a few weeks, due to his contrasting opinions with the Fascist authorities (not the German ones). After escaping from Turin in 1945, thanks to the bishop and his brother-in-law Vezio’s protection, Angelo started to work in Livorno for … the Americans! He became manager of the ARAR, the Italian state corporation who handled the Allies’ munitions dumps in the late 1940s; he died in 1951.

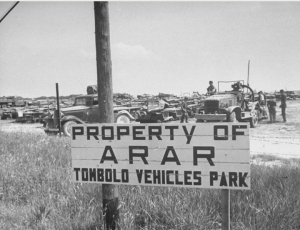

Angelo was the head of ARAR camp located in Tombolo, near Livorno

The above two images were taken in 1945

Source: https://forums.g503.com/viewtopic.php?t=219820

Going back to the final days of the war, in April 1945, when the Nazi-Fascist forces (unlike what happened in Milan) would be to fighting door to door before surrendering. Thanks to Levio’s eyewitness account, we can see just what a brave and cool-headed character the former athlete Lydia was, perhaps we could even speculate that a very long sporting career had helped develop this. In the very last days of the war, the Nazis sealed off the population: no private phone worked in Turin. The only way to communicate was using the SIP internal electrical wires: the Germans used theses to communicate with their colleagues in Milan. In order to do so they had to meet the boss’s personal assistant, Lydia, a very elegant secretary who just 9 years before had been competing in those famous Olympic Games in Berlin! Lydia used to welcome them in Pacces’ office offering them tea and pastries, then chatted with them. The soldiers started to trust Lydia: she looked so imperious when she called the 15-years old boy Levio, ordering him to take the messages brought by the German hosts to the broadcast office downstairs. The fact was that everybody in that office was a member of the Resistance: so Lydia, keeping a cool head was a fundamental for source of the enemy’s information.

After war, life began to return to normal. Elda once again began to compete, until 1948: in 1950, she married a SGT basketball player, Bruno Quiriconi. Meanwhile, in May 1946 Elda, Lydia, Amelia Piccinini (a former calciatrice from Alessandria, see http://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/football/playing-in-heeled-shoes-in-milan-and-winning-olympic-medals-in-london-some-new-discoveries-about-the-pioneers-of-italian-womens-football/ ) and Franca Audifredi signed a public appeal: imploring all Italian sportsmen and sportswomen to vote for the Republic in the upcoming 2 June 1946 institutional referendum. Elda, Amelia and Franca further suggesting to vote for the Partito Comunista Italiano (PCI).

The May 1946 appeal

Source: L’Unità, 17/05/1946.

Life gave Lydia a very happy twist. When WW2 ended, in May 1945, a young Austrian Porsche-employed engineer, Rudolp Hruska (b. 1915), who had been working for the German occupation forces in Northern Italy in the previous year on a tractor project, was hiding between the Italian and the Austrian border. Everybody, in the motor racing world, (such as his friend Tazio Nuvolari) knew that Rudolp was a genius: so in 1947 Piero Dusio, head of Cisitalia, was able to secure from the Porsche corporation the services of both Rudolf Hruska and Carlo Abarth. The Cisitalia 360 was the masterpiece of the Austrian engineer.

The Cisitalia 360 at the Porsche Museum

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cisitalia_360

There in Turin, the successful engineer met a nice woman, who was fond of sports … Rudolf and Lydia got engaged (their actual marriage date is unknown as yet). Jole Romano Giordana remembered that not only both Lydia and Hruska used to ski together at the Sestries, but that sports had a big role in the development of their relationship. In fact, they both used to play tennis in the glamorous Turinese tennis club called ‘Sporting’. Jole still recalls Lydia telling her that Rudolf professed his love for her in a lovely park, near to the tennis court.

In the early 1950s, Lydia started to work with a very bold Milanese manager, Giuseppe Luraghi (1905-1991). In 1950, Luraghi worked for a short time at the SIP, in Turin: then he moved to Finmeccanica, the most important state mechanical corporation in Italy. Luraghi understood that the famous Alfa Romeo (an industry controlled by Finmeccanica) was undergoing a major crisis: it required new ideas, and men willing to work hard to relaunch the company. Luraghi appealed to Lydia’s partner: which proved the right choice. Designing the famous Giulietta, Hruska was fundamental in the transformation of Alfa Romeo from a racing house to car manufacturer.

Alfa Romeo Giulietta, Third Series (1961)

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfa_Romeo_Giulietta_(1955)

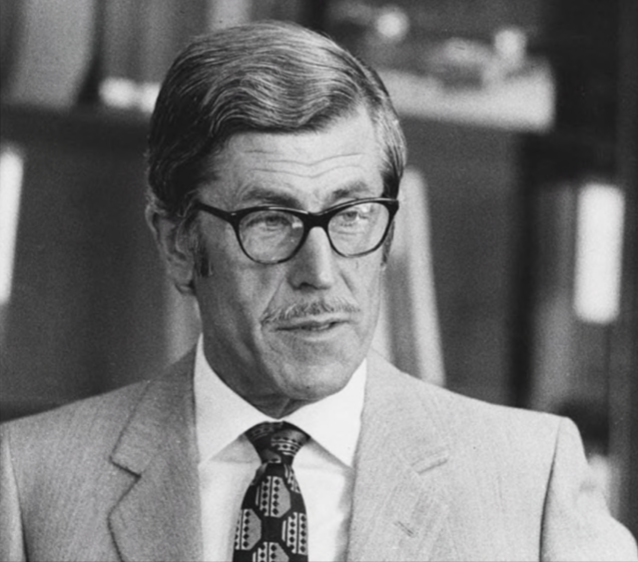

Rudolf Hruska (1915-1994)

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudolf_Hruska

An Alfa Romeo Giulietta Sprint (1958)

According to Jole Romano Giordana, Hruska gave to his wife such a sport car (or a similar model), which she used to drive, even in old age.

Image Credit: Di Riley from Christchurch, New Zealand – 1958 Alfa Romeo Giulietta Sprint, CC BY 2.0

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38923286 Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfa_Romeo_Giulietta_Sprint

It was reported the during weekends Hruska used to undertake little trips in order to test prototypes, with his wife Lydia in the car with him. We can only imagine the sensation of the feeling speed … “roll down the windows and let the wind blow back your hair”, Bruce Springsteen would sing some years later. It’s nice to imagine that during those moments Lydia might have recalled another kind of speed and one that her husband Rudolf couldn’t understand: that of running, baton in hand, in the Berlin Olympiastadion. The crowd, the memory of her dead father, the braveness required to run in the first place and the tall profile of Ondina running towards her at the first change of baton, the Dutch opponent at her side slightly ahead. She needed to speed up …

A young Lydia, praised for her 1930 standing high-jump record

Source: La Stampa, 21/03/1930, p. 5.

Article of © Marco Giani

Read Part 4 of this series HERE

For more on Lydia Bongiovanni:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1139214350605070338

For the complete list of Italy women’s athletic National Team international meetings (1927-1950), see:

For more images about Marina Zanetti, see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1080826986199769088

For images about 1931 Olimpiade della Grazia in Florence, see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1020403024395726848

For more sources about Angelo Tollini, see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1139793795883708416

For more images of Italian women’s athletics movement in 1936 (Olympic Games included), see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1051404332321710080

For more images about prince Umberto of Savoia at 1936 Berlin Olympics, see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1363240047999344640

For more images about the 1942 Campionati Sportivi della Gioventù Europea, see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1151906140810371072

For the Italian transcription of the two 2019 interviews to Levio Bottazzi, see:

https://www.academia.edu/45087024/Interviste_a_Levio_Bottazzi_14_06_2019_e_09_08_2019_

For Italian sources about the carriers of Lydia Bongiovanni and Elda Franco, see: