Part 6 tells the story of Brunilde Amodeo – PLEASE NOTE all of the images of Brunilde Amodeo in this article are taken from the ‘Archivio privato Brunella Bracardi’ (Milan, Italy),and reproduced her with the kind permission of Francesco Bacigalupo. Express permission is required to reproduce ANY of the images in this article – please contact Playing Pasts for more details

To read the previous articles in this series please see the links below

Part 1 – bit.ly/2NBMzZg Part 2 – bit.ly/2JKczw6 Part 3 – bit.ly/38ACGl8

Part 4 – bit.ly/36AWHWA Part 5 – bit.ly/2vo8I4P

One of the thorniest problems, working on female sports history sources is the change of sportswomen’s surnames. In early 20th century Italy, women used to play sports until they got married: after marriage, they changed their surname, taking their husband’s name. This is a huge problem, above all when the historical research of heirs has to face a double generational leap, with a second surname change.

Last summer, after some research in Municipality of Milan’s Registry Office (which, due to its privacy policy, can only release to scholars very little biographical information, such as the date and place of birth, but nothing about the children of the deceased), I started to sift through all the main Milanese cemeteries, to find more biographical information about the 1933 calciatrici. I was really lucky with Brunilde Amodeo, captain and central halfback of one of the GFC teams: I found the family tomb, where Brunilde (d. 2000), her husband Bianco Bracardi (d. 1971) and their daughter Brunella (d. 2016) had been buried. Checking in the 2016 newspapers’ obituaries, I discovered that Francesco was the name of Brunella’s son. Although I couldn’t find Francesco’s surname, I had discovered in Milan’s Registry Office, Brunilde’s last known address, so I went there, hoping that Francesco, Brunilde’s grandson, was still living in his grandmother’s house.

When I got there in late September 2019, I suddenly saw that the building had a lot of intercom bells: I was in a quandary, should I ring each of them? I decided to ask the doorman for some information: had he known an old woman called Brunilde Amodeo? He looked at me with some suspicion, avoiding answering clearly, although I explained to him that I was a sports historian. To overcome his (dutiful) suspicions, I showed him a photo depicting Brunilde as a footballer, taken from a 1933 newspaper. I had succeeded in convincing him and he phoned someone in the building, explaining to him who I was. Then he directed up to an upstairs apartment, where a man was staring at me from behind a door. When I showed him the photo I was holding in my hand, he said: ‘I know that picture’. I left the building two hours later, after having had a coffee while reading through Brunella’s memories and listening to Francesco talking about his grandmother’s life.

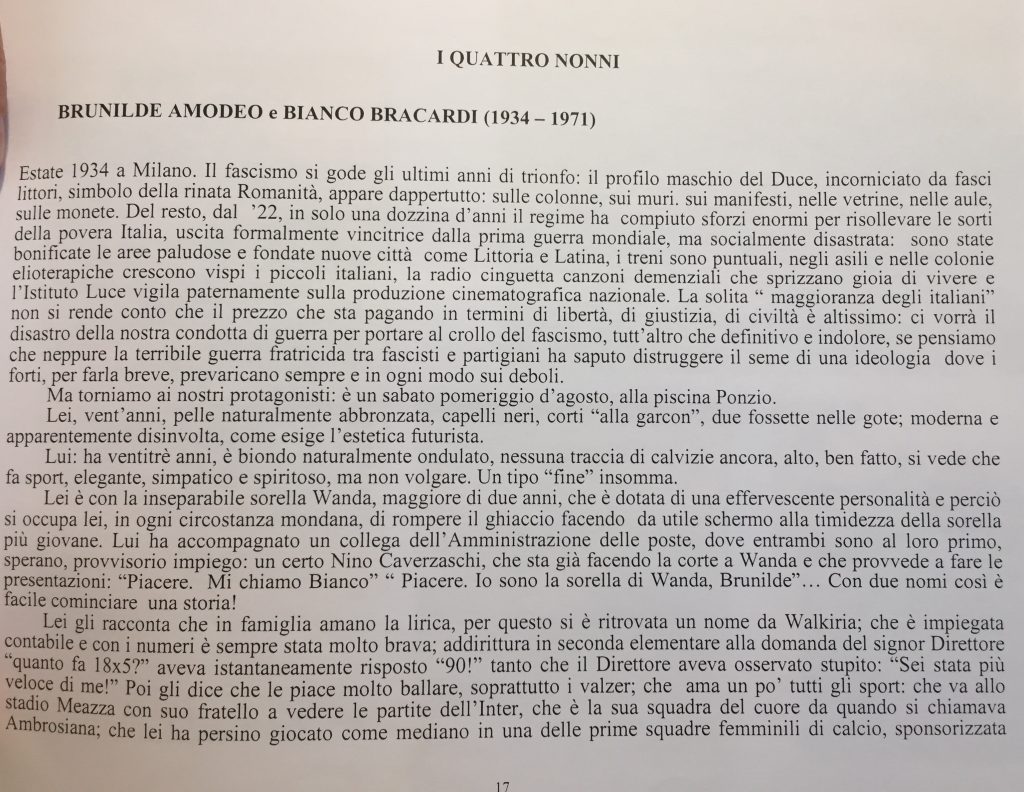

Before sadly passing away in 2016, in December 2009 Brunilde’s only daughter Brunella Bracardi (later Bacigalupo), one of the first women to graduate in Civil Engineering from Milan Politecnico, was able to write down the family history, which she called Gli amori dei nonni ‘Forefathers’ love stories’. In each chapter, Brunella tells her son about the life of each generation of ancestors and of course, a chapter is devoted to Brunilde and Bianco.

- The first page of ‘Gli amori dei nonni’s’ chapter about Brunilde and Bianco

-

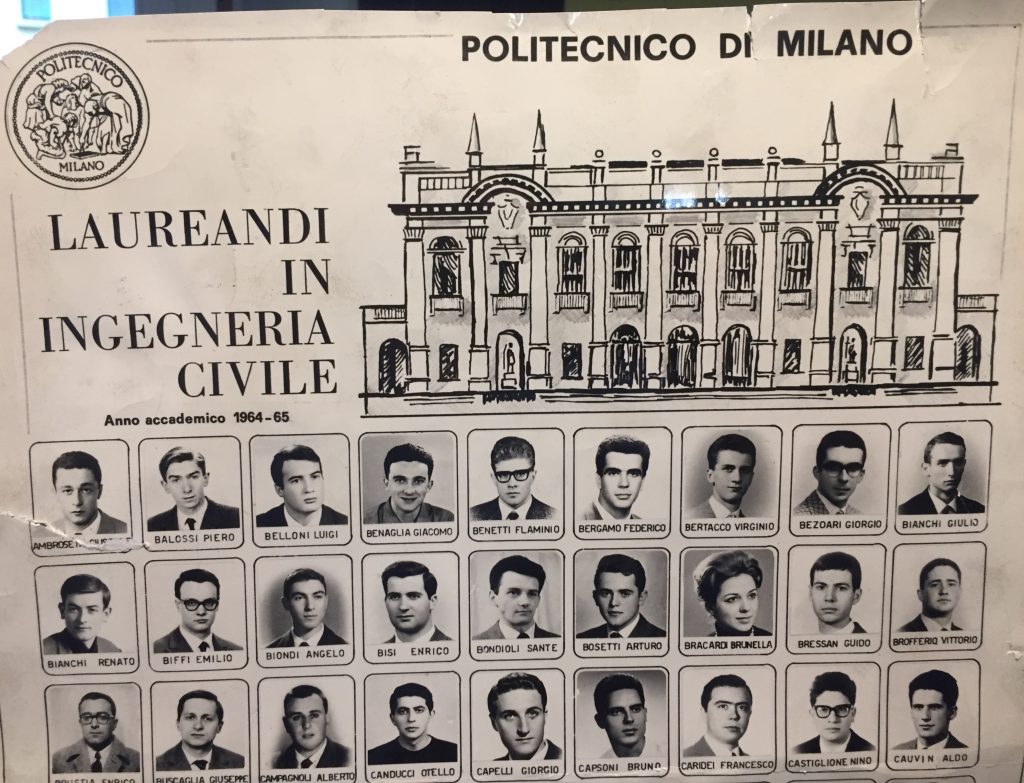

The upper part of the 1964/1965 Civil Engineering graduates at Milan Politecnico poster:

As you can see, Brunella Bracardi is the only woman.

Francesco told me that when he was a child, he didn’t like to study

His grandmother, Brunilde, used to pull him in front of this poster, telling him to remember who his mother was and to behave accordingly

.

Angelo and Anita Amodeo moved from Abbiategrasso (a little countryside town) to Milan: they had one son, Bruno (b. 1907), and two daughters, Wanda (b. 1912) and Brunilde (b. 1914). After living for some years in via Vetere (Porta Ticinese district), they moved to Porta Vigentina district, near Forza e Coraggio sports centre; in the late thirties they were going to move permanently to the Città Studi district, very close to Giovanna Boccalini Barcellona’s school.

Brunilde (whose name was chosen because of her parents’ love for opera) was a modern girl, ‘a la garçonne’, or a short-haired girl, she also had quite a dark complexion. She worked as an accounting clerk and when she was just a little girl, she impressed her headmaster with her ability to be able to perform multiplication sums very quickly. Brunilde loved to dance, especially waltz, as well as the cinema, with her favourite actor being Leslie Howard.

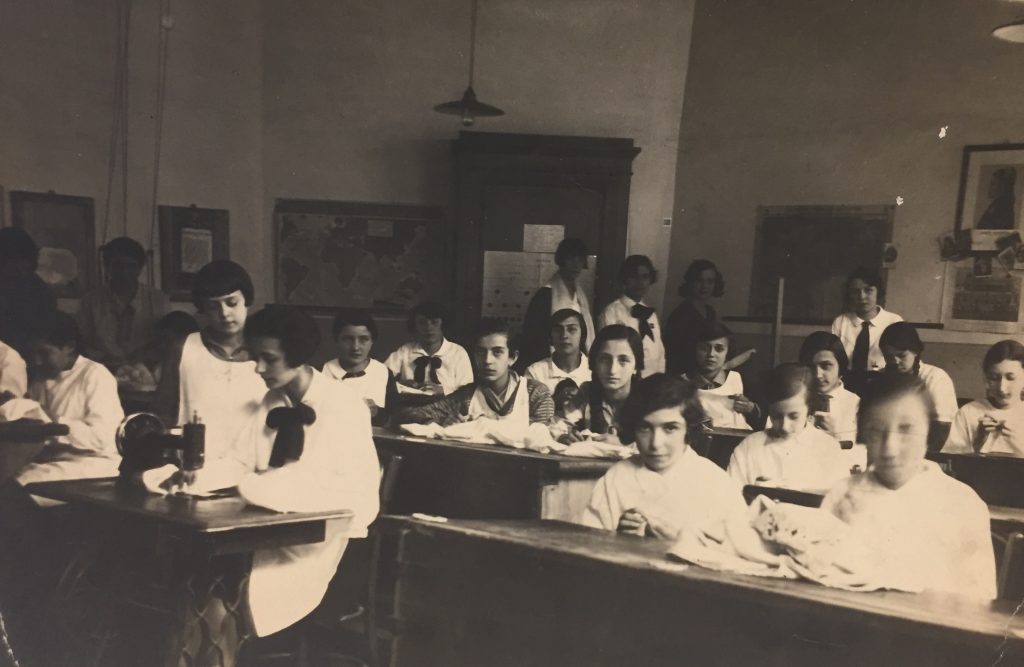

Brunilde is the girl looking into the camera on the right in the first image and is on the right of the three in front of the first window in the second image, taken during some lessons in school. The first, a sewing lesson and the second a typewriting course. These were normal courses for female students at that time, those who attended would hope to become mill workers or tailors, and typist. Remember that the GFC was full of tailors and typists.

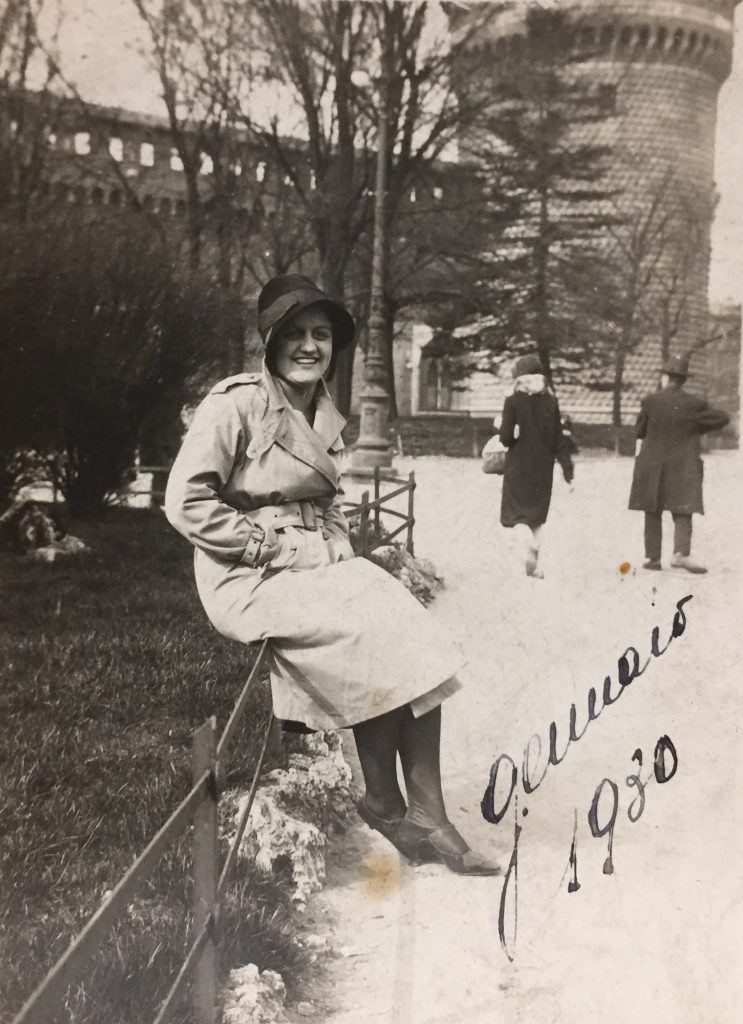

- Brunilde in front of Castello Sforzesco, Milan (January 1930)

- Brunilde, on the right, in front of V Triennale exhibition, Milan (1933)

-

Brunilde in front of Amodio’s new house in Città Studi district (late 1930s).

Her clothes give the impression that she came from a fairly wealthy family

Brunilde and her elder sister Wanda were always together: the latter used to help at public occasions the younger was quite shy. The sisters also helped each other in finding ways to escape from their parental control in order to go dancing, an activity they both really loved.

- Wanda and Brunilde Amodeo

Brunilde was a real sportswoman: she played swimming, tennis and basketball, took part in athletics, she skied, near Como Lake and ice skated at the same Milanese Palazzo del Ghiaccio ‘ice-rank’ where Grazia Barcellona would start her carrier, some years later, and, of course, she played football!

- The Amodeo sisters practicing ice skating at Palazzo del Ghiaccio, Milan

- The Amodeo sisters and a couple of friends (8 February 1931).

-

The Amodeo sisters skiing with some friends, in Pian Rancio (22 February 1932).

Wanda is the first from the left, Brunilde the third.

-

The Amodeo sisters skiing, with some friends, in Pian Rancio (February 1932).

Brunilde is the second from the left, Wanda the last.

Tennis, however, was the only sport in which Brunilde felt confident. She used to play frequently at the Tennis Club Elvezia, which was very close to the Amodeo’s house in Milan, in Porta Ticinese district.

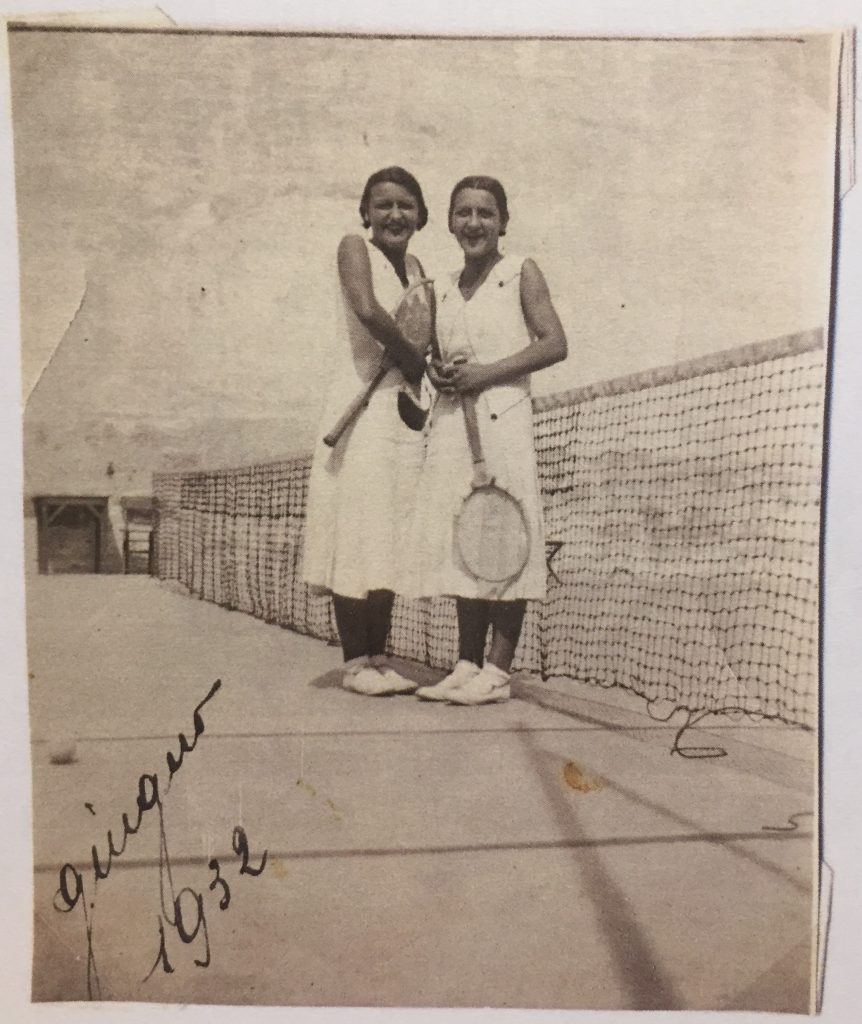

- The Amodeo sisters playing tennis (June 1932).

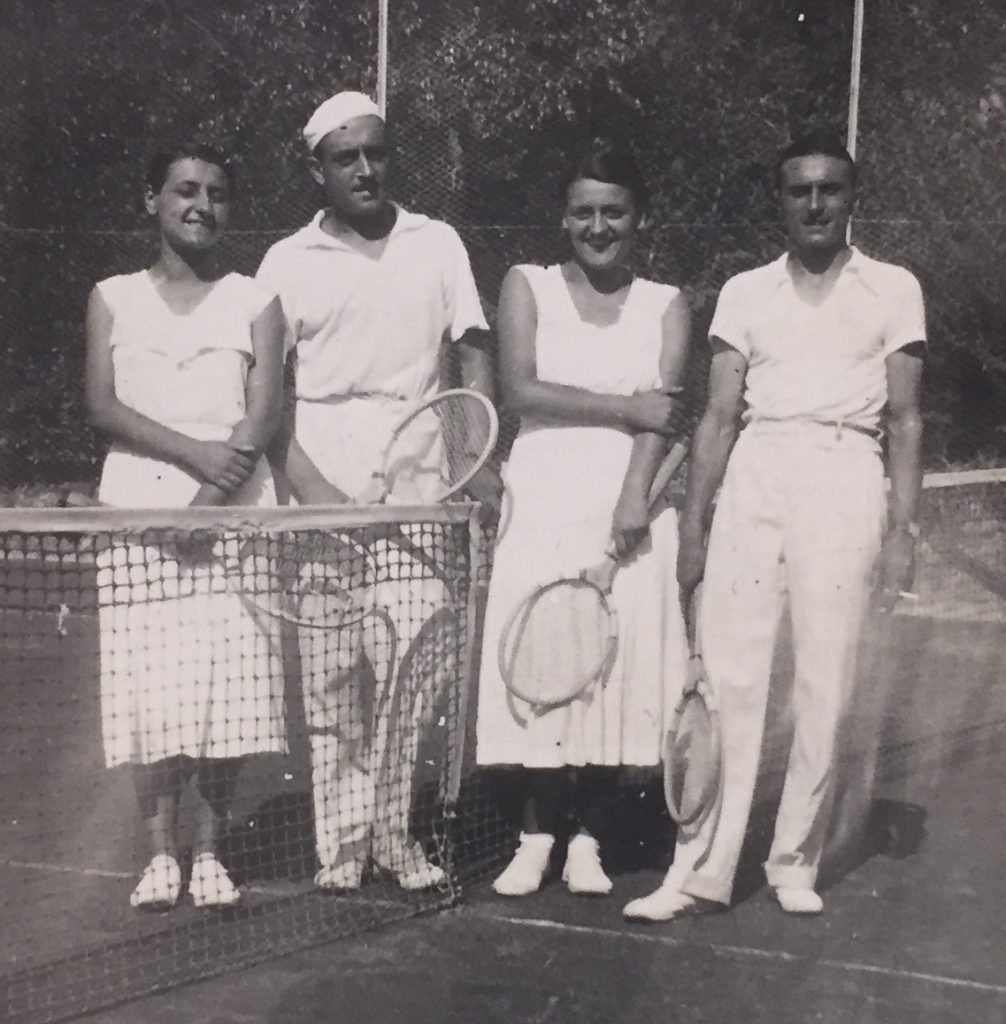

- The Amodeo sisters playing tennis doubles (1933).

-

The Amodeo sisters and some tennis players (please note the first, Japanese-like!).

The place could be Tennis Club Elvezia.

Brunilde was a supporter of FC Inter, at that time called “Ambrosiana Inter”, because of the nationalistic Fascist linguistic policy. Since her sister Wanda supported AC Milan, their older brother Bruno had a lot of fun accompanying them at the Milan derby!

-

The three couples wearing swimsuits in Lierna (Como Lake), 1937.

From the left: Bruno’s wife; Bruno Amodeo; Wanda Amodeo; Nino Caverzaschi; Brunilde Amodeo; Bianco Bracardi.

-

Wanda, Bruno and Brunilde Amodeo skiing

Pian Rancio (Monte San Primo, Como), in February 1936.

Brunilde and Bianco met at Ponzio public swimming pool in the summer of 1934, when she was 20 and he, 23. Bianco was there with Nino Caverzaschi, a colleague from the Post Office Administration, who courting Wanda. Both the couples would marry some years later. Since the very beginning, Brunilde informed Bianco that she didn’t like the bravado of the Fascist camicie nere ‘Blackshirts’.

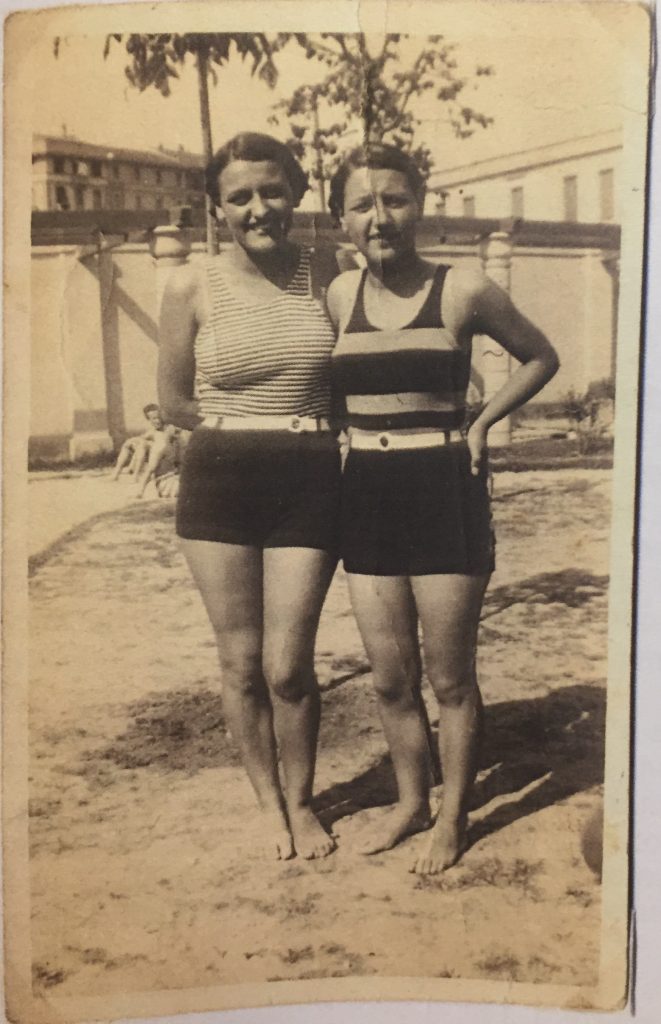

- The Amodeo sisters wearing swimsuit in a public swimming pool

Bianco left Arezzo, Tuscany when he was just 17, to look for greater opportunities offered in the huge city of Milan. He loved sports too: he practiced athletics (400 meters) in the Pro Patria sports centre, where he was a member of the successful Pro Patria relay team .

- A balding Bianco playing football with some friends.

Bianco (the last on the right in the 1st image and third from the left in the 2nd) with his rowing teammates

In Autumn 1935, the Second Italo-Ethiopian War started with both Bianco and Nino called on, they had to leave their girlfriends for some months. Later, Bianco declared that because of the war he missed the opportunity to qualify for the 1936 Summer Olympics; Nino came back from Ethiopia with a serious infection to his legs and an invalidity pension.

-

Bianco as an Italian soldier in Africa, with a local child (21 May 1935).

The war started some months later.

In the spring of 1938, Bianco and Brunilde finally get married, choosing to live in her parent’s building, in Città Studi district. She had a good salary, which allowed them to furnish their 4 rooms apartment with Bauhaus-styled furniture.

When WW2 started, Bruno was called on as a radioman by the Italian army, in Bari (Southern Italy). During his military service, Bruno came back to Milan and in February 1942 Brunilde gave birth to Brunella.

-

Brunilde & Brunilde (1942).

The low buildings in the back are the social houses for the ATM (Milan public transportation company) tram drivers

in via Beato Angelico, Città Studi district.

As soon as he heard of the upcoming Italian Armistice (1943), Bruno left Bari and reached Milan, before Italy was split in two. Because of the Allies’ bombing of Milan, the Bracardi family were displaced to live in the Pavia countryside with relatives. Each morning, Brunilde had to commute to her job in Precotto, Milan from the countryside, a very dangerous journey which sometimes included strafing in the Stazione Centrale area. Nevertheless, her salary was able to feed the combined families. Meanwhile, Bianco found a job at the Municipality of Milan Registry Office (note that during those months, former footballer Marta Boccalini was working for the Municipality too, in the Ration Card Office), organising antifascist and Jews false documents.

During the last months of WW2, Bianco found his real vocation, arranging entertainment events for the Italian soldiers, after 1945 he started to tour the country with Brunilde, Brunella and his music variety company. As a host, Bianco was surrounded by beautiful women, so Brunilde had to check carefully his husband’s activites!

After her husband’s death in 1971 Brunilde carried on taking care of the family, Francesco remembers that in her room there was a poster of FC Inter team.

- Brunilde, Bianco and Brunella (late 1940s)

As well as Brunella’s family book, Francesco himself was able to give me a lot more information about his grandmother’s beliefs. Brunilde and Wanda both received their First Communion when they were little girls, just like all the other Boccalini’s sisters, then Brunilde became an nonbeliever, while Wanda remained Catholic, as did Brunella, Brunilde’s daughter

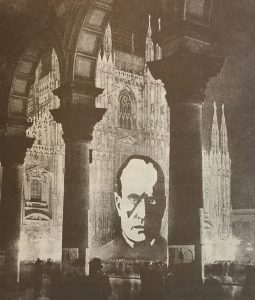

Brunilde was an avowed Communist, although she never joined the Party. Unfortunately, Francesco can’t say when exactly his grandmother became a Communist – before, during, after the war?!?: anyway, when Mussolini visited Milan in the 1930s, she never attended the mass gatherings to watch the Duce.

-

On October 28th, 1933, the Partito Nazionale Fascista (National Fascist Party) Secretary Achille Starace (the one who was suppressing women’s football in Italy) visited Milan.

During that night, the Duomo was brightly lit, and a giant Duce’s poster was posed in front of the cathedral

Source: La Rivista Illustrata del Popolo d’Italia, November 1933

Starace speaking in front of Duomo, Milan, October 28th, 1933.

Francesco, as the custodian of his mother’s archives and memories, in the form of hundreds of photos, shed further light on the life of Brunilde Amodeo.

The first group of photos are very useful in order to gain a better comprehension of the calciatrici activities: their customs, before, during and after football matches, their apparel, and the composition of their teams.

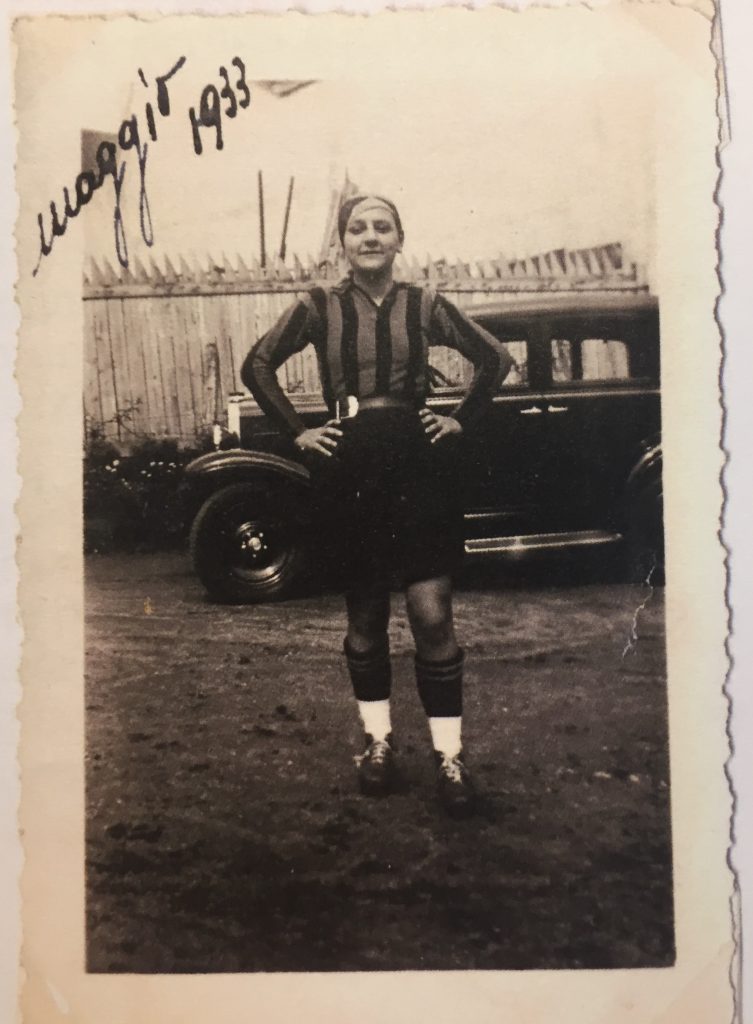

Brunilde as a footballer (May 1933). She’s wearing a black-and-blue jersey, and a belt to keep her skirt up. The fence and the black car in the background prove that this picture comes from the same photo-shoot as the Ninì Zanetti’s one, which was published by Il Calcio Illustrato on 26 July 1933. On that day, the Milanese weekly sports magazine published a group of calciatrici photos. Please see Graziella Lucchese’ picture in https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/football/brave-and-clever-calciatrici-under-the-fascist-regime-the-first-womens-football-club-in-italy-milan-1933/ ), which should be dated May, evidenced by the jerseys that are being worn.

- Ninì Zanetti is wearing the black-and-white jersey, not the CINZANO’s one she would wear later.

The same GFC group photo that Playing Pasts’ readers have seen in Part 3. Luisa Boccalini dated this picture September 1933, but Brunilde Amodeo dated it correctly as May 1933 (in fact, it was published by Il Calcio Illustrato at the end of that month). Please note the handwritten “Amodeo” on the back of the image as shown below – probably, someone in the GFC used to make some copies of the pictures, and then distributed them to each footballer.

-

The GFC “B” team, wearing garnet jerseys (April 1933).

Relying on other pictures published by newspapers, the whole line-up can be reconstructed.

Standing: Frida Marchi (wearing her typical belt!); Ester Dal Pan; Rosetta Boccalini (with white headband); Elena Cappella; Augusta Salina.

Kneeling: Wanda Dell’Orto; Brunilde Amodeo; Graziella (or Maria) Lucchese.

Seated: Losanna Strigaro; Dell’Era (male goalkeeper); Wanda Torri.

-

This photo, published by Il Calcio Illustrato on 12 April 1933 was taken from the same photo-shoot as the previous picture

Taken by Marchi, Dal Pan, Boccalini, Cappella, Salina.

In the article, the Milanese weekly sports magazine writes that during the match (played on Sunday 9 April 1933) Rosetta Boccalini, who was the best player, scored 2 goals for the black-and-white team in the first half

During the break, trainer Umberto Marrè (a previous professional footballer) changed some players

Rosetta scored another goal, akin to Dal Pan.

In the end, due to Torri’s own goal, the “A” team won 3 to 2.

As Rosetta is wearing the garnet jersey, shows this photo was taken at the end of the match.

-

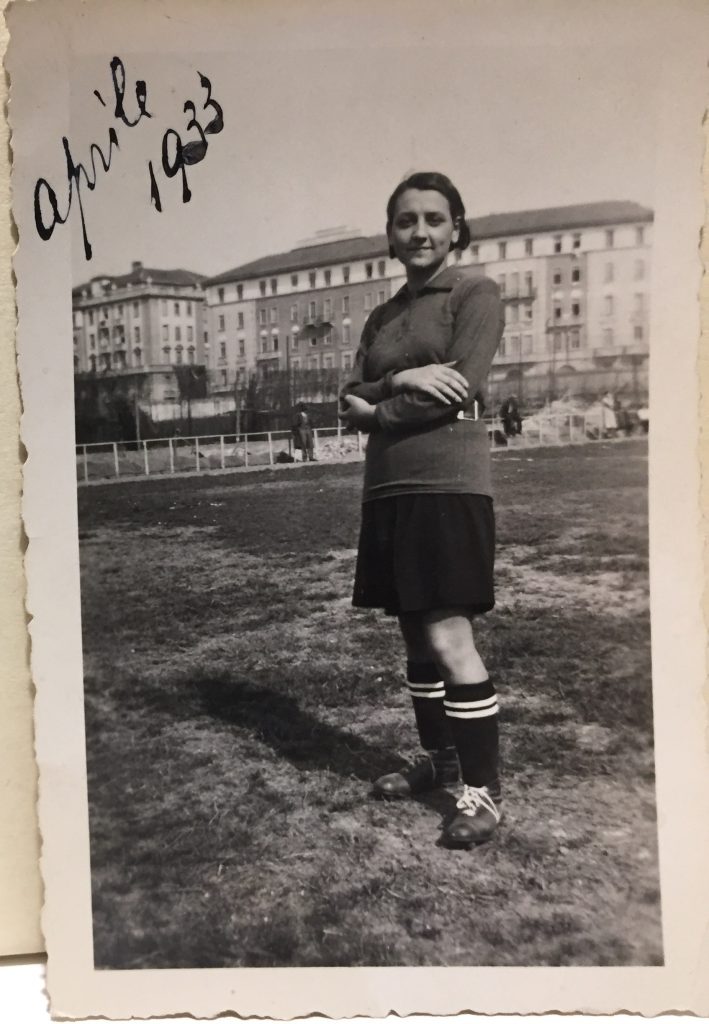

Brunilde as a footballer, in garnet jersey (April 1933).

This photo was published by Il Calcio Illustrato on 24 May 1933 issue

-

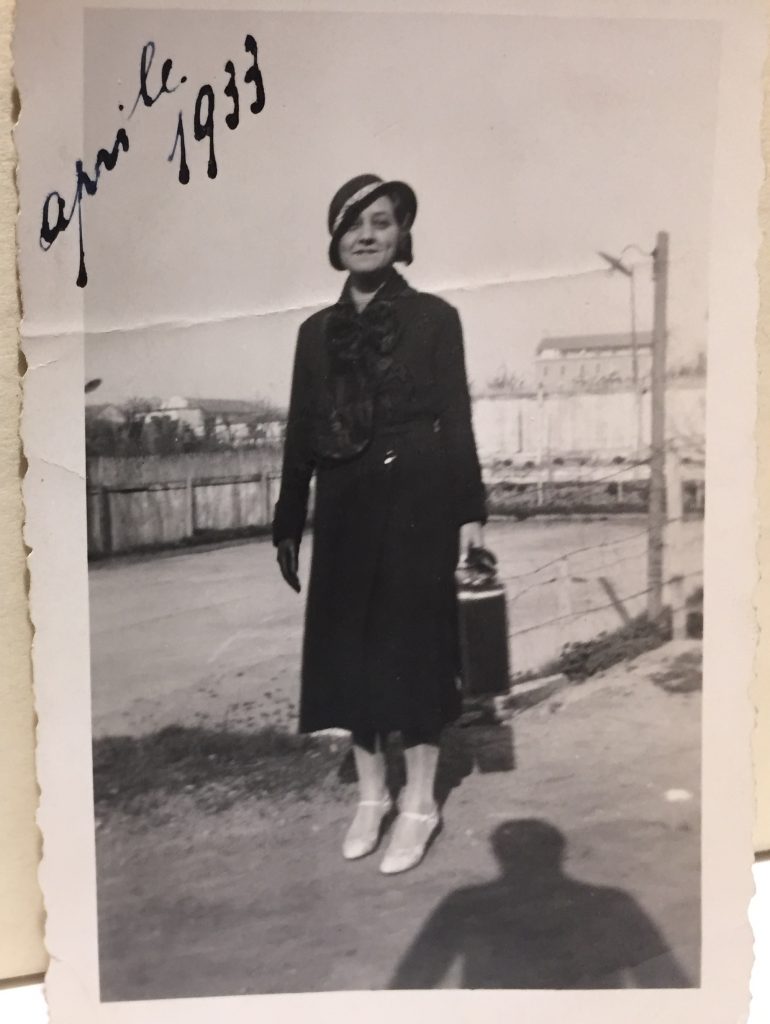

Brunilde with a suitcase.

Relying on the date and the fence on the back, it can be argued that this photo was taken before or after a GFC match:

therefore, that suitcase was used by the very elegant Milanese girl as a sport duffel bag!!!

-

Mina Bolzoni, captain of GS Cinzano, the referee & Brunilde Amodeo, captain of GS Ambrosiano (1933).

This photo is full of historical information:

1) it’s the first GFC image depicting a male referee;

2) it shows how many people attended the last public matches in Summer 1933 (newspapers reported about 1.000);

3) “TORINO” can be viewed under “CINZANO” (please see the comment on the last Marta Boccalini’s picture in Part 3);

4) Mina is wearing black socks, without the double white stripes, as we can see in the fourth last photo (CINZANO line-up) of Part 3.

-

Rosetta Boccalini kicking the ball during a GFC match.

A smaller version of this photo has been published by Il Calcio Illustrato in the 3 May 1933 issue.

Please note the small flowers on the pitch: what a meadow!

-

Brunilde the footballer, wearing a black-and-blue jersey (1 October 1933).

The photo was taken the very same day the Federal athletics instructors reached the GFC field

making the footballers run in order to rehearse their timing for a 50m race.

Other images confirm that Brunilde Amodeo and Ninì Zanetti were great friends both on and off the pitch, indeed, a journalist had once called them the GFC Siamese twins.

- Brunilde (1st from the left), Ninì Zanetti (4th) and Wanda (6th) with some friends in a swimming pool (July 1933)

-

Brunilde with some friends.

She’s the first from the right; Ninì Zanetti is the first from the left.

The girl in the first row (in white) could be calciatrice Mina Bolzoni.

The photo is dated August 1933: while the calciatrici were spending carefree holiday time together (probably in some hill/mountain village: see the background), someone in Rome was planning the repression of women’s football in Italy …

Ninì Zanetti was more than likely the link between Brunilde Amodeo and the Gruppo Sportivo Giovinezza, the new female sport society founded in 1934 by the local Fascist authorities in order to ‘convert’ the former calciatrici members in more useful athletes and basketball players. The only photo depicting Brunilde in a GS Giovinezza shirt dates to Sunday 28 October 1934. One week later, Brunilde took part in the first ever GS Giovinezza athletics meeting in Milan: the Milanese girls competed against GS Venchi-Unica from Turin, the strongest female club in Italy. Brunilde was 3rd in 100m, and in 200m (running 33’ 3/10) with Ninì Zanetti finishing 5th in 100m. We don’t know the name of the members of 4x100m relay, who recorded a good time of 45’’ 2/10, just 1/10 more than GS Venchi-Unica relay team.

-

Brunilde, the athlete representing Gruppo Sportivo Giovinezza,

at Forza e Coraggio sporting centre, Milan (28 October 1934)

Then something happened, and Brunilde suddenly stopped all her athletics activity in GS Giovinezza: sometime later, as proved by 3 photos, she joined another female club in Milan, the Dopolavoro Filotecnica, with some other GS Giovinezza girls; including Franca Agorni, who would later compete in the 1936 Summer Olympics with the Italian team. Dopolavoro Filotecnica first began as club in the Summer of 1935, becoming the most important female sports society in Milan by the late 1930s. I couldn’t find Brunilde Amodeo’s name in any newspaper report regarding the Dopolavoro Filotecnica: in all probability she joined the society just for training, or maybe her athletic performances were at such a high-level as those of Jolanda Colombo, Franca Agorni and Maria Caselli, who would later become Italian champions in their disciplines. We know that in November 1935 former calciatrici Ninì Zanetti, Ester Dal Pan and Ellera Stroppa joined the Dopolavoro Filotecnica basketball team: again, Ninì could have been the one who introduced Brunilde to this new sporting experience.

-

Filotecnica ONB athletes.

Standing: Jolanda Colombo; ?; Franca Agorni; Brunilde Amodeo.

Kneeling: Ellera Stroppa (a former GFC calciatrice), or Maria Alfero (they look very similar!); Maria Caselli.

-

Filotecnica ONB female athletes and male trainers (from the same photo-shoot as the previous picture).

Standing: Ellera Stroppa/Maria Alfero; ?; Franca Agorni; Brunilde Amodeo.

Kneeling: Jolanda Colombo; Maria Caselli.

-

Filotecnica ONB female athletes and male trainers.

Standing: male trainer; Maria Caselli; ?; Jolanda Colombo; male trainer; Franca Agorni; ?; Brunilde Amodeo; ?; Ellera Stroppa/Maria Alfero

For this reason, probably the ‘V’ team shirt, which Brunilde can be seen wearing in a lot of photos from 1935 can be identified with the Dopolavoro Filotecnica basketball team (of course, further proof is needed for this to be positively proved)

-

“V” team, with trainers (5 May 1935).

Brunilde is the third girl from the left, standing. Ellera Stroppa (or Maria Alfero?) is the second girl from the left, kneeling, Ester Dal Pan is the fourth.

-

“V” team (5 May 1935).

Standing: Franca Agorni; ?; ?; (Jolanda Colombo?); ?; Brunilde Amodeo.

Seated: Wanda Amodeo.

-

Athletes with a javelin (June 1935).

Standing: ? (with glasses); ?; Ellera Stroppa (OND Filotecnica shirt); ?; ? (wearing a former GFC black-and-blue jersey?); Brunilde Amodeo (“V” shirt).

Seated: Jolanda Colombo (“V” shirt); ? (OND Filotecnica shirt); ?.

- Brunella wearing the “V” kit (April 1935).

-

The “V” team in Pavia (27 January 1935).

Ellera Stroppa/Maria Alfero is the first from the right; Brunilde Amodeo the 6th.

Reporting on the last public GFC match in July 1933, the La Gazzetta dello Sport journalist wrote that Brunilde Amodeo (GS Ambrosiano, in black-and-blue striped shirts) primeggiava ‘excelled’ in the middle of the pitch, while opposing the GS Cinzano central halfback, Wanda Dell’Orto. During the match, Brunilde initiated the play that ‘gave wings” to the centre forward schoolgirl Rosetta Boccalini, the Meazza of women’s football, who scored the first goal for the Inter team, with an unstoppable shot. After so may years, another chapter has been added to the incredible hidden history of GFC: with Brunilde still proving herself useful in assisting her teammate Rosetta …

-

Some GFC players, wearing the black-and-blue jersey (May 1933).

Standing: Elena Cappella, Brunilde Amodeo, Rosetta Boccalini.

Seated: Ester Dal Pan.

Article © Marco Giani

To read Part 7 – Click HERE

For the Italian interview to Francesco Bacigalupo about Brunilde Amodeo (containing more historical data about the life of this calciatrice), see:

https://www.academia.edu/41953300/Intervista_a_Francesco_Bacigalupo_10.02.2020_

![“And then we were boycotted” <br> New discoveries about the birth of women’s football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 6](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/PP-banner-maker-4.jpg)