Introduction

In 2020, Alexandra Park, in southern Manchester, celebrates 150 years since its opening. During its inauguration, the park was acclaimed by the Mayor of Manchester, John Grave, as a ‘park of the people. The people have made it; the people have paid for it; and the people will use it.’[1] This was not just a space to escape everyday life, but somewhere with a greater social purpose. The Mayor continued:

‘[the] muscle which institutions like the park will aid in developing represents that kind of “armed neutrality” which is so well understood and appreciated in Europe, and which has heretofore given to Great Britain the place which she has fairly earned in the service of civilisation.’[2]

During the opening months of the Franco-Prussian war, this paean to the park as a promoter of British national security, imperial expansion and civilisation was explicit. This was not unique to Manchester and the development of public parks in Britain was not just about providing pleasant walks or grounds to play, but was embedded in the politics, society and cultures of the Victorian period; parks were a spatial reaction to the problems in fast-growing urban industrial environments and the bodies they produced. Just like the people who used these parks, the new spaces were never neutral – they were shaped by and shaped their users. These new urban spaces became focal points for new city cultures, reproducing, constructing and challenging them in different ways through time. Historian Carole O’Reilly has highlighted this, noting that the meaning and role of parks changed from the Victorian to the Edwardian period. In the Victorian period, ideas of social control inherent in concepts of ‘rational recreation’ abounded, while in the Edwardian period new forms of urban identity and attachment were formed by spontaneous games, unintended uses and political meetings.[3] The meanings and purposes of public parks in different locations, in different times, and for different people across the world have also changed. In this introductory article for the special section to celebrate 150 years of Manchester’s Alexandra Park, I will look at the how the concept of the need for urban spaces, which was recognised before Queen Victoria’s reign, quickly developed to play a fundamental role in urban life by the time of Alexandra Park’s opening in 1870. Beyond history, I hope this will help you think about how your local park has contributed to the cultures and societies around you and ask you to contribute to this new Playing Pasts Section via contact@playingpasts.co.uk.

-

Alexandra Park Promenade, Manchester.

Source: briangeorge1945 – Wikimedia Commons

Collect, regulate and improve: Rational Recreation and the 1833 Public Walks and Open Spaces Report

Towards the mid part of the 19th century, changes in British society attracted more attention from statisticians, scientists and demographers. As Asa Briggs highlights, this accumulation of knowledge about society was not a purely scientific exercise, but was linked to concerns about economics, society, and morality. In 1834, the Manchester Statistical Society heard a report into cotton trade workers and beyond the statistical data collected the report focused on health, education, wages, child cruelty and morality. Similar research was conducted in other places in the mid-nineteenth century, as statistical knowledge and attempts to quantify the world were seen as guides to form new laws, to educate and, perhaps, to achieve social, cultural and economic progress.[4]

From the 1830s, concerns about the conditions of the workers saw an increasing number of people look towards, what became known as, ‘rational recreation’ as a solution. Hugh Cunningham notes that from the late-1820s, the leisure-patterns of the wealthier parts of society were considered by some social reformers as a solution to urban problems. Partly out of a desire to control, but also from a sense of guilt at the lack of opportunities afforded to the majority of urban citizens, rational recreation would provide social, educational and moral improvement. Exactly what this ‘rational recreation’ meant was contested and hotly debated and while there was no consolidated movement, the need to improve the non-working urban experience became an important part of social discourse in the 1830s.[5]

In 1833, a Select Committee, chaired by Robert Slaney MP, demonstrated the links between data, rational recreation, and social reform and progress. The Select Committee on Public Walks was formed to promote the ‘Health and Comfort of the Inhabitants’ of populous towns by securing open spaces to be used as ‘Public Walks and Places of Exercise’.[6] Following reams of evidence, data and opinion, – which Cunningham suggests was intended to paint a deliberately bleak picture[7] – the report’s conclusions were clear. 50 years of industrial expansion, property price increases and urban enclosures, had not taken account of the need, particularly amongst the ‘middle or humbler classes’, for spaces to walk, exercise or entertain themselves; providing such spaces would augment the ‘comfort, health and content’ of these classes.[8] Manchester and the surrounding cotton towns of Salford, Bolton, Wigan, Blackburn and Bury were singled out at the start of the report. While they had made tremendous strides in ‘Wealth, Importance and Population…no adequate provision has been made for Public Walks, or any reservations of Open Spaces giving facilities for future improvement.’[9] The same was said for other manufacturing centres in the Midlands and Yorkshire. In other provincial towns, where provision had been made, it was far behind the needs of the rapidly expanding population. Only in parts of London was there said to be sufficient space for all classes to walk, yet here too, geographical and economic variants played a part, with no facilities laid out in the east and the river not utilised as it was in Paris, Florence or Lyon.[10]

Taken as a whole, the report outlined that Britain needed open spaces and public walks; if this did not happen, then physical health and, perhaps more importantly, social morality would disintegrate. Without spaces to walk, the working classes would only have access to pubs and drinking dens, whereas with such spaces a new man would emerge:

‘a man walking out with his family among his neighbours of different ranks will naturally be desirous to be properly clothed and that his Wife and Children should be also…it is by inducement alone that active, persevering and willing industry is promoted; and what inducement can be more powerful to any one, than the desire of improving the condition and comfort of his family.’[11]

To do this, a change in law was needed to regulate the use of urban space and money had to be raised by private individuals, subscription, or, if needed, the State.[12] Despite their strident views, the Select Committee probably knew the government was unlikely to follow the recommendations and in the 1830s, only piecemeal legislation was enacted.[13] However, open spaces and public walks seemed to be a data-driven spatial solution to the problems caused by rapid industrial expansion and one which fused together the increasingly vocal (if not always popular) political, social and cultural ideas of the time. These ideas linked to the optimistic paternalistic Utilitarian desires to provide the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people, and more pessimistic views from the 1830s and 1840s, which saw the increasing number of urban and newly urban poor as breading grounds for barbarism and revolution.[14] By the mid-nineteenth century, concerns about the ‘Condition of England’ as Thomas Carlyle put it, could be found as a foreboding literary theme in the works of Disraeli, Gaskell and Dickens.[15] The 1833 report, while only producing recommendations not legislation, was the epitome of a mid-19th century need to collect data and propose changes that would force society to improve physically, educationally, economically and morally. These ideas would be the basis for the emergence of the “people’s parks”, yet what was clear was that it was up to those with money and authority to decide where, when and how, the ‘people’ would use their leisure time and what form it would take.

Opening up Open Spaces

Garden Historian Frank Clarke notes that the Slaney Report of 1833 and others in the 1830s and 1840s demonstrated the growing concern at the conditions in industrial towns and, in particular, the stark contrast between the bucolic imagery of the British countryside and its impoverished, urban factory-riddled landscapes. For the many farmhands, country labourers, and rural workers who moved to the expanding cities attracted by regular work and wages, the contrast must have been acutely felt.[16] Bringing the countryside to the city in the form of urban green spaces was seen as one way to alleviate these problems. Of equal concern was that existing spaces of popular recreation, in the guise of commercially run pleasure-gardens and pubs, were seen by rational recreationalists as dens of virtue, flirtation and vulgarity;[17] as enjoyable as this was, it was not the morally uplifting leisure-time that they sought and that the people needed. An 1840 Select Committee on the Health of Towns, highlighted the anxieties that this new urban life brought, indicating that change was essential ‘not less for welfare of the poor than the safety of property and the security of the rich.’[18] Thus, in addition to the genuine concern for the poor, there was, as Hillary Taylor outlines, a self-interest and fear among the wealthy, which was part of the ‘cocktail of motives’ for urban greenery.[19] Some land-owners no doubt enjoyed the financial benefits beautiful green spaces gave to local house prices and in expanding cities the desire to provide better facilities than other localities also made parks an important element of civic pride.[20] This cocktail was a heady mix; its key ingredients were a quest for public health, moral rectitude, aesthetic beauty, financial improvement and social cohesion.[21]

-

A view of Ranelagh Gardens with ‘The Chinese House’ and ‘Rotunda’, London.

Engraved by T Bowles, 1754.

Places like this became very popular entertainment locations in the late-eighteenth and nineteenth century.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

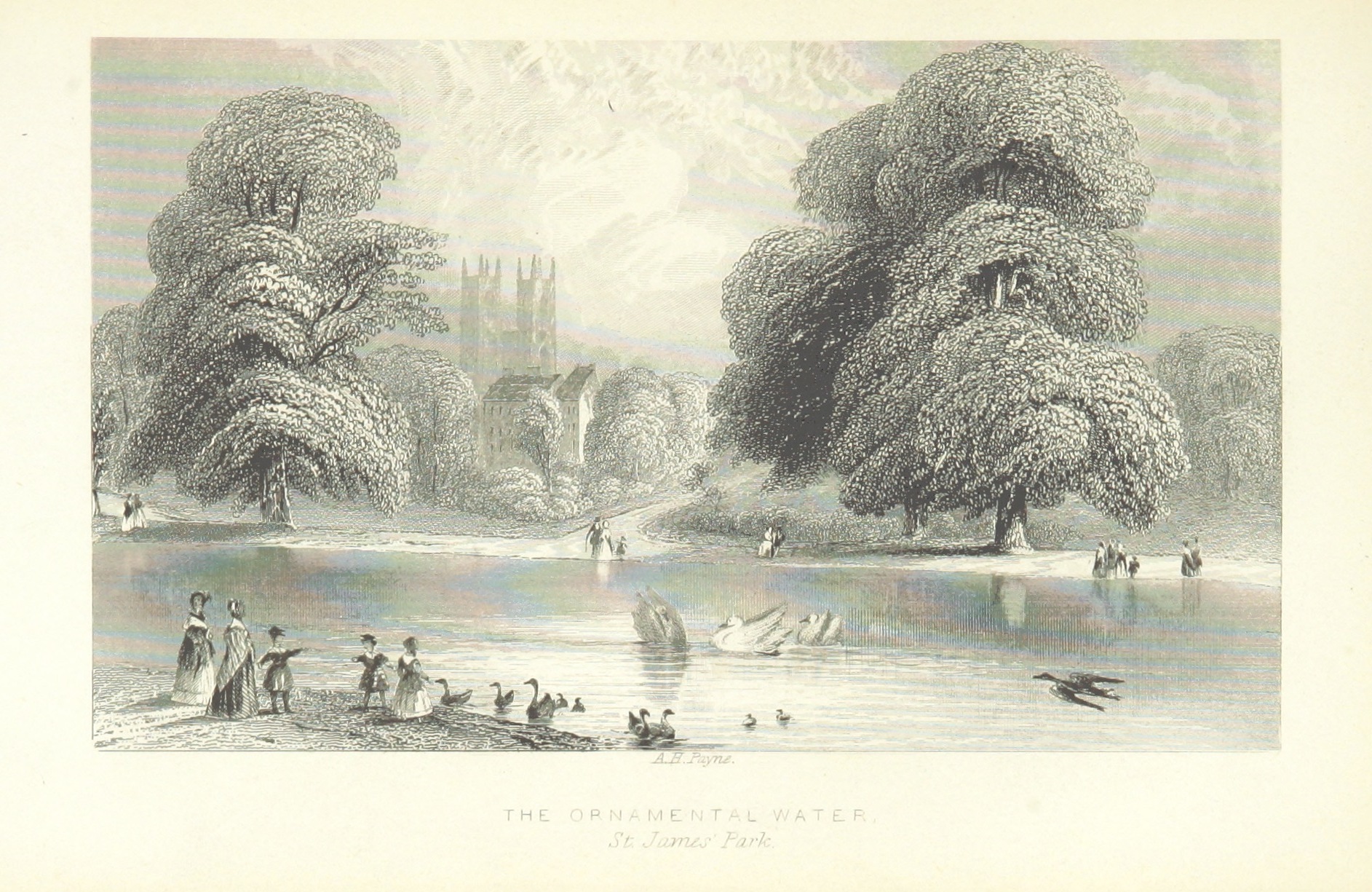

One can see that this intoxicating mix did translate into greater provision of urban greenery in some locations. In West London, as the 1833 report noted, the public had good access to a number of open spaces. In common with other European capitals, London boasted aristocratic lands, often used for hunting, which could be transformed for more popular pursuits. Hyde Park was the earliest to ‘combine the elite pleasures of walking and riding with more popular recreational use’.[22] By the late 1830s and early 1840s, the clamour for public spaces saw access granted to other Royal Parks – St James’s Park, Kensington Gardens, Green Park and The Regent’s Park.[23] In 1845, Victoria Park opened after years of local lobbying as another Royal Park.[24] Such largescale transformations in access to urban spaces reflected a counter-tide to the emergence of small, private gardens attached to new wealthy housing developments that became popular at the end of the 18th century.[25] Slowly, urban greenery was become more accessible to ‘the people’, if not owned by them.

-

The Ornamental Water, St James’s Park’, 1846, A.H. Payne

Source: British Library Flickr

-

‘A Scene in Kensington Gardens or Fashions and Frights of 1829’,

Source: Cruickshank: from British Library Flickr;

In London, Royal Parks like Kensington Gardens were opened up to the general public in the 1830s, providing the capital with a large amount of open space.

As envisaged by the 1833 report, the role of aristocratic, or at least wealthy, landowners, was important in providing open spaces for public use in the 1840s and 50s. Claimed as ‘Britain’s first public park’[26], the Derby Arboretum, opened in 1840 and was commissioned and donated by local textile manufacturer Joseph Strutt. It was designed by celebrated landscape architect J.C. Louden, who believed arboreta were alternatives to exclusive private gardens, and he imbued it with his particular philosophical concepts.[27] However, the image of a ‘public park’ as we may imagine it today, needs to be tempered somewhat. As Elliot, Watkins and Daniels have shown, while the Derby Arboretum had free entry for two days in the week, which certainly encouraged attendance by poorer citizens:

‘in remaining primarily a subscription-based institution and promoting an image of rational, objective science and appropriate reflective and respectful conduct and behaviour, Derby and other public arboretums helped to differentiate and shape Victorian middle-class identity.’[28]

Those who entered the arboretum were to be seduced by the Victorian combination of science, education, and morality – the proliferation of glasshouses in public parks in the second half of the 19th century (including Alexandra Park) was a testament to this desire to present the natural world and give everyone the opportunity to study and learn.[29] The public space was not an escape from perceived class difference, but a way to reinforce certain differences and, hopefully, changes others. Loudon’s arboretum, if not really a public park, would prove to be a great inspiration for those in Manchester, Birkenhead and other northern towns who desired to create truly public parks.[30] Similar social and cultural ideas would be incorporated in these places too.

-

A View of Derby Arboretum c. 1900.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Legislation, Public Health, Public Order and Public Parks

In 1848, the British parliament passed a significant piece of legislation and, in the words of Elizabeth Fee and Theodore Brown, one of the ‘great milestones in public health history.’[31] Influenced by reports, social reformers, including Edgar Chadwick’s economically motivated ideas, and outbreaks of Cholera, The Public Health Act, 1848 provided a framework, including financial powers for local authorities to take charge of local health and made it clear that the health of the population was now an issue of political, economic and social importance; and so too were green spaces. Article 74 gave local authorities the power to ‘provide, maintain, lay out, plant, and improve Premises for the Purpose of being used as public Walks or Pleasure Grounds’ which permitted localities to financially support such schemes.[32] Changes in legislation were important. In 1843, the Birkenhead Improvement Committee was given permission by an Act of Parliament to borrow money to purchase land to create a public park.[33] This Act allowed the loan to be offset against rates and in 1847, Birkenhead opened one of the first fully publicly accessible parks, designed by noted landscape architect Joseph Paxton. Extra land not needed for the park was used to build new properties bringing financial benefits to the scheme.[34] In 1845, The General Inclosure Act, made provisions for land to be set aside for recreational purposes within set distances of key urban settlements. In 1847, previous local legislation was consolidated by The Town Improvement Act, making it easier for localities to purchase land for parks and other amenities.[35] The government also allocated money for new recreational spaces and in 1840, £10,000 was put aside for park provision.[36] Such Acts provided the financial and legal means for parks to be constructed with municipal funds and were linked to the increasing importance of green spaces in political, cultural and social discourses.

In the 1850s and 1860s, numerous parks opened in British cities, capitalising both on the opportunities provided by legislation and the cultural desires of the Victorian age. As Taylor outlines, the public parks became spatial metaphors for this age. Concerned with health, but just as concerned with order and personal enlightenment, such places were the spatial representation of an ‘ideal and rational society, a society which combined the order and civility of the polite urban community with the scientific detail, managed beauty and spiritual resonance of the native countryside’[37] Such spaces were not neutral spaces of leisure but ways for Victorian society to construct and reproduce the dominant cultural discourses of the age and to order itself accordingly; to quote Taylor again, parks were ‘gigantic stage-sets, in which the design facilitated the appropriate comportment and responses of the players.’[38] Before 1870, the stage was constructed for the people, not by the people, and it was a stage that was often bereft of games and sports; ensuring that rowdy pastimes were kept to a minimum was more important than bowing to the prevailing trends.[39]

Alexandra Park and Manchester’s Parks

-

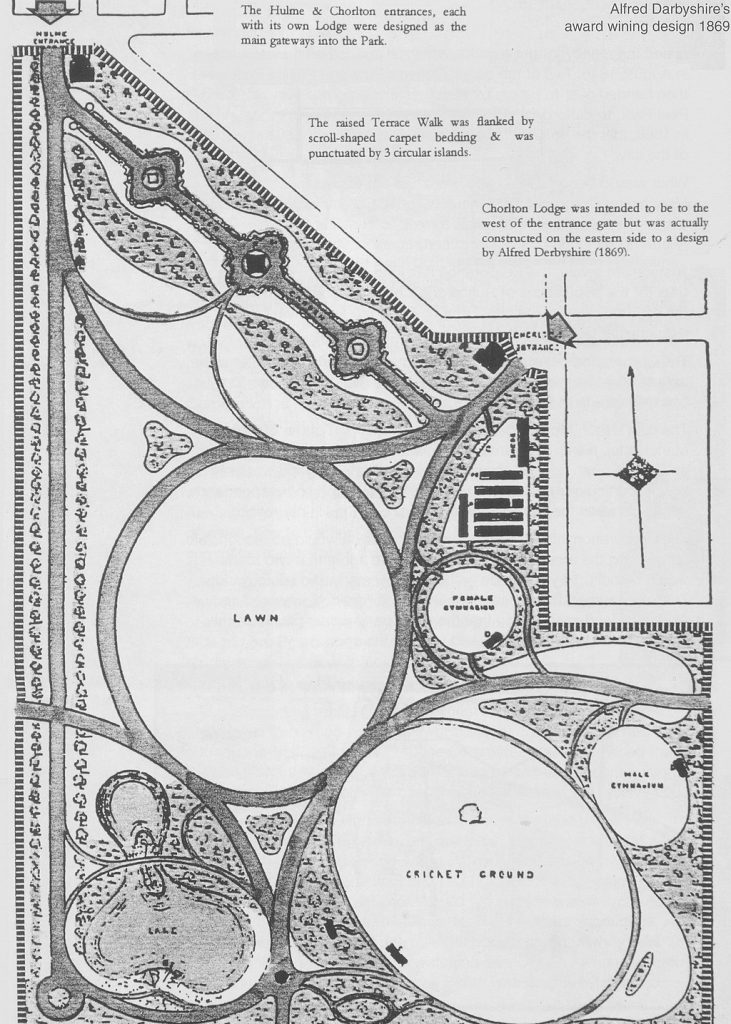

Alfred Darbyshire’s design for Alexandra Park, Manchester from early 1869.

Although Mr Hennell’s plan won the tender, this design indicates the desire for recreational spaces.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Opening in 1870, Alexandra Park did include spaces for recreation from the outset. In 1869, Mr Hennell won the prize to design the park including large lawns and a cricket pitch.[40] Perhaps, wary of disturbing order, or more importantly the intricate bedding plants and young grass, cricket was prohibited in the early years of the park, despite the increasing popularity of sport in Moss Side and South Manchester.[41] Other areas of sedate recreation were also provided in the form of bowling greens and playgrounds for children. Unlike other parks in Manchester, Alexandra Park was funded by Manchester ratepayers. And unlike other Manchester parks, it wasn’t in Manchester. Although it followed the pattern of many Victorian “People’s Parks”, in this respect at least, it seemed to be different.

The concepts behind the park showed how much change had occurred both conceptually and spatially. In 1833, Slaney’s Select Committee heard that there were only 3 spaces that the Mancunian public had any access to; Ardwick Green, the Infirmary Gardens and Beswick reservoir paths. In 1840, a letter from Mr Robertson noted that in Manchester there was ‘no public park, or other ground where the population can walk and breathe the fresh air’ and that in this respect it was, perhaps, more ‘disgracefully defective…than any town in the empire.’[42] Spaces for games were in the hands of private clubs too. What time there was for recreation was spatially limited to the streets or private entertainment ventures.[43] While rational recreationists saw these as dangerous, Emma Griffith points out the lively cultural scene was prized by Manchester’s workers living in what Fredrich Engels described as ‘hell on earth’.[44] Calls for change in Manchester and demands for open spaces grew, but they also revealed the geographical divide between London and elsewhere. While the government had spent great sums of public money on the capital’s urban spaces – including £20,236 to buy Primrose Hill from Eton College in 1842; £104,903 to purchase Battersea Park in 1846 (and another loan of £200,000 for this site) and a grant of £115,683 from the Commission of Woods and Forests towards a park in the East End – other locations saw less financial outlay. Of the £10,000 granted in 1840 for park provision, only £8,037 had been spent by 1858 – of which £3,000 in Manchester.[45] Before the 1860s, for those who lived beyond the government’s glare in London, it was down to philanthropists, wealthy private individuals, or public subscription to give them access to parks.

In Manchester, it was local MP Mark Phillips who pushed the need for green spaces. Echoing the calls of contemporaries, he highlighted the positive effect of green spaces in urban environments noting that they would act as ‘lungs to the inhabitants of densely populated areas’.[46] Following an effective local subscription campaign, Phillips and prominent local citizens put forward £32,000 towards purchasing land and developing these new green lungs. In 1846, Peel, Phillips and Queen’s Park opened providing the opportunity for a range of walks, games and recreational opportunities for Manchester’s population. Upon opening, the three parks were handed to their respective local municipalities to be maintained.[47] However, the notion that green spaces automatically provided healthy surroundings became challenged by the 1860s, as the pollution from Manchester’s industrial centre began to threaten the trees in both parks.[48] Yet, morally, some claimed they were working. In 1854, it was observed that in Manchester, instead of spending Sundays in pubs and participating in street-games, dog fighting and loitering, in the local parks workers were being ‘induced to dress better for the purpose of appearing in those parks.’[49] Undercutting this cornerstone of rational recreation , Cunningham highlights that other contemporaries observed people ‘drifting ‘from the park to the pub.’[50] Whether they replaced drinking and other ‘vices’ or merely supplemented them, the parks were becoming an increasingly important part of leisure culture in the great Cottonopolis.

-

Manchester from Kersal Moor, by William Wylde, c. 1850s.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Despite public use of these parks, the privately created parks of the 1840s suggested that Manchester was in danger of succumbing to a mid-19th century spatial paradox common in other cities; while land was increasingly demanded for public space, existing public spaces were being sold to private companies and landowners, placing a greater burden on private provision for public recreation.[51] In combination with this, there was a dramatic population increase; around 1800, Manchester had a population of 89,000, this doubled by 1820 and in 1851 stood at around 400,000.[52] Though Parliamentary Acts and funds could clear the way to provide recreational spaces for the city’s inhabitants, if they were not used, then this expanding population would have to rely on private provision. Yet Manchester had an advantage that other cities did not. Without a resident aristocracy, the Manchester council was in a good place to offer public services for citizens without interference from a wealthy and established local clique.[53] As land-prices increased and space became swallowed up by Manchester’s industrial explosion, the corporation had to balance the need for public spaces against its own lack of available space and desire to progress economically; the solution lay to the south in Moss Side and Whalley Range where the urban met the rural.

-

William Tatton Egerton, 1st Baron Egerton of Tatton by Frederick Sargent.

Source: By kind permission of The National Portrait Gallery, London. Information: pencil, circa 1870s-1883, NPG 5646

There, a 60-acre site was purchased from Lord Egerton in 1868 for £400 per acre.[54] This site would become the location for Manchester’s first large park funded by the corporation and rate-payers rather than by private initiative; both the area around it and the park itself would carry the name of Alexandra, the Princess of Wales. Such monarchical links were perhaps an overt attempt to raise the social profile of the parks and were common across Britain.[55] Unfortunately, for those wishing to aggrandise Manchester and their illustrious monarch, the name ‘Victoria Park’ had been taken for an exclusive residential development in the 1830s.[56] While the new spaces could be sources of civic pride, there was also a danger that large, grandiose, expensive parks forgot the needs of their users.[57] In the case of Alexandra Park, for all the mayor’s initial exultation, its location outside the boundaries of the corporation, far from the centre and city’s poorest, as well as its cost, was a cause of debate and criticism later in the century. In 1884, Councillor Asquith, described it as ‘one of the greatest mistakes the Manchester Corporation ever made’.[58]

However, such negative pronouncements were a long way away from the exuberant atmosphere surrounding the opening of the park in 1870. Echoing the Select Committee report from 1833, the Mayor praised the park for improving ‘not only the comfort but also the health of the people.’[59] In addition to health and comfort, Alexandra Park had ‘a stronger moral flavour’ than other Manchester parks. [60] Yes, it had spaces for recreation, but they were tightly controlled and regulated. Playgrounds (called Gymnasia) were provided for children; however, girls and boys were kept separate reinforcing the gendered nature of public spaces.[61] This can be seen as an example of what Vertinsky outlines as the nineteenth century’s use of sporting and leisure spaces to define and construct concepts of women’s bodies and their place in society, usually littered with ideas of frailty, weakness and duty.[62] Women and men were to be kept separate and to have different corporeal experiences of the city. The park was a place to reproduce such gendered discourses and to further cement them in the urban landscape. The long-terraced walkway was also morally clear providing a location for a fine walk in the correct clothes. In the Victorian imagination such places helped to ‘defend and define public behaviour’.[63] If Alexandra Park was a space provided for public enjoyment, it was also a space that ensured the public could be stopped from enjoying the ‘wrong’ things. Music was banned until 1884 and popular entertainments in the park were often required to be closed on Sunday to observe religious norms.[64] Thus, on the sole day for recreation for most of Manchester’s workers, opportunities for enjoyment were curtailed within the strict, formal lines authorised by the council and prevailing culture. Alexandra Park may have been, as the Mayor claimed in the summer of 1870, a “People’s Park”; however, its role was not to encourage joyful exuberance but to act as a transitional space where those who entered would be made healthy, educated and socially responsible citizens.

-

A Photo of Alexandra Park, Manchester c. 1891

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The End of an Introduction: Power, Parks and People

This introduction to public parks has focused on the importance of parks in the political, social and cultural life of Britain and its industrial cities. They were, and are, places where different powers are contested and rooted into the ground. As with all spaces, they are not neutral, they are shaped by and shape us. I have tried to show that the notion of the “People’s Park” needs to be questioned. It is a simple term which suggests belonging, ownership and opportunity and yet, at the same time, it was one which was fundamentally connected to social control over the masses and the need for new, healthy, and morally correct bodies.

Ironically, what this introduction lacks is people. These parks were used by people, enjoyed by people and became important (and sometimes unimportant) parts of everyday life. Parks are not only theoretical, conceptual or historical spaces, but are places with immense personal and emotional significance. As O’Reilly suggests, the meaning and role of parks in society and culture changes through time – this is also true for their meaning to individuals. I hope that this special section on Alexandra Park, Manchester will provide the opportunity for those who have used the park to share their memories, their histories and their thoughts on what it means to them and what it may have meant to others. Beyond this, I hope it will provide a space for many others to think about how their local parks, green spaces, and sites of recreation have been important through time both in Manchester, Britain and further afield.

Article © Nick Piercey, Alexandra Park Research Team

References

[1] Mayor of Manchester (John Grave) quoted in ‘Opening of the Alexandra Park’, The Manchester Times, 13 August 1870, p. 7.

[2] Mayor of Manchester (John Grave) quoted in ‘Opening of the Alexandra Park’, The Manchester Times, 13 August 1870, p. 7.

[3] Carole O’Reilly, ‘From ‘the people’ to “the citizen”: the emergence of the Edwardian municipal park in Manchester, 1902–1912’, Urban History, 40:1, 2013, pp. 136-155, (p. 154).

[4] Asa Briggs, ‘The Victorian City: Quantity and Quality’, Victorian Studies, 11:2, 1968, pp. 711-730, (pp. 713-715).

[5] Hugh Cunningham, Leisure in the Industrial Revolution, c. 1780-c. 1880, (Abingdon: Routledge, 2016), pp. 91-92.

[6] Report from the Select Committee on Public Walks; with the minutes of Evidence taken before them, UK Parliament, 1833, p. 3.

[7] Hugh Cunningham, Leisure in the Industrial Revolution, p. 92.

[8] Select Committee on Public Walks, 1833, p. 3.

[9] Select Committee on Public Walks, 1833, p. 4.

[10] Select Committee on Public Walks, 1833, pp. 4-8.

[11] Select Committee on Public Walks, 1833, p. 9.

[12] Select Committee on Public Walks, 1833, pp. 3-11.

[13] Hugh Cunningham, Leisure in the Industrial Revolution, p. 93.

[14] Hillary A. Taylor, ‘Urban Public Parks, 1840-1900: Design and Meaning’, Garden History, 23:2, 1995, pp. 201-221, (p. 202).

[15] Emma Griffin, ‘Manchester in the 19th Century’ , The British Library, Discovering Literature: Romantics and Victorians, https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/manchester-in-the-19th-century [accessed 23 April 2020].

[16] Frank Clarke, ‘Nineteenth-Century Public Parks from 1830’, Garden History, 1:3, 1973, pp. 31-41, (pp. 31-34).

[17] Hugh Cunningham, Leisure in the Industrial Revolution, p. 95.

[18] Report from the Select Committee on the Health of Towns; together with the minutes evidence taken before them, and an appendix, and index, UK Parliament, 1840, p. xiv-xv.

[19] Hillary A. Taylor, ‘Urban Public Parks, 1840-1900’, p. 202.

[20] Hugh Cunningham, Leisure in the Industrial Revolution, pp.94-94; Carole O’Reilly, ‘From ‘the people’ to “the citizen”’, p. 137.

[21] See: Nan Hesse Dreher, Public Parks in Urban Britain, 1870-1920: Creating a New Public Culture, Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations, 2673, 1993, pp. 29-43.

[22] David A. Reeder, ‘London and Green Space, 1850-2000: An Introduction’ in Peter Clark (ed.), The European City and Green Space: London, Stockholm, Helsinki and St Petersburg, 1850-2000, (Aldershot; Ashgate, 2006), pp. 30-40, (p. 30).

[23] Frank Clarke, ‘Nineteenth-Century Public Parks from 1830’, p. 31. These parks remain owned today by the Crown under the responsibility of the Secretary of State of DCMS, managed by the Parks Charity. The Crown Lands 1851 Act transferred management responsibility from the monarch to the government. Please see: https://www.royalparks.org.uk/about-us/who-we-are [accessed 23 April 2020]; https://www.royalparks.org.uk/about-us/what-we-do [accessed 23 April 2020]

[24] Nan Hesse Dreher, Public Parks in Urban Britain, p. 57.

[25] David A. Reeder, ‘London and Green Space, 1850-2000’, p. 30.

[26] See the Derby Parks ‘Derby Arboretum’ webpage: https://www.inderby.org.uk/parks/derbys-parks-and-open-spaces/derby-arboretum/ [accessed 23 April 2020].

[27] Paul Elliott, Charles Watkins and Stephen Daniels, “Combining Science with Recreation and Pleasure’: Cultural Geographies of Nineteenth-Century Arboretums’, Garden History, 35: Supplement, 2007, pp. 6-27, (p. 20).

[28] Paul Elliott, Charles Watkins and Stephen Daniels, “Combining Science with Recreation and Pleasure’, p. 21.

[29] Hillary A. Taylor, ‘Urban Public Parks, 1840-1900’, p. 208.

[30] Paul Elliott, Charles Watkins and Stephen Daniels, “Combining Science with Recreation and Pleasure’, p. 21.

[31] Elizabeth Fee and Theodore M. Brown, ‘The Public Health Act of 1848’, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 83:11, November 2005, pp. 866-867, (p.866).

[32] An Act for promoting the Public Heath, UK Parliament, 31 August 1848, Article LXXIV, p. 755.

[33] See Birkenhead Park website: https://www.birkenheadpark1847.com/park-at-war [accessed 23 April 2020].

[34] Hillary A. Taylor, ‘Urban Public Parks, 1840-1900’, p. 203.

[35] See Katrina Navickas, A History of Public Space website: http://historyofpublicspace.uk/themap/timeline/ [accessed 23 April 2020].

[36] Hugh Cunningham, Leisure in the Industrial Revolution, p. 93.

[37] Hillary A. Taylor, ‘Urban Public Parks, 1840-1900’, p. 204.

[38] Hillary A. Taylor, ‘Urban Public Parks, 1840-1900’, p. 211.

[39] Hillary A. Taylor, ‘Urban Public Parks, 1840-1900’, p. 215.

[40] ‘The Proposed Alexandra Park’, The Manchester Guardian, 25 March 1869, p. 5.

[41] ‘The Alexandra Park’, The Manchester Times, 04 June 1870, p. 5; Manchester, Manchester Archives (MA), GB127, Council Minutes, Parks and Cemeteries Committee, Volume 1: 12 May 1860-25 Oct 1872, Entry 17 February 1871, p. 321; MA, GB127, Council Minutes, Parks and Cemeteries Committee, Volume 1: 12 May 1860-25 Oct 1872, Entry 12 April 1872, p. 509.

[42] Report from the Select Committee on the Health of Towns, UK Parliament, 1840, p. x.

[43] C. Latimer, Parks for the People: Manchester and its Parks 1846-1926, (Manchester: Manchester City Art Galleries, 1987), p. 7.

[44] Emma Griffin, ‘Manchester in the 19th Century’ , https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/manchester-in-the-19th-century [accessed 23 April 2020].

[45] Hugh Cunningham, Leisure in the Industrial Revolution, pp. 93-94.

[46] C. Latimer, Parks for the People: Manchester and its Parks 1846-1926, p. 7.

[47] Alexandra Park Heritage Group, Alexandra Park Manchester: a park for the people since 1870: the evolving history of a public urban space and its recreational use, (Manchester: The Alexandra Park Heritage Group, 2017), pp. 8-10.

[48] C. Latimer, Parks for the People: Manchester and its Parks 1846-1926, pp. 8-11.

[49] Quoted in Hugh Cunningham, Leisure in the Industrial Revolution, p. 95.

[50] Quoted in Hugh Cunningham, Leisure in the Industrial Revolution, p. 95.

[51] Hugh Cunningham, Leisure in the Industrial Revolution, p. 96.

[52] Emma Griffin, ‘Manchester in the 19th Century’ , https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/manchester-in-the-19th-century [accessed 23 April 2020].

[53] Carole O’Reilly, ‘From ‘the people’ to “the citizen”’, p. 137.

[54] Alexandra Park Heritage Group, Alexandra Park Manchester, p.10.

[55] Hillary A. Taylor, ‘Urban Public Parks, 1840-1900’, p. 211.

[56] See Manchester Council website: https://www.manchester.gov.uk/info/511/conservation_areas/932/victoria_park_conservation_area/2 [Accessed 23 April 2020].

[57] Hugh Cunningham, Leisure in the Industrial Revolution, p. 96.

[58] Councillor Asquith quoted in ‘Proposed Park for Chorlton-on-Medlock’, The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 03 May 1884, p. 6.

[59] The Mayor of Manchester (John Graves) quoted in ‘Election of Mayors’, The Manchester Weekly Times, 12 November 1870, p 7.

[60] C. Latimer, Parks for the People: Manchester and its Parks 1846-1926, p. 8.

[61] C. Latimer, Parks for the People: Manchester and its Parks 1846-1926, p. 8.

[62] Patricia Vertinsky, “Locating a ‘Sense of Place’: Space, Place and Gender in the Gymnasium”, in Patricia Vertinsky and John Bale (eds.), Sites of Sport: Sport, Place, Experience, (London and New York: Routledge, 2004), pp. 8-24, (p.12).

[63] Hillary A. Taylor, ‘Urban Public Parks, 1840-1900’, p. 216.

[64] C. Latimer, Parks for the People: Manchester and its Parks 1846-1926, pp. 8-9.