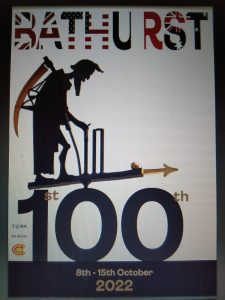

Lord’s celebrated a milestone in October this year, by hosting the centenary of ‘The Bathurst Cup’, which is an international ‘Real Tennis’ competition for amateur players who represent the four ‘Grand Slam’ Tennis nations, of Great Britain, France, USA and Australia. Great Britain were the winners, beating France in a thrilling final 3-2 and also won the first Women’s event, beating The Rest of The World 10-2. Real Tennis has been played at Lord’s since 1839.

Bathurst 100

In 1921, The Tennis and Racquets Association (T&RA) met to give approval for a new tournament, ‘The Bathurst Cup’, which would take place in Paris in 1922 and London the following year. The competition would be open to teams of two to four amateur players representing any country in the world; they would compete using a format of singles and doubles similar to the one used in The Davis Cup (first played in 1900 between Great Britain and the USA ).

Countess of Bathurst

The trophy was given by and named in honour of The Countess of Bathurst who in 1908 had inherited The Morning Post newspaper from her father and was the proprietor until 1924. Exactly why she donated the trophy is still a mystery, but it was suggested by The Field magazine in 1921, that it

‘would do a great deal to spread knowledge of ‘Real Tennis both here and abroad and to carry the revival of interest in the game that has been noticeable in the last few years’.

The first competition was contested between Great Britain and France, with the French coming out on top winning 5-0, but by 1923 the Americans had organised a team and would establish a pattern of alternate wins with Great Britain which was unbroken until 1982, when Australia (who had joined in the 1950s) won the trophy for the first time.

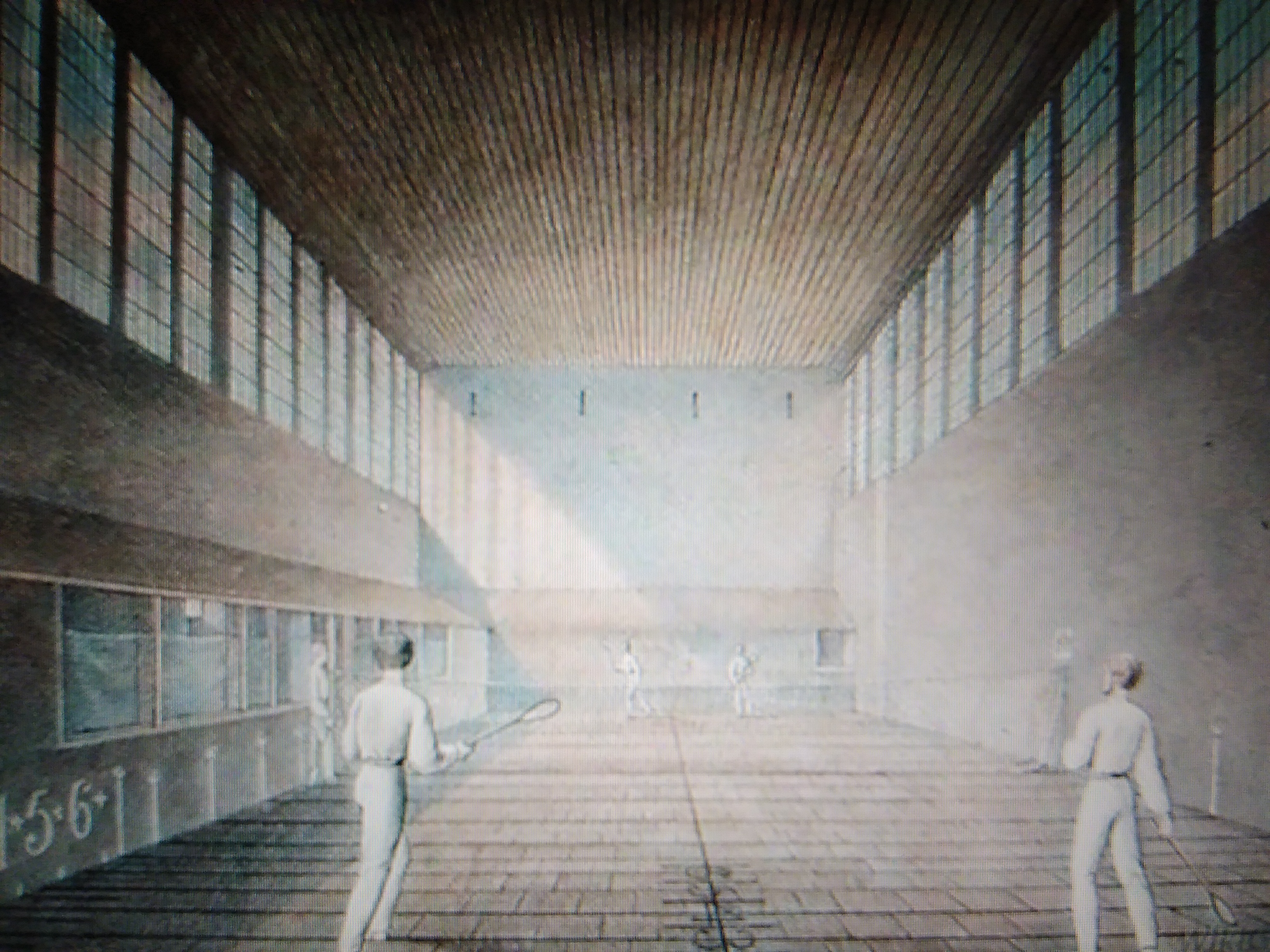

The Real Tennis court at Lord’s

Real Tennis [sometimes called The Sport of Kings), is the original racquet sport from which all modern racquet sports are derived; it is also known as ‘Jeu de Paume in France, where the term, ‘tenez’, which means ‘to take heed and get ready’, is said to have originated. Having evolved from a palm game to a racquet game by the 16th century, the sport moved indoors and established rules and the first codification took place in 1599.

The game thrived among the 17th century nobility in Europe and was often called ‘Court Tennis’, but during the 18th and early 19th centuries, new sports such as Racquets and Squash Racquets (later shortened to Squash) started to become more popular; Lawn Tennis emerged in the latter part of the 19th century, with official rules being drawn up in 1875 which were adopted by The All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club in time for the first Wimbledon Championships in 1877. Real Tennis was contested at the London Olympics in 1908 and was the only games to contain the sport as a ‘medal event’, but for some reason it appeared only as an ‘exhibition event’ at the Paris Games in 1924. It has never featured at any Olympic Games since.

Featuring for Great Britain in the inaugural Bathurst Cup in 1922, he would play a further 17 times, was the 3rd Lord Aberdare of Dyffryn, Clarence Napier Bruce ( 1885-1957).

Clarence Napier Bruce

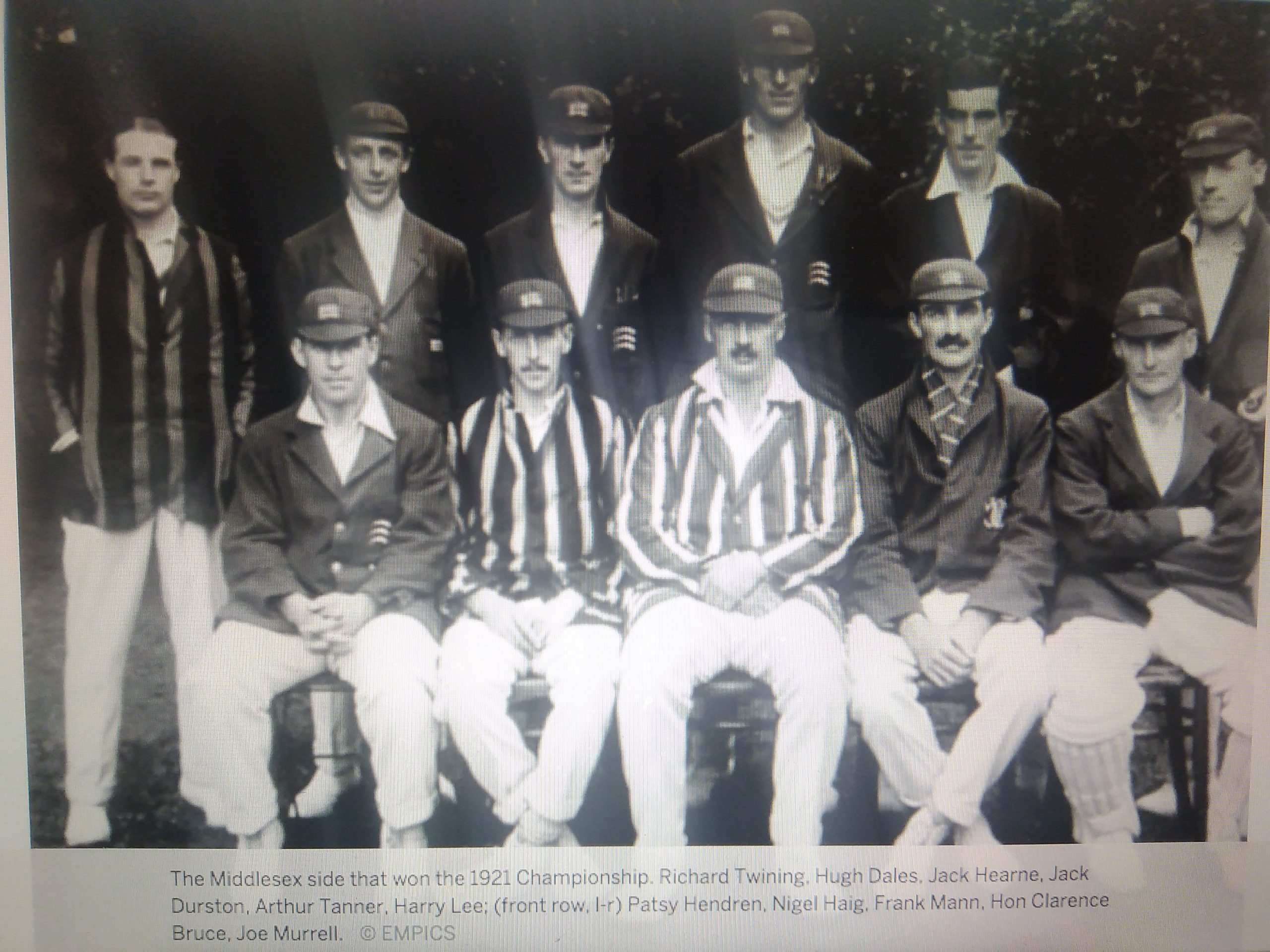

He was probably one of the best known sportsmen of the 1920s and 30s, as not only was he an international Real Tennis player, but also a First Class County Cricketer , Tennis player, Rackets player and Golfer (he played for Oxford against Cambridge between 1905 and 1908 and qualified for The Open championship). Whilst at Cambridge he gained a ‘blue’ for Cricket and went on to represent Middlesex CC between 1908 and 1929, amassing over 4,000 runs during his career. Against Lancashire at Lord’s in 1919, he hit 149 in 2 hours and 25 minutes, in 1921 he scored 144 against Warwickshire and in the same year he scored 127 for The Gentlemen v Players at The Oval.

- Middlesex CC in 1921

- Displaying his trophies in 1932

He was awarded The MCC Gold Prize for Real Tennis on 5 occasions and the Silver Prize 9 times; the MCC Gold and Silver prize competition is the oldest in Real Tennis and has been played regularly ( apart from the war years) and in the same format since 1867. His greatest achievements however, were in racquet sports and he was British Amateur Racquets Champion in 1922 and 1931 and doubles champion on 10 occasions. He was also singles and doubles champion in the US and once a doubles champion in Canada, but his finest achievement was winning the 1932 Open Championship of The British Isles at the age of 46. At Real Tennis, he was British Isles Open Champion in 1932 and 1938( aged 52) and was the US Amateur Champion in 1930. Alongside his incredible longevity in The Bathurst Cup, he also won The Coupe de Paris six times.

After serving as a Captain in the Glamorgan Yeomanry, during WWI, he went on to serve as a Major in WWII, with the Surrey Home Guard. Losing his older brother at Ypres in 1914, he inherited the title and for the rest of his life, dedicated himself to numerous sporting initiatives to promote health and fitness and participation in sport, starting with a fundraising effort to help send athletes to the 1928 Olympics, raising £40,000 (around £ 1 million in today’s money).

After a very successful games in Amsterdam, Napier Bruce argued that the British Government needed to take the health of the nation more seriously and was worried that an undernourished sedentary population was poorly equipped to remain a world power.

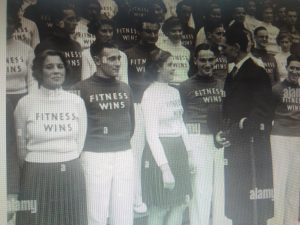

A Major in the Surrey Home guard

All his correspondence is now kept by the Glamorgan Archive in Cardiff and archivist Heather Mountjoy, speaking in 2012, explained how they give a fascinating insight into his motivation. ‘The first thing which strikes you is what a sports fanatic he was’, she says. ‘He also had a deep patriotic concern about the declining health of the nation and where the next generation were going to come from. In many ways his ideas were way before his time and his lobbying of the government led to the establishment of the National Fitness Council in 1937’; he was appointed chairman in the same year.

Speaking to participants at The National Fitness Display in 1937

Napier Bruce also played a very active role in the organisation of The Olympics and served on the International Olympic Committee ( IOC) between 1929 and 1957 and leading up the 1948 London Games , was one of only three IOC members to meet in London in 1945 to discuss the revival of The Olympics after WW II.

‘Lord Aberdare along with Lord Burleigh were most definitely the Seb Coes of the 1948 Games’,

argues Jane Hampton, author of The Austerity Olympics 1948.’ first published in 2008, who continues

‘By 1944’it was clear that the IOC could start to plan the fourteenth Olympiad for 1948 and London remained an option, but Avery Brundage, the vice chair, lobbied for Los Angeles. Napier Bruce, as the London representative, was furious and pointed out that the IOC had already offered them the 1944 Games; London was duly reselected’

He took vicious abuse in the newspapers, the press suggesting it was too close to the end of the war and that they were wasting money on the ‘silly Olympics’!

London 1948

However, he was adamant that sport would help heal Britain and the world and his ideas were to prevail. The BBC was asked to pay £1,000 for transmitting the Games on radio and television and although TV was relatively new, by 1948 radio had fully come into its own. By 1948, it was broadcasting in 43 languages to the world and covering the Olympics would be the largest single operation the BBC had ever undertaken. The 1948 London Games were to be viewed by many as a triumph of the Olympic spirit and fair play.

Opening of the 1948 Games

He also devoted himself to the Order of St John and The British Red Cross Society and became President of the Welsh National School of Medicine in Aberystwyth. He also sat on the research board for The Correlation of Medical Science and Physical Education and was an executive member of The National Playing Fields Association and also took a keen interest in The National Boys Club as Chairman. When he sadly died in a car crash in Yugoslavia in 1957 at the age of 72, his body was flown back to the UK in the hold of the plane, amongst the cellos of The Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra.

His lasting legacy is in the form of the British Society of Sports History annual Lord Aberdare Literary Prize for works of sports history, first awarded in 1994.