FThe author would like to express thanks to Levio Bottazzi and Maura Quiriconi for having shared their memories. Thanks also to Levio Bottazzi for having shared some pictures from his personal archive, and to Lyana Calvesi for doing the same with her mother’s (Gabre Gabric) archive. Some photos are courtesy of Gherardo Bonini.

PLEASE NOTE – Express permission is required to reproduce ANY of the images taken from these personal archives – please contact Playing Pasts or the author for more details.

Some years ago, writing about the birth of Italian women’s football during the Fascist regime, historian Sergio Giuntini noted that the birth of GFC (see https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/football/and-then-we-were-boycotted-new-discoveries-about-the-birth-of-womens-football-in-italy-1933/ ) was a sort of nemesis of it’s policy about women’s sport: the diffusion of the sports activity among Italian girls may have “produced” a physical improvement which was the first goal of the eugenic policy of the government (in response to the population decline after WW1), but also a new kind of sporting mind which was quite different from the traditional one (courage, grit, a spirit of independence). In the opinion of some Fascist authors, such spirit was not a bad thing, at all: the new Italian woman (called donna nuova) might be different from her mother and her grandmother, braver and more helpful to the fighting fate of her husband, ready to help her sons (who would become soldiers for Mussolini). The final part of WW2 was a test bench for these ideas: in 1943, the Fascist Italian Social Republic (RSI) established the Female Auxiliary Service, the first paramilitary women’s corps of Italian History. Since it was a voluntary corps, we could guess that a lot of sportswomen, shaped by long sporting activity carried out in the regime’s youth associations (Opera Nazionale Balilla, Gioventù Italiana del Littorio, Gruppi Universitari Fascisti, Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro), were going to enlist in the ausiliarie: yet it transpired that a lot of them joined the other side, becaming partigiane ‘(female) partizans’ and fighting against the Fascist regime which had, for many years, funded and helped their athletic career. Was it a paradoxical result of the regime’s policy, or just the umpteenth demonstration that women’s sport had been and is, beyond any political consciousness, an emancipatory practice?

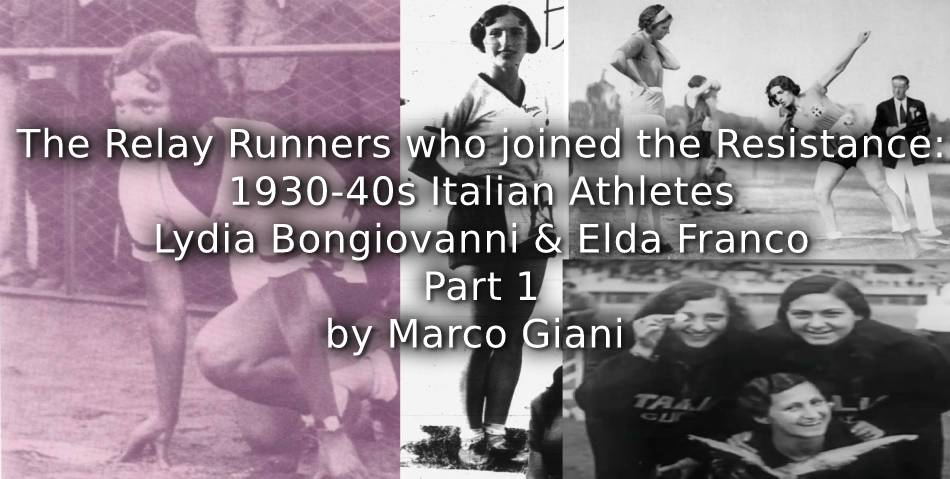

Athletes at the Michelin athletics field, in Turin (no date)

Source: http://bit.ly/3pEYROa

During the last few years, I have searched for any women’s biographies that could cast some light on the decision that some of them made during the war: thanks to the generosity of Levio Bottazzi and Maura Quiriconi, who shared their memories with me during a number of phone interviews in 2019 and 2021, I am finally able to tell Playing Pasts readers about these decisions, in this, the first instalment of the stories of both Lydia Bongiovanni and Elda Franco: in the next months, I will publish a more detailed article for an Italian History journal.

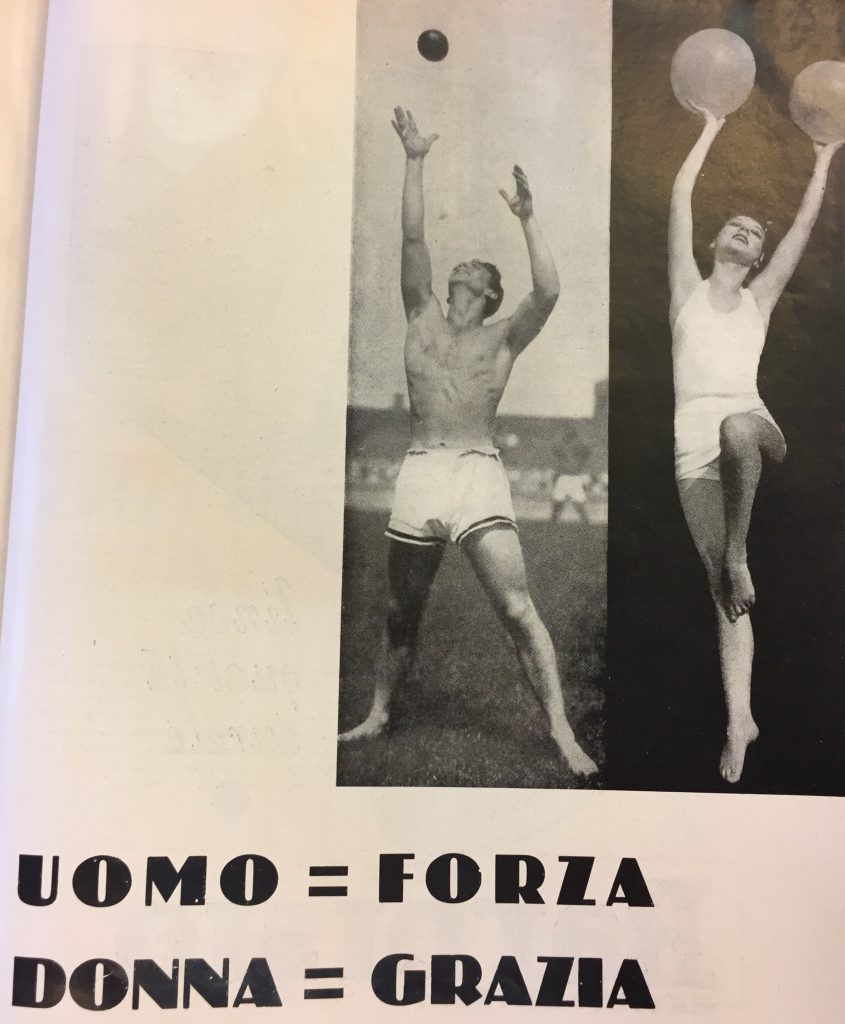

A very significant image, the sum of the Fascist sports gender ideology: ‘Man = Strength | Woman = Grace’

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, December 1934, p. 57.

Lydia Bongiovanni was born in Turin in 1914 to a middle-class family. She had an older sister, Emilia, born in Philadelphia, who later took a degree in Maths (something very unusual, during that time in Italy, for a woman). Lydia began her career in 1929, racing for Società Ginnastica di Torino (SGT). Margherita Scolari, Ellen Capozzi and her friend Giovanna “Nina” Viarengo were her teammates in the 4x100m and 4x75m SGT relay teams, which started to win many gold medals in the Italian competitions of the early 1930s.

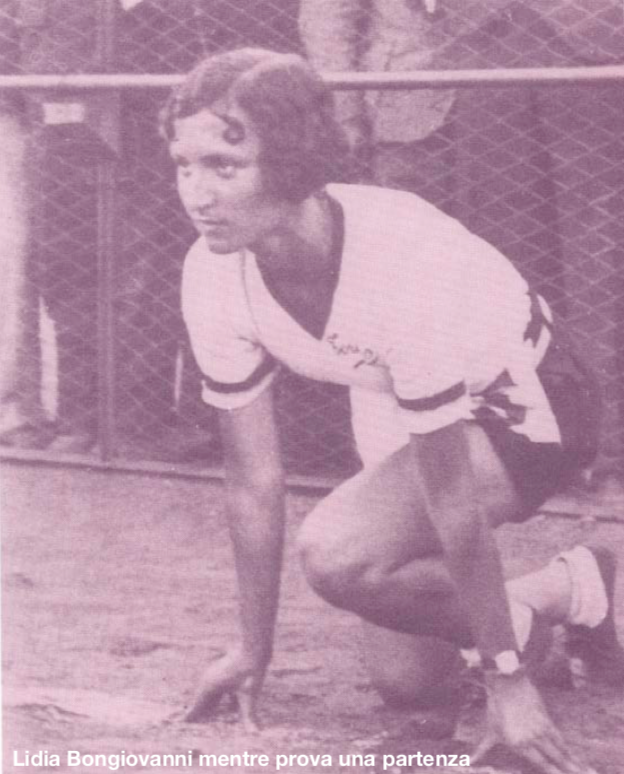

A very young Lydia, with the SGT white shirt

Source: p. 10 of bit.ly/2WHHwdJ

Giovanna “Nina” Viarengo

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, July 1931, p. 4.

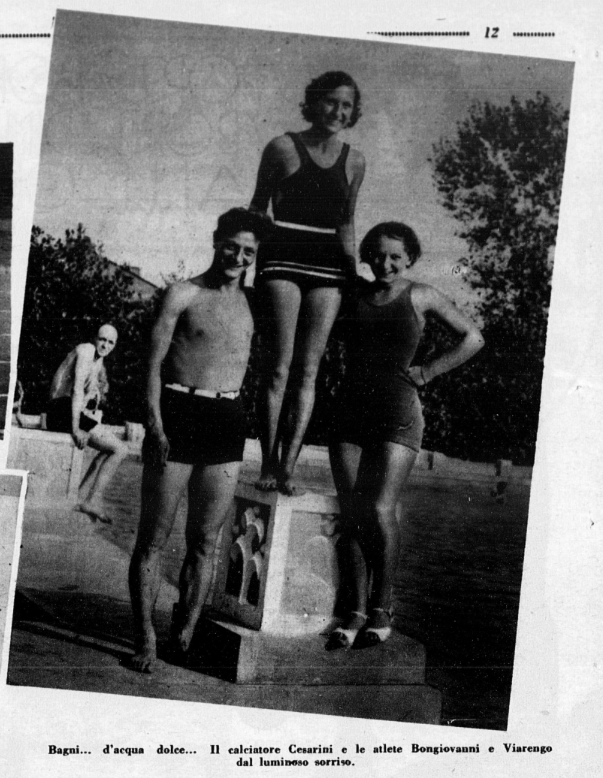

Lydia and Giovanna with the FC Juventus player Renato Cesarini, in a public pool, during the summer of 1932

Cesarini was famous for scoring during the last minutes of football matches, so much so that this part of a match is still called the “zona Cesarini” in the Italian language

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 14/08/1932, p. 12.

The athletes of SGT after the victory at the 1930 edition of Principessa di Piemonte Cup

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, July 1930, p. 54.

As was usual during this period, the runner Lydia tested herself in more than one discipline: in 1931, she equalled the women’s standing high jump world record (1.16m), as well as beginning to compete in 80ms hurdles races.

In the caption, Lydia, ‘a tall and slim girl from Turin’, is praised for being an ‘excellent hurdler and jumper’

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 04/12/1932, p. 11.

In order to understand how poor women’s athletics were in Italy: note that in 1929 National Championship Ellen Capozzi (wearing the white shirt in this picture) won the gold medal in 83m hurdles in 15’’ 4/10 [an unusual distance but it is correct]

In 1936, in Berlin, Ondina Valla won the gold medal in 80m hurdles in 11’’ 7/10

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, January 1930, p. 41.

Lydia winning 80ms hurdles (Ondina Valla gaining silver medal): in 14’’ 1/5, an Italian national record

Source: La Stampa, 21/07/1930, p. 5

Athletes at the 1931 Principessa di Piemonte Cup

The caption praised the ease and the courage of the young girls, who braved the rain to run

Source: Il Littoriale, 19/05/1931, p. 5

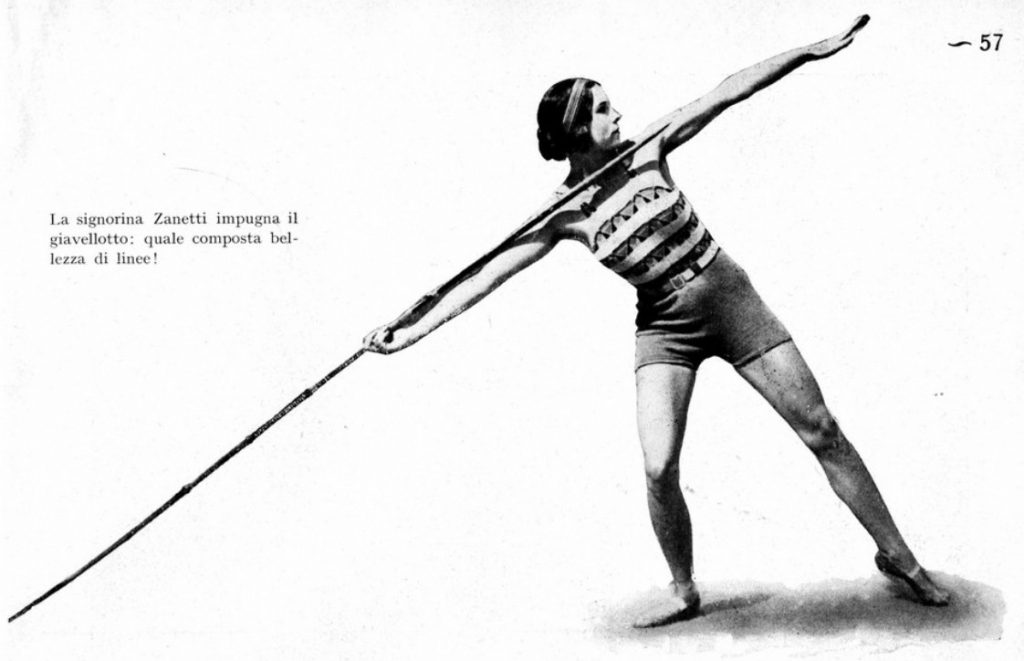

Lydia was soon spotted by Marina Zanetti, a very elegant and still relatively young lady from Turin, born in 1904, who had been and was still a sportswoman herself. Marina was the national women’s coach and the only female FIDAL manager: she would regularly search all over the country for new women who were willing to join the Italian athletics movement, fighting against the social prejudices.

Marina Zanetti literally used her body to promote women’s sports on the Italian press

As here throwing the javelin

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, November 1929, p. 57

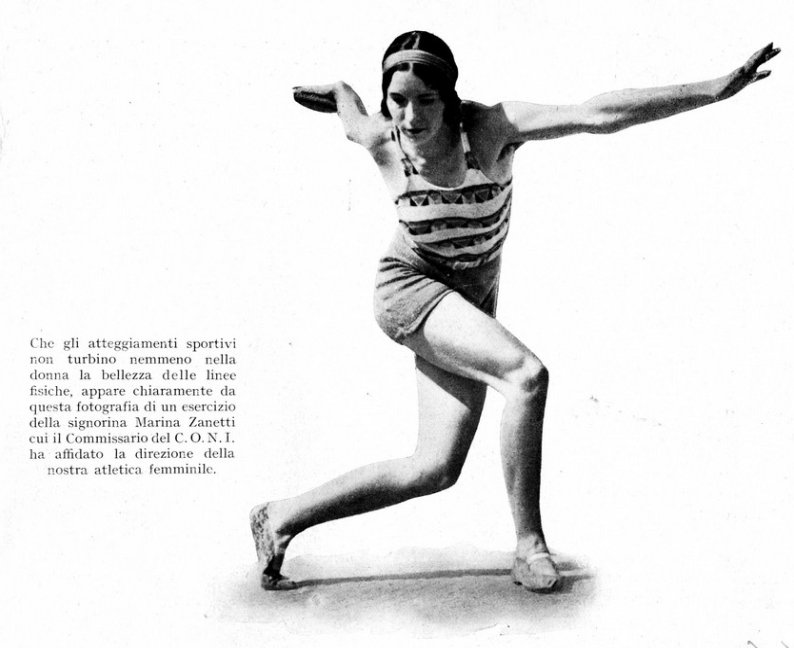

The caption here says that this picture of Marina Zanetti, throwing a discus, shows that women’s sports are compatible with beauty

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, November 1929, p. 55

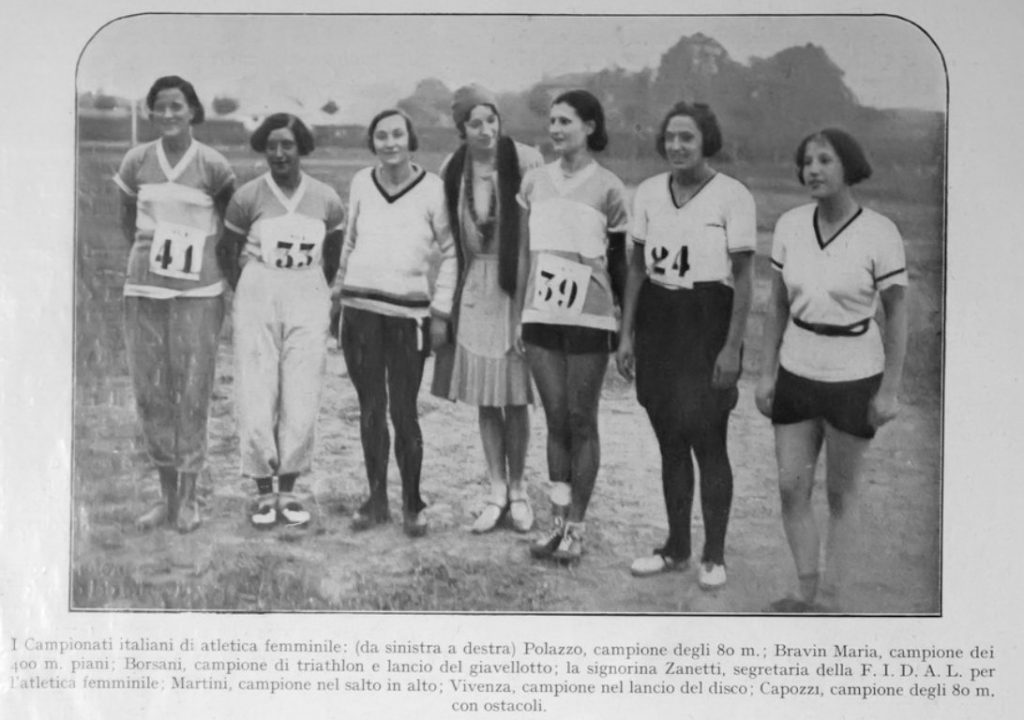

The very elegant FIDAL talent-scout Marina Zanetti (4th) in the middle of the six 1929 National champions

Note that three of them (Pierina Borsani, Vittorina Vivenza and Ellen Capozzi) are wearing the SGT white shirt

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, January 1930, p. 38.

Marina Zanetti supervising a shot put throw by Jolanda Bacchelli

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, November 1933, p. 14.

As Italy women’s athletics team manager, Marina called up Lydia for the first time in June 1930, for the international meeting against Belgium. It was the first of 5 national caps, the others being for the international meetings against Belgium (Florence, June 1930), Poland (Królewska Huta, August 1931), Austria (Piacenza, June 1936), France (Paris, October 1936).

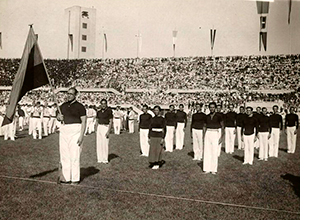

The opening ceremony of Italy vs. Belgium meeting, held in Naples on 19th June 1930

The hosts, wearing dark shirts and short pants, making the Roman salute … then the Italian athletes, wearing a light-blue cap and white skirts

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, July 1930, p. 53

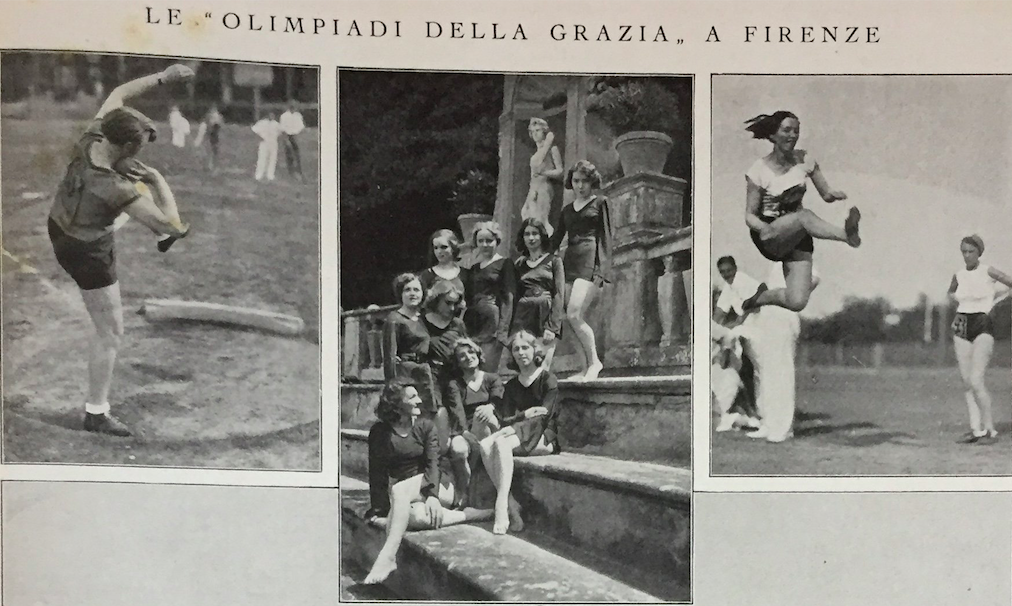

Adding to these five official caps in international meetings, we should add two further events joined by Lydia with the azzurre national shirt. The first was a strange but yet very fashionable meeting, held in Florence in May 1931, called Olimpiade della Grazia ‘(Female) Grace Olympics’: she gained a silver medal in 4x75m relay, with Bravin, Steiner and Viarengo.

A photocollage about the Olimpiade della Grazia

Note how the dancers’ picture at the centre of the page counterbalance the “strong” image of athletes on the right and above all on the left

Source: L’Illustrazione Italiana, 07/06/1931, p. 837.

A running event at the Olimpiade della Grazia

Source: L’Illustrazione Italiana, 07/06/1931, p. 837.

The second event is the one Playing Past’s readers have previously learnt about: the 1933 International University Games, held in Lydia’s hometown (see https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/gender-and-sport/the-italian-jobthe-role-of-italian-sportswomen-in-1933-turin-international-university-games/ ).

It was not a good time for Lydia. Between 1932 and 1933 she had some injuries, while at the same time her two colleagues from Bologna (Ondina Valla and Claudia Testoni) were quickly improving their performances and she wasn’t able to keep up with them. Nevertheless, Lydia was chosen in the trials held in Milan at the end of September: she would compete for Italy in the discus.

An 80ms hurdles event, in Summer of 1933

Ondina Valla and Claudia Testoni lead the group, Lydia (1st from the right) is having some trouble in staying level with the others

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 09/07/1933, p. 11.

Lydia (2nd left) smiling at the Arena Civica during the Milan trials with her teammates: Maria Cosselli (1st), OndinaValla (3rd), Pinta Cipriotto (4th) and Claudia Testoni (5th)

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 03/09/1933, pp. 8-9.

As we all know, Lydia was a member of the winning 4x100m relay team: but what about her gold medal in the discus? Even Luigi Ferrario, the most important Italian athletics journalist, didn’t describe it to his readers, simply saying that the level of the event was very low? So what really happened?

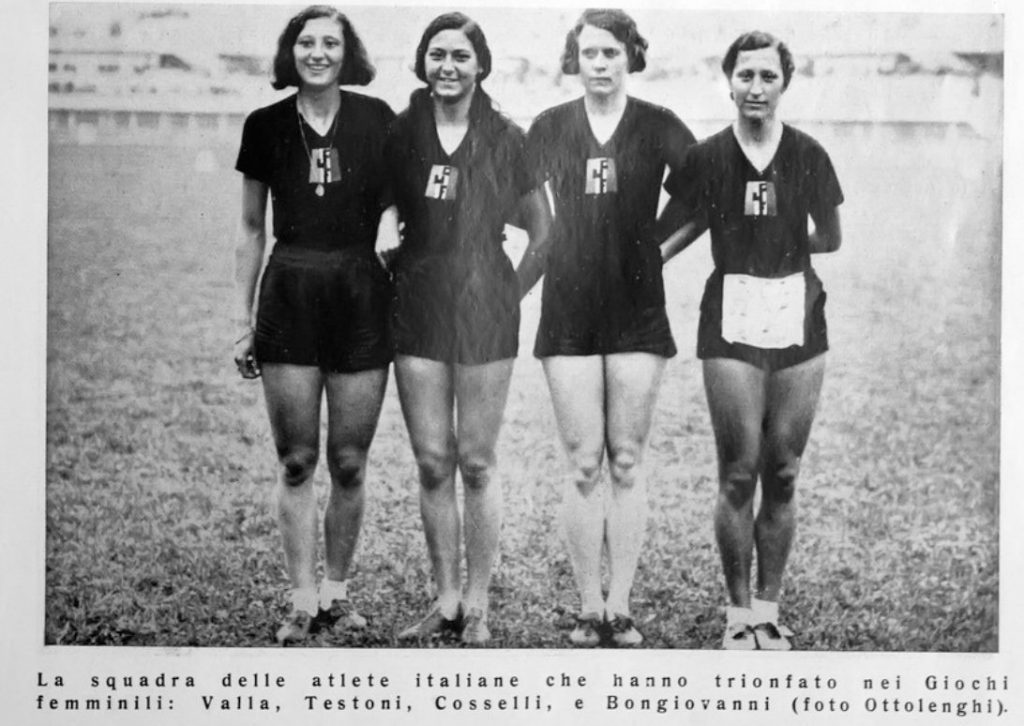

The Italian 4 x 100m relay team: Ondina Valla, Claudia Testoni, Maria Cosselli; Lidia Bongiovanni

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, September 1933, p. 13.

The point was that the quality of the opponents was really low because the best thrower was unable to compete: something that Ferrario couldn’t write about in a newspaper controlled by the regime. To know who this opponent was we have to find sources outside of Italy, and Margot Moles, la gran atleta republicana (2017) by Ignacio Ramos Altamira is the book that sheds a light on this hidden story. The famous athlete Margot Moles, who practiced not only athletics but field hockey, swimming, and skiing, was in Turin with her Spanish university colleagues, regardless of the fact that, due to some disagreement between the Confederación Española de Atletismo ‘National (Spanish) Athletic Federation’ and the Federación Universitaria Española ‘Spanish University Students Federation’, the first forbade the latter to send any athletes under the Spanish (republican) flag.

The flags of France, Czechoslovakia and Germany during the inaugural ceremony

Source: El Mundo Deportivo, 06/09/1933, p. 4.

The Spanish National team

Source: El Mundo Deportivo, 09/09/1933, p. 1.

The Spanish National team at the 1933 IUG inauguration ceremony

Note the Republican flag

Margot Moles is the only female athlete

Source: https://www.rfea.es/web/noticias/desarrollo.asp?codigo=12719#.YC4Yey2h3OQ

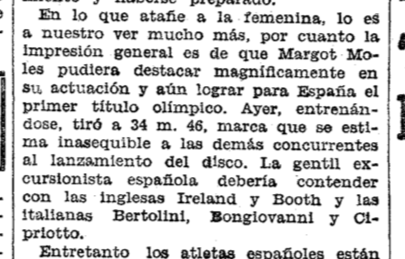

As pointed out by Erminio Fonzo in his recent Il nuovo goliardo (2020), the Italian organizing committee took advantage of this internal disagreement, in order to disqualify for bureaucratic reasons (incomplete registration) those Spanish athletes who were able to gain medals. Fonzo quotes the example of the male tennis player Enrique Maier, but Margot Moles’ example was even more striking as during the training session, she threw the discus 34.46m.

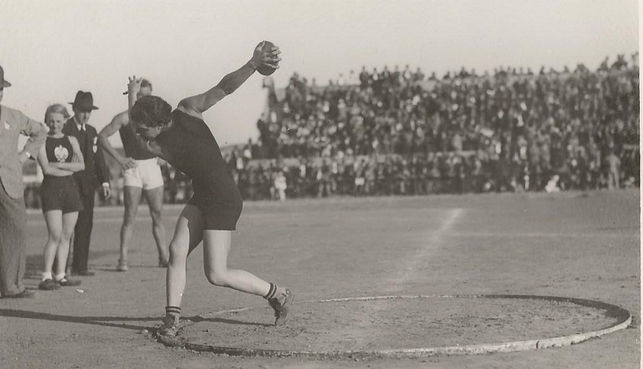

Margot Moles, throwing a discus (not in Turin …)

Source: https://www.rfea.es/web/noticias/desarrollo.asp?codigo=12719#.YC4Yey2h3OQ

A clipping from the Spanish newspapers El Mundo Deportivo about Margot Moles’ 34.46m throw during the training session

Source: El Mundo Deportivo, 09/09/1933, p. 4

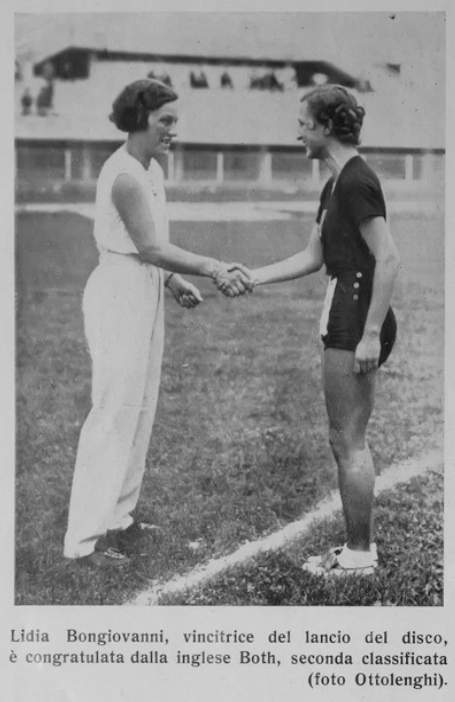

On 8th September 1933 there was a sort of double discus throw event. In the first, official one, held inside of Stadio Mussolini, Lydia Bongiovanni won the gold medal with a very weak throw of 25.62m, a new world university record. The silver and bronze medals was won by Englishwomen Booth and Ireland with weaker throws (24.27m and 22.12m). Please note that during 1932 Olympics US athlete Lilian Copeland won the Olympic medal with a m. 40.58m throw, and that just one month after the Turin Games, Bruna Bertolini won the Italian title with 29.25m. Yet Bruna couldn’t compete at the IUG, although she had been selected in the Milan trials. The Italian press didn’t say anything about her absence: what happened to her? According to a 1982 interview with Ondina Valla, Bruna was thrown out of the Games by the Italian Team manager, because she had been seen to be having too much fun with her American boyfriend. Ondina said that even though she and Claudia Testoni were given a telling off for being out at night, they were both aware that the Italian team needed them!

Englishwomen V. Booth (silver medal) and Lydia (gold medal)

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, Settembre 1933, p. 14.

A collage made by Gabre Gabric with pictures of her colleagues and friends

Ondina Valla (with the black Guf shirt worn in 1933 Turin Games, Bruna Bertolini (wearing a Venchi-Unica tracksuit), Lydia Bongiovanni

Source: Archivio privato Gabre Gabric.

After the official event, the five Italian judges and the Spanish supporter moved outside of the stadium, where the training field for the throws was situated: Margot Moles was going to her unofficial 6 throws. 4 of them were regular, the better 33.66m long. Margot, described as extremely focused and even quite unmoved, was so good that she even tried a 7th throw: 35.02m. It would be not only the new Spanish national record but also the new (real) world university one! Margot was carried on the shoulders of her male teammates: the Italian judges, who couldn’t proclaim her as the winner of the official event, gave her anyway a written minute of her performance, that she will keep in her archive (it has been published in Altamira’s book).

Ondina Valla, Claudia Testoni and Lydia Bongiovanni at the final award ceremony

Ondina is holding a medal and Lydia a big eagle-shaped cup

Source: https://youtu.be/-Cy9L7QsDr4

Article of © Marco Giani

Click HERE to read Part 2