Original research by Marco Giani and with special thanks to Rachel Mc Namara for the linguistic review and translation

1] Following the analysis of journalistic sources, the final step in my historical research on the birth of Italian women’s football is finding their surviving family members, who could provide us with oral accounts of their memories [did these former calciatrici ‘female footballers’ ever share stories about their football years with their relatives?], handwritten sources [such as diaries or letters], photographs, newspaper clippings and any other memorabilia [jerseys, boots … ].

2] Starting from the beginning, Boccalini family offered us a good starting point. In October 2017, while I was writing my first two articles, “Amo moltissimo il gioco del calcio” and “Le nere sottanine”, which were also summarized in the Playing Pasts’ article “Brave (and Clever) Calciatrici under the Fascist Regime”, [click HERE for link] about the Gruppo Femminile Calcistico ‘Female Football Club’, aka GFC , I had the opportunity to have a telephone interview with Paolo Gilardi, son of Rosa “Rosetta” Boccalini Gilardi [1916-1991], the most talented GFC calciatrice, then three-times winner of the national basketball championship with Ambrosiana Milano. On that occasion, Paolo, who was surprised I wasn’t interested in talking about Rosetta’s basketball career, told me that his mother used to tell him that when she was young, she used to play football with her sisters and friends.

3] A few months after my first interview with Paolo, I begin to understand the importance of the role of the Boccalini sisters in the GFC team. In 1927 the family moved from Lodi to Milan and just one year later, their father died, leaving his wife Antonietta all alone to raise their 7 children: Mario [1897], Umberto “Gianni” [1900], Giovanna “Nina” [1901], Teresa “Ginin” [1903], Luisa “Gina” [1906], Marta [1911], Rosa “Rosetta” [1916]. Most of them were fortunate enough to have the opportunity to study and get good jobs, with the exception of Marta, who was not interested in pursuing her scholastic studies and became a seamstress and later an industrial weaver, all of the rest of the daughters became teachers. Giovanna, who had been a socialist activist prior to the Fascist regime, fought as a partisan during World War II, she was one of the co-founders of Gruppi di Difesa della Donna, the first female Italian Resistance groups. After the war, Giovanna, as member of the PCI [Italian Communist Party], was twice elected municipal Councillor for the City of Milan. As previously noted, Rosetta was a relatively well-known figure thanks to her basketball career. However, it was the humble seamstress who was eventually the one who saved the memories of all her sisters.

-

Giovanna’s two Ambrogino medals

These medals [showing on one face St. Ambrose, the patron saint of the Milan] are still assigned yearly by the City Council of Milan to outstanding Milanese men and women.

In 1965, on Liberation Day, all the chiefs of the Milanese Resistance were awarded with a special medal for the 20th anniversary of Liberation from Nazi-Fascist occupation (25 April 1945) in a ceremony that took place at La Scala Theatre

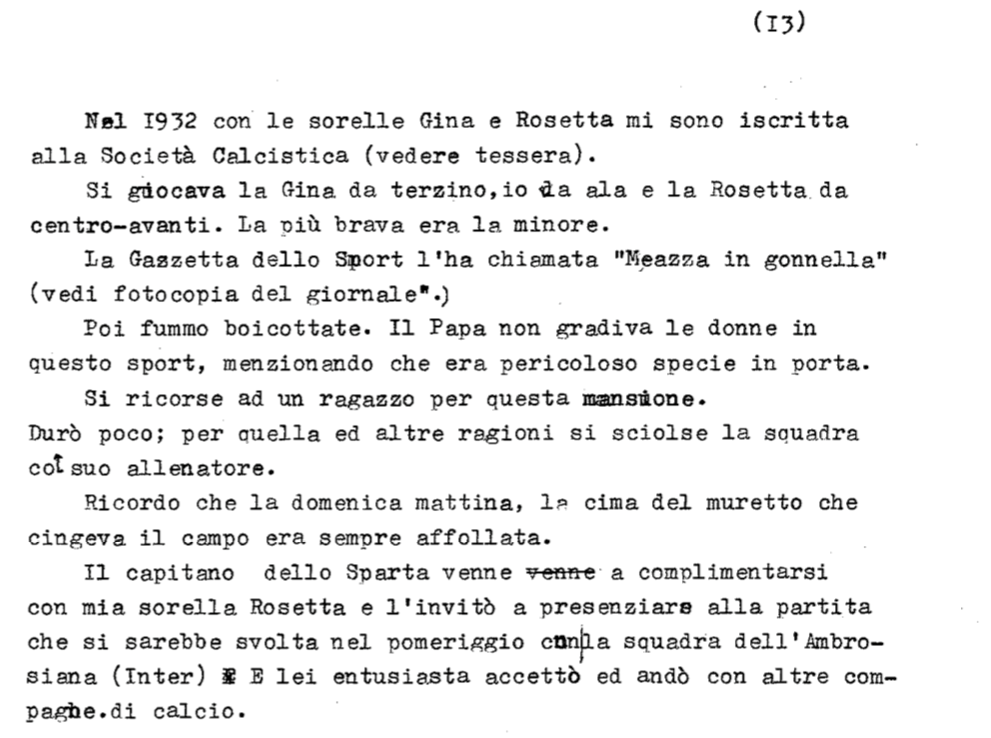

4] Thanks to Paolo Gilardi, I had the chance to read a copy of Marta Boccalini’s Ricordando … ‘Remembering …’ . These 35 typewritten pages of text [that I will be publishing presently in an academic article] contain Marta’s memories, which are for the most part also the collective memories of the Boccalini sisters, their childhood in Lodi, their school years, the move to Milan, their working careers, their marriages and children … and their football team.

On page 13, Marta writes about her 1933 sporting experiences:

In 1932, together with my sisters Gina and Rosetta, I joined the Football Association [see membership card]. Gina played as a full-back, I as winger and Rosetta as a centre-forward. The youngest was the best player. “La Gazzetta dello Sport” called her “Meazza in a skirt” [see the copy of journal clipping]. And then we were boycotted. The Pope didn’t approve of women in football, arguing that it was dangerous, above all for the goalkeeper: as a result, we put a boy in goals. But it didn’t last very long: for this reason, and others, the team (including the trainer) split up. I remember that on Sunday mornings, the top of the wall which ran around the football field was always full of people. AC Sparta Praha’s captain complimented my sister Rosetta, and invited her to attend their match against Ambrosiana Inter that would take place that afternoon. She accepted the offer excitedly, and that night she went to the stadium with some of our teammates.

We didn’t play anything for some time until one day we met Zanetti (a dear football mate), who invited us to play basketball. We didn’t even know what it was, but she insisted so much that she brought us to the ‘Forza e Coraggi’ sports centre. The basketball court was located under a tin roof: it was winter time, and it was bloody cold. I was hopeless: the trainer Sergio (from the Borletti team) told me I was brocco ‘crap, not cut out for it’, while my sister Rosetta was selected for the National team, which caused some uproar among her “forgotten” basketball mates. That team was sponsored by Moratti, the president of Ambrosiana. My sister played a lot of matches and made a lot of journeys. She always travelled first-class, had excellent food and lodgings, but she was never remunerated. Her team won the Italian championship 7 or 8 times. At the beginning, there were very few supporters, but over time the «Forza e Coraggio» gym began to fill up. People liked the game and were interested in it. My sister played in all of the matches, right up until the end of the 1949 season, when she got married. By then she was exhausted. She used to come back from trips (to Rome, Trieste, Naples, Turin …. ) a Monday morning, and then she cycled to the school where she taught in Nosadello, in the provincia of Cremona, 30 kilometres from Milan. She never missed a day of school!

-

On June 1934, ‘La Domenica Sportiva’ magazine published these three photos, depicting the 3 basketball teams of Gruppo Sportivo Femminile Giovinezza, that is the new Fascist sports club used by the regime to encourage the previous calciatrici players to move onto more “female” sports such as athletics & basketball.

In the first image the players are wearing a white shirt, with M [the initial letter of Milan], but in the second & third images, the old football jerseys can be clearly seen …

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 8 June 1934, p. 15

Of course, Marta’s text is full of small historical inaccuracies: GFC was established in Spring 1933, not 1932 (although the idea of the project was probably in its infancy in the summer of 1932); Pope Pius XI wasn’t explicitly against women’s football, rather he was against women’s sport in general (especially athletics); from 1931 to 1942 the President of Ambrosiana Inter was Ferdinando Pozzani and not the famous Angelo Moratti (1955-1968); Rosetta’s team won just 3 Italian championships; evidence of Rosetta’s caps in the Italian national team is still to be found. Nevertheless, this text is of significant historical value, because it is the first ever known testimonial by calciatrici, written in the aftermath of the Fascist regime (this is the key difference between it and the 1933 oral interviews, published in the Italian press). So, at the end of the day, what did Marta still remember about the GFC months? The reputation gained by Rosetta for her football skills; the feeling of injustice for being boycotted; the image of the male audience trying to watch her and her football mates; above all, the meeting between Rosetta and the foreign footballer, and his chivalrous gift.

-

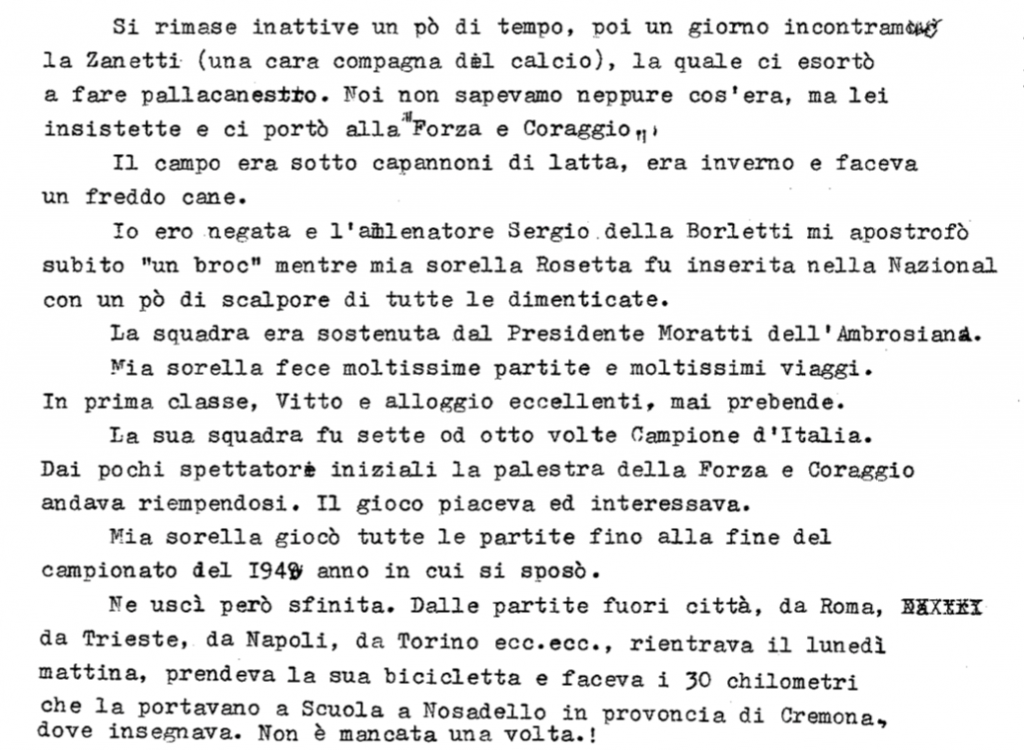

Did Rosetta play official games for the Italian National Team?

In June 1938, she was selected for a 2-days training in Florence, which she joined.

Nevertheless, she isn’t a member of the Italian National Team which won the 1st EuroBasket Women, played in Rome on October 1938

Source: Il Littoriale, 20 June 1938, p. 7

-

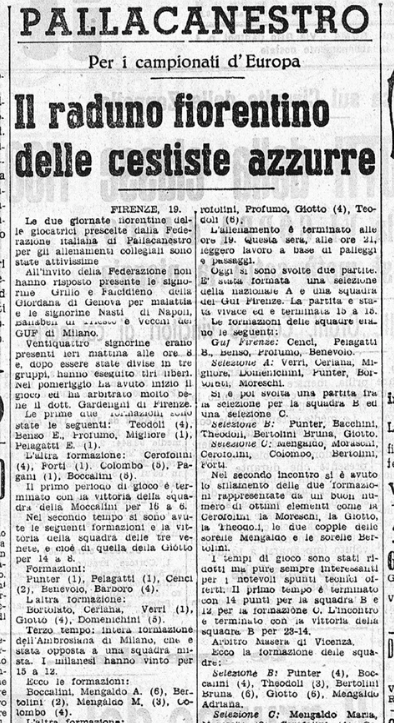

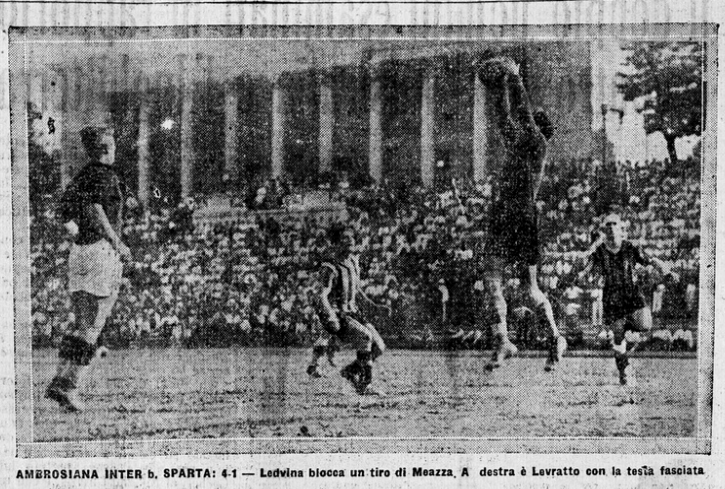

According to Italian press, on 9 July 1933 GFC’s second public match at campo Isotta Fraschini was attended by a audience of 1,000, including managers and players of Ambrosiana Inter and AC Sparta Praha

[on that night, Ambrosiana defeated Sparta 4 – 1, in the semifinals of 1933 Mitropa Cup].

For Ambrosiana Inter, sources report the names of President Ferdinando Pozzani [who congratulated the girls at the end of the match] and Luigi Allemandi.

The Sparta Praha players who reached Milan in the morning of 8 July were: Ledvina, Burger, Ctyroky, Kostalek, Boucek, Madelon, Polcner, Kloz, Braine, Nejedly, Koubei, Sedlacek, Moudtry.

Source: Il Littoriale, 11 July 1933, p. 4

-

During that Ambrosiana – Sparta match, Italian player Levratto got injured and as you can see from the image below, he received an “old school” kind of medication …

Source: Cosmos, Settembre 1933 (n. I), p. 10

-

Ferdinando Pozzani (on the extreme right) had a leading role in Milanese sports life of those years.

Source: Cosmos, September 1933, p. 9

-

Ambrosiana Inter and Sparta players discussing, at the end of the match.

Source: Cosmos, September 1933, p. 25

-

1934 Sparta Praha team.

Source: Il Calcio Illustrato, 13/06/1934, p. 10

For Part 2 of this series see – bit.ly/2JKczw6

Article & Images © Marco Giani

![“And then we were boycotted” <br> New discoveries about the birth of women’s football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 1](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/And-then-we-were-boycotted-New-discoveries-about-the-birth-of-womens-football-in-Italy-1933-Part-1-by-Marco-Giani.jpg)

![“And then we were Boycotted”<br>New Discoveries about the Birth of Women’s Football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 9](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Boycotted-part-9-Marco-440x264.jpg)