The awarding of the 2022 Commonwealth Games to Birmingham came through unusual circumstances, as the city only gained the right to host them after Durban, the original hosts, dropped out. After defeating Liverpool for the British Government’s support, Birmingham were the only city which desired to host the 22nd Commonwealth Games, giving the city their first ever major multi-sport event.

The 2022 Games are not Birmingham’s first attempt to host such an event, as had previously attempted to host the 1992 Olympic Games. This article will analyse Birmingham’s 1992 bid and the reactions to its failure to secure the Games, which were eventually awarded to Barcelona.

Birmingham entered the Olympic bidding race in 1985, just a year before the final vote was to be made, giving it considerably less time than its rivals. Its announcement to bid came after the city convincingly defeated bids from Manchester and London to become Britain’s official bid after a vote of British Olympic Association (BOA) members, winning 25 of out the 32 votes. Despite this support, there was little official support as the British Government offered no financial support and there were reservations from influential figures such as of the two leadings sports journalists in David Miller (The Times) and John Rodda (The Guardian)[i].

Birmingham was one of six cities that bid to host the 1992 Olympics.[ii] Birmingham was joined by Amsterdam, Belgrade, Brisbane, Paris and favourites; Barcelona, from Spain, who had never previously hosted the Games. The consensus was that the 25th Olympiad was to be Spain’s.

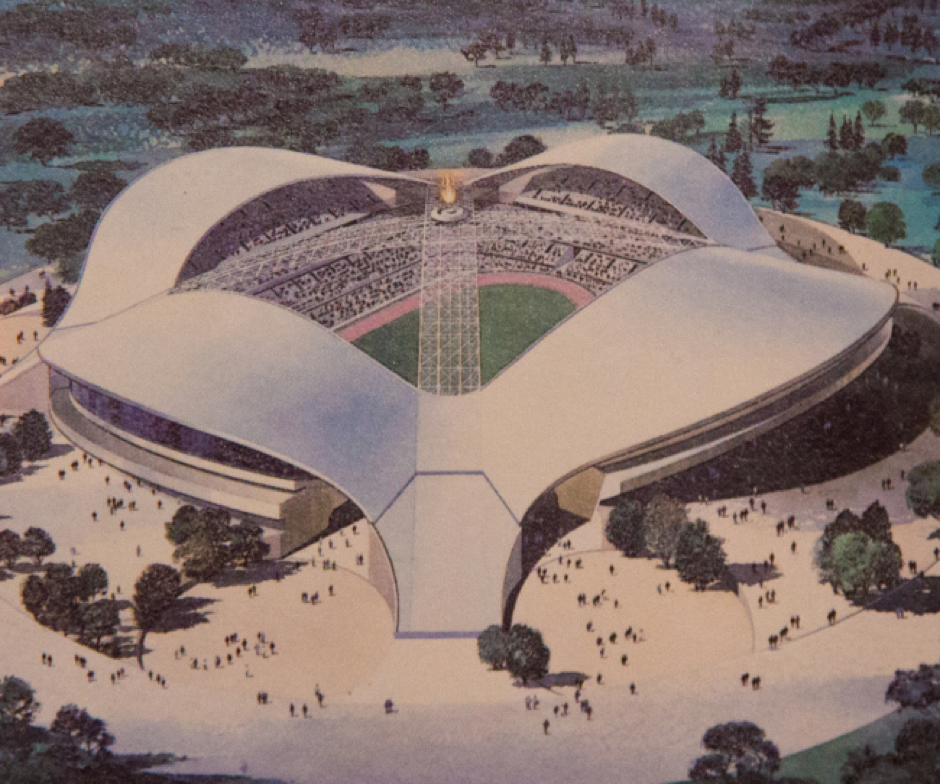

Birmingham’s bid was led by MP Denis Howell and a team that included among others, Sebastian Coe. Birmingham spent £2.3m on its bid, considerable less than Barcelona’s £7m. The belief was that victory would not come through heavy financing, but rather by having a strong technical bid, which featured a ‘revolutionary’[iii] Olympic park and usage of other existing sites across the West Midlands.

- Visual of proposed Olympic Stadium at the NEC for 1992 Bid

Along with the hosting the Olympic Games, Birmingham intended to host the “International Games for Disabled people and the World Wheelchair Games for the Spinal cord injured”[iv] after the Olympics. Since 1960 these Games, (which had yet to gain the title of the ‘Paralympics’), had taken part in the same year as the Olympic Games, twice previously in Rome (1960) and Tokyo (1964) they had taken place at the Olympic venues, a legacy which Birmingham intended to continue. Following the formation of the ‘International Paralympic Committee’ in 1989, the 1992 Games would be known as the ‘Paralympic Games’ and since this all of the Games have taken place after the Olympics in the same venues.

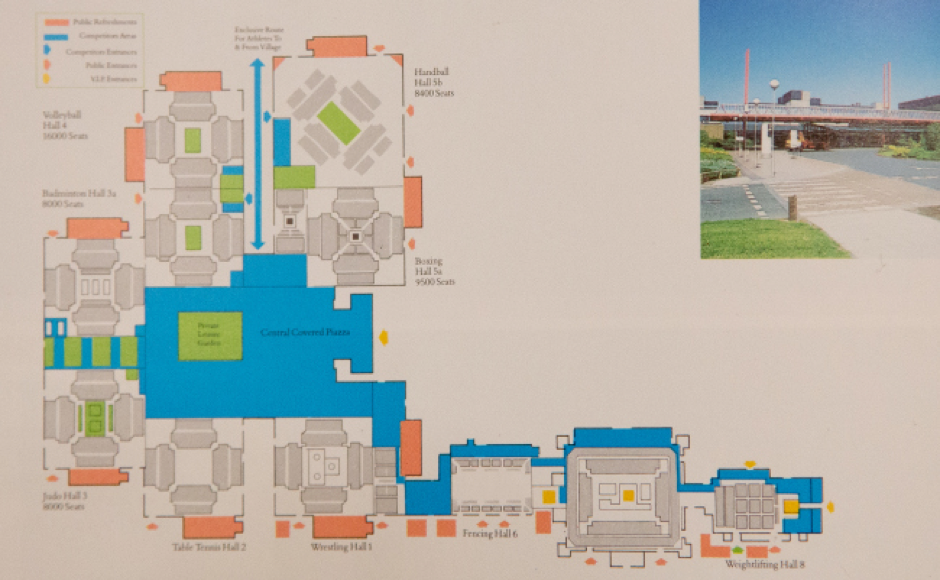

Birmingham’s proposed Olympic stadium was to be constructed so that it wouldn’t become a “white elephant”.[v] Post Olympics it could be used for football, or to add to the National Exhibition Centre (NEC) halls which were located on the same site. Another new facility was a swimming pool, to be built in central Birmingham with 75% temporary seating, space which would be converted into two sports halls. Ominously, the pool would also be converted, leaving a 25m training pool and a “fun pool”, but no 50m swimming pool, a facility that Birmingham remained without until the University of Birmingham opened its 50m pool in 2017.

- Outline plan of the proposed range of venues at the NEC for 1992 Olympic

Along with the athletics, the majority of the events and the athletes’ village would take place on the site next to the existing NEC and chosen because of its proximity to Birmingham’s airport, mainline railway and national motorway links. These factors along with the security assurances (the West Midlands Police envisaged up to 20,000 officers being on call during the Games[vi]) gave Birmingham a strong technical bid. The bid documents predicted that expenditure upon facilities for the Olympics would total £208.9million, of which £104.9m would be spent on the Stadium.[vii] It was estimated that the revenue from the Games could be as high as £689m to as low as £471m, the majority of which would be provided by media rights and the sale of the five million tickets available.

A key principal in Birmingham’s bid was the desire to give the Olympics “back to the athletes”, a value that the Birmingham bid team felt had been taken away from them in recent Games. Christopher Hill believes this dynamic may have been to the detriment of the bid:

…in the end this perfectly unexceptionable slogan seems to have done Birmingham damage because certain members of the IOC could not stomach the suggestion that the Games might have ever been taken away from the athletes, and because Birmingham overdid the use of the slogan in its final presentation to the IOC.[viii]

Another element to Birmingham’s bid that may have had an adverse effect upon its chances its desires to give unbiased television coverage of the Games. Bid team member, Frank Taylor criticised the IOC’s decision to ‘insist’ that the host country organise the television broadcast of the Games, which he believed ensured “how often have we seen TV cameras trained on the host competitors while ignoring the real champions from other countries.”[ix] Taylor stated that Birmingham would give everyone a “fair deal.”[x] This criticism of the IOC through Birmingham’s bid, although unintentional might have counted against the city in the final voting.

Birmingham’s prospects of winning the bid were not aided by Britain’s poor reputation for international sport, which had been recently damaged by the boycott of the 1985 Edinburgh Commonwealth Games by 21 of the 47-member states because of the British Governments attitudes towards apartheid South Africa. British football’s reputation of hooliganism was also seen as harmful. Former footballer and Birmingham bid team member, Bobby Charlton. He felt that “winning the Olympics would be just the tonic to boost Britain’s sagging reputation in international sport.[xi]”

The decision for the 1992 Olympics were made at Lausanne during the 91st IOC Session on 17th October 1986. On the day of voting it was reported that in bookmakers William Hill, Birmingham’s odds had shortened from 25-1 to 2-1, although still behind favourites Barcelona who were priced at 1-3. Despite this optimism, Birmingham was the second city to be eliminated, with only Amsterdam falling prior to her. As expected Barcelona won the right to host the 1992 Olympics.

The lack of official support for the bid was demonstrated by the highest ranking British Governmental official was the barely known Minister of Sport, Richard Tracey, who only arrived in time for last-minute lobbying.[xii] By contrast the Spanish and French Premieres were in attendance throughout. British Prime Minister; Margaret Thatcher’s only input came via a video message that was part of the promotional video, broadcast during the Birmingham Presentation.[xiii]

The result brought was of great disappointment to the midlands press, who believed the city had a realistic chance of winning the right to host the Games. By contrast in the national broadsheets Birmingham’s failure was not major news even within the sports pages. One column that did appear was written by David Miller of ‘The Times’, a longstanding critic of the Birmingham bid. He believed:

Birmingham has done a commendable job in re-establishing Britain’s reputation among the forefront of administrative international sporting competence. It is a pity that British governments, of whatever hue, still grossly underestimate the value, relatively inexpensively acquired, of a high profile sporting event.[xiv]

The ‘Birmingham Mail’s’ headline was “It wasn’t quite all right on the night”[xv] and it featured quotes from embittered local politicians. One comment came from Birmingham City Council Chairman; Dick Knowles, who said “I think we could have got more support from South of Milton Keynes, but we have proved we are one the most vibrant cities in Britain.”[xvi] Another councillor said it was ‘unfortunate’ that Birmingham ‘had to battle without national support”.[xvii]

The ‘Birmingham Post’ praised Denis Howell, claiming the campaign had been a “personal triumph” for the bid’s chairman. It continued “…he and his team have given Birmingham a lot on which to build. The city needs an international standard swimming pool. It needs better sporting facilities for its children. The impetus is there. It must not be lost.” [xviii] The following day’s Birmingham press spoke of bidding for the 1994 Commonwealth Games, 1996 or 2000 Olympics,[xix] for the proposed National Hockey Stadium and Olympic Swimming pool to be built on the NEC site. Despite hopes none of these proposals materialised, with Manchester being Britain’s contender for the 1996 and 2000 Olympics, and the other projects failed to materialise, or were located elsewhere, such as the National Hockey Stadium, built in Milton Keynes.

Birmingham’s bid for the 1992 Olympics was a failure. Birmingham’s bid certainly had a lot of positives, through its planned usage of pre-existing facilities, Paralympic support and its legacy of sporting facilities. The bid also had many shortcomings, particularly its lack of governmental support and also the criticism of the IOC’s television and treatment of Olympic athletes. Barcelona was always a strong favourite to win the bid, which it did comfortably. Birmingham would have to wait 30 more years for the right to host a ‘Mega-event’.

Article © Luke J Harris

References

[i] Christopher R Hill: ‘Olympic Politics: Athens to Atlanta, 1896-1996, p96.

[ii] John R Gold and Margaret M Gold: ‘Olympic cities’, (2nd edition), p275.

[iii] ‘Olympic newsletter’. March 1986. p2.

[iv] Birmingham 1992 Bid Brochure. p28.

[v] Birmingham 1992 Bid Documents: ’10.2.1: The Stadium’.

[vi] 6.3 Security p25.

[vii] Table 8A: Capital costs at Constant prices. p135.

[viii] Hill: ‘Olympic Politics, p97.

[ix] ‘Olympic Newsletter’. May 1986, p4.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] ‘Birmingham Post’. 17th October 1986, p3.

[xii] Hill: ‘Olympic Politics. p98.

[xiii] Birmingham Post. 16th October 1986, p3.

[xiv] ‘The Times’. 26th October 1986, p48.

[xv] Birmingham Mail. 17th October 1986, p3.

[xvi] ‘The Times’. 18th October 1986.

[xvii] ‘Birmingham Post’. 16th October 1986., p3.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] ‘Birmingham Evening Mai’. 20th October 1986, p5.