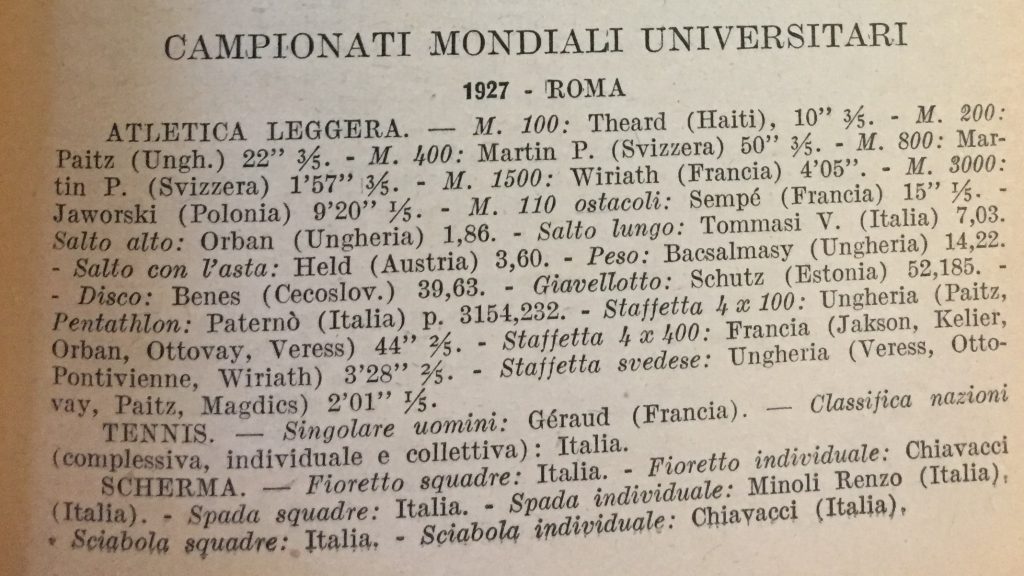

Source: Archivio Storico della Città di Torino [bit.ly/2xlJIZp]

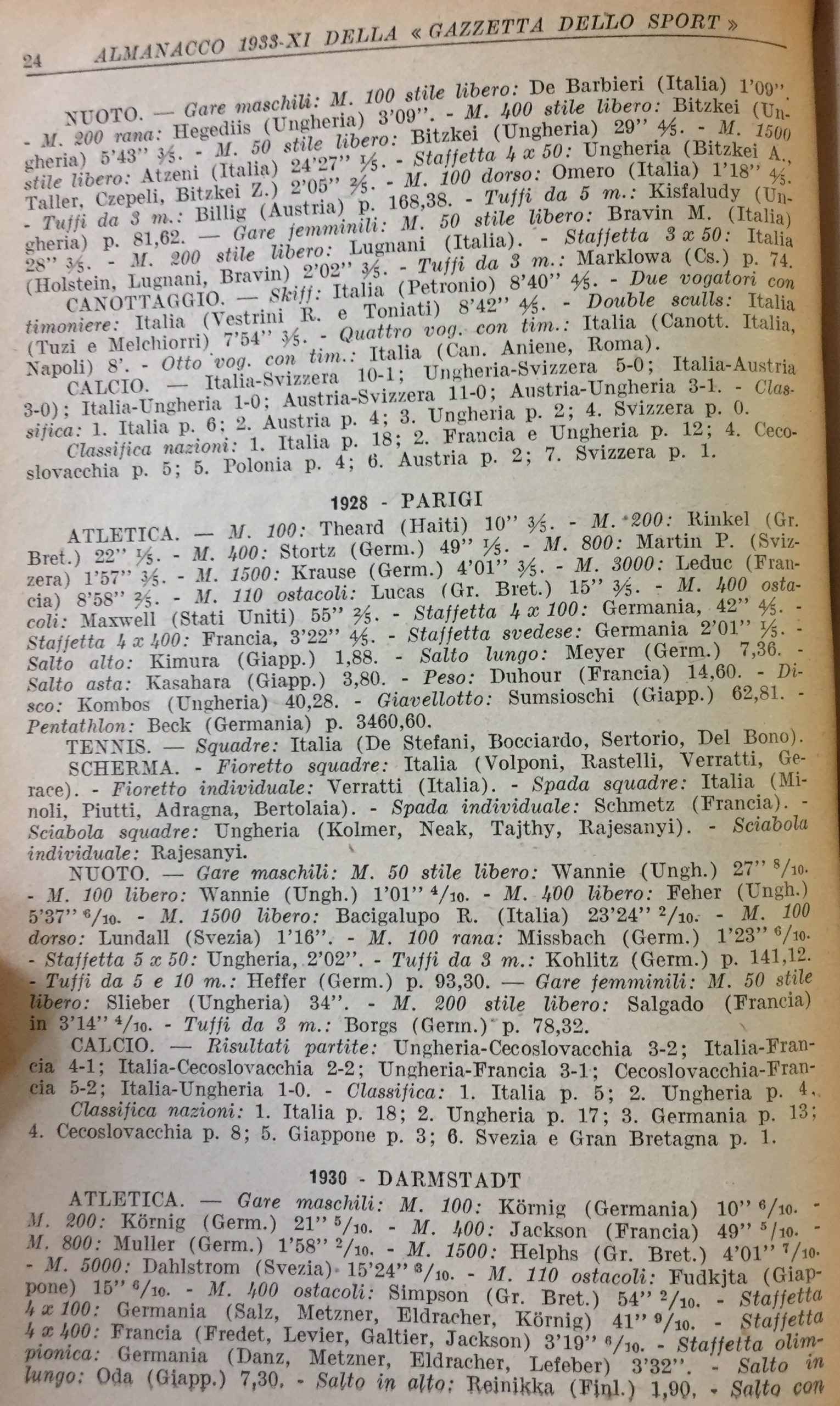

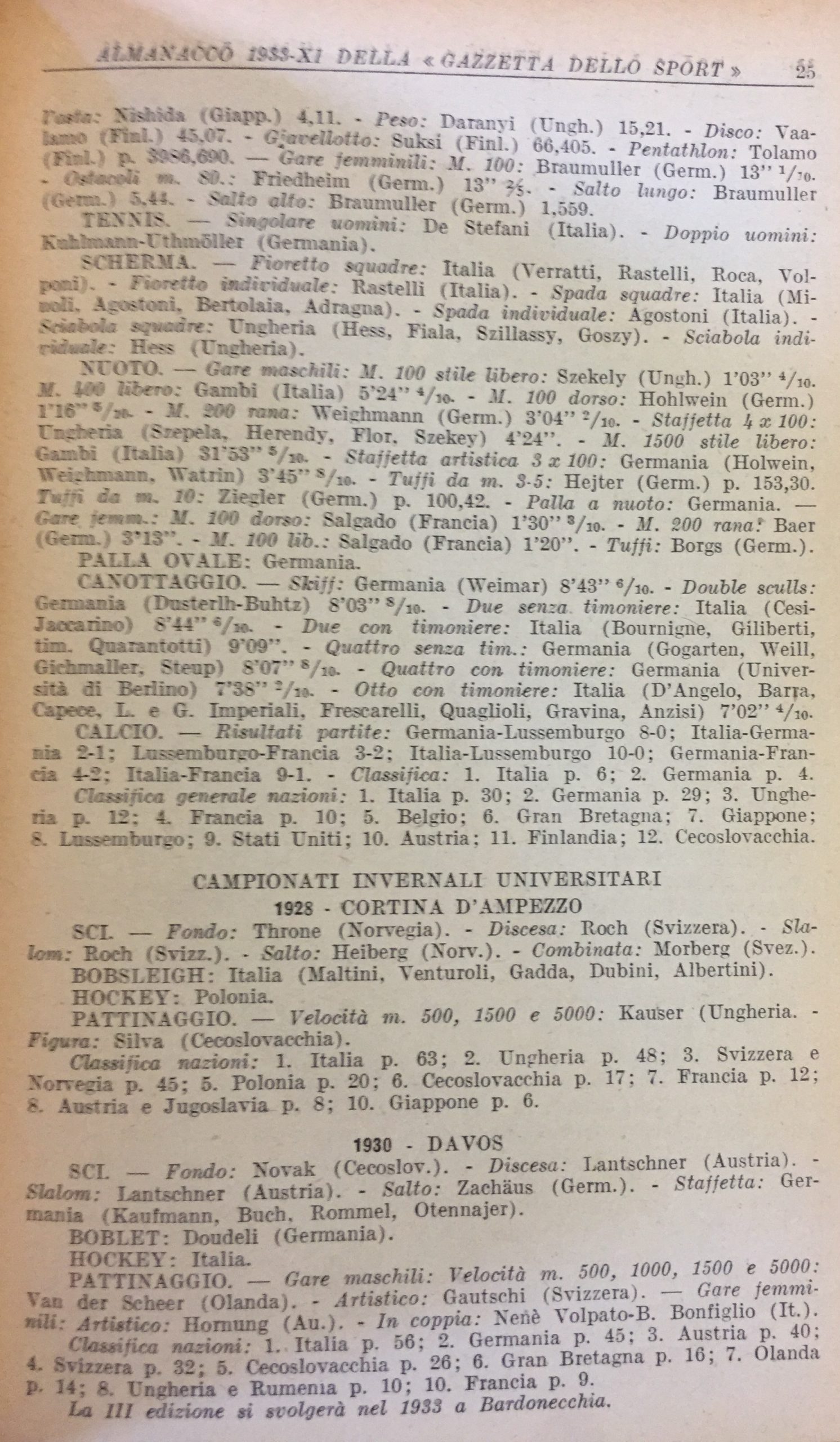

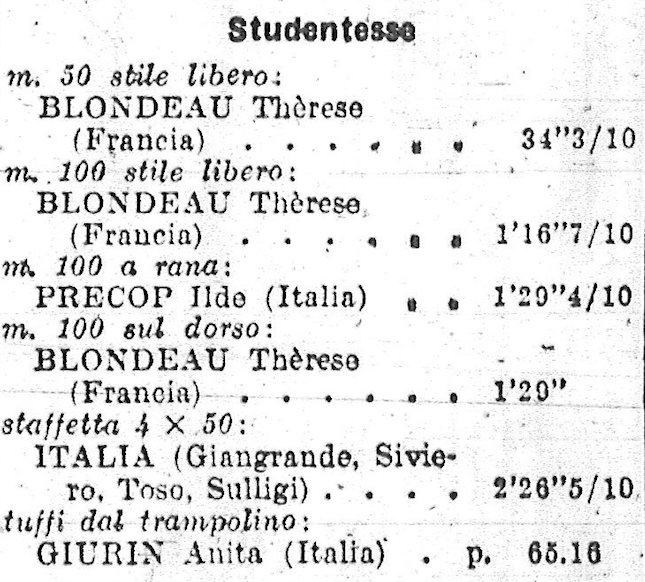

- The results of International University Games, from 1927 to 1930, according to the 1933 Yearly Book by la Gazzetta dello Sport.

-

Source for the three images:

Annuario 1933 della Gazzetta dello Sport, pp. 23-25

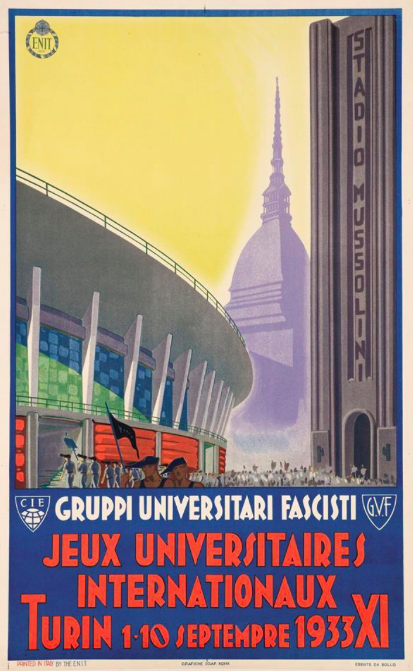

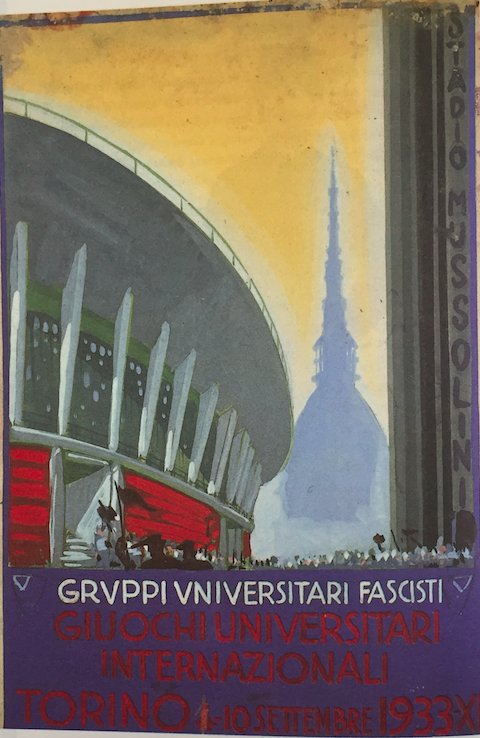

One year before the football World Cup, the 1933 Turin Games, being an international event, would have been a huge occasion for the fascist regime to host, thereby showing the world how things worked well, in the country ruled by Mussolini. The place itself was very significant, since the new Stadio Mussolini (today the Stadio Olimpico Grande Torino), built in Razionalista style and inaugurated just some months before in the occasion of the Littoriali (Italian University Games), was meant to be a symbol of the new, modern Italy.

On this poster the new Stadio Mussolini is at the front, a symbol of the new

At the back, the old symbol of Turin, the Mole Antonelliana

Below, you can see a pair of students wearing the typical long hat of university students

Source: http://bit.ly/2TyutqV ; http://bit.ly/2xlJIZp .

- The most significant element of the stadium was the Torre Maratona (which can be seen also in the Bologna stadium, built during the regime years): after the fall of the regime, of course, the MUSSOLINI fonts were displaced from the tower.

- Source: (1) Illustrazione del Popolo, 21/05/1933, p. 1; (2) Wikipedia

The opening ceremony was a success for the Fascist propaganda: all the national teams paraded not only in front of a large audience but also under the appreciative gaze of Achille Starace, Secretary of the National Fascist Party (PNF). Thanks to a video by British Pathé (not a company ruled by the Fascist regime, at all!), we can still watch several national teams making the Roman salute when walking under the officials box (France and Switzerland), while others didn’t (UK, USA): a powerful hint of the propaganda success, which was able to exploit the presence of foreign athletes … long before what the Nazi regime would do in 1936 Berlin Olympics!

At the end of the video, Achille Starace says: ‘To you, university students from abroad, I express the blunt comradeship of the Blackshirts of all Italy who were happy to learn about your joining our sporting event’. At the end of the speech, Starace hailed to Mussolini, the Duce. Source: https://youtu.be/4iNVN6PdWIQ

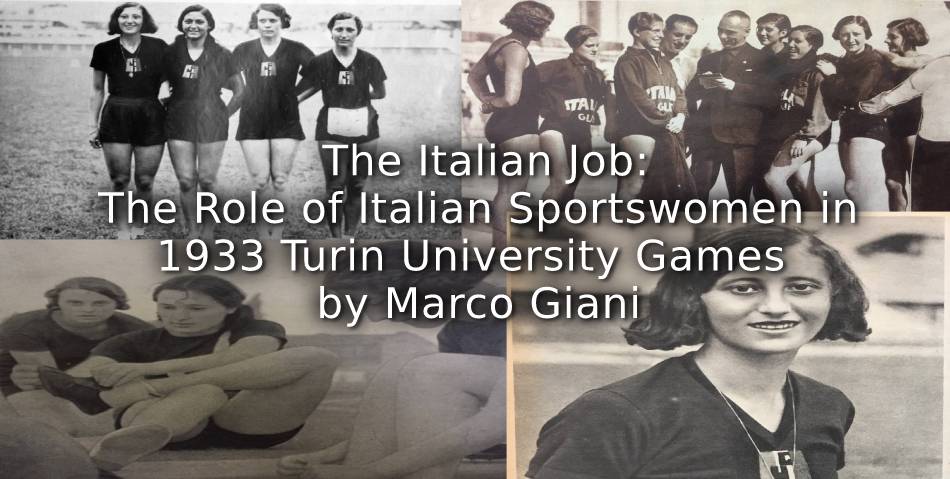

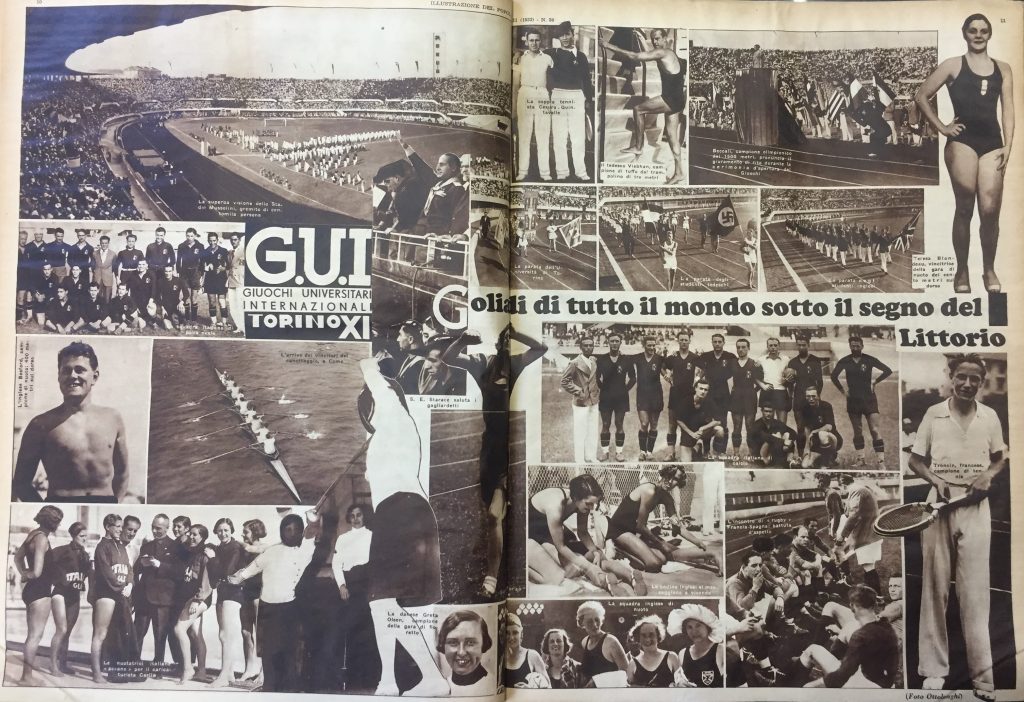

In this photo collage we can see three iconographical elements:

The modernity of the stadium, the presence of the foreign athletes and the Italian victories.

The title reads: ‘University students from all over the world under the sign of the fasces’.

Source: Illustrazione del Popolo, 17/09/1933, pp. 10-11.

The Italian National team during the opening ceremony, in Stadio Mussolini:

The women, wearing a white beret, were at the end of the line.

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, September 1933, p. 2

The best success, of course, would be the victory in the medal tally: Italy was 2nd at the Los Angeles Summer Olympics, just one year before … Turin was the first big international event since the dawning of the new policy of Fascist Italy regarding women’s sport. At the 1932 Olympics, the Italian National Olympic Committee decided not to send any women (neither Ondina Valla nor Claudia Testoni) to America: while in Turin 1933, not only did the Italian university authorities bring women, but also ‘bent the rules’ somewhat by signing up young girls who were not actually university students … Anything goes, for the PNF ruled by Starace: a cynical policy that would also be repeated at the 1934 World Cup, when coach Vittorio Pozzo used a lot of oriundi (foreign people with Italian roots, therefore able to claim Italian citizenship) such as Luis Monti and Enrique Guaita, in order to win the cup.

In his La rivoluzione del corpo (2019) Sergio Giuntini writes that the real reason for Ondina Valla’s exclusion to the 1932 Olympics was not – as she loved to tell in interviews after World War 2 – the opposition of the Pope to the idea that she would be travelling by ship with a male crew, but more the realistic estimation of her abilities by Leandro Arpinati, head of CONI: in 1932 although she was a good athlete, she was not good enough to compete internationally, her participation could prove a big illusion (as happened with the Italian women’s athletics team in Amsterdam 1928). One year later, in Turin, Ondina was not only stronger: but she would compete with university students, an easier kind of competition. Before September, the Italian press started a campaign to depict Ondina as the new hope for Italian sports: she was announced as a key member of the IUG, along with Luigi Beccali (1500m gold medallist from the 1932 LA Olympics) the long-distance runner Umberto Cerati and the men’s football team.

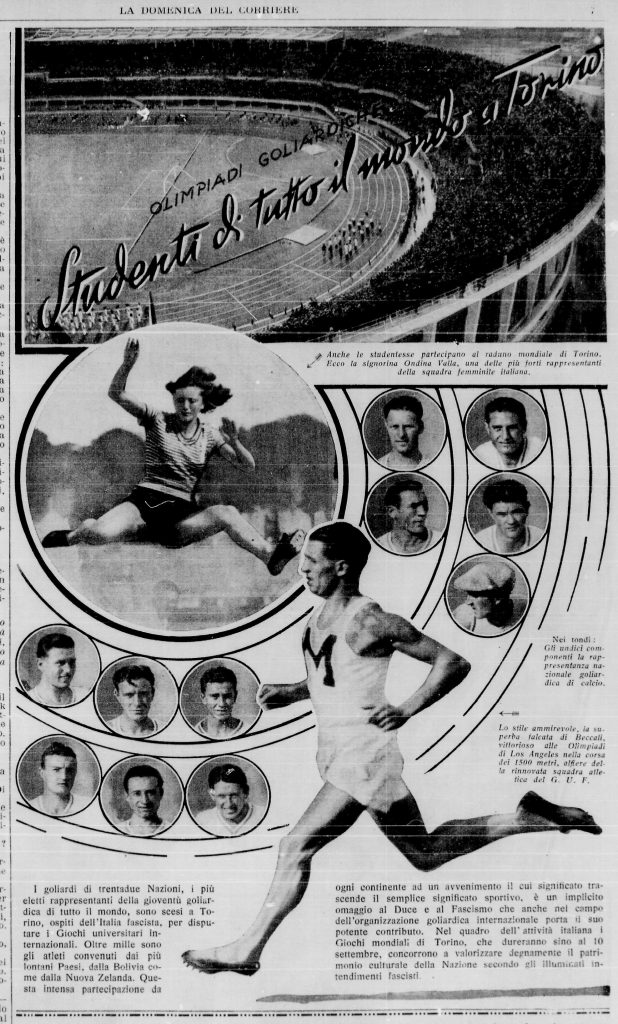

Big expectations for Turin: Ondina Valla, Luigi Beccalini and the men’s football team

Source: La Domenica del Corriere, 10/09/1933, p. 7

The cover of La Domenica Sportiva (La Gazzetta dello Sport’s weekly) issue prior to IUG

Umberto Cerati, Ondina Valla and Luigi Beccali were considered the three main Italian hopes in the event.

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 03/09/1933.

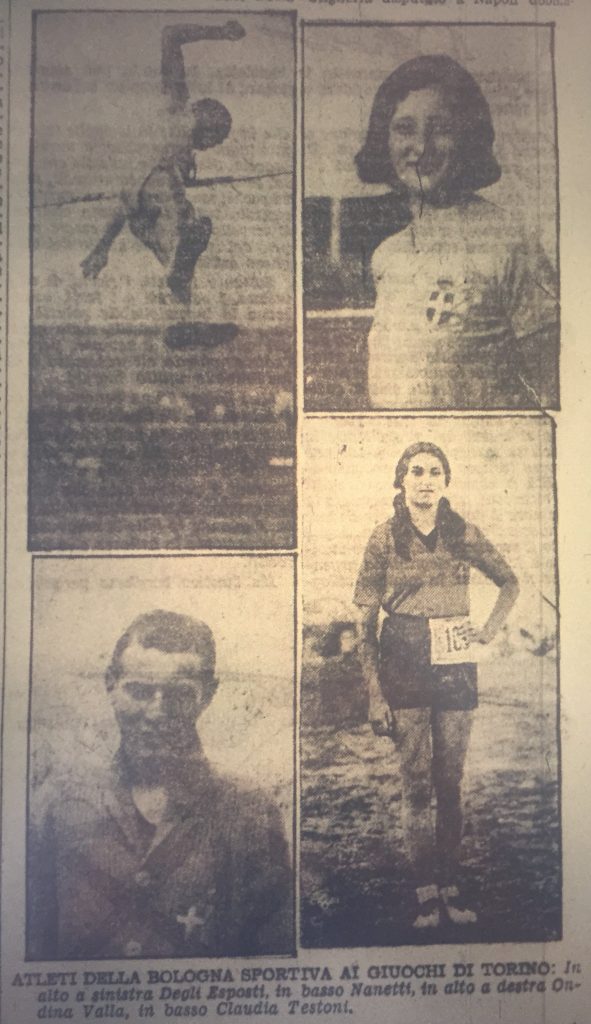

The Bologna-based newspaper Il Resto del Carlino published the photos of four Bolognese athletes who would represent Italy in Turin

Degli Esposti, Nanetti, Valla and Testoni

Source: Il Resto Del Carlino, 31/08/1933, p. 12.

It could be argued that the Italian authorities were relying on the women athletes from the fact that before September they had organized national meetings for each sporting discipline, in order to select those who had a realistic chance of winning medals – internal selection has been undertaken by each local Guf (Gruppo Universitario fascista). On Sunday 27 August 1933, the national athletics trials were held, at the Arena Civica in Milan, and the following athletes were selected: Bruna Bertolini from Turin (discus, javelin), Lydia Bongiovanni from Turin (discus), Pinta Cipriotto from Trieste (discus), Maria Cosselli from Trieste (high jump, javelin, 4 x 100m relay), Claudia Testoni from Bologna (80ms hurdles, high jump, long jump, 4 x 100m relay), Ondina Valla from Bologna (80m hurdles, high jump, 4 x 100m relay), Giovanna Viarengo from Turin (4 x 100m relay).

Valla, Testoni and Bongiovanni would all go on to represent Italy at the Berlin Olympics, three years later.

Original caption says: ‘The selection of the ondine from Genua, in view of Turin IUG. The start of 100m freestyle for women’.

In Italian “ondine” means ‘nixes’: a very interesting reference to mythology, since in the public discourse sportswomen had to keep a sort of feminine gracefulness

Source: La Gazzetta Dello Sport, 08/08/1933, p. 2.

Five athletes selected in Milan during the national trials:

Maria Cosselli (Trieste), Lydia Bongiovanni (Turin), Ondina Valla (Bologna), Pinta Cipriotto (Trieste), Claudia Testoni (Bologna)

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 03/09/1933, pp. 8-9.

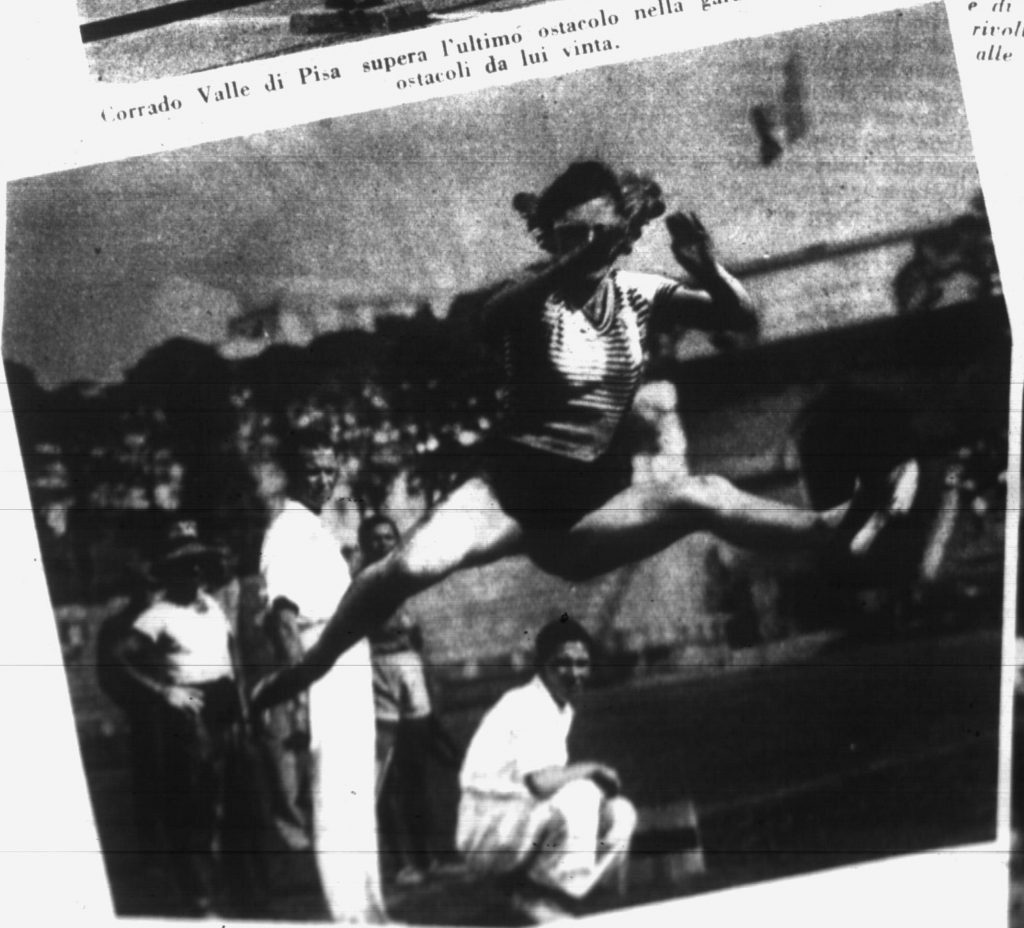

Ondina Valla competing in the long jump at the Milan event

She is wearing a horizontal striped shirt, different from the black shirt she would wear some days later in Turin

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 03/09/1933

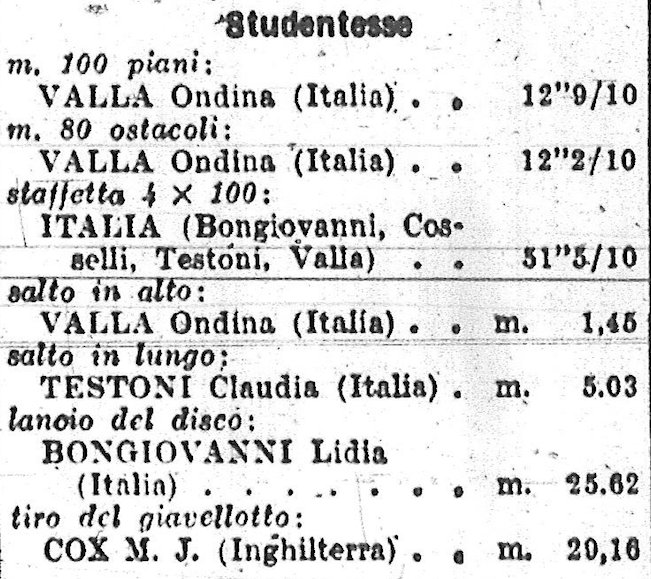

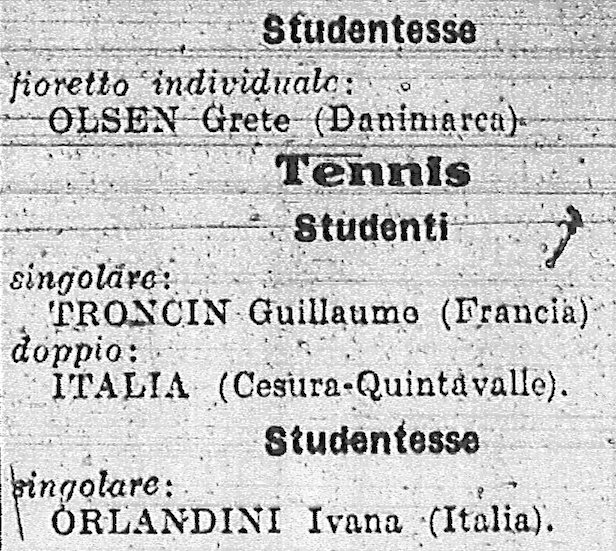

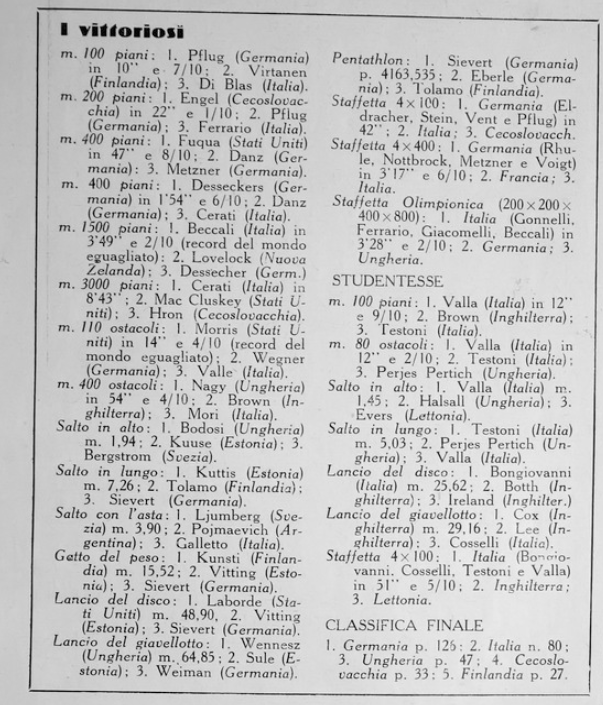

What about the results? In 1933 IUG there were only 5 women’s sports: athletics, swimming, basket, fencing and tennis. Italian students triumphed in 3 of them, gaining a lot of gold medals. Below shows the results of these five disciplines

-

Athletics

Italy won all the gold medals except for one, won by an Englishwoman

-

Swimming

3 of the 6 medals were won by the impressive Thèrese Blondeau of France

Source for all three images: La Gazzetta Dello Sport, 12/09/1933, p. 3

-

Ivana Orlandini won the gold medal in tennis

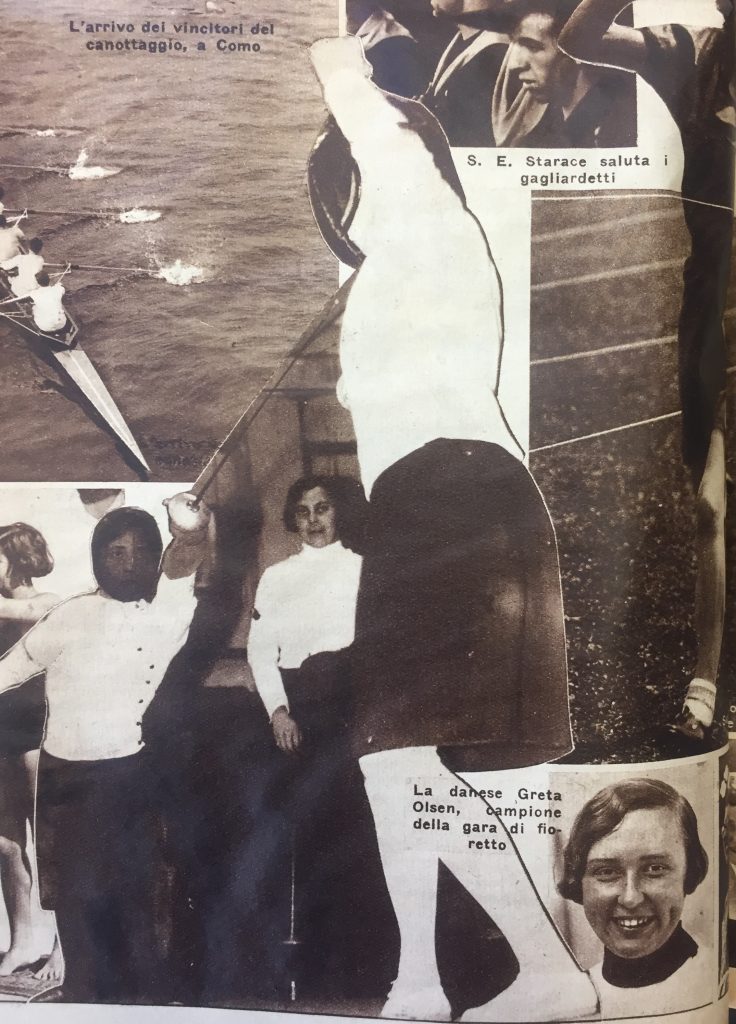

The gold medal in fencing was won by Grete Olsen (Denmark)

Latvia were victorious over Italy for basketball gold meda

Of course there wasn’t a women’s football tournament

Italy won the men’s football’s championship

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, September 1933, p. 13

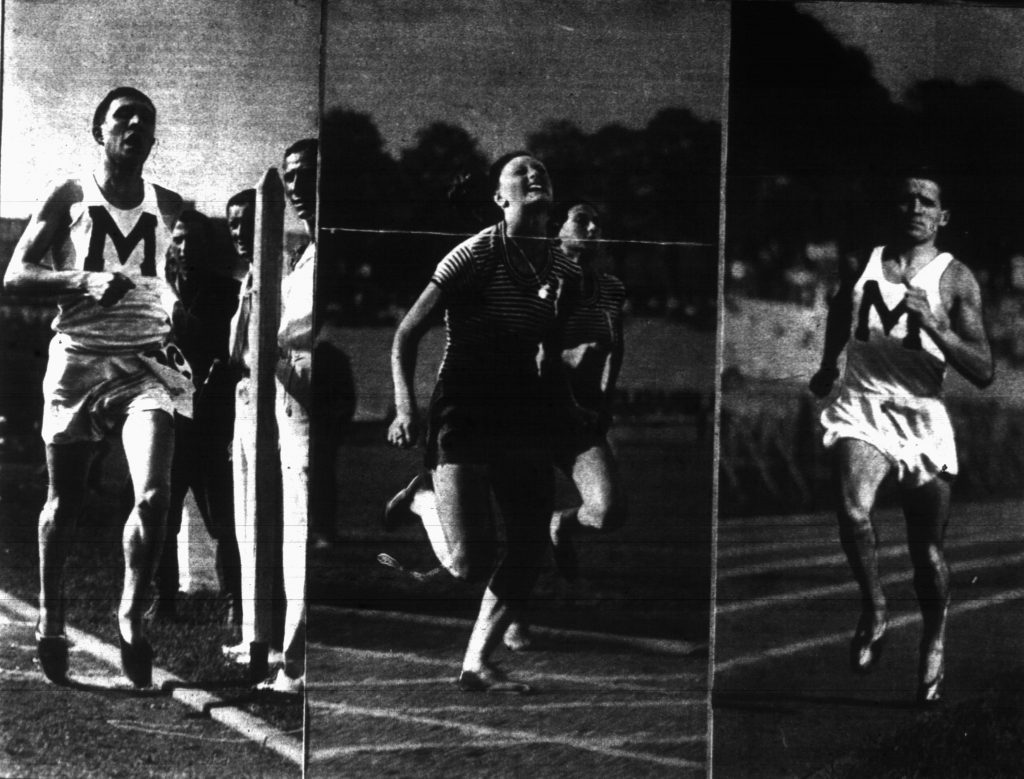

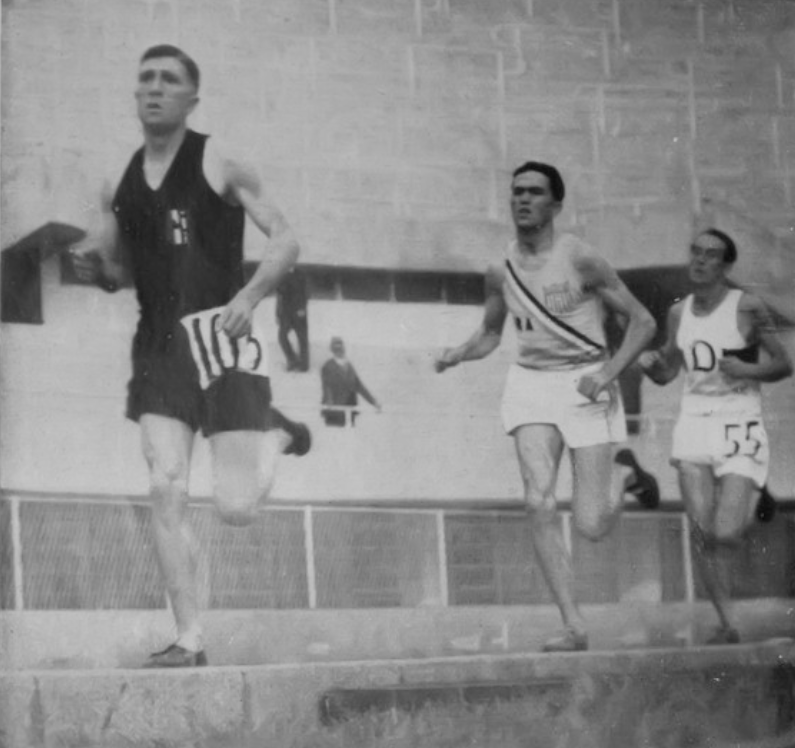

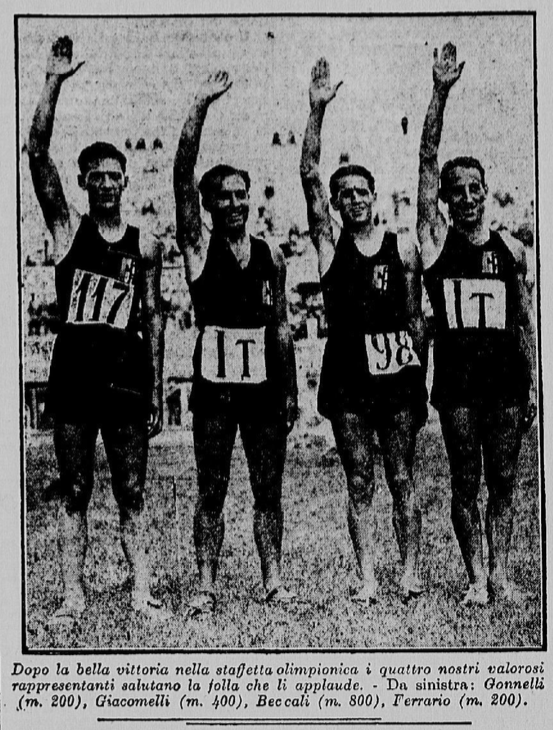

Athletics therefore saw an overwhelming success, where the women doubled the gold medal tally of their male colleagues, who had a good championships, similar to their success the previous year in Los Angeles. The 3 gold medals were won by the Olympic champion Luigi Beccali (1500m), Umberto Cerati (3000m) and the relay team, comprising of Gonelli, Giacomelli, Beccali and Ferrario.

Cerati winning the 3000m; in front of US athlete Mac Cluskey

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, September 1933, p. 8.

The Olympic relay: Ferrario is receiving the baton from Gonelli

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, September 1933, p. 7.

‘After their wonderful Olympic victory, our brave representatives greet the cheering crowd’

Note the use of the adjective Olympic here referred to the Olympic relay, which was run differently from today, the race comprised of 4 legs: 200m + 200m + 400m + 800m

Source: La Gazzetta dello Sport, 9-10/09/1933, p. 2.

Their female colleagues won almost everything they could, bringing home 6 gold medals from a possible 7!

Women’s athletics medal summary, and then women’s athletics tally

Source: Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1933_International_University_Games )

The athletics medal summary

note the difference between the male and the female column …

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, Settembre 1933, p. 5

The journalist from Libro e Moschetto (the weekly magazine of Guf Milano) highly praised the gold medals of Ondina Valla (3 individual medals, plus relay), Claudia Testoni (1 individual medal, plus relay), Lidia Bongiovanni (1 individual medal, plus relay) and Maria Cosselli (relay medal). Italians were claimed to be:

‘better than the very keen Englishwomen and the small opponents from Latvia and Hungary’, but ‘we need some other champions because Valla and Testoni can’t race in every discipline!’.

The start of the 100m race: Ondina Valla (black shirt) second from right

Source: Libro e Moschetto, 16/09/1933, p. 3.

Ondina Valla (second from left) and Claudia Testoni (fourth from left) during the 80m hurdles

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, September 1933, p. 13.

Ondina Valla competing in the high jump

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 17/09/1933, p. 2

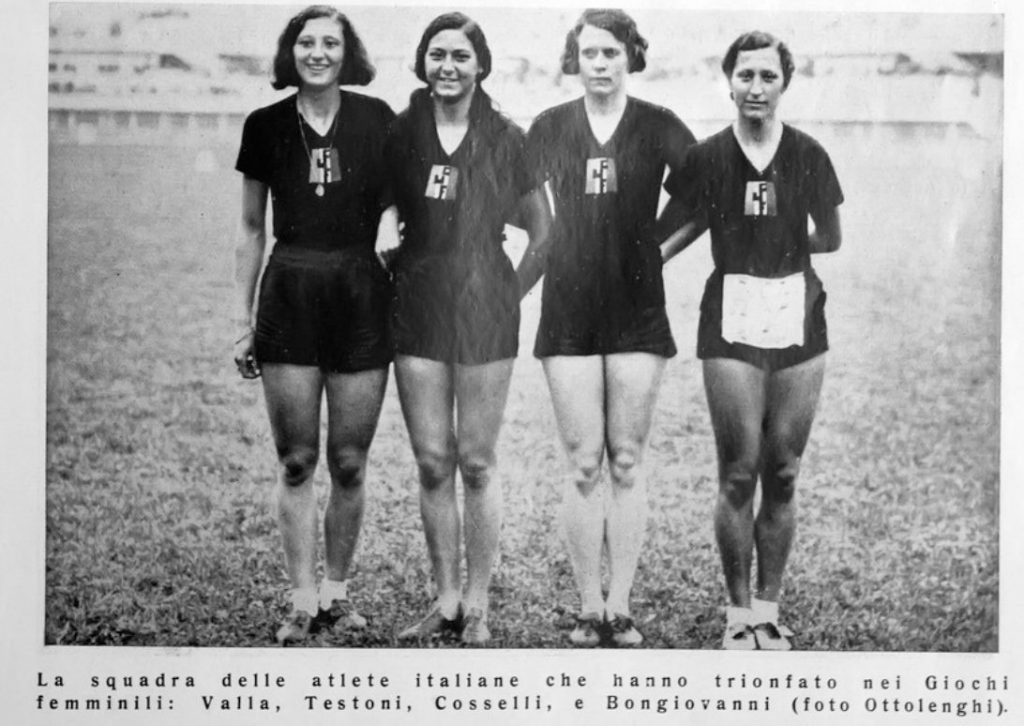

The Italian 4 x 100m relay team

Ondina Valla, Claudia Testoni, Maria Cosselli; Lidia Bongiovanni

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, September 1933, p. 13.

Thanks to a cinegiornale (a short video that was broadcasted in Italian theatres before movies) by the regime’s propaganda company Istituto Luce we can still watch some of Ondina Valla’s feats. In Trionfo di Giovinezza (‘The Triumph of Youth’, but please note that Giovinezza was also the Fascist hymn) there is a clipping about Luigi Beccali’s 1500m victory, and then onto Ondina Valla’s victories in 100m and (standing) high jump. Then, for a few seconds, we can see Ondina Valla, Claudia Testoni and Maria Cosselli at the end of the high jump event: like their male colleagues, they wear the black, rather than the more traditional light-blue, shirt of the Italian university students. The final part of the video is dedicated to the award ceremony: Ondina Valla, wearing a tracksuit, picks up a prize, and then smiles with Claudia Testoni and Lidia Bongiovanni in front of the camera.

The Istituto Luce’s cinegiornale Trionfo di Giovinezza Source: https://youtu.be/-Cy9L7QsDr4

In 1951, after World War II, the women’s magazine Oggi published an article about the great Italian sportswomen

They didn’t mind about publishing this photo from the 1933 IUG, in which Ondina is wearing the black shirt of Guf, which reflects the colour of Blackshirts – in the Guf symbol we can still see the presence of fasces

Source: Oggi_19511206_14.

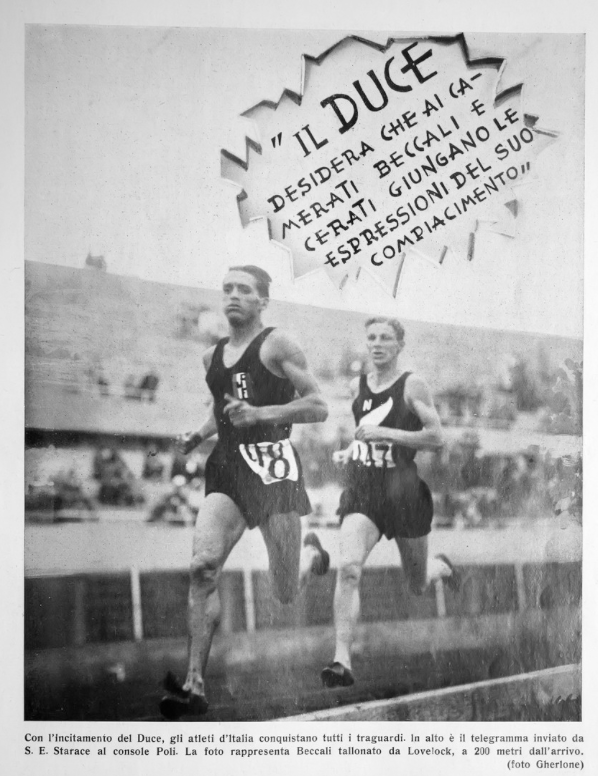

Yet the cinegiornale was quite an exception. A lot of newspapers praised the women’s victories but they devalued them in comparison with Beccali and Cerati’s success: this was the policy of Achille Starace himself, who sent a telegram to the two male athletes, writing that Mussolini wished to compliment them on their gold medals … No telegram was sent to the 6 female medal winners, and furthermore they were not invited to the reception with the Duce in Rome after the IUG, as Erminio Fonzo underlined in his Il nuovo goliardo. Italy was not ready for the novelty of these winning sportswomen who also were created by the regime itself …

At the top of this Luigi Beccali’s photo is a quote from Starace’s telegram

The original caption says:

Thanks to the support of the Duce, the Italian athletes conquer all their goals

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, September 1933, p. 7.

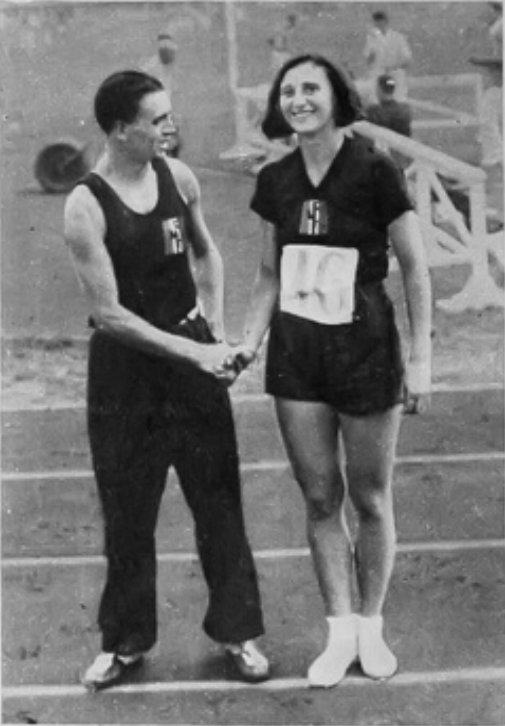

Luigi Beccali and Ondina Valla, male and the female champions, shaking hands.

This kind of ‘promiscuous’ photograph was quite rare, probably because it was a little scandalous even for the most open-minded magazine readers

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 17/09/1933, p. 6

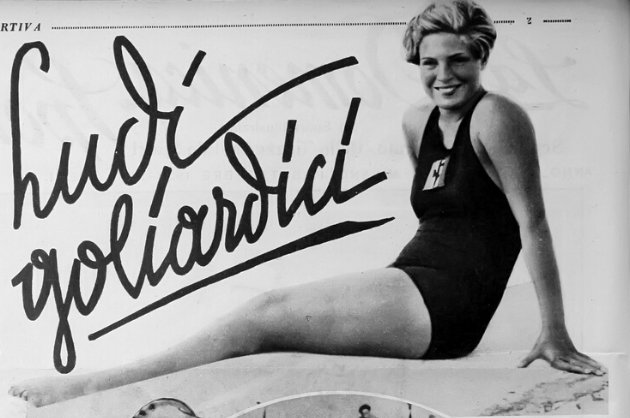

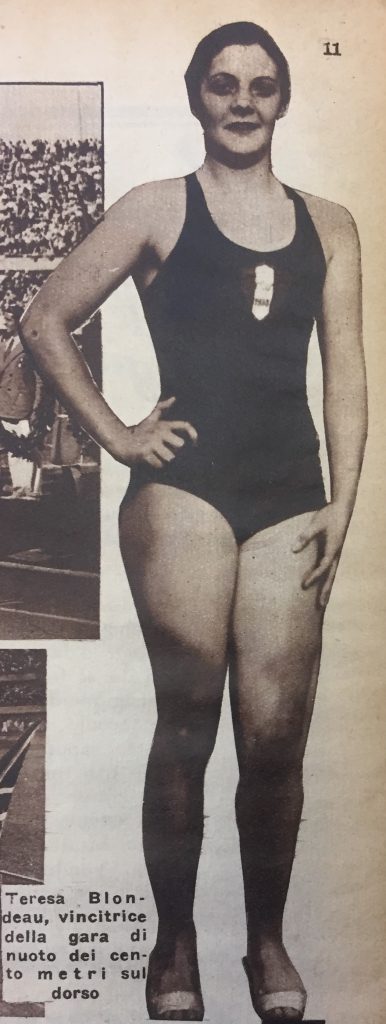

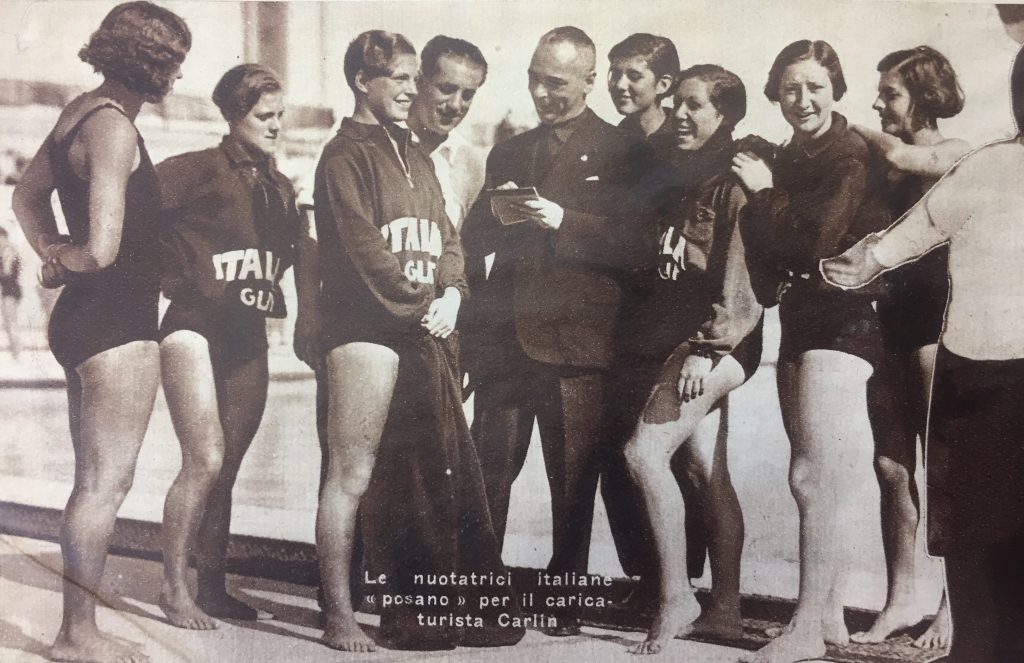

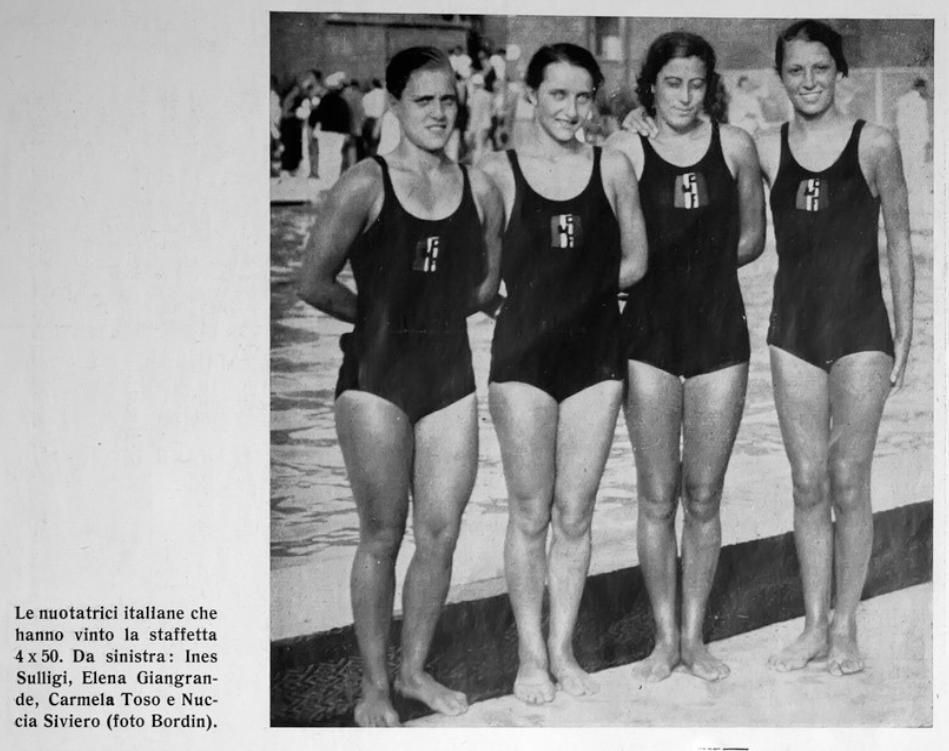

Swimming was the second discipline in which Italian girls were able to gain many victories. Except for the three gold medals won by the Frenchwomen Thèrese Blondeau (50m freestyle, 100m freestyle and 100m backstroke), they won the remaining three: 100m breaststroke (Hilde Prekop), 4 x 50m relay (Giangrande, Siviero, Toso and Sulligi) and diving (Anita Giurin).

Therese Blondeau (France)

Source: Illustrazione del Popolo, 17/09/1933, p. 11.

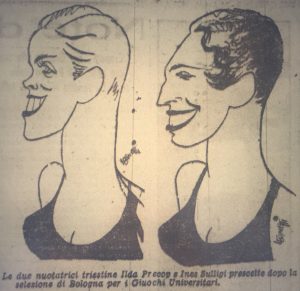

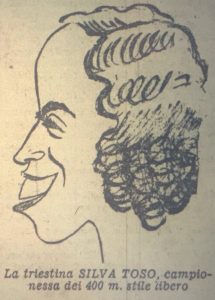

Before Turin, the Italian swimmers (who were mostly from Trieste), had taken part in training days in Bologna at the Stadio del Littorio (the sporting centre built by Leandro Arpinati) in which there were a number of swimming pools. They had to train to swim the shorter distances because some of them, such as the 400m freestyle champion Silvia Toso, were more accustomed to longer distances. Due to their presence in Bologna, local newspaper Il Resto del Carlino published, in late August, a series of cartoon depicting them. Please remember here that cartoons were popular in the 1930s’ Italian sports magazines: illustrators such as Carlin (Carlo Bergoglio) draw a lot of caricatures of male footballers and cyclists. For this reason, depicting the Italian women’s swimmers was quite revolutionary: they were now accepted as part of the national sporting community.

Risella Brighenti (Bologna), Silvia Giedini (Trieste), Nuccia Siviero (Sanremo)

Source: Il Resto del Carlino, 24/08/1933, p. 11.

Silvia Toso, Hilde Prekop and Ines Sulligi (Trieste). All selected after the national trials in Bologna Please note that the name of the second athlete was written as Ilda Precop, because otherwise it sounded too German … Source: Il Resto del Carlino, 24/08/1933, p. 11, and 31/08/1933, p. 12.

The Italian swimmers and Carlin during the IUG.

Source: Illustrazione del Popolo, 17/09/1933, p.10

Although they could do nothing about the sporting excellence of their French opponent, the Italian girls did the best they could: Hilde Prekop broke the 100m breaststroke national record twice!

The winners of 4 x 50m relay (Ines Sulligi, Carmela Toso, Nuccia Siviero and Elena Giangrande) … in black swimsuits, of course!

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 17/09/1933, p. 2.

Another photo of the winning quartet: Ines Sulligi, Elena Giangrande, Carmela Toso and Nuccia Siviero

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, September 1933, p. 19

Male and female Italian swimmers in Turin

Source: Il Littoriale, 07/09/1933.

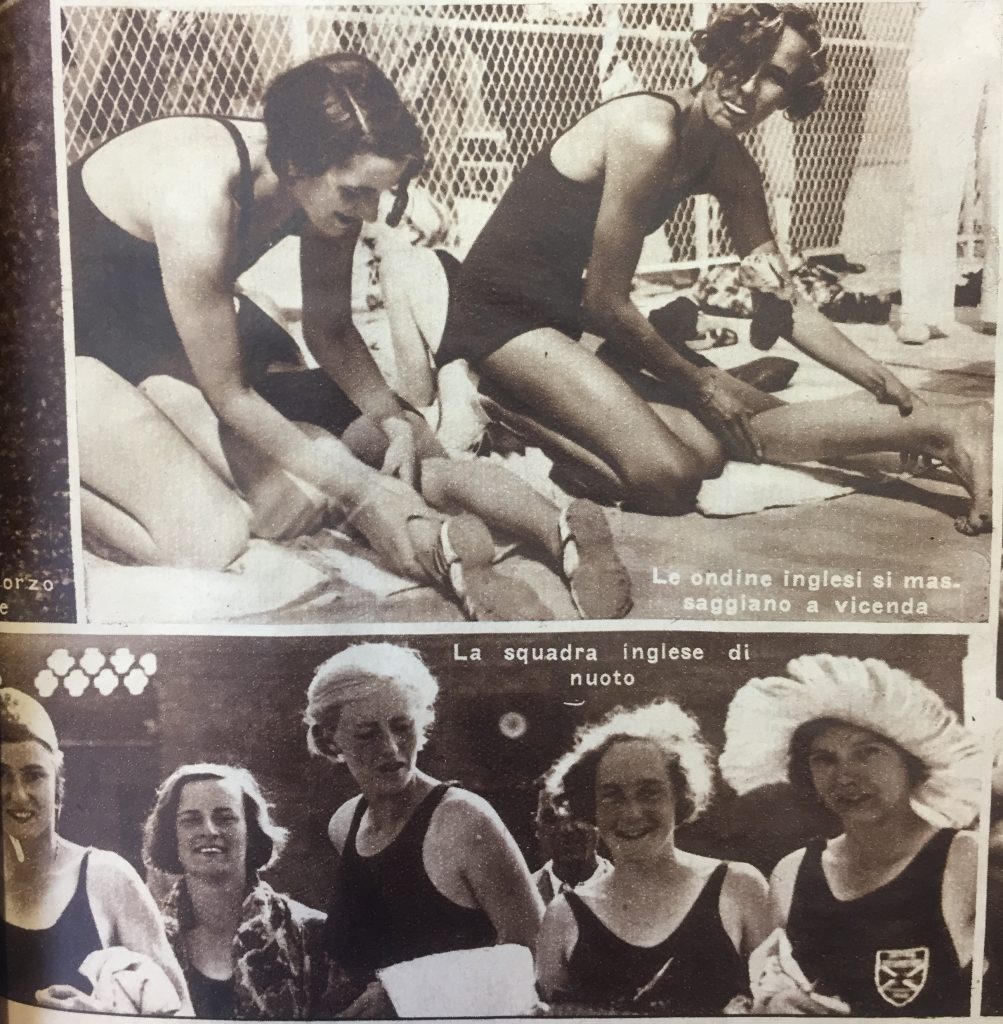

In the last photo we can see the male and female swimmers together: the women are wearing tracksuits rather than swimsuits, yet they are shown together with their male colleagues, a very important symbolic conquest. We should remember that the swimming female body was still considered quite scandalous for a lot of contemporary readers; on the other hand, Italian press published a lot of picture in which Hollywood stars were depicted participating in sports, including swimming (see https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1020331217386917888 ) – an excellent example of the paradoxical social policy of Italian Fascism, which was willing both to preserve the conservative values and to modernize Italy. We also see this double standard (foreign women vs. Italian women) in the publishing of swimmers’ photo from Turin: in particular, the Italian photographers took many picture of the British athletes, who seemed, to the Italians to be very uninhibited about their sporting body, particularly in the pictures depicting massage.

British swimmers Westropp and Slater

Source: La Donna, October 1933, p. 21

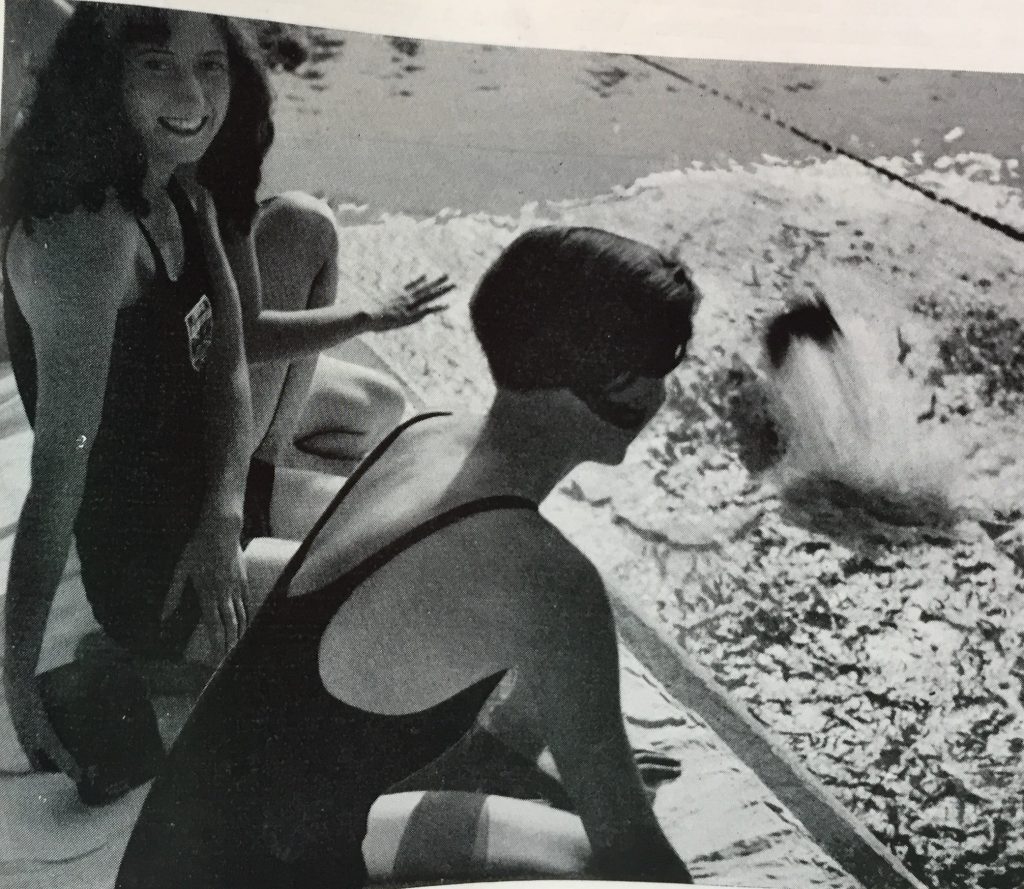

Swimmers watching their team-mates during competition

Source: La Donna, October 1933, p. 22

British swimmer Bennett and her masseur

Source: La Donna, October 1933, p. 23

The first caption says ‘The British ondine massaging each other‘

Source: Illustrazione del Popolo, 17/09/1933, p. 11.

Let’s move to the depiction of the bodies of the Italian swimmers. La Domenica Sportiva was quite daring in publishing the whole body of Hilde Prekop, the winner of the 100m breaststroke gold medal, as if she was a Hollywood star, under the title of an article devoted to IUG; the more conservative L’Illustrazione Italiana decided to publish only her face, cutting the photo to show just the head and shoulders …

- Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 17/09/1933, p. 2.

- Source: L’Illustrazione Italiana, 17 September 1933, p. 429

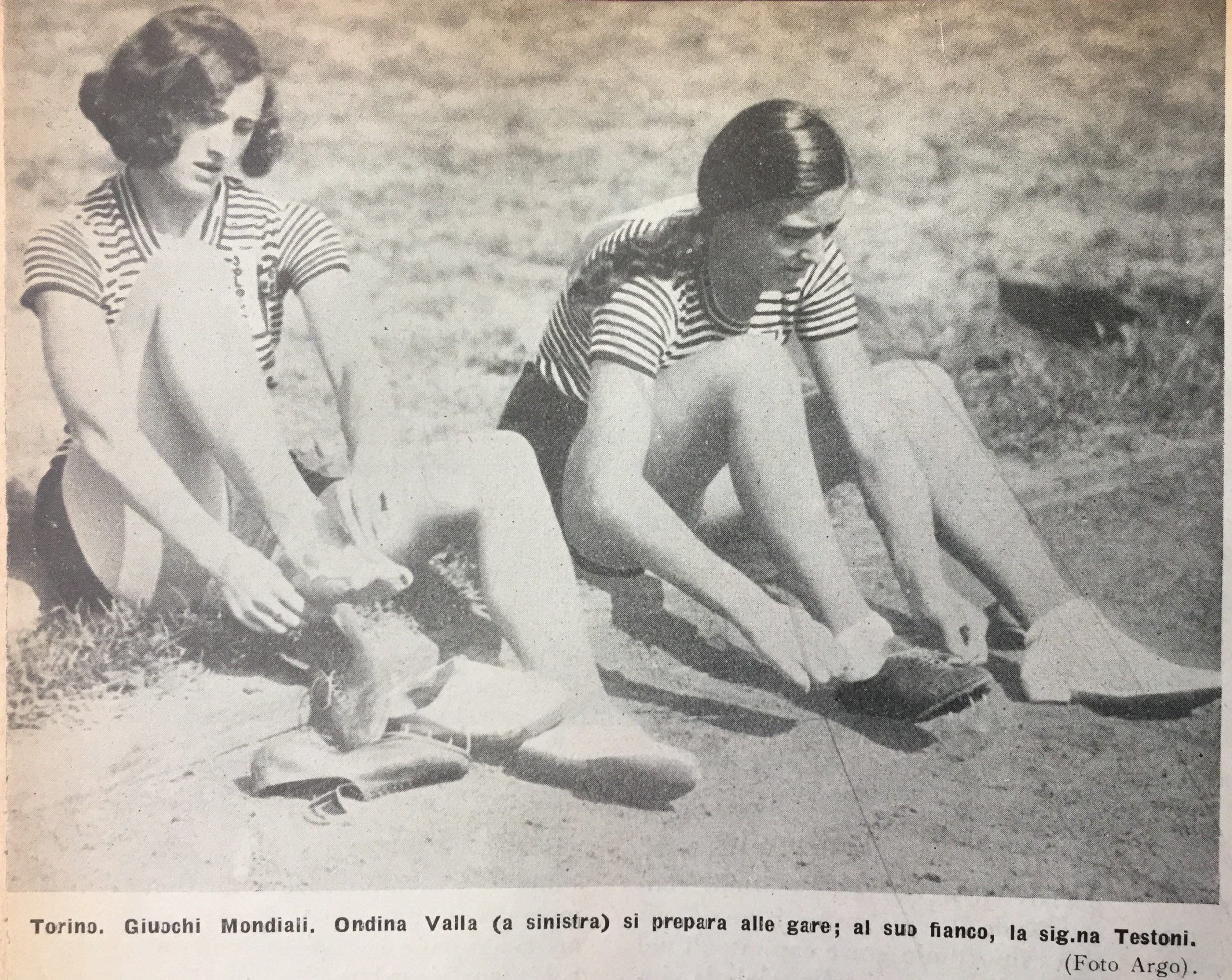

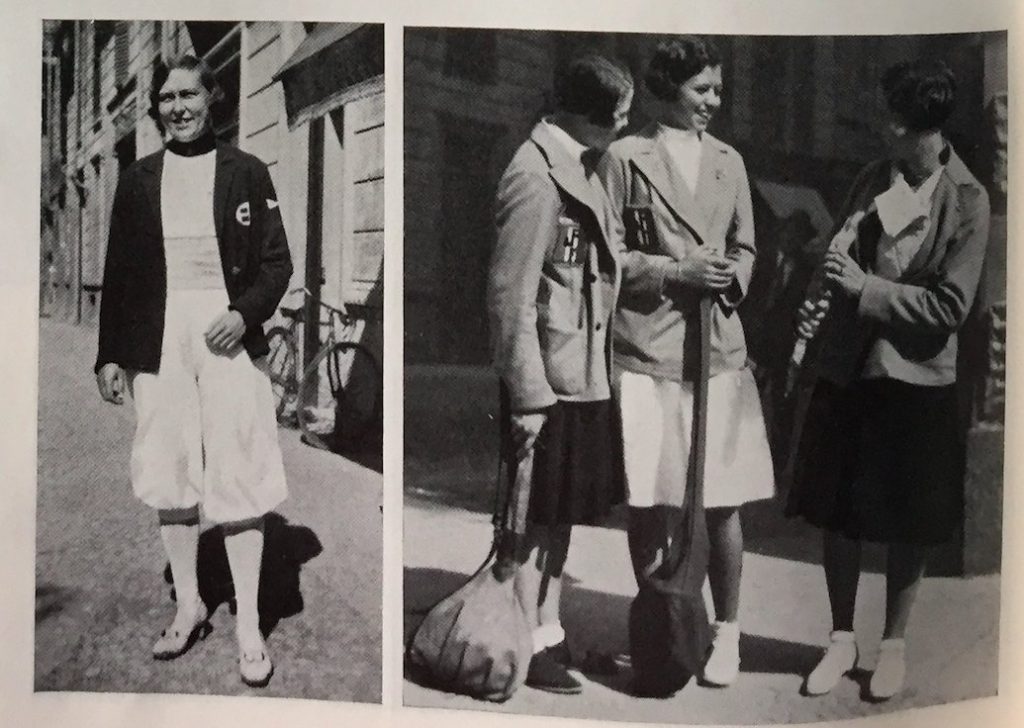

This iconographical question was shared by the female athletics too. Just one month on from the IUG, a controversy arose in Italy when L’Osservatore Romano (the Vatican Italian-language journal), accused the Italian press of being very lascivious in publishing pictures of athletes and swimmers. The ‘iconographical sin’ of women athletes was, of course, in the wearing of shorts: for this reason, high jump photographs (such as the one we have previously seen showing Ondina Valla in action) were judged scandalous by many. Other types of images charged with such ‘immorality’ were those where athletes were captured in the process of changing their shoes, due to the seemingly ‘immoral’ image of legs and shorts:

- Source: La Rivista Illustrata Del Popolo D’Italia, September 1933, p. 65

- Source: L’Illustrazione Gran Sport, Settembre 1933, p. 22

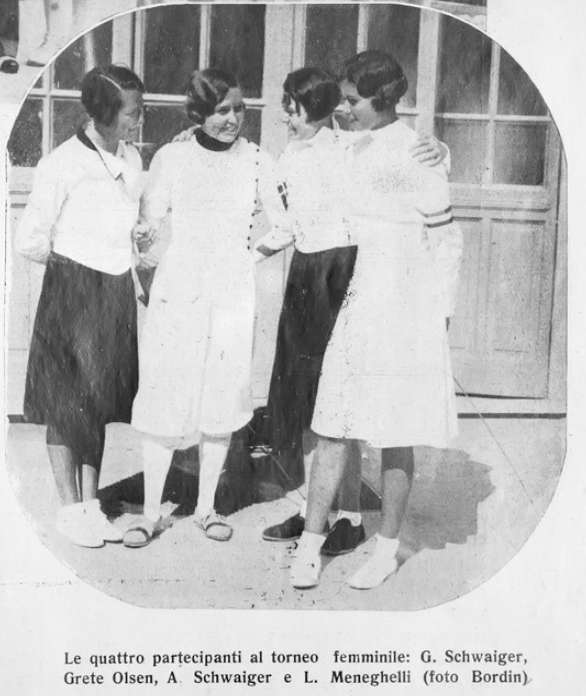

Let’s return to the sports events. In tennis, Ivana Orlandini won the gold medal against another Italian opponent (they had both easily defeated British opponents in the semi-finals). The Italian team was defeated by Latvia in women’s basketball. In the fencing tournament, the three Italian girls (including Anita Schweiger, about whom Angela Stelitano is publishing very shortly a monograph) could not gain an advantage over the one foreign opponent, Grete Olsen of Denmark.

Grete Olsen (Denmark); Schwaiger sisters and Letizia Meneghelli

Source: La Donna, October 1933, p. 22

The four fencers

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, September 1933, p. 17

A clip from the foil event, and a picture of Grete Olsen

The Italian press wrote that her victory was deserved

Source: Illustrazione del Popolo, 17/09/1933, p.10.

As we have seen, the 1933 Turin IUG was a huge propaganda occasion: the regime was able to turn a ‘neutral’ international sports event into a Fascist one, exploiting the presence of athletes from all over the world. Then, it won a lot of events using professional athletes instead of amateur university ones: an impropriety used above all in the women’s events. Anything went, in order to gain international prestige, useful to show to the Italian audience, thus proving that the new Fascist Italy was ready to become a real international power in sport. Yet, as an old Italian proverb says, “Le bugie hanno le gambe corte” (‘lies have short legs’, meaning ‘no lie live forever’): time would expose this propaganda operation. As Gherardo Bonini had recently underlined in his Breve profilo storico del nuoto femminile italiano dall’Ottocento ad oggi, no Italian female swimmer from 1927 to 1945 ever raced in the European Championship or the Olympic Games. Above all, one year later the absolute hero of the 1933 Turin IUG, Ondina Valla, winner of 4 gold medals, would take part in a complete fiasco at the 1934 London Women’s World Games, knocking down the hurdles (see https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/gender-and-sport/when-ondina-knocked-over-two-obstacles-the-italian-fiasco-at-the-1934-womens-world-games-in-london/ ).

Article of © Marco Giani

For more pictures from 1933 International University Games, see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1048553863102521344

For more pictures about 1930’s Italian women’s swimming, see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1078643110740148224

For more pictures about 1933 Italian women’s athletics, see:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1050429049041022976

For an article about the iconographical representation of the female athletic body in 1930’s Italy, see:

https://ojs.lib.unideb.hu/itde/article/view/4667

For an article about the late 1933 polemic by L’Osservatore Romano about the female athletic body: