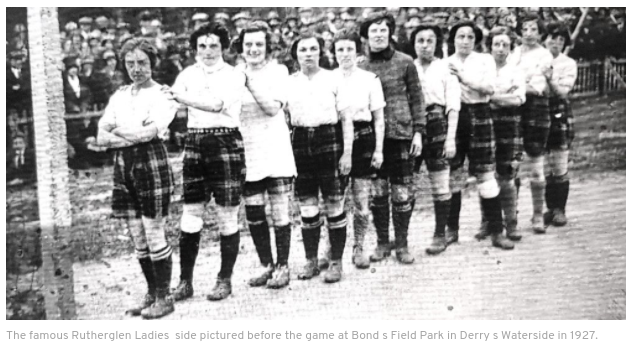

Rutherglen/ J H Kelly XI in Derry in May 1927

Source: Bigger McDonald Collection

Rutherglen Ladies FC, Mr James H Kelly & Sadie Smith

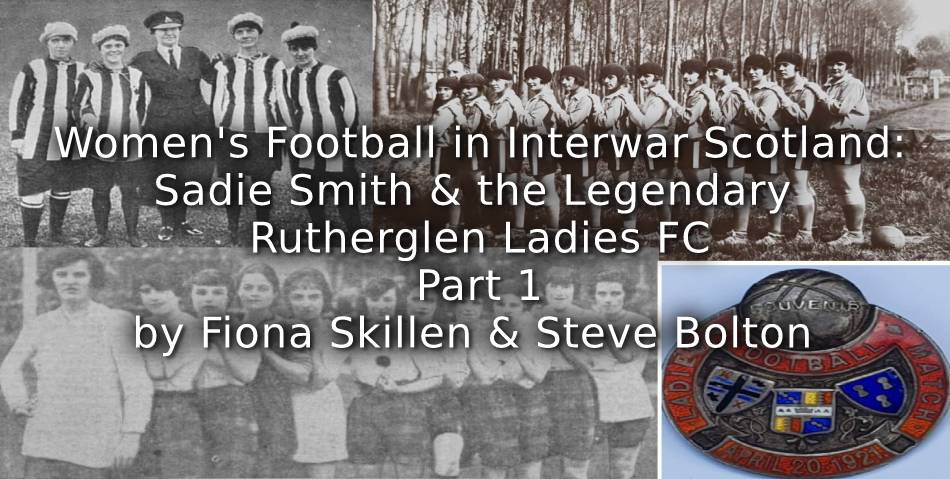

Women’s football in Scotland has a magnificent and largely overlooked history of over 100 years. In 2021 we are approaching the 100th anniversary of the infamous English FA ban. Whilst the Scottish FA did not formally implement a ban until almost two decades later, the shock waves of the English ban had implications for the growth and development of the women’s game north of the border. Recent international success for the national women’s team has meant there is, for the first time, a real interest in the origins of the game in Scotland. In this article we will be exploring the rich, yet overlooked developments of the interwar years.

From our preliminary research it seems that the two decades of the interwar years are quite different. The latter half of the 1930s saw a magnificent growth in Scottish Women’s Football ranging from ‘married’ vs ‘single’ at Orkney Summer Fetes to, by 1939, the dominance of the (mostly) unbeaten Edinburgh City Ladies FC. By contrast after an initial peak in the early 1920s, a link to the munitionette teams which sprang up during the war, the late 1920s were arguably the ‘doldrums’ for women’s football, something which seems to have been mirrored across the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, with one unique exception. Just like the small Gaulish village in the stories of Asterix, there was one legendary team of women carrying the torch for women’s football in the late 1920s: Rutherglen Ladies FC, a team from the greater Glasgow area, with their superstar Captain Sadie Smith who deserve recognition for their unique place in history. This is our tribute to those magnificent Scottish women footballers.

‘Folk Football’ vs Modern Football

Before we explore the story of Rutherglen Ladies it is important to understand a little of the context in which they developed. There are no ‘De Jure’ standards for classifying women’s football. ‘Folk Football’ is a useful umbrella term to describe anything that isn’t formal modern football as we would understand it today and includes mixed games, fancy dress games, married vs single at annual fetes, etc. This is not to devalue the social worth of these games, in fact these types of women’s football have been played for centuries across Scotland and look to have peaked during the interwar years. But we must differentiate between the various different types of footballing events which were taking place, often in the same period and location, to help identify the growth of ‘serious’ or formalised women’s football. The formalised football, a forerunner to the modern game, was given a tremendous, some would argue seismic, boost due to the first World War.

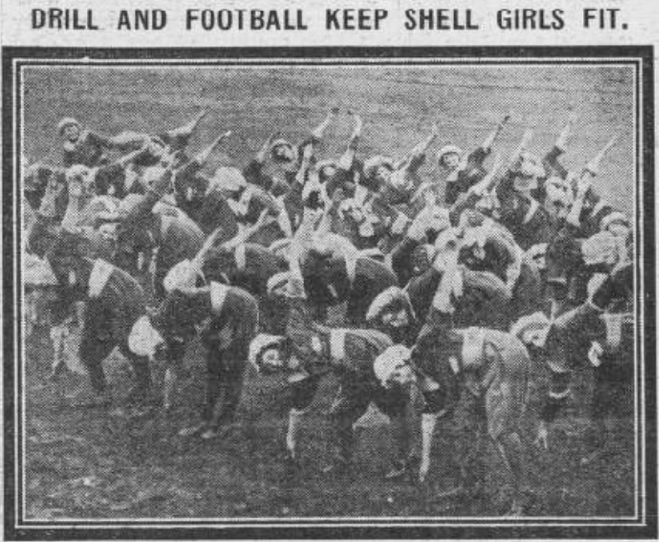

Between 1914 and 1918 female employment in the UK rose from 2.18 million to 2.97 million, it is estimated that 700,000 were ‘munitionettes’ employed in the manufacture of munitions for the war, while other heavy industries also accounted for large numbers as they were also employing higher levels of women than ever before. Those employed were often girls as young as 14 or 15 who were given unprecedented independence away from home and parental control: particularly fathers and brothers. The government was extremely worried about what these young girls would do with their spare time and sport was amongst the activities which was encouraged.

WW1 and The ‘Munitionettes’

Munitionettes with their ‘Welfare Superintendent’

Source: BNA Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News Sat 5th October p26)

In the early part of the war the Portsmouth Ladies played a large number of high profile, nationally reported ‘folk’ matches against male military and wounded teams. The men would have their arms tied behind their backs and would sportingly lose. The interest generated by these games and the huge need to raise funds for war charities gradually led to more serious munitionettes’ games being played at high profile fundraising events. This led to the ‘golden’ season of 1917-1918 when teams like the unbeaten Sterling Ladies of Dagenham were playing 20 or more games. In Scotland teams developed at many of the factories focused on war work such as Beardmorese engineering factory, Monifieth Foundries, Mossend Munitions and the country’s largest munition’s complex at EastRiggs near Gretna.

Source: BNA Sunday Mirror 18th February 1918

The outbreak of the war brought with it a number of opportunities for women. They were encouraged to take up employment outside of the home and domestic service in larger numbers than ever before to replace the men who had gone off to fight. These new roles, a significant proportion of which were in factories, exposed women to new leisure pursuits, one of which was football. While the sport was probably not new to women as there is evidence of female fans attending games before the war, playing it themselves was for most a novelty, having been seen as an exclusively masculine pursuit. In the wartime factories, however, women were encouraged to play in their breaks, in part to improve their general fitness, which was necessary for the heavy manual labour they were now expected to undertake. As a result of these local ‘kick abouts’ teams began to form, and just as their male predecessors had done, these factories teams began to play against each at local sports days and then at higher profile and more formalised events all across Scotland.

Women Footballers in Glasgow in 1914

Source: BNA Daily Record Wednesday 18 February 1914

One of the most prolific factory providers of women’s teams in this period was William Beardmore’s, an engineering manufacturer who specialized in the production of artillery shells, warships, airplanes and other heavy metal products in this period, with factories across the Glasgow area. But the interest in football spread to women across Scotland as can be seen by this note from Dundee.

‘Some of our female munition workers are becoming keen devotees of football. On Magdalen Green way several of them can be seen nightly playing vigorously, attired in the garb which has become so familiar in the case of females since the outbreak of war. Some of them are very adept at the game, and can dodge their male opponents with remarkable dexterity.’

Dundee People’s Journal, Saturday 11 May 1918, p6

Wartime ‘Internationals’

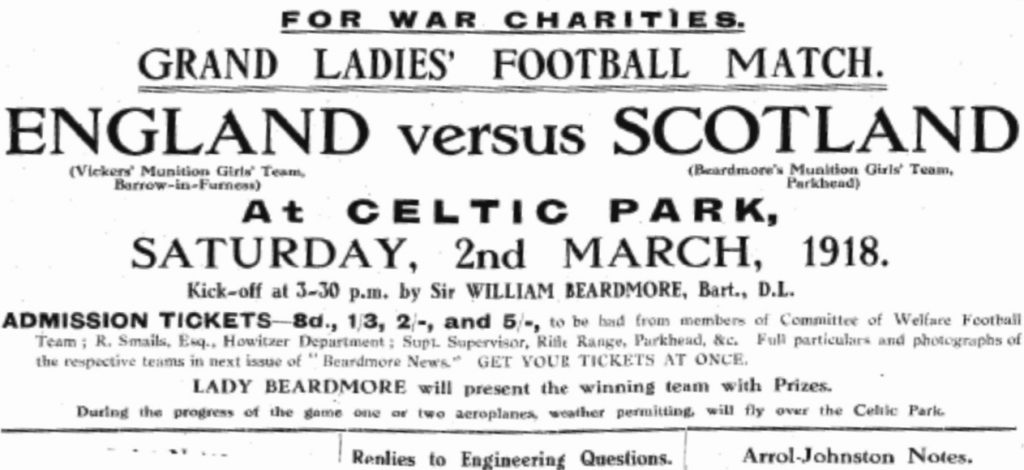

Vickers’ Munitions Girls’ Team vs Beardmore’s Munitions Girls’ Team

Celtic Park, Glasgow 1918

Source: Beardmore News February 1918

Raising Money for War Charities

The first formal UK competition amongst these ‘munitionette’ teams took place in August 1917 at Celtic Park in Glasgow. The munitionette competitions developed across the country. In addition, international matches also took place, with a Scotland vs England match taking place in March 1918 at Celtic Park. Scotland lost 4-0 but won the return leg in Barrow a couple of weeks later. The teams for these ‘international’ matches were recruited from the factory teams at Beardmores and Vickers’-Maxim Munitions Factory. These matches were played to raise money for war charities. The 1918 ‘international’ at Celtic Park match for example raised £200 (Glasgow Bulletin, 3rd March 1918).

1921 December 5 – The Sword of Damocles Falls in England

On 20th April 1921 the second and third greatest teams of the 1920-1921 Season met in front of 30,000 at Birmingham City’s football ground St Andrews. There had been a massive growth in women’s football due to their ability to raise substantial amounts of money for charity through charging entry fees to their matches. Attending these matches was viewed by the public as both enjoyable and patriotic. Many of the charities supported by these games provided vital services to those physically and mentally injured during the conflict. However, whilst the generation of income for charity was a benevolent act on the part of the footballers it was to ultimately prove a factor in their undoing, in England at least.

Lizzy Ashcroft’s Debut Medal 1921

Source: Lizzy Ashcroft Collection

The Birmingham Daily Gazette reported on Tuesday the 19th April 1921: “Out of the 28 ladies’ teams now playing in Great Britain, St Helens is second only to Dick Kerr’s.” There were a few more games in May but it was the tail end of the season. Going forward to the ‘ban’ season 1921-1922 Constance Waller the articulate voice of the Huddersfield Atalanta Ladies FC is quoted in December as stating that there were 150 teams in the country. It is debatable as to how recent and stable these teams were but it is easy to see that the growth from around 30 to 150 teams in a couple of months was the cause of significant concern to the English Football Association (FA). To nobody’s surprise they introduced a formal ban on December 5th. In principle the ban prevented women from playing on FA affiliated grounds and male referees and players were forbidden to referee or coach women’s teams. The justification for such severe sanctions was given as concerns over money irregularities and the damage the game could do to women’s bodies. There was little evidence to support either claim. Regardless, the impact of the ban, and publicity which accompanied it, was to fundamentally undermine the growth and development of the women’s game in England for almost fifty years.

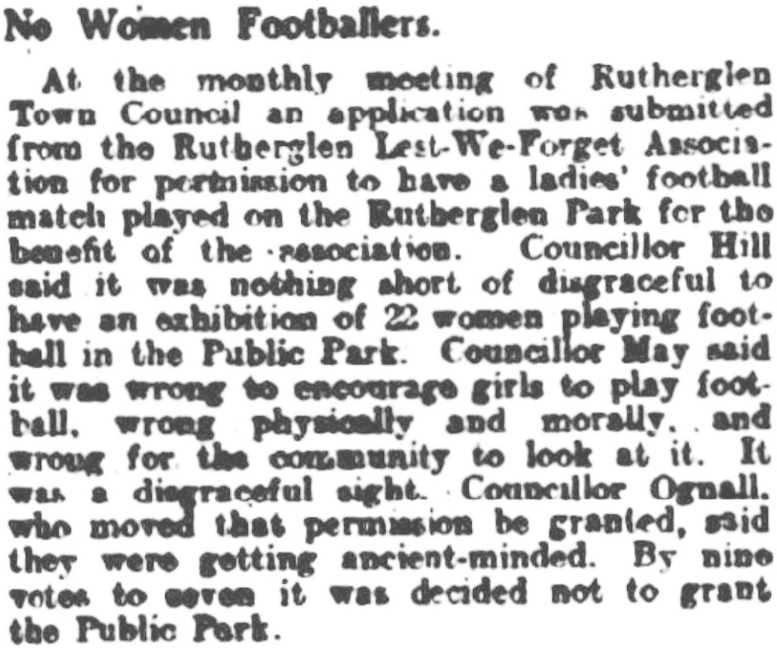

The shockwaves of this ban were felt across the world as other football associations followed England’s lead. It is interesting to note that Scotland did not implement an equivalent formal ban until 1947, although they were less than encouraging towards the women’s game prior to this. The FA’s ban was reported widely in Scotland and commented on in both its national and local presses, with journalists speculating whether women in Scotland should also face similar restrictions. Despite all of this, some magnificent women’s teams continued and even flourished.

Scotland Reacts to the FA Ban

The women’s game had proved popular during the war. The number of teams playing had increased dramatically and the numbers attending matches were significant. As one journalist explained in 1918,

‘At Fir Park, Motherwell, a few weeks ago a crowd of 15,000 assembled at a munition factory sports meeting, and quite 10,000 turned up at Ibrox Park, Glasgow, a couple of Saturdays! … There were no star performers at either gathering, no promise broken records epoch-making feats to draw the public. But the outstanding novelty, the event responsible for this paragraph, was the ladies’ football match.’

That is not to say that everyone was happy about this. Indeed, there was a feeling amongst some, perhaps even the Scottish Football Association (SFA), that perhaps it was only the unique conditions of the war which permitted these women’s endeavours to be accepted by the general public and that the end of the war would bring these pursuits to a natural end.

‘Whether garbed in a musquash coat or in khaki overalls the woman worker is the heroine of the moment, and I suppose that explains there being no change in the attitude towards her when she changes into jersey and pants, and is admired for doing gracefully what was reckoned disgraceful twenty years ago. We are getting on and no mistake, but I wonder how the woman worker-footballer will fare a year or so hence when she will take her place on the rope in the tug-of-war between male and female labour in munition and other factories.‘

Bellshill Speaker Fri 13th July 1918.

There were those who certainly thought the women’s game in Scotland deserved to follow the FA’s example. A lengthy letter to the Aberdeen Press and Journal concluded:

‘To sum up, as a mere ” game” in friendly rivalry and with a reasonable time limit, girls’ play might be encouraged, but feminine football, as a public spectacle, could only be deplorable? We have tolerated lady players at theatrical matches, we have seen the munitions girls seeking healthy exercise in chasing the elusive leather with zeal and wholehearted effort that we may have felt was a little misdirected though we accepted it under war conditions — but these were merely by way of diversion. Nobody except perhaps the girls themselves are deluded into thinking that this sort of football was sport, and certainly the ” soccer” enthusiast would not admit its right to the name.’

Anon, Aberdeen Press and Journal, Mon 17 May 1920.

The introduction of the FA Ban in December 1921 was reported across Scotland. On the 6th of December, the day after the introduction of the ban under the title ‘Measures to prevent women footballers’ The Glasgow Herald printed full sections of the FA resolution and offered support for its introduction. Similarly, Scottish Sport on the same day focused primarily on the medical justifications for the adoption of this resolution ‘as they consider the game unsuitable for females’ and noted that they believed for this reason, the SFA ‘would appear to have a good deal of support’ were they to introduce an equivalent set of restrictions. The Aberdeen Daily Journal went further, in an article about the ban entitled ‘Football Freaks’ the journalist goes as far as to compare women footballers to performing dogs! The letters pages of local papers in the weeks that followed seemed to be just as much in favour of a Scottish ban as the journalists.

‘Female football has experienced a rude shock. The football Association have pronounced against it a strict and stern ban. With all my heart I say ‘here here!’(…) the camera never lies – and one only needs to look at a photograph of one of these games in progress to realise how Utterly graceless, awkward and ungainly are the players engaged. Apart altogether from the questions of health and physical strain, the game played is only a travesty of football, it never could be anything else.’

Anon, Letters Page, The Southern Reporter (Edinburgh), Dec 15 1921

1922 Rutherglen Ladies Emerge

Champion Lady Footballers

Source: Dundee Evening Telegraph, 31st August 1926

In spite of support in the press for restrictions to women’s football our research suggests that local women’s teams continued to play across Scotland after the war and even FA ban. One team which has emerged as central to our research into the development of the game in Scotland in this period, due to its prolific number of games and press coverage, is the Rutherglen Ladies. We are currently researching the exact origins of the Rutherglen Ladies team. We are tracing information about their manager J.H Kelly and the role his wider family played in the running of the team. What we have found already is that by 1922 they were established enough to be playing regularly in front of substantial crowds across the Central Belt of Scotland. Six of the games involving Rutherglen were reported upon in 1922.

Rutherglen (J H Kelly XI) 5 v 5 Falkirk Iron Co Men

Source: BNA Falkirk Herald Saturday 5th August 1922 p9

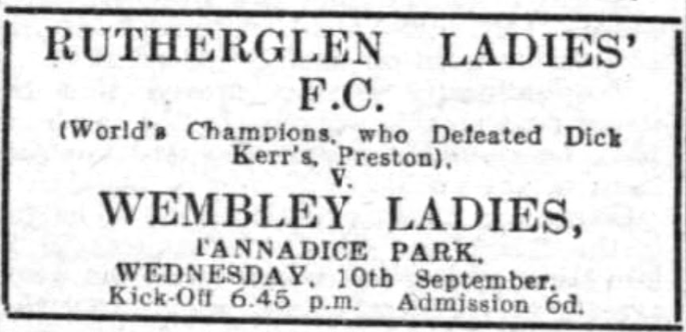

On Monday 2 May between two and three thousand people watched Rutherglen play Edinburgh at Berwick-Upon-Tweed. The local newspaper quoted that ‘Only one player had any idea about football and that was Smith on the outside position on the left wing’. In the post ban years one of the greatest challenges when anyone went through the expensive and challenging process of putting together, organising, funding and training a women’s football team there still remained one fundamental question: who to play? The high profile matches played by Rutherglen (aka J H Kelly’s XI) in 1922 show that serious games against men’s teams were regularly played by this formidable team of Glaswegian women. Most ‘mixed’ football over the years has been treated by the media with disdain because it fell squarely into the definition of ‘folk’ football where for instance the men would have their arms tied behind their backs and would sportingly lose. This appears not to be the case for Rutherglen and this would be an excellent way of improving their football. Games of note include the game in the advert above and at least two more high profile games against Blackridge Men and Longcroft Ex-Servicemen. On Saturday 14th October Rutherglen lost to the magnificent Heys Brewery Bradford Ladies 3 – 0 at Shawfield Park, Glasgow. This is a creditable score against one of the few English teams to survive beyond the ban 1921. Rutherglen were on the up but still had some improving to do.

Source: Edinburgh Evening News Wednesday 16 May 1923

It is worth noting that whilst hundreds and sometimes even thousands turned out to their games not everyone was supportive of Rutherglen Ladies. This article from the Edinburgh Evening News above nicely highlights the conflict which the team and others like it had to face when trying to secure places to play. While there was no formal ban of women’s football there were still significant informal, often social, barriers to their playing.

Rutherglen Ladies FC, World Champions?

In their publicity materials Rutherglen Ladies were billed as an ‘international team’ and after 1923 as ‘World Champions’, but just where did those claims come from? To understand them we need to look at other well-known teams of the time.

1925 Postcard of ‘World Champion’ Dick Kerr Ladies

Source: Lizzy Ashcroft Collection

As 1922 turned into 1923 the glamour of the October 1922 USA tour had started to fade and the Dick Kerr Ladies of Preston were facing the realities of post-ban football. In 1923 three of their superstars moved off. Jennie Harris joined Heys Brewery Bradford Ladies and Florrie Redford followed her friend Carmen Pomies back to France. Alfred Frankland the Dick Kerr Ladies manager was going to need all of his marketing genius to keep the club going. On Saturday 22 September 1923 the Dick Kerr Ladies lost 1-0 to Stoke Ladies at Colne Cricket Club in what is thought to be the last game of the great Stoke Ladies FC.

Two weeks earlier the Rutherglen Ladies FC defeated the Dick Kerr Ladies 2-0 at Shawfield Park, Glasgow. In a clever managerial and marketing move manager J H Kelly then promoted his team the Rutherglen Ladies as the ‘World Champions’ because they had defeated the Dick Kerr Ladies. There were similar claims to a ‘World Championship’ in 1934 when the formidable Belgium Ladies toured against the Dick Kerr Ladies having defeated the combined French teams for two or three years. There were also similar claims in 1939 when the Edinburgh City Ladies defeated the Dick Kerr Ladies (Preston Ladies) 5 – 2 on Saturday 17 June in Edinburgh. Some authors promote this and forget to mention that the Dick Kerr Ladies defeated the same Edinburgh City Ladies 3 – 0 in Middlesbrough just over three weeks later on Tuesday 11 July… In reality, the whole idea of labelling a team ‘World Champions’ was simply a common and effective marketing ploy to attract large crowds and in turn raise money for worthy causes.

Three Truly Great Teams – Dick Kerr Ladies, Femina Sport and Rutherglen Ladies FC?

Femina Sport of Paris: Madeleine Bracquemond (4th left), Carmen Pomies (right)

Source: Lizzy Ashcroft Collection

Women’s football on the continent flourished during the 1920s, particularly in France and Belgium. Women’s football in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland struggled in the 1920s but began to flourish in the 1930s and this was in no small way due to the activities of three legendary teams in the 1920s. The second of these teams is the magnificent Femina Sport of Paris and their legendary Captain Carmen Pomies. It is doubtful if the Dick Kerr Ladies could have kept going without the Femina/French tours in 1925, 1932, 1933, 1935, 1936, 1937 and 1938. The 1925 tour by Femina Sport was one of the most important tours in women’s football history. Generally things were not going well for the Dick Kerr Ladies and Alfred Frankland decided to try a ‘massive throw of the dice’ by getting Femina over to tour. A very, very strong French side came over. At one point in and around the Paris region there were over 18 sides. Femina Sport had their own Stadium, Stade Elisabeth and a strong DKL side was put together for a high profile series of (hopefully) money-spinning games. Games were played at Herne Hill, Padiham, Mellor, Fallowfield, Hyde, Kilmarnock, Dumfries, Belfast, Chorley and finally a last match at Herne Hill. The DKL won 7, drew 2 and lost one. This tour included two high profile matches in Scotland. This ultimately very successful strategy was used by Alfred Frankland throughout the 1930s and indeed after World War II. J H Kelly of Rutherglen did not have this strategy available so he had to find another way.

1923 Cinema Girls – Some Decent Female Local Opposition is found

In 1923 Rutherglen continued to play against men’s sides but at least 6 high profile games have been found against the ‘Cinema Girls’. The games were closely contested affairs and were played at locations such as Lanark, Kilsyth, Linlithgow, Bellshill and Carluke. Each of these venues was within 10-30 miles of Rutherglen and most were on train lines. This would suggest that they weren’t travelling too far for games.

The media reporting of these games was generally very positive and in at least one game they attracted a crowd of 2,000 spectators. So far, little has been discovered about this interesting team of Scottish women footballers and they do not appear to have played beyond 1923. The most likely current hypothesis is that they were associated with a local cinema/cinema chain which were very, very numerous and popular in the 1920s and could explain the ‘Cinema Girl’s’ matches mentioned above.

Rutherglen (World’s Champions) 3 v 0 Wembley Ladies

Source: BNA Dundee Evening Telegraph Tuesday 9th September 1924 p4

On Friday 14th September 1923 at Shawfield Park the Rutherglen Ladies defeated the Dick Kerr Ladies 2 – 0. Very few details of the game have emerged. James Kelly’s granddaughter Dorothy Connor whose mother was the team Mascot and whose Aunty was the trainer testifies that Lizzie Wilson, Eileen Earls and the 18 year old prodigy Molly Seaton from Northern Ireland played that day. She also states that Jean Kemp, Betty Kemp and Mary Gray of Edinburgh were in the team. It appears that J H Kelly had outmanoeuvred Alfred Frankland in securing ‘star’ players for his team.

Amateur Footballers – Lizzy Ashcroft and Lily Parr

Lizzy (5ft 8in) + Lily in 1931

Source: Lizzy Ashcroft Collection

Granny Was A Footballer

Lily Parr is the most famous woman footballer in history. She was the first woman footballer to be inducted into the English National Football Museum Hall of Fame in 2002. She played for the famous Dick Kerr Ladies of Preston from 1920 to 1951.

Steve Bolton is one of the co-authors of this article and has a personal interest. His granny Lizzy Ashcroft joined the Dick Kerr Ladies in April 1923 and it is highly likely that she played in the 2-0 defeat by Rutherglen. “If my granny played in a team that was beaten by a team containing Molly Seaton and Sadie Smith then I couldn’t be more proud.”

Conclusion: Interwar Women’s Football in Scotland

In Part 1 of this article we have traced some of the development of the women’s game in Scotland from the First World War through to the early 1920s. We have explored our initial findings around the Rutherglen Ladies and shone a light on their rise to prominence. In the second part of this article we will explore in more detail their remarkable 1927 and 1928 tours, the fame of some of their players, the fate of the team in the 1930s and their modern legacy.

In both parts of our article we have presented some of our initial research findings. Women’s football in Scotland in the early Twentieth Century has been under-researched. Little is known about the development of the game in the interwar period and we hope that our work will help to shine a light on the Scottish experience. Our work thus far has thrown up a number of surprises as we have highlighted here, from the development of Rutherglen Ladies to the role of stars such as Sadie Smith. These stories have been missing from the historiography of both the British and the Scottish women’s game.

It is not possible to do justice to this rich and important topic in two short articles. The authors have gone to every effort to make this article as accurate as possible, but our research is ongoing. We have used this article as an opportunity to make informed conclusions and hypotheses based on the research we have done to date. Writing about women’s football from 100 years ago is full of pitfalls. It is likely that further evidence will arise and these theories will have to be adapted or even corrected. This is the spirit in which this article is presented.

Article © of Dr Fiona Skillen and Steve Bolton

To read Part 2 Click HERE

Hi both

Very interesting article. Looking forward to part 2.

Steve, have you come across any links with other sports, particularly hockey, as we have found in England?

Mark Evans

Hi Mark

Thanks for the positive post. I wish that you had asked this before we looked at the 180 or so articles… As this project develops we will keep an eye out for any hockey references and copy you in

Gosh, amazing. I have been following the Scotland National Women’s team since 2002, I have a match programme vs Belgium.

As erstwhile ‘spokesman for the Tartan Army’ I have promoted the team continuously. There is a small band of us who are now avid supporters, I was in the Netherlands, we lost 6-0 to The Auld Enemy, the Euros & the Argentina a match in Paris which as is tradition we turned a glorious 3-0 lead into glorious disaster. 4 of us travelled to Albania in Nov 2019. 6 Scots were in a crowd of 62, I counted the fans.

We were so looking forward to qualifying for England, what a joy that would have been, so many would have travelled.

Despite the coverage there exists so many disparaging comments from friends and Scottish fans, shame on them.

Excellent post, thank you

faz.lombard@gmail.com