Break out the strawberries and cream, sun hats and umbrellas, it’s the second week of Wimbledon 2021. The top tennis players from around the world are back on court at SW19 to play on the hallowed grass after the cancelation of The Championships in 2020. Among the great athletes hungry to win a Wimbledon title are the top wheelchair tennis professionals. We consider the opportunities that existed for disabled people to play tennis historically before moving on to outline the development of the wheelchair game and highlighting a few of Britain’s record-breaking players.

‘Tennis in Algeria’

Source: Peter Maxton, From Palm to Power: The Evolution of the Racket (2008, Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum)

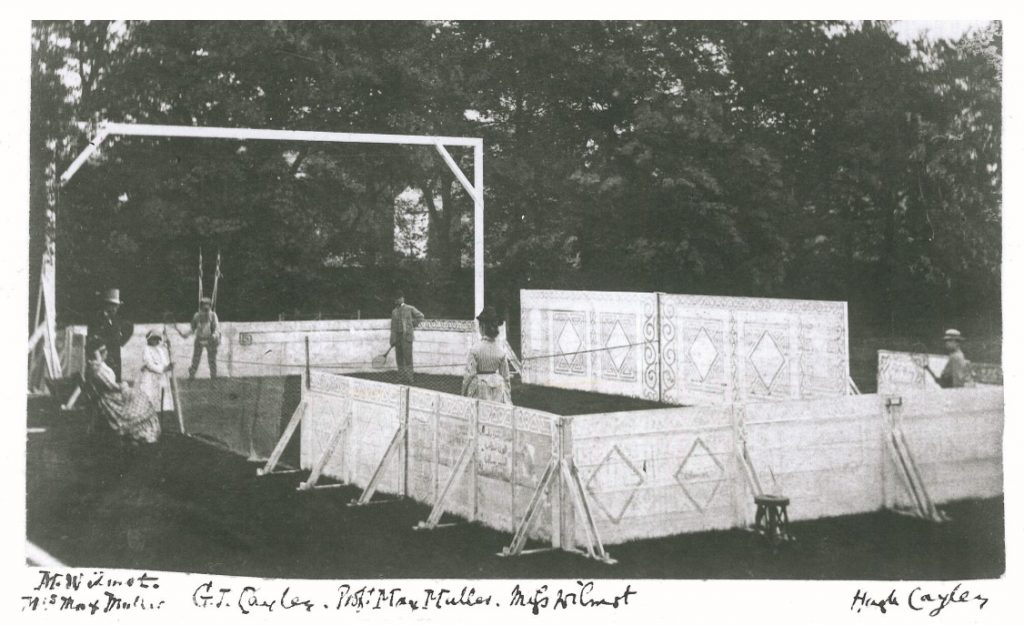

For researchers interested in the history of tennis, this photograph is a super intriguing find. Although it’s reminiscent of what is now well known about the playing of tennis as a ‘garden’ lawn game before the coming of the first – and now longest running – tournament in the world, The Championships, Wimbledon, what it depicts seems to be at odds with our perception of attitudes to disability in the late nineteenth century. It demanded that we find out more about George J. Cayley – the man who is identified as wearing a harness to play tennis. Knowing his name brings clarity to our understanding of why and how he came to be suspended from a braced structure, one which hopefully rendered him mobile by means of a hidden runner along the length of the crossbar. The Cayleys were an established Yorkshire family, descended through a baronetcy created in 1661. George J’s grandfather was another George, Sir George Cayley, the gifted aeronautical engineer and inventor, whom George J. reputedly helped with glider test flights. According to descendent, Michael Cayley

‘In 1870 he [George J.] went to live in Algiers to try and improve his health. There he played tennis as long as his health permitted …’

Whilst we can’t be certain that the idea to contrive the tennis apparatus was George J’s alone, it is plausible to say that he had some hand in contriving it to get a game of tennis in. Moreover, if we apply more recent understandings of attitudes to disabilities in society, we can equate George J. Cayley’s thinking as not simply inventive, but firmly on the side of defying social attitudes which in the Victorian period would have almost certainly preferred to see him confined to an invalid’s chair on the sidelines of the court, as opposed to being an active player on it. That Cayley is known to have worked on the development of tennis rackets (with carpenter and cabinet maker William Button Maslen) and wrote an article for The Edinburgh Review published in 1875 entitled ‘Lusio Pilaris and Lawn Tennis’, marks him out as more than a casual recreational player; but rather an early proponent of a game which by 1877 had gathered sufficient traction in society to justify inaugurating a Gentlemen’s Singles tournament at the All England Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club, the courts located at the aptly named Nursery Road in Wimbledon.

Cayley may well have been gratified by this positive development for lawn tennis, however, he died the following year aged 52, so didn’t even live to see the incorporation of the Gentlemen’s Doubles and Ladies Singles events in 1884. Mixed Doubles, the game typically equated with the privatised sociability of garden lawns (with which the Cayley family were obviously well acquainted) came into the Wimbledon programme in 1913, along with the Ladies Doubles.

Did Cayley have the kind of mind that might have imagined the effective adaptation of what came to be known as wheelchairs to bring a new version of the game into being and ultimately to Wimbledon? We like to think he did – although he might have been disappointed that the innovation required to make that inclusion possible would take little short of a century to achieve and, moreover, it would not be the product of British inventiveness.

Physical recreation and sport at Stoke Mandeville Hospital: why not tennis?

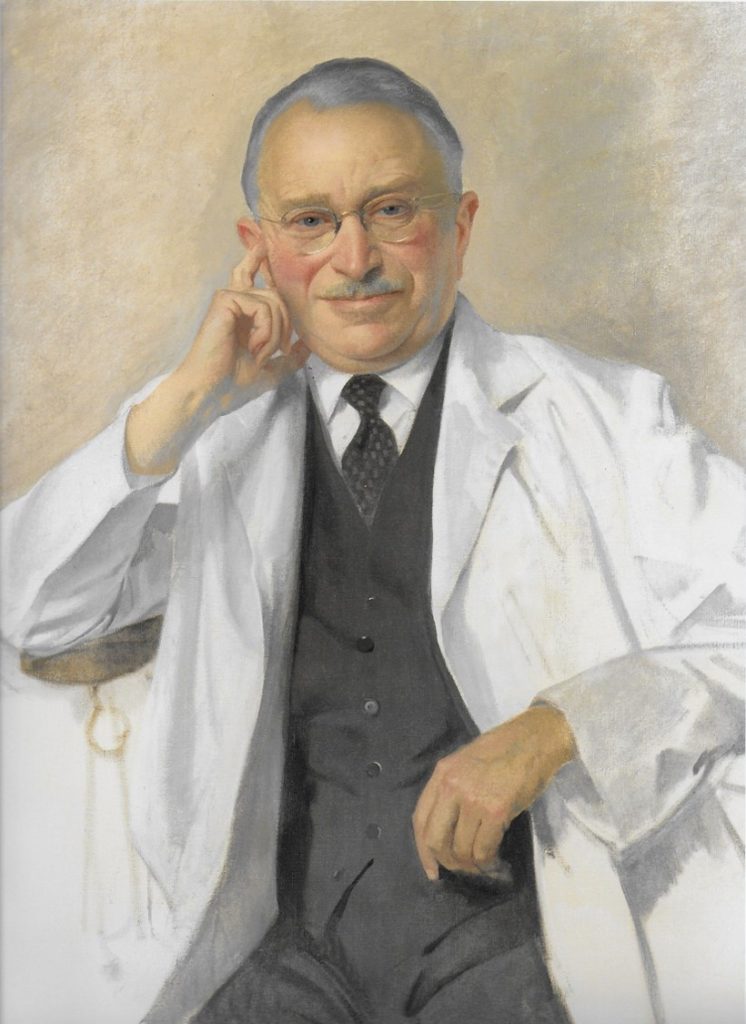

Given that wheelchair tennis was not officially seen in the world of sport before the 1970s, an obvious point of exploration is the celebrated work of Dr Ludwig Guttmann at the National Spinal Injuries Centre, sited at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, England. Founded in 1944, the physical activities adopted within his rehabilitation programme to improve the quality of life for those living with spinal cord injury (paraplegia) are becoming increasingly well documented. Sporting activities were initially used in the treatment of injured service personnel during and after the Second World War. Subsequently disabled people from overseas also went to Stoke Mandeville to benefit from the renowned programme. Whilst patients could play a range of games including darts, snooker, punch-ball, skittles and table tennis, the activities typically cited as illustrative examples of the ground – breaking approach are the sports of archery and wheelchair basketball.

Portrait image Dr Ludwig Guttmann

By kind permission of Eva Loeffler OBE & The National Paralympic Heritage Trust

Archery was favoured because it enabled patients to enter the world of local clubs and, significantly, enjoy competition with non-disabled players. And it was archery too that took centre stage as the demonstration sport at the first competitive event organised to coincide with the opening of the 1948 London Olympic Games. It is, however, the routine identification of wheelchair basketball in Guttmann’s programme but the lack of reference to the court-based game of tennis which gives us speculative pause for thought. This is because the introduction of wheelchair basketball at the 1955 Stoke Mandeville Games and archive film footage from the 1960s suggests players were using wheelchairs that could be manoeuvred sufficiently to facilitate a more dynamic sporting experience than archery, or even wheelchair netball which seems to have been sidelined in favour of basketball. Thus, it is at least fair to ask the question why not tennis?

Image reproduced by kind Permission of The National Paralympic Heritage Trust & WheelPower Archive, Stoke Mandeville

A possible reason is indicated by Nikki Wedgewood who has found that patients themselves were influential through attempts to devise their own wheelchair sports and, on seeing the positive effect of their choices, Dr Guttmann conceded to include them even though he was notoriously autocratic in the management of patient rehabilitation. As time went on, Stoke Mandeville was also responding to international developments in sport and it should be noted that wheelchair basketball was already played from 1945 onwards in the USA, initially at administration hospitals for war veterans. Deeper research is needed to establish whether tennis was ever considered, tried, and abandoned by patients or never thought of at all. One thing is certain, it is not listed as a competitive discipline in any of the Stoke Mandeville Games which took place between 1948 – 1959.

On the one hand, by the time disability sport appeared on the world stage in 1960 at Rome via the 9th Annual International Stoke Mandeville Games (the International Olympic Committee sanctioned the term ‘Paralympic Games’ in 1984) the fact that wheelchair tennis had not been developed might be viewed as a missed opportunity – albeit one that sat alongside many other ‘missing’ sports for disabled people at the time. On the other, that wheelchair tennis did not feature in the mix of pursuits catalysed out of Stoke Mandeville (or elsewhere for that matter) can be seen as hardly relevant in light of the platform the 1960 games provided for the future development of disability sports, associated events and, in turn, wider acceptance of and opportunities for participation. Indeed, in the years that followed, wheelchair tennis itself evolved to become a robust addition to the Paralympic programme, debuting at Seoul in 1988 as a demonstration event. There, men’s and women’s singles matches were showcased and wheelchair tennis subsequently became an official Paralympic sport at the Barcelona Games in 1992.

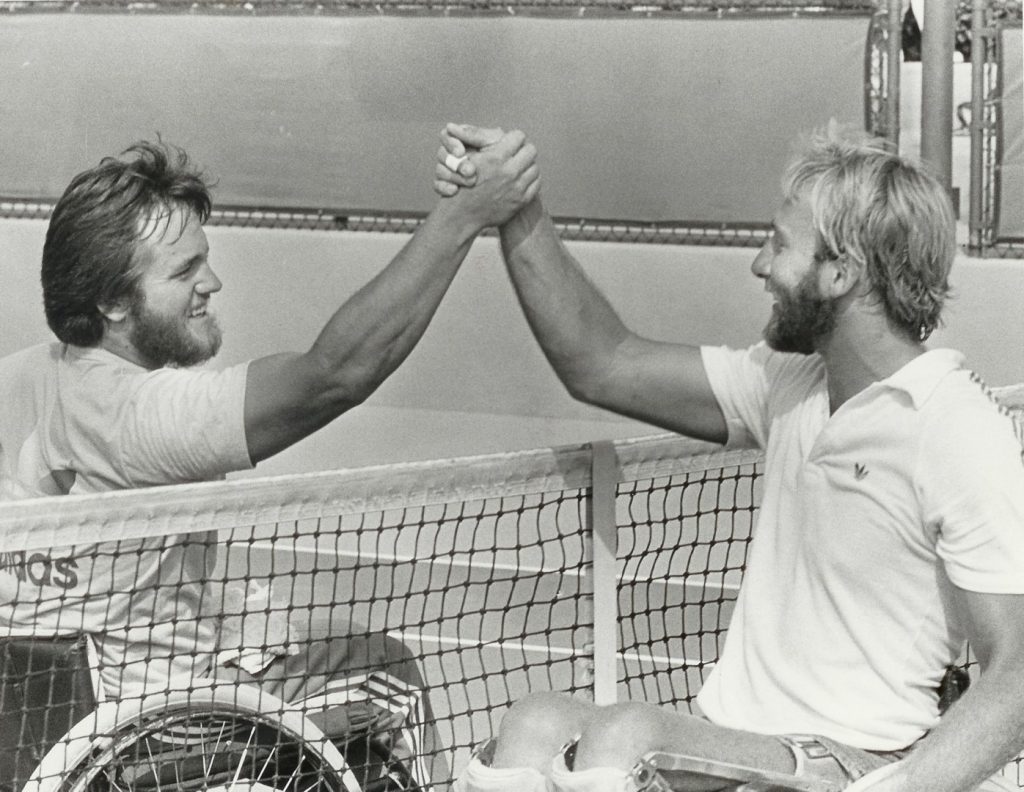

At that first Paralympic tournament doubles matches were also played and are notable on two counts: firstly, the triumph of Monique van der Bosch and Chantal Vandierendonck which marked the beginning of the Netherlands run on gold which to date is undefeated. Secondly, the winners of the men’s doubles were a combo from the United States – Brad Parks and Randy Snow. It is perhaps no coincidence that these gold medallists came from the USA where the sport of wheelchair tennis was not only well established but had been invented. Someone integral to that invention, as well as the sport’s further rapid development was Brad Parks.

Wheelchair tennis: from foundation to integration

In tennis circles the name of Brad Parks has become synonymous with the wheelchair game. Another figure equally integral to the invention and early development of it but who generally receives little credit is Jeff Minnebraker. This is surprising, given that the circumstances of their meeting can perhaps be counted as one of the most serendipitous moments in sports history.

In early 1976, Parks severed his spinal cord during warm-up for a freestyle aerial skiing competition at the Park City resort, Utah. Necessarily entering a period of rehabilitation and adjustment, on holiday with his parents Parks was struck by an article he read about Los Angeles – based recreational therapist Jeff Minnebraker who encouraged patients to play wheelchair sports. On that basis, Parks tried tennis there and then. In her official history of the wheelchair game, Sarah Bunting confirms that it was Minnebraker ‘who had [first] been playing tennis in a wheelchair experimenting with two bounces of the ball using a customised chair he had built out of square tubing.’ (2001: 10). In a remarkable twist of fate, on return from his holiday Parks discovered that the new recreational therapist at his hospital was none other than Jeff Minnebraker.

The meeting of these two was destined to underpin a rapid course of development for the nascent game. Before the year was out, Minnebraker had featured in a short documentary film entitled Get It Together which focused on his ‘new experience’ of being disabled after a road accident – except this was not a descriptor he was willing to accept: mastery of his bespoke ‘chair’ filmed at home, in the workplace, and briefly in a scene playing tennis with Brad Parks projected the message that self-sufficiency was possible to achieve, even in a society acknowledged to be generally inhospitable to wheelchair users.

Randy Snow (L) & Brad Parks (R)

US Open Wheelchair Tennis Championships in Irvine, California (1981)

Copyright Brad Parks and by kind permission of AELTC

It seems that Minnebraker found a kindred spirit in Parks: during 1977 the pair attended a tennis college in Mission Viejo and then began to promote the wheelchair game via camps and exhibitions on the west coast of the USA. This was the year they decided wheelchair tennis should differ from the pedestrian game in just one respect: what became known as the two-bounce rule. In short, wheelchair tennis would otherwise be played on a standard court and so was more similar than different to its pedestrian counterpart. This rendered it eminently appealing to those who played, as well as readily intelligible to those who watched. It also meant that games could incorporate both wheelchair and pedestrian players. With the rules decided, it was ready to be taken to a wider audience and the first ever tournament with 20 participants was hosted locally by the LA City Parks and Recreation Department.

Thereafter Parks picked up the pace and began coaching pedestrian players, practiced with the women’s tennis teams at the University of California, and promoted the game with Minnebreaker via a programme of camps, clinics and exhibitions. In 1980 they were invited to Australia to introduce the game there, but thereafter it was Brad Parks who became the face of wheelchair tennis, not only because of the tournaments he went on to win until retirement from competition in 1992, but because he drove the institutionalisation and profile of the game forward.

Front cover of ‘Tennis in a wheelchair’ by Brad Parks

For example, the National Foundation of Wheelchair Tennis was founded in 1980 as the organising body in the USA, with Parks serving as President. This coincided with the publication of his book Tennis in A Wheelchair (endorsed by the United States Tennis Association), and the inaugural US Open Wheelchair Tennis Championships. In 1988 the coming of the International Wheelchair Federation (IWF) underpinned the game’s inclusion in the Paralympic Games, but perhaps most significant was the place gained at the table of the International Tennis Federation (ITF) in 1998, with the International Wheelchair Tennis Association retaining independence but taking an advisory role. That the game went from strength to strength in the space of 20 years and attracted sponsorship to support national and international tournaments from the likes of Everest & Jennings (the world’s biggest wheelchair manufacturer) and NEC (Japan’s leading communications and technology company) marks it as one of the most successful disability sports to emerge in the twentieth century – a position it maintains to this day.

In 2010 Brad Parks’ contribution to wheelchair tennis was recognised through his induction into the Tennis Hall of Fame and since then his contribution has been regularly celebrated. The movement he spearheaded which saw wheelchair tennis go from park play to global game is nothing short of remarkable, but we would argue that the name of Jeff Minnebraker also deserves to feature more consistently in the foundation story than is currently the case. This is because Minnebraker identified the viability of tennis as a game for people living with paraplegia, he began to formulate rules which were ultimately adopted, contributed to grassroots development and, perhaps more importantly, led the way on adaptation of chairs – including Parks own – to maximise efficiency of game play.

Although Minnebraker disappears from existing accounts of wheelchair tennis as it continued to grow, he did not stop investing his efforts into the design and production of lightweight wheelchairs which could be constructed to end users’ specifications. Branded as the Quadra, this could be understood as Minnebraker’s nod to the Independent Living Movement which emerged out of California in the 1960s. It was led by a group of students from Berkeley known as ‘The Rolling Quads’ who advocated that people with disabilities knew their own needs best – and on that basis could provide solutions to the barriers society presented to them. Although chair technology has evolved since Minnebraker applied his aviation and engineering skills to it, not least in the use of body imaging for the production of individual sports models, the vibrancy of the wheelchair game today is easily identifiable with that played well before the turn of the twenty-first century.

There is, however, still a long way to go before wheelchair tennis professionals attain the consistency of coverage that their pedestrian counterparts do for their athletic achievements, at least across the UK media.

Wheelchair Tennis at Wimbledon

There are two annual events on the UK sporting calendar where wheelchair athletes garner significant ‘live’ annual coverage: the London Marathon and The Championships, Wimbledon. Racers were welcomed into the Marathon via a parallel event in 1983, just two years after the inaugural race. With wheelchair tennis becoming very well established through regular international tournaments by the 1990s, it was only a matter of time before it became incorporated into the Wimbledon schedule.

Michaël Jeremiasz from France and Britain’s Jayant Mistry

Copyright AELTC

Wheelchair Doubles matches have been held since 2001 and in 2005 Jayant Mistry was the first British player to win the Gentlemen’s title alongside Michaël Jérémiasz from France. This made him the first British man to win a men’s title at Wimbledon since Fred Perry in 1936, yet it is unlikely that many in the UK are aware of it.

Yui Kamiji / Jordanne Whiley

Copyright AELTC

Similarly, many would be unaware that Britain’s most successful (wheelchair) tennis player is Jordanne Whiley, winner of 12 Grand Slam titles and two Paralympic medals. Whiley excels as a doubles player and has won the Wimbledon title four times with her regular partner from Japan, Yui Kamiji. In 2014 the partnership also saw Whiley become the first British player to win at the Australian Open, the Roland Garros (French Open), Wimbledon and the US Open in a single year, thereby achieving a Calendar Year Slam.

Alfie Hewett & Gordon Reid

Copyright AELTC

Wheelchair Singles events are a relatively recent addition at Wimbledon and Gordon Reid was first to win on home turf in 2016. Reid has an impressive doubles partnership with Alfie Hewett at The Championships (winning in 2016, 2017 and 2018), but their recent success at the 2021 French Open saw them reported by the BBC as making history by becoming the first men’s partnership to win 11 Grand Slams – breaking a record held since 1905 by British brothers Laurie and Reggie Doherty.

Andy Lapthorne & Dylan Alcott

Copyright AELTC

Quad Singles and Doubles events, where a player has limited mobility in 3 or 4 limbs came onto the SW19 programme in 2019. Andy Lapthorne missed out on raising the singles trophy to Australian Dylan Alcott, but together they went on to win the inaugural Quads Wheelchair Doubles Final.

It is fair to say that wheelchair athletes have been far more successful both at Wimbledon and on the international stage than the names we typically associate with the British game. As we write, the media is focusing attention on the highs and lows of established and rising ‘tennis’ stars at this year’s Championships, let’s hope the achievements of our wheelchair players past and present are equally celebrated and elevated as the second week unfolds.

Article © of Carol Osborne and Emma Traherne

Further Information:

The Championships, Wimbledon 2021 run from Monday 28th June – Sunday 11th July. The wheelchair tennis tournament will be played during week commencing Monday 5th July. The Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum, located at the All England Lawn Tennis Club (AELTC) opened a new permanent display examining the history of wheelchair tennis in March 2020. The Museum is currently open to those holding a ticket for The Championships and will reopen to the public later this summer.

Cited sources:

Sarah Bunting (2001) More Than Tennis: The first 25 years of wheelchair tennis. London: The International Tennis Federation.

Michael Cayley, ‘George John Cayley and lawn tennis’ (October 11, 2017) https://cayleyfamilyhistory.wordpress.com/2017/10/11/george-john-cayley-and-lawn-tennis/

Nikki Wedgewood, cited in Matthew Klugman & Rob Hess (2016) ‘Towards a Pre-History of Disability Sport in Victoria, Australia’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 33:14, pp.1669-1681.