The best Italian and South Tyrolean literature on winter sports does not mention the great history of luge and bobsleigh on the natural track that had Vipiteno/Sterzing as a backdrop before the creation of the International luge federation (FIL) in 1957. The natural-track bobsleigh has irreversibly waned, while since 1970 the luge has found its space with it’s own international championships and an autonomous World Cup.

Sterzing, located in South Tyrol, was one of the most active centers of these two sports. The path of its Jaufen road which linked the little sites of Kalch/Calice and Gasteig/Casateia, about seven kilometres long, became the scene of exciting challenges, engaging the entire city, for which luge was not only a game, but also a pleasure, entertainment, sport, athletic and technical challenge, as well as a cultural moment of social aggregation and identification for people of every age.

Since its foundation in 1907, the Winter sport association of Sterzing organized numerous luge and bobsleigh events on the Jaufen, that from 1912 to 1914 hosted four Austrian (three bobsleigh and one luge) Championships on the natural track. After World War I, South Tyrol became Italian, and Sterzing immersed into a completely different political, social and sporting reality.

The intertwining of individual and family sport stories involved some formidable women champions, whose deeds were hidden more than those of their male colleagues. These stories unfolded in a difficult historical context for the inhabitants of South Tyrol.

- Skeleton in Jöring

Fascist violence assaulted the region of Bozen/Bolzano, of which Sterzing is still a part, even before October 1922 when Mussolini took power. By 1919 the races on the Jaufen had resumed. In South Tyrol (Alto Adige for Italy) Fascism operated a forced nationalization of the German minority, whose sense of belonging was strong, as were the links with North Tyrol and with the German area, especially Southern Bavaria: exchanges, visits and contacts were frequent and intense. The luge and bobsleigh, popular in these regions, cemented this commonality.

- The start in Kalch of the Turin Prize, 1921

Born in Innsbruck, one of the protagonists of the races on the Jaufen was Antonie Toni Kelderer, a good winter athlete since 1909, in the 1920s she was an over-thirty, expert athlete, as well as her daughter Lotte Embacher (born in 1908) who was preparing to become an elite athlete, and Anna Baur, who, in 1920, had married the gifted athlete, Josef Gartner. Anna would compete until 1939, interspersing work, career and seven pregnancies. Since bobsleigh grew in an aristocratic environment, women could compete. The International Bobsleigh Federation (FIBT) led by the English and French, created in 1923 did not officially admit women, but they were accepted in Central Europe. The longest bobsleigh could hold five competitors. Women often drove shorter two-person bobs. In luge, in addition to the women’s single-seater event, the two-seater race allowed mixed or even a two-woman crew. In 1955 a mixed two-seater team competed in the European Championships. In the local Central Europe races, sometimes the mixed luge enjoyed an official championship. In 1926, two women, the Austrian Hantsch and Germany’s Scheuch, won the two-seater German Championship. In almost every local and national Championships, participation was not limited to a single nationality.

-

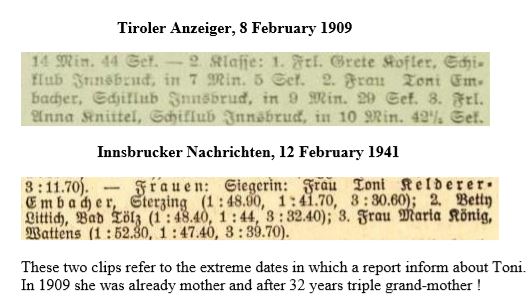

These two newspaper cuttings show the first and last dates of Toni’s competitive life.

By 1909 she was already a mother and 32 years later a 3 x grandmother

This promiscuous and internationalist reality was unknown in Italy and viewed with suspicion by Fascist sport authorities. Luge was little practiced by other clubs outside the region of Bozen, and almost exclusively on the artificial track, as well as bobsleigh, whose main centre was Cortina d’Ampezzo.

-

Lotte Embacher in 1929

Photograph by Ernst & Cezanek

Despite authoritarian measures, Fascism made some practical compromises. Furthermore, the prestige of Sterzing tobogganers was growing. In 1927, Anna dominated the Austrian Luge Championships, while her husband won the two-man event together with Zingerle, who in turn won the men’s single. In 1929, taking advantage of job opportunities, Lotte moved to Semmering, near Vienna, where she won the European title. Was she still an Italian citizen or had the practices to become Austrian come to an end? Fascism never claimed that victory. After organizing many prestigious competitions since 1921, in 1931 the Italian authorities granted Sterzing the hosting of the Italian Bobsleigh Championships which were also filmed by the Istituto Luce. Toni competed and her younger daughter Herta was part of the crew, which came 7th.

-

Feanz Zingerle

Photograph by Hajek Ludwig

In the 1934 Championships, three women were included in the crew of one bobsled, among them, Maria Rimanni. In reality her surname was Maria Riedmann, but Fascism had “invited” the population to Italianize their surnames. This hateful practice was mandatory for administrators, and Maria worked in the municipality. In 1935 the ladies came in 2nd place. They were part of the town’s elite, so no one could how bar them.

In 1935 the European Luge Championships had become official under the aegis of FIBT, of which Italy was part. In 1937, Sterzing also hosted the Italian Luge Championships. Maria won the two-seater event with Luis Hofer. In 1938, Anna returned to the scene and won the Italian single title, 11 years after her victory in the Austrian Championships. On the men’s side, only Zingerle accomplished the same achievement. February 5, 1939 saw the Italian Championship, where Toni, now over 50 years old and a grandmother, drove an all-woman sled to victory and the Italian title. Anna Hofer acted as brake and the other team-members were Clelia Pucci and Klara Stötter, as well as Maria. In the luge events, Maria won the two-seater, but an unbridled Toni beat her in the singles, after a hard fought competition.

- Anna and Maria Seeber

Officially, citing the outbreak of war and the consequent restriction of competitions to Olympic sports, Fascism abolished all tobogganing on the natural track. Toni was not happy, but in February 1941 in Igls, near Innsbruck won the German title for over-forty class.

After the war, Sterzing resumed competitions, and organized, once again, the Italian Luge Championships, which was open to all international competitors. Lotte, who returned to Italy after 1945, won many honours, retiring in 1958 at fifty years old, sadly for her, unable to match her mother’s winning longevity. Maybe, once artificial-track luge became part of the Olympic programme, it contributed to the demise of the fascinating, if not troubled history of the Jaufen competitions, an era characterized by extraordinary women.

- Italy, Europe Championships, 1951

Article © Gherardo Bonini