Please cite this article as:

Martin, D. James Searles and the Revival of the Barclay Match, In Day, D. (ed), Pedestrianism (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2014), 111-132.

______________________________________________________________

James Searles and the Revival of the Barclay Match

Derek Martin

______________________________________________________________

Introduction

Captain Barclay’s 1809 feat on Newmarket Heath – walking one mile every hour for 1,000 successive hours – is well documented.[1] The immense distance involved, the endurance required and the inexorable striking of the clock for 41 days and 16 hours combined to give the event an almost mythic status and the accepted version of history was that it had never been repeated. But a strange form of sporting amnesia had fallen over the later history of the Barclay Match. James Searles was one of several working class pedestrians who not only equalled the Captain’s achievement, but surpassed it in distance and difficulty and, in some cases at least, developed the event into a major money-making spectacle. Barclay was a gentleman amateur, but it is difficult to believe that someone who wagers 1,000 guineas is motivated purely by the sporting challenge. His successors were working pedestrians, who no doubt had their own professional pride in their achievements, but to whom it was in essence another job of work.

There were in the first half of the nineteenth century two waves of Barclay Match enthusiasm. The climax of the second revival was in 1852, when a dozen Barclay Matches or variants were performed throughout the country. The pedestrians of the 1850s were not starting from a blank sheet; it seems likely that they were using traditions or knowledge derived from pedestrians active in the years following the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Barclayists after Captain Barclay

In the decade after Waterloo at least six pedestrians completed a Barclay Match, and in some cases went beyond it. They were all recognised pedestrians with credentials in ultra-distance events. The Barclay Match was well known to them, but they did not regard it as the almost impossible feat of popular imagination – many were capable of events that were typically 50 to 70 miles a day and up to 1,500 miles in total.

Josiah Eaton

Eaton was the pioneer. Born in 1770, he was a baker by trade and (by his own account) a successful and prosperous one, who walked out of admiration for Captain Barclay and ‘more from emulation than the desire for gain.’[2] In a short but intensive career, between 1815 and 1818, he walked several long distance matches. He is the first authenticated Barclayist after Barclay himself. In November 1815, he walked 1,100 miles in 1,100 successive hours on the road, from the Hare and Billet at Blackheath, thus adding four days and four hours to the event. [3] This started the practice of adding difficulties to the standard Barclay event. In the summer of 1816 he did another 1,100 mile walk at the same venue, this time adding the condition that he would finish every mile at no later than 20 minutes after the hour.[4]

Despite this, it was said that Captain Barclay and ‘sporting men generally’ would not accept that his feat had been equalled or surpassed. It was to settle these doubts once and for all that Eaton and his backers agreed that Eaton would attempt 2,000 half miles in 2,000 successive half hours.[5] The match came off at Brixton Causeway, beginning on 23 October 1816, and went well until the final morning, 5 December, when Eaton stopped, having completed 1,998 half miles and deliberately refused to walk the remaining four half miles. In his cantankerous way he said that he had been ‘deceived’ by his backer and that therefore he had sabotaged the event – the precise circumstances remain a mystery.[6]

In 1818 he announced the most radical development of the Barclay Match yet contemplated – he would walk a quarter mile each quarter of an hour for exactly 42 days, i.e. 1,008 miles in 4,032 separate starts. This would reduce radically the time for rest to ten minutes or less at a time. Not surprisingly, the betting was 5 to 1 against him. The venue was Stowmarket in Suffolk, a meadow opposite the Pot of Flowers Inn. He finished triumphantly in the afternoon of Tuesday 23 June, and was chaired through the town ‘in the presence of 2,000 of the most respectable gentlemen in the county of Suffolk.’[7]

Henry Barnet

In July 1816, whilst Josiah Eaton was walking 1,100 miles at Blackheath, Henry Barnet walked 1,000 miles at the rate of 1½ miles each hour at the Duke’s Head, Wall End, Barking in Essex. This was yet another variant, a ‘fast’ Barclay Match, completed in a mere 28 days. We do not know anything of Barnet’s antecedents. He had reached the advanced age of sixty-nine[8] and it seems likely that he had some prior athletic background because he had been training under Daniel Mendoza, who had been one of the dominating figures in the prize ring in the 1790s. Mendoza and ‘some sporting gentlemen, eminent in the circles of pugilism,’ acted as his handlers during the event.[9]

John Wright

John Wright was another veteran. He was born in 1765. [10] He was a tailor by trade who served many years in the army. Between 1817 and 1824 he was an itinerant professional. We can identify more than thirty long-distance walks that he did in this period, ranging from 40 miles up to the 1,200 miles which he walked in twenty days at Blenheim Gardens in Gloucester.[11] In 1822 he did his only known Barclay Match, at the Fives Court Alley Bowling Green at Sheffield. He attracted considerable betting interest, not least from the 7th Dragoon Guards stationed nearby – one officer of the officers of the Guards, who won £400 on his performance is said to have presented him with £50 of his winnings.[12]

Robert Skipper

Robert Skipper was born about 1787.[13] He was one of the greatest ultra-distance professionals of the nineteenth century. He began his pedestrian career, when he was an ostler at the Barley Mow Inn in Norwich, by running against stage coaches and in his first formal event, in 1816, walked 50 miles in 11 hours 10 minutes at the Prussia Gardens.[14] Thereafter he was engaged fairly constantly in pedestrian challenges until 1842. He performed more than a dozen walks of 1,000 miles or more in his career, for example, 1,500 miles at the rate of 50 miles a day for thirty days from The Mouth of the Nile public house in Copenhagen Street in Worcester to the Lamb in Cheltenham and back each day in 1823.[15] He did two variants of the Barclay Match, both in 1822. In June that year he as said to have had walked, at Newmarket, the longest Barclay Match yet achieved – 1,200 miles in 1,200 hours.[16] In October he walked 1,000 miles in 1,000 half hours.[17]

Robert Cootes

Cootes (or Coates) was another professional with a long career. Born in 1806, he was active from the early 1820s for more than thirty years, walking and running constantly in all varieties of pedestrian contests in Britain, Ireland and France. He even attempted an aquatic version of the Barclay Match, rowing a boat on the Thames one mile each hour, in 1828. [18] He was still around to play a small part in the Barclay revival of the early 1850s. In 1828 he achieved the longest version of the Barclay Match up to that time – 1,250 miles at a mile and a quarter each hour, at the gardens of the Green Man Tea Gardens on the Kent Road in London.[19] The following year he did a ‘short’ Barclay Match, 1,000 miles in 500 hours.[20]

Authentication

From the end of the 1820s the Barclay Match was almost abandoned. Pedestrians occasionally announced a match but were usually greeted with scepticism by the sporting press. For example, Sutton, ‘the Kentish Pedestrian,’ was said to have walked 1,200 miles in 1,200 hours at Brighton in 1827. The Morning Post, was not entirely convinced.[21] Authenticating a Barclay Match, or indeed any multi-day event, is difficult and expensive. Bell’s Life refused for many years to give them any credence. In 1839, for example, their correspondent visited the Stag Tavern on the Fulham Road, where Harris was said to be walking 1,500 miles in 1,000 hours. Bell’s correspondent found him walking in front of ‘half a dozen persons…not one of whom, from personal appearance, could be denominated as ‘respectable,’‘ smoking a clay pipe and looking groggy as if he had been boozing all night.[22] The Era said in 1851 that ‘infamous attempts…have been made for years past to gull the admirers of sport’ with spurious Barclay Matches.[23] Indeed many must be regarded as dubious. For example, Cootes was reported by the local press to have done the half Barclay at a pleasure garden in Norwich in July 1841, but Bell’s Life dismissed it as ‘moonshine.’[24] The same year Henry Raven (the Norfolk Pedestrian) was reported to have done a Barclay Match at the Lord Nelson pub in Lakenham.[25] Whilst strictly speaking it does not speak to the genuineness of the match, it throws some doubts on his bona fides that he was convicted of pig-stealing in 1843 and sentenced to transportation for ten years.[26]

There were proven accounts of fraud and skulduggery. In November 1850, for example, a case in the Birkenhead County Court, reported by the Liverpool Mercury, threw some light on the murky corners. Mitchell, ‘a professed pedestrian,’ sued Homer Holden for £12 2s 10d damages for breach of contract. Mitchell and Holden had got up an event whereby Mitchell would walk half miles in half hours for four weeks, allegedly for a wager of £300. The agreement was that Holden would collect admission money and the two would split it fifty-fifty after deducting expenses. In three weeks they had collected £24 5s 8d in gate money (assuming 2d a time admission, they had already attracted more than 2,900 spectators) when the scam unravelled. Mitchell, it transpired, had been employing ‘ringers’ to walk for him during the night. He might have got away with this, but he made the fatal error of getting drunk and not turning out to walk during daylight. Holden evicted him and kept the gate receipts to defray his expenses. The Court dismissed Mitchell’s claim and described the whole transaction as ‘a blackguard affair from beginning to end.’ [27]

In 1852 a London pedestrian, Bland, announced that he was engaged on the 1,000 half miles in 1,000 half hours at the Porto Bello pub in Henwick, just across the river from Worcester. After some days the landlord’s suspicions were aroused and he visited in the middle of the night to find the pedestrian and his accomplice fast asleep. By daylight they had disappeared, adding insult to injury by absconding with the teapot which the landlord had lent them.[28]

The Era was more sympathetic and was prepared to grant approval to what it regarded as genuine matches; and during the boom of 1851-52 Bell’s relented and began to report several matches as genuine.

James Searles

On 2 October 1843 James Searles began a Barclay Match in Leeds, walking back and forth between the Shakespeare Inn on Meadow Lane and the New Peacock Inn in Holbeck, a distance of one mile and 63 yards. Despite some seasonal bad weather (three or four inches of snow in his second week) he completed the match at midnight on Sunday 12 November. Doubts had been expressed as to the authenticity of the event. Half-way through, the Era was telling the citizens of Leeds not to accept things at face value – that events like this were often merely a scam to collect money from the gullible. But Searles’s connections replied indignantly. A local doctor and a surgeon averred that they were his advisors, he was watched by two people night and day and that ‘large numbers of people assembled to witness his arrival and departure from the Shakspere Inn‘.[29] He finished ‘in the presence of a large concourse of people’ and that evening he was ‘chaired’ in an open coach with five or six of his committee ‘through the principal streets of the town, preceded by the celebrated brass band of Messrs. Maclean and March,’ an engineering firm on Dewsbury Road a short distance from where he started and followed by thousands of admiring spectators’.[30]

Searles’ methods already had an old-fashioned look. By this period most Barclayists had deserted the turnpike roads for enclosed grounds or pleasure gardens. But his performance provoked an outbreak of long-distance pedestrianism on the roads in and around Leeds. In the next few weeks at least three previously unknown pedestrians were reported to be walking Barclay Matches. The sporting press were sceptical, [31] but the local press were easier to convince and it is possible that the 40-year old Mrs Harrison, who walked from the Dragon Inn at Wortley in south Leeds, genuinely completed the distance, thus becoming the first female Barclayist of whom we have any record.[32]

Figure 1. James Searle

The financial arrangements behind Searles’s match are impossible to determine. If a Barclay Match was properly conducted the expenses were high; the cost of handlers, watchers and timekeepers and their accommodation for six weeks, and the training and accommodation expenses of the pedestrian himself made it necessary that there should be a substantial sum guaranteed, or in prospect. Traditionally this came from an initial wager. The pedestrian (or, more likely, his backers) put up a stake against the backers of time. Searles himself claimed that he won a stake of £100, and there were reports in the press at the time to this effect.[33] However, it was the convention then and later or a pedestrian to say that any Barclay Match was for a wager. This was patently not always true. As early as 1816, the Morning Chronicle had said ‘the object of these matches is to bring a crowd daily to some public house, by the landlord of which the pedestrian is engaged.’[34] After pedestrians had retired into grounds established by entrepreneurial publicans, this connection became obvious. There is ample evidence that many itinerant pedestrians who could not secure a backer or the support of a publican still operated on the ‘voluntary system, ‘ where a pedestrian who could find no backers would simply announce that he was walking and would hope for donations from spectators or well-wishers. It sometimes worked, but was obviously very speculative. In addition, the possibility of fraud was high – if there was no one with a large sum bet against the pedestrian there was limited incentive to watch for short cuts or sharp practice.

It is unlikely that Searles would have embarked on such a speculative basis. He was a shrewd operator who already had wide experience of professional sport. He was born in Horncastle in Lincolnshire in 1819. The family moved to Leeds and by the time of the 1841 census were living in the mill district of Holbeck. The local press were unanimous that he had had a tough upbringing. The Leeds Times said that he had been ‘inured to hardship and fatigue during the whole course of his life’. The Leeds Intelligencer, more colourfully, said that his ‘bringing, or dragging, up has been of a description little superior to the caffres of the back regions of the Cape of Good Hope, rarely experiencing the comforts of a bed, and familiar in other respects with every hardship the human frame is capable of enduring.’[35]

His early career is obscure, but when he was first noticed in the sporting press he was already deeply involved in the overlapping circles of pedestrianism and prize-fighting. There is no firm evidence that he appeared in the prize ring, but it seems possible for in August 1843 he was taking a benefit in a sporting pub in Liverpool and issuing a challenge to Cliff of Huddersfield to fight for the substantial sum of £20 a side. In the same challenge he offered to walk backwards against any man in Lancashire or Yorkshire for the same money.[36] James’ younger brother William was a prizefighter, between 1841 and 1847, when his last contest was a fighting defeat by the highly-rated Dick Cain of Leicester in a monstrous 105 round battle at Lindrick Common in Nottinghamshire.[37] After that, he retired to running a sporting pub and sparring rooms in Leeds, where he also offered private boxing lessons.[38] The Searles brothers also kept dogs for ratting and James won substantial sums throughout his career as, for example, in 1849 at Liverpool when his famous dog, Jenny Lind, won a £10 match to kill 100 rats.[39]

However, James chose pedestrianism as his best chance of success. Less than six months later after his first Barclay Match, Searles walked another, in April 1844. This time he left the road and again walked in a garden at the back of the Rising Sun pub in Sheffield. The match is only briefly reported, but it seems to have attracted ‘hundreds of both sexes.’[40] It is therefore surprising that for his third Barclay Match, in August of the same year, he made a serious tactical error. He returned to the open road and agreed to walk between two pubs, the Leopard and the Wheat Sheaf on the Derby Road in Nottingham. He started on a Monday afternoon, ‘large crowds of people constantly lin[ed] the path the whole of the way’ but at half past ten the following morning the county police moved in and put a stop to the whole enterprise. [41]

Searles reverted to the lifestyle of a top-flight pedestrian. He ran ten miles against Thomas Birkhead (alias ‘Lammas’) of Sheffield at the Hyde Park Ground; ran five miles jumping 52 hurdles against time on Nottingham Race Course; ran ten miles and jumped 100 hurdles against time at Vauxhall Gardens, Birmingham; ran twenty miles and jumped 150 hurdles, again against time at Vauxhall Gardens; picked up 300 stones against Thomas Hick of Leeds (each stone being one yard further away than the last and all to be brought back to the start individually – an overall total of 51 miles 540 yards); ran four miles and jumped 200 hurdles at Birmingham against time; and ran eighteen miles against Birkhead at Hyde Park.[42]

In December 1845, he got his own beerhouse in Leeds, inevitably renamed the Pedestrian Tavern. From here, he promoted races, and for a time continued to run (he won a four-mile hurdle race on Holbeck Moor near Leeds in February). Almost incredibly, he also contemplated returning to the prize ring – in February 1846 he exchanged challenges with Edward (‘Chatty’) Edwards to fight for twenty-five sovereigns, though like many challenges it came to nothing.[43] At Manchester Races in Whit week 1846 he ran in a handicap hurdle race and came second.[44] However, between then and 1850 he appeared only once in a running contest. In February 1847, he raced John Rhodes of Wolverhampton over 8 miles at the Hyde Park Ground in Sheffield for a stake of £15 a side. There was considerable interest amongst the betting fraternity and a lot of money had been wagered, the ‘smart money’ being on Searles, who won by three yards.[45] At the beginning of 1848, he gave over the Pedestrian Tavern to his brother William. In April of that year, it was reported that he had ‘been in the hospital for some weeks.’[46]

Barclay Matches in 1850

Searles made his comeback in April 1850, at the age of thirty, to win a half-mile hurdle race at the Cemetery Tavern Cricket Ground, Hunslet, in Leeds.[47] In July, he ran eight miles against Mickey Free[48] of Liverpool on Aintree Racecourse. The stakes were £15 a side and both had to run in clogs. Searles was narrowly beaten by two yards in a time of 70 minutes.[49] He was eager to get back into long-distance pedestrianism, but, even as he was running in Liverpool, the revival of the Barclay Match had begun in Sheffield.

By 1850, there were several well-established pedestrian grounds in the north. Edward Broadbent, the proprietor of a minor Sheffield ground, the Barrack Tavern Cricket, Bowling and Pedestrian Ground, had started holding races there in 1848 and was trying to build up his pedestrian business in the shadow of the great Hyde Park Ground.

He decided that a Barclay Match would be an attraction and selected as his pedestrian Richard Manks. Manks (the Warwickshire Antelope) one of the best middle and long-distance runners of the age, was born near Solihull in 1820.[50] He had been running since 1843. He had been backed by Broadbent since at least 1847, when Broadbent had put up the £100 at stake for Manks’s run against Jackson in one of the great ten mile matches of the era.[51] Manks, like Searles, kept a beerhouse, the Pedestrian’s Retreat, in Sheffield.[52] He had no previous Barclay experience, but was a versatile and experienced athlete possessed of immense endurance – he said that in his earlier years he worked as a brickmaker and that the physical labour and long periods of wakefulness stood him in good stead in his later ultradistance feats.[53] He started on 17 June, survived major foot problems (surgeons had to scarify his feet) and he got through the 42 days.

On the day before he reached his 1,000 miles (Sunday 29 July) excitement was tremendous, ‘crowds upon crowds flocking every hour to the ground.’ It was reported that 15,000 to 20,000 were there during the day and evening. The same on Monday morning, when he finished at eight o’clock in the morning. Broadbent gave him the gate money from Sunday and Monday, collections were made for him at public houses in Sheffield and it was estimated that Manks made the immense sum of £200 from the match.[54]

Searles responded by organizing his own Barclay match. It was reported that he had staked £100 to £150 which was bet against him doing the distance.[55] He made a deal with Mrs Fernyhough of the Tranmere Hotel in Birkenhead to host the match. A 440-yard track was levelled and cindered in the field by the hotel, looking across the Mersey to Liverpool. He started on Monday 2 September. Admission to the ground was 2d. In the first week, the Liverpool Mercury reported, the public houses in Cheshire and the ferries across the Mersey were already benefitting from the hundreds who had already crossed to witness the event.[56] Total gate receipts by the end were £211 12s 7d, which indicates over 25,000 paying spectators over the course of the six weeks.[57] He was due to complete the 1,000 miles at 7 a.m. on Monday 14 October. A ‘vast number’ had arrived by steamer to witness the end. Just before starting the last mile, a gentlemen unwisely offered Searles a bet of £10 that he would not walk it in under 8 minutes. Searles started immediately after 7 o’clock and completed his mile in the ‘extraordinary short space of 7 minutes 41 seconds’. He then ran a lap of honour, ‘amid the cheering of the multitude.’ He milked the event for all it was worth. He put on a day’s performance for the crowds who continued to flock in (the unofficial ‘St. Monday’ holiday was obviously still honoured in Liverpool at this time). He continued to walk a mile every hour until four in the afternoon; four of those miles he walked backwards, in under fifteen minutes each. He finished by running a lap, outsprinting his pugilist brother, William, and was carried round the course by supporters to the strains of the resident band.[58]

1851

The 1851 Barclay season began on Monday evening 23 June at the Cricket Ground on Halifax Road in Huddersfield when Luke Furness of Sheffield began to walk a standard Barclay Match. Furness (‘the Park Stag’) was an experienced pedestrian who had been competing in Sheffield since at least 1846.[59] By the fourth week it was becoming difficult to rouse him for his night time hours and ‘some of the miles at these periods were walked in a state of unconsciousness.’ When he was going through a particularly bad patch his minders resorted to the ruthless method of firing a gun by his ear.[60] He had a great number of visitors especially on Saturdays and Sundays and he finished at noon on 4 August.[61]

However, the year was to see major developments in the Barclay Match and again they were initiated by Manks and Broadbent. On the same Monday evening that Furness began his match in Huddersfield, Manks at the Barrack Tavern Ground began the most gruelling variation of the Barclay Match yet devised. He would walk 1,000 quarter miles in 1,000 consecutive quarter hours (i.e. 250 miles in 10 days and 10 hours), then immediately 1,000 half miles in 1,000 consecutive half hours (i.e. 500 miles in 20 days and 20 hours), followed immediately by a conventional Barclay Match (1,000 miles in 1,000 consecutive hours). This would amount in all to the monumental total of 1,750 miles in 72 days and 22 hours. As if this were not enough, he would begin walking his quarter miles at the beginning of each quarter hour, the half miles on the half hour and the miles on the hour.[62]

Manks and Broadbent were taking the risk that interest could be sustained for more than ten weeks, but in the event they succeeded brilliantly. The Era and Bell’s Life were dubious at first, but soon accepted it as a genuine and honest event and the spectators poured in, reportedly up to 10,000 spectators a week in August.

Searles had again been upstaged by Manks. On 7 July, two weeks after Manks began his Sheffield epic, Searles started a standard Barclay Match in London. His sponsor was James Ireland, the proprietor of the Red House at Battersea. The Red House, situated on the river, beside the present Albert Suspension Bridge, had been a pub, pleasure gardens and place of resort since the eighteenth century. Famously, it had a large pigeon-shooting ground, formerly patronized by the aristocracy, but by the 1840s had gone down in the world. It had just been compulsorily purchased to allow the construction of Battersea Park; Ireland seems to have been determined to make what profit he could in the remaining time. The press were unanimous that this was a genuine match. Ireland provided timekeepers and a policeman at the ground, which was kept open all night, ‘vast numbers at different times ha[d] paid a nocturnal visit, and a £20 reward was offered to anyone who detected any fraud in the proceedings. It was ‘a remarkable fact,’ said Reynolds News, ‘that, whether from curiosity or interest, Searles never was without watchers … owlish late at night or early in the morning visitors, who noted his times of rest and of starting.’[63]

By the middle of August Manks had passed 1,300 miles at Sheffield. Betting was heavy not only in Sheffield but also in Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds.[64] The numbers attracted to the Barrack Ground were astonishing, even allowing for the vagaries of newspaper estimates. On Monday 18 August, reported the Era, from noon to 9 p.m. there had been at least 10,000 visitors, many coming by special trains from Leicester, Nottingham, Leeds, Bradford, Derby, Manchester, Birmingham and other towns within a sixty mile radius; the total for the week was probably more than 20,000.

On the same day at Battersea Searles completed his 1,000 miles, Ireland celebrated; there was free food for everyone there to witness the finish – a roast ox, a 112 lb. plum pudding, a monster 40 cubic foot loaf and a butt of the aptly named Barclay’s beer.[65] But Searles and Ireland were aware of the ever-increasing publicity given to Manks’s Sheffield walk. At some point in early August they had agreed that Searles would continue and try to equal Manks’s total. If he succeeded, Ireland would add £50 to the £100 he was already promised.[66]

In Sheffield no opportunity for publicity was lost. Bendigo, the ex-champion and most famous prize fighter of the day, was enlisted as an added attraction for the final two weeks.[67] James Ireland came up to Sheffield for Manks’s finish on 4 September. Broadbent returned the compliment by going to Battersea to see Searles finish on 18 September.

Despite the success of both events, the experiment of having a duration of more than six weeks was never repeated. All future variants of the Barclay Match kept to the 1,000 hour time limit, although it became almost the norm to go beyond the 1,000 mile distance.

The pedestrians continued to try to cash in on their notoriety. Only three weeks after finishing his epic walk at Sheffield Manks was back on the track for another challenge. He moved south to the Kennington Oval Cricket Ground to repeat perhaps the most gruelling portion of the Sheffield performance, the 1,000 miles in 1,000 half hours, beginning at 6 p.m. on Friday 26 September. He seems to have gauged well that he could attract crowds in London on the interest created by his Sheffield match. Even the normally snooty Bell’s Life condescended to take notice; they reported in detail and even appointed the watchers. All went well until Monday morning, when he was suddenly and violently attacked by diarrhoea. On medical advice he gave up the attempt, when he had gone 129 miles.[68] But he was not going to allow this to break the momentum of this great sporting year or waste any money-making opportunity. Searles was still in London and after Manks had recovered for a couple of days an event was cooked up ‘on the spur of the moment,’ a ten mile hurdle race between the two at Kennington Oval on Monday 6 October at stakes of £15 a side. Searles ceded to Manks by stepping off the track at seven miles. Afterwards, the word was that he was out of condition because of ‘fast’ living since finishing his Battersea epic.[69] Manks persuaded the Kennington Oval proprietor to allow him to recommence his aborted ‘fast’ Barclay match on the afternoon of Friday 10 October. Interest in the event was muted. The proprietor employed a designer to illuminate the Oval at night with 1,000 ornamental lamps and seems to have had some success. On the last day (Friday 31 October) he attracted a crowd estimated at 5,000.[70]

Challenge and counter-challenge continued between Manks and Searles, until unexpectedly Searles announced that he was retiring, for the second time, to become the landlord of a public house and that he would be accepting no more challenges. On Monday 10 November he returned to the Red House and performed his final match, jumping 1,000 hurdles against the clock and by the beginning of December he had moved into the Brickmakers’ Arms in Brook Street North, in Birkenhead, which he renamed the Champion’s Rest Tavern But his withdrawal from active participation in athletics lasted barely three months. He emerged from retirement in April, when he was backed by a Liverpool ‘sporting gentleman’ to walk ‘fair heel and toe’ two miles in 14 minutes 30 seconds. Bell’s Life was of the opinion that it could not be done. The match came off on a mile of turnpike road near Birkenhead, where 8,000 spectators saw him finish in 14 minutes 25 seconds. There was some scepticism about the performance, but Searles issued a challenge to any metropolitan doubters that he would repeat the same performance in London.[71]

1852

In 1852, the fashion to walk longer or faster variants of the Barclay Match reached its peak. That year there were, up and down the country, at least eleven matches, only one of which Captain Barclay would have recognized as respecting his classic time and distance.

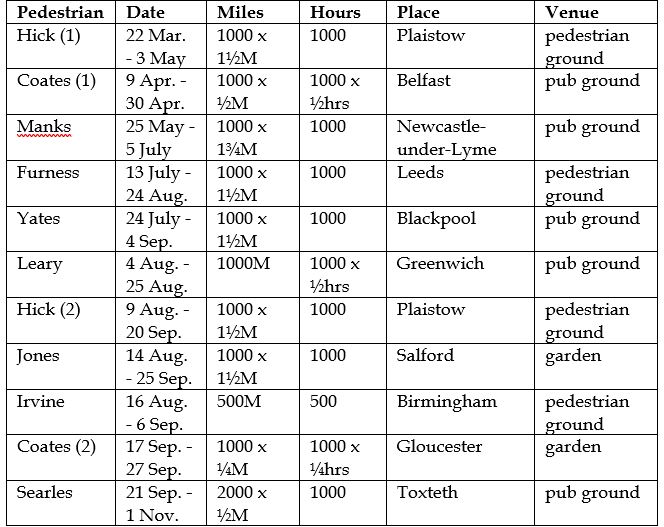

Table 1. Barclay Matches and variants in 1852

Thomas Hick

The year opened with another running ground entrepreneur seeking to use a Barclay Match to publicize his venue. In November 1851, William Beswick had opened a new running ground at the Royal Oak, Plaistow, close to the new Barking Road Station on the Eastern Counties Railway. He announced a 1,500 mile Barclay Match, with Thomas Hick of Leeds, for what was said to be a stake of £50. Hick had no reputation in London, but was no mean performer. He had beaten Searles in a 51 mile match to pick up 300 stones in 1845 and had put up a good fight against Manks in another 300 stone match.

Hick started on Monday 22 March. The usual doubts were expressed as to whether this was another gate money scam, but Bell’s Life were convinced by Beswick’s protestations of probity and in fact the paper appointed two watchers.[72] With a surprising lack of foresight, his last mile and a half was scheduled for three o’clock on a Monday morning (3 May), but Beswick turned it to his advantage. On the Sunday 4,000 spectators visited the ground. It was reported that between five and eight o’clock on Sunday night ‘great alarm was created’ as ‘Hicks was showing great distress and requiring unremitting attention from his attendants’. Whatever the nature of the ‘attentions’ he received, he recovered and large numbers stayed on the ground until he finished, at twenty-two minutes past three in the morning. A bonfire was lit and the last mile and a half was walked in procession with lighted torches and a band.[73]

Robert Cootes

In April 1852 the evergreen Cootes was in Ireland. A ‘party of sporting gentlemen’ had subscribed a purse of 60 sovereigns to bring him to Belfast to walk a half Barclay Match (1,000 half miles in 1,000 half hours). The event was accommodated at the Thatched House Tavern sporting ground in Frederick Street, on a 110-yard circuit. He started on Good Friday (9 April) and completed on the 30th, apparently much peeved that only a few spectators had turned out to see him finish.[74] Astonishingly, six days later he appeared in Bristol and began another event of 1,000 half miles at the Zoological Gardens, apparently with the guarantee of £50 if he finished. He began on Thursday evening but on the Saturday morning the Bristol Mercury published a tirade against the zoo having permitted such a vulgar and ‘brutalising exhibition’ in Clifton. The committee caught the general feeling and by that afternoon had paid off Cootes with £20 compensation. The attempt ended barely forty-eight hours after it had begun. [75] Later in the year he dashed off a ‘sprint’ Barclay Match, 1,000 quarter miles in 10 days, at the Vauxhall Gardens in Gloucester, finishing on Monday 27 September.[76]

Manks

On 25 May, Manks began to walk 1,750 miles in 1,000 consecutive hours at the bowling green at the Noah’s Ark, Hartshill near Newcastle under Lyme in the Potteries. As the clock struck the hour, he set off to walk one mile; at the half hour he walked half a mile, which he had to complete within 15 minutes because at the stroke of three-quarters of an hour he walked a quarter of a mile. The weather was foul, the circuit was muddy, he had blisters and knee trouble and he became so overwhelmed with sleep that (unspecified) stimulants had to be administered. There was very little reporting of the event, and Bell’s only mentioned it once, and then with a hint of doubt in their brief report. The Era, however, reported that he finished, on 5 July, in good health and with his usual ‘robust appearance’ when a ‘very respectable bevy’ turned out to see him.[77]

Luke Furness

In June 1852 the first pedestrian ground in Leeds was opened by William Cowburn alongside his Airdale Tavern on Hunslet Lane. In an attempt to establish the venue, he packed the summer months with attention-seeking events and adopted the now almost common ploy of putting on a Barclay Match. He invited Luke Furness of Sheffield to do 1,500 miles in 1,000 hours, in July and August.[78] Furness finished his 1,000 miles at four o’clock on Tuesday morning 24 August, but despite his best efforts the Airdale Ground was not a success and closed by the end of the year.[79]

James Yates

The Huddersfield Chronicle reported that on 25 May James Yates of Worcester had begun to walk 1,500 miles in 1,000 hours on a staked-out circuit of a field in Halifax.[80] However, after this single report no further news can be traced and we have to assume that he never completed. Yates unfortunately has form in this area – we know that he gave up in a match later that year.

On Saturday 24 July, however, he appeared at Blackpool (at Sutcliffe’s No.3 Inn and Pedestrian Ground) and began to walk 1,500 miles in 1,000 hours, commencing with the first quarter of each hour. By the half-way mark he was reported to be still going strongly despite a week of heavy August rains. His advertisement in Bell’s said that railway excursions had come from ‘all the principal towns in Lancashire and Yorkshire to the beautiful sea bathing town’ and that up to 30,000 spectators had visited. (The railway station was half a mile from the ground.) The press did confirm that he had thousands of spectators, including the ‘most respectable.’[81] He finished on 4 September. Because of the financial success Yates continued for another five days, this time walking 500 quarter miles every quarter of an hour (i.e. 5 days 5 hours).[82]

Later in the year he was involved in two abortive Barclay Matches. On Saturday 25 September he began to walk a ‘double Barclay’ of 2,000 miles at Trent Bridge Cricket Ground but was forced to abandon after two weeks, apparently because of Sabbatarian objections.[83] He then started a 2,000 mile, 1,000 hour walk, on Wednesday 3 November, at the Hippodrome, Kensington. Watchers were employed and Yates walked for a week. However, early on the morning of Wednesday the 10th, Yates and his attendant decamped by the back door, leaving everyone unpaid. Bell’s opined that the watchers had been good and Yates had realized that he was not going to be able to keep up the pace.[84]

Thomas Hick

At 10 o’clock on Monday night 9 August the indefatigable Thomas Hick of Leeds returned to the Royal Oak in Plaistow and completed his second 1,500 miler of the year.[85]

James Jones

On Saturday 14 August at the Borough Gardens, Salford, James Jones from London, aged about 25 and, as far as we know, a novice in long-distance events, began an attempt on 1,500 miles in 1,000 hours.[86] He walked on a 377 yard track through the garden (i.e. seven circuits per one and a half miles). The usual suspicions were voiced that Jones might have used a substitute walker at night, but The Era and the Manchester Guardian said that they thought the match was genuine.[87] Attendance was said to be ‘hundreds…day and night’; his team claimed 4,000 spectators in the first two weeks, 3,000 on the first Sunday in September, and attendance was especially good in the last two weeks of the event and it was evidently a financial success for all concerned.[88] Admission to the ground was 2d and the proprietor was able to give Jones £100 from the proceeds. He completed on the morning of Saturday 25 September.[89]

Kate Irvine

As Jones was starting his walk in Salford, ‘huge placards’ appeared in Birmingham announcing that the American pedestrienne Kate Irvine was about to attempt a half Barclay Match (500 miles, 500 hours) at the Aston Cross Ground in Birmingham. Having decided to go for a full Barclay Match instead, she duly began on 16 August – This was now the sixth Barclay Match of the summer, five of them taking place simultaneously. She attracted good audiences and finished on 6 September.[90]

Searles

Searles soon announced that he had sorted out the finances, would be walking in late September and would walk 2,000 miles in 2,000 consecutive half hours, the longest Barclay Match ever. Obviously, he would have barely fifteen minutes rest each half hour before he had to walk another mile. He would again walk in Liverpool. He walked on an enclosure behind the Pine Apple Inn, Park Road, Toxteth, ‘on an eminence which commands a view of the town on one side, and of the Mersey and Cheshire shore on the other.’[91] The circuit was one seventh of a mile; it was marked out with ropes, with boards laid down for a better footing during the wet weather. He started on Monday evening 20 September. The event looked like being a commercial success – ‘large number[s]…many from a distance, have already been attracted to the grounds.’ Soon upwards of 14,000 had been to see him.[92] Large bets on the race were being made; Searles himself was heavily involved, he was offering all comers two to one that he would complete.

On Sunday 24 October, 2,000 were said to have come to see him. According to the Era, the police ‘watched the pedestrian pretty closely’ in case there was ‘a dodge in the affair’.[93] He was to complete the 2,000 miles at 10 o’clock in the morning on Monday 1 November. On Sunday a band played all day and 3,000 spectators were there in the afternoon. Large bets had been placed on how fast he would walk the last mile. Beforehand, he was so little fatigued that he was able to put on his own shoes and tie them. He duly gave a crowd-pleasing performance. He started at seven minutes a mile pace. His brother William, tavern keeper and ex-prize fighter, kept up with him for half a mile then dropped out exhausted and James went on to finish in seven and a half minutes. [94] On Tuesday evening he had a benefit at the Adelphi Theatre. Between the performances of ‘Dick Turpin’s Ride to York’ and ‘Guy Fawkes,’ he appeared in his walking strip and champion’s belt and danced a hornpipe in clogs, in front of a full house, to tumultuous applause.[95]

Barclay Matches continued sporadically for a few years after the boom years of 1850 to 1852. But the bubble had burst. A genuine Barclay Match involved a considerable financial outlay over six weeks and promoters were not coming forward. Spectator interest was waning, no doubt hastened by the number of fraudulent events. Professional pedestrians, and equally importantly, professional backers were turning their attention to the sprint challenges and handicaps and short and middle distance races in the rapidly multiplying pedestrian grounds of the 1850s and 1860s.

The greatest exponents of the Barclay Match were coming to the ends of their careers. After his great walk at Toxteth, James Searles retired to the licensed trade, moving to the Beehive in Cross Hall Street in Liverpool (of course renamed the Champion’s Rest). We know of only one more race that he ran. In 1854 he spent time in America; in September of that year he walked a seven mile race against local man Boyd, the ‘North Star,’ for stakes of $1,000. Searles was heavily backed to win and in fact finished fifteen yards ahead of the American. But the judges disqualified him and awarded the race to Boyd.[96] Back home he continued to be involved in the training or backing of pedestrians.[97] However, he was more deeply involved in ratting events – ‘Ratting every Tuesday night [at the Beehive]. A good supply of rats on hand,’ as he proclaimed in Bell’s Life. Searles’ dog, Jenny Lind, was a famous canine phenomenon of the time – she killed the astonishing total of 500 rats in 96 minutes at the Beehive in 1853.[98] After 1858 he disappears from the record. He died in Liverpool in 1866.

Richard Manks continued as an active pedestrian for ten years after his last Barclay Match. In 1862 he was in Leeds, at St Thomas’s Ground, Stanningley. Now forty-one years old, he took on a match for £25 a side against Laycock to walk fifteen miles, throwing 200 56lb weights over his head during the course of the match – he lost narrowly.[99] In December 1862 he walked 56 miles a day, for six consecutive days, between Maidstone and Tunbridge and then seems to have retired from athletics.[100] Manks died in February 1869, in Sheffield, where a ‘great concourse of spectators’ lined the streets at his funeral.[101]

There were occasional Barclay Matches over the next fifty years. A few specialists created more and more difficult variants, the most notable being William Gale, who in 1877 at the Agricultural Hall, Islington, walked 4,000 quarter miles in 4,000 successive quarter hours.[102] But this was a niche interest – multi-day professional events did not become a popular money-making propositions again until a new format was invented twenty years later. The inheritance of Captain Barclay passed to the professional indoor six day racers of the later 1870s, introduced by the American Edward Payson Weston and promoted, in Britain and America, by Sir John Astley.[103]

References

[1] Walter Thom, Pedestrianism (Aberdeen, 1813); Peter Radford, The Celebrated Captain Barclay (London, 2001).

[2] Josiah Eaton, A Sketch of the life of the Author (1839), 9. Eaton published his apologia in Quebec, to where he has emigrated in 1829. Disappointingly, he disposes of his pedestrian feats in two paragraphs and devotes the remainder of his memoir to explaining how he found himself in prison for debt several times (by guaranteeing the debts of various improvident or deceitful friends or business acquaintances who took advantage of his good nature). His claim that he did not walk for gain is arguably not consistent with reports of the large wagers involved in many of his walks.

[3] Morning Post, December 27, 1815.

[4] Bell’s Weekly Messenger, July 21, 1816.

[5] York Herald, October 19, 1816. The stakes were variously reported as £500 a side or £1,500.

[6] Morning Chronicle, October 25, 1816; Northampton Mercury, December 21, 1816.

[7] Morning Post, May 26, July 6, 1818.

[8] He was born in 1747 and was a silk weaver by trade (Morning Post, September 26, 1816).

[9] Courier, July 13, 1816; Morning Post, July 16, July 29, 1816; Cambridge Chronicle, August 9, 1816; Ipswich Journal, August 10, 1816.

[10] He was born near Pocklington in East Yorkshire (Morning Post, November 6, 1821).

[11] Morning Chronicle, May 20, 1819.

[12] Courier, April 20, 1822; Sporting Magazine, vol. 10 (N.S.) (May 1822), 103.

[13] Bell’s Life, July 3, 1842.

[14] Bury and Norwich Post, July 24, 1816; August 1, 1827.

[15] Hereford Journal, September 3, 1823.

[16] Bath Chronicle, June 20, 1822

[17] Again at Newmarket (Sporting Magazine, vol. 11 (N.S.), (October 1822), 50

[18] There are conflicting accounts of whether or not he succeeded: cf. Weekly Free Press, August 4, 1828; Era, July 29, 1849.

[19] New Times, April 12, 1828; Standard, May 24, 1828.

[20] Era, July 29, 1849.

[21] Morning Post, November 8, December 29, 1827.

[22] Bell’s Life, May 6, 1839.

[23] Era, October 26, 1851.

[24] Bell’s Life, January 2, 1842.

[25] Norfolk Chronicle, November 13, 1841.

[26] Norfolk Chronicle, January 7, 1843.

[27] Liverpool Mercury, November 29, 1850.

[28] Worcester Chronicle, October 6, 1852.

[29] Leeds Times, November 11, 1843; Leeds Intelligencer, November 18, 1843.

[30] Era, October 22, 29, November 12, 1843; Leeds Intelligencer, November 18, 1843.

[31] Era, December 10, 1843.

[32] Leeds Intelligencer, January 6, 1844; Era, January 28, 1844.

[33] Leeds Intelligencer, October 7, 1843.

[34] Morning Chronicle, October 25, 1816.

[35] Leeds Intelligencer, November 11, 1843.

[36] Era, August 27, September 10, 1843. The challenges were issued in the name of ‘James Tigser of Leeds.’ Tigser was an alias used by Searles and his brother in their early days.

[37] Bell’s Life, August 1, 1847.

[38] Bell’s Life, October 12, 1851.

[39] Era, October 21, 1849.

[40] Sheffield Independent, August 24. 1844. Bell’s Life, as usual, was suspicious but did not go as far as to say that it was a scam (Bell’s Life, April 28, 1844).

[41] Sheffield Independent, August 24, 1844.

[42] Bell’s Life, July 21, 1844; Era, September 8, 1844; Bell’s Life, October 6, 1844; Era, October 27, 1844; February 9, 1845, Bell’s Life, November 30, 1845.

[43] Era, February 22, 1846.

[44] Manchester Courier, June 3, 1846.

[45] Era, March 14, 1847.

[46] Bell’s Life, April 30, 1848.

[47] Era, April 28, 1850.

[48] Mickey Free was the alias of Robert Harriott, described by Bell’s Life as ‘bold and eccentric’ (Bell’s Life, October 5, 1851), later to be a Barclayist and a convicted felon – see below.

[49] Bell’s Life, July 7, 1850; Era, July 7, 21, 1850.

[50] Born 3 May, Bell’s Life, February 14, 1847; Yorkshire Gazette, August 3, 1850; Leeds Times, June 28, 1851 (but quaere Sheffield Daily Telegraph, March 3, 1869).

[51] Bell’s Life, February 14, 1847.

[52] Era, December 30, 1849.

[53] Preston Guardian, August 23, 1851.

[54] Era, August 4, 1850; The Times, August 12, 1850.

[55] Liverpool Mercury, September 6, 1850.

[56] Liverpool Mercury, September 6, 1850; Era, October 13, 1850; Lloyds Weekly Newspaper, September 15, 1850.

[57] An old opponent of Searles,…, was attempting to walk 1,100 miles in 1,100 hours at the Strawberry Gardens, Everton (Era, October 13, 1850). The extra mileage, however, was his undoing. Having passed the Barclay 1,000 miles he walked for just ten more hours then surrendered from exhaustion at 1,010 miles.

[58] Liverpool Mercury, October 15, 1850; The Times, October 17, 1850. Unfortunately, financially it all ended in tears. Fernyhough sued Searles for £60 in a dispute over expenses (Era, November 10, 1850) – we do not know the outcome of the case.

[59] He was aged 36 or 37 at this time (Era, July 18, 1852).

[60] Huddersfield Chronicle, July 26, 1851. The use of firearms in Barclay Matches is well attested. When Mickey Free walked 1,010 miles at Everton in 1850, his handler had used a pistol to wake him up during the night. Unfortunately, Mickey was still carrying the pistol as he was celebrating the end of the match in the Jamaica Vaults in Hopwood Street in Liverpool when he had an altercation with his wife. Conceiving the idea that she was attacking him, he shot her, hitting her in the hand and amputating two fingers. He received a comparatively lenient sentence of nine months imprisonment (Manchester Times, December 18, 1850).

[61] Liverpool Mercury, October 15, 1850.

[62] Era, June 29, 1851.

[63] Reynolds News, August 24, 1851.

[64] Era, August 24, 1851; September 7, 1851.

[65] Era, August 17, 1852.

[66] Era, August 24, 31, 1851.

[67] Era, August 24, 1851; September 7, 1851.

[68] Bell’s Life, October 5, 1851.

[69] Era, October 12, 1851.

[70] Bell’s Life, October 26, 1851; Era, November 2, 1851.

[71] Era, April 11, 18, 1852.

[72] Bell’s Life, March 21, 1852.

[73] Era, May 9, 1852.

[74] Morning Chronicle, April 16, 1852; Belfast Newsletter, May 3, 1852.

[75] Bristol Mercury, May 8, 15, 1852; Gloucester Journal, May 15, 1852.

[76] Gloucester Journal, September 25.

[77] Era, June 13, July 11, 1852; Bell’s Life, June 20, 1852

[78] Era, July 18, 1852; Bell’s Life, August 29, 1852.

[79] Cowburn was declared bankrupt in December 1853 (London, December 23, 1853).

[80] Huddersfield Chronicle, May 29, 1852.

[81] Bell’s Life, August 1, August 15, 1852; Preston Chronicle, September 11, 1852.

[82] Preston Chronicle, September 4, 11, 1852.

[83] Nottinghamshire Guardian, September 30, October 14, 1852.

[84] Bell’s Life, November 7, 14, 1852.

[85] Bell’s Life, September 26, 1852.

[86] Bell’s Life, August 15, 1852. The match was said to be for £100 ‘subscribed by a number of persons in Manchester and Salford’.

[87] Newcastle Guardian, September 18, 1852; Era, October 3, 1852.

[88] Leeds Times, October 2, 1852.

[89] Era, August 29, October 3, 1852; Leeds Mercury, October 2, 1852, Era, October 3, 1852.

[90] Era, August 22, 1852; Bell’s Life, September 5, 1852.

[91] Nottinghamshire Guardian, October 14, 1852.

[92] Liverpool Mercury, September 24, October 8, 1852.

[93] Era, November 7, 1852.

[94] Liverpool Mercury, November 2, 1852.

[95] Liverpool Mercury, November 5, 1852.

[96] New York Times, September 5, 1854.

[97] For example, in 1858 he was prepared to back his novice walker in a 20 mile match to the tune of £25 (Bell’s Life, October 17, 1858).

[98] Bell’s Life, July 24, 1853.

[99] Era, Bell’s Life, January 5, 1862.

[100] Dover Express, December 13,1862.

[101] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, March 4, 1869.

[102] Morning Post, November 19, 1877.

[103] Marshall, P.S., King of the Peds (Milton Keynes, 2008); Harris, N., Harris, H. and Marshall, P., A Man in a Hurry: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Edward Payson Weston, The World’s Greatest Walker (London, 2012).

I presume you have seen James Searle’s Champions belt being restored in the current series of ” The Repair Shop ” …

Chris,

many thanks, I had no idea! Have looked at it on BBC iPlayer – fascinating.

Derek

Hi Derek,

After edited my last edited collection on Match Fixing and Sport I seem to come across manipulation of sporting performances everywhere. It seems to have been almost normalized in pedestrianism doesn’t it?

Indeed, Mike

just been reading an 18C pamphlet – “at Bansted Downs or Hackney Marsh there’s not one horse race in twenty but what’s a cheat … foot-raceing is just the same”.