While Part 1 of this paper [which can be read HERE] used documentary evidence gleaned from official records, newspaper reports and family documents, Part 2, though employing American federal records and newspaper accounts (as well as British records) also involves a certain degree of supposition as the documentation is sketchy or contradictory. To further muddy the waters official certification in the USA did not become common practice, or even mandatory, in some of the States concerned until years after Lizzie’s demise.

A study of the newspaper articles and advertisements that informed the public of the various engagements that Lizzie and Agnes undertook highlight the fact that after the death of their father the sisters joint performances faltered until they stopped performing together completely and appear to have gone their separate ways. Agnes continued to demonstrate her swimming prowess across the country with her own troupe, which now included niece Aggie, daughter of Charles, who was styled “Miss Agnes Beckwith, Junior”, it was suggested that she would follow in her Aunt’s footsteps, keeping the Beckwith name alive in the world of natation. Young Aggie was also the “possessor of a very pleasing voice” and often sang songs, including a ‘delightful’ rendition of the song “Queen of the Earth”, during the troupe’s performances.

- Miss Agnes Beckwith Junior

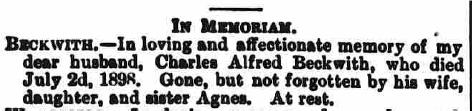

Lizzie likewise, as previously described, carried out ornamental swimming, diving and soubrette engagements across the south of the country, but the sisters never appeared on the same stage together again. While there was never any reports of bad feeling or competition between the two separate Beckwith troupes equally there is no official or family documentation that would suggest that the sisters helped each other out. There is one perhaps small indicator that might point to a family rift of sorts; for several years, the anniversary of the death of brother Charles was marked by a memorial advert, taken out by his widow, in which Agnes was always referred too, but Lizzie (or her brother Bobbie) not.

- The Era – 6th July 1901

Making a living on the entertainment circuit as a single woman with two children to support must have been hard for Lizzie. Her own mother was an inmate at the Marylebone workhouse and therefore unable to offer help and her brother Bobbie, only a teenager, earned very little as a Theatre Clerk at the Empire Theatre in Leicester Square.

- Sketch of Lizzie performing on the swimming circuit – Nottingham Guardian 30th September 1893

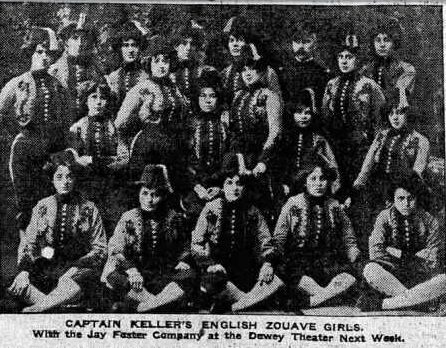

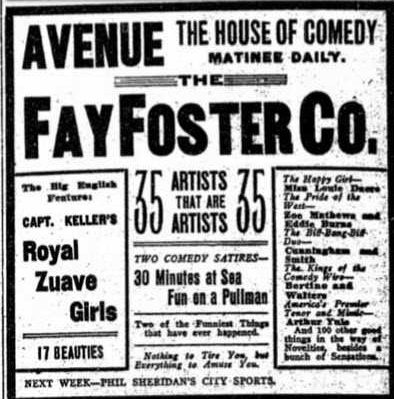

In July of 1904 Lizzie accepts an engagement in America, along with sixteen other female variety artistes from the Alhambra Theatre in London, to form a troupe to be called the Captain Keller’s Royal Zouave Girls. After leaving her children under the care of her landlady with the promise of sending money for their upkeep, she sets sail aboard the SS Umbria, arriving in New York on 28th July 1904, the troupe by all accounts were due back in London the following May. A few days later in the Sporting Life a notice from a Harry Burns, who was once trainer to the ill-fated diver Tommy Burns and latterly an agent/manager on the swimming circuit, was published requesting that Lizzie sends her address immediately. There are many reasons why Burns would wish to contact Lizzie, ranging from money owed to her for public appearances to perhaps a broken contract, however with no other information on this too much speculation is meaningless.

Meanwhile Lizzie and the rest of the Zouave Girls travel around America with a burlesque revue known as The Fay Foster Company, Keller’s group were reported as being;

“most admired and the troupe is admirably drilled and executes intricate

manoeuvres at terrific pace. The highlight of the act is a wall scaling

stunt which is performed with remarkable agility and dispatch.”

- The Minneapolis Journal – 3rd December 1904

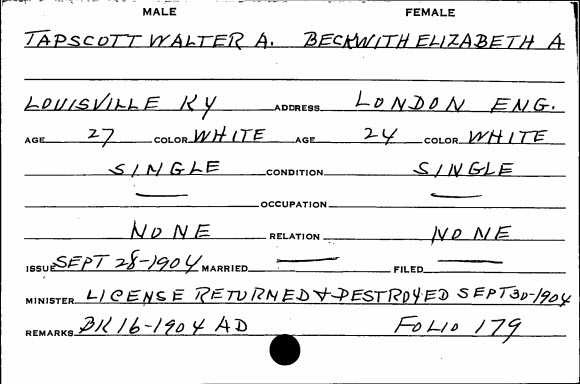

The company tour America, performing as such cities as Detroit, St Louis, Minneapolis, Minnesota, Connecticut, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, Washington DC and Reading, Pennsylvania. While in Reading, family papers claim that Lizzie obtained a divorce from William Woolley, but no documentary evidence for that has surfaced. Further to this, in September 1904 the New York newspaper The Morning Telegraph ran an article headed “May Be Married and… May Be Not….” in which it was reported that two members of the Fay Foster Burlesque Company, playing at the Kernan’s Monumental Theatre, namely Walter A Tapscott and Elizabeth Beckwith, has secured a licence to be married. Tapscott was noted as being a knockabout comedian, known professionally as Fred Walters. It was additionally stated that the couple had refused to say whether the licence had been used and had vigorously expressed their chagrin at the fact that the press had invaded their privacy by publishing the details. It was alleged that the manager of the company, Joe Oppenheimer, had issued a “ukase against love-making in the company” Tapscott and Beckwith being especially cautioned. Oppenheimer further warned the couple that a marriage would be equivalent to a discharge from the company.

- Detroit Free Press 25th December 1904

The copy of the official licence, see below, shows that it was returned and destroyed on 30th September 1904, thus suggesting that the marriage never took place. However, consequent newspaper reports alleged that the couple did in fact marry and were ultimately sacked by Oppenheimer, turning to the vaudeville circuit to make their living, with some success.

- Wedding Licence – Family Papers

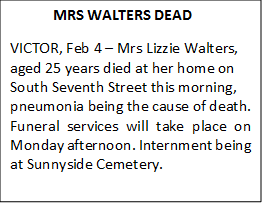

Their marriage, if indeed there was one, was destined to be short lived when on 4th February 1905, at the age of 25, Lizzie died. The story captivated the American press with many of them carrying the account of the pair under the headline “Brides’s Death Ends a Theater Romance”, reporting that the pair had married some three months earlier. The local Colorado Sunday Gazette and Telegraph of February 5th 1905 includes a short death notice, with Lizzie being referred to under the professional name “Walters”

- Colorado Sunday Gazette & Telegraph February 5th 1905

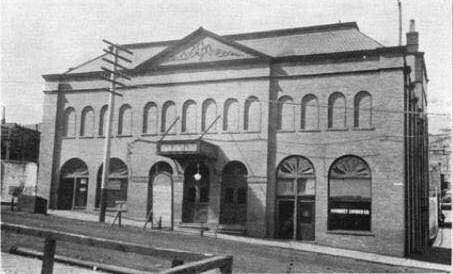

What Lizzie and maybe Walter, were doing in the gold-mining town of Victor is unclear, but there was an Opera House in the town at the time, that was on the Vaudeville circuit so she may well have been entertaining the mining community. Unfortunately, records for the cemetery were not kept and any that did exist cannot be located, the cemetery was never plotted and those arranging funerals could select whatever site, in whatever direction they preferred. A 1989 headstone survey of the cemetery does not include any mention of a grave for Lizzie.

- Victor Opera House – built 1902, destroyed by fire 1920

- Sunnyside Cemetery

British newspapers were not alerted to the passing of Lizzie until early March 1905 and the coverage was minimal, the following report is typical of how the press covered her death.

- Nottingham Evening Post – 4th March 1905

Papers held by the family have a slight twist on Lizzie’s death suggesting that she died in Chicago of peritonitis following a miscarriage, but this cannot be substantiated. So, in similar fashion to her sister Agnes, although at a much younger age, the Lizzie’s demise passes with little acknowledgement from the British press. The fate of her children is however well documented by their descendants; the father’s whereabouts being unknown, the children were effectively orphaned, although family documents suggest that their step-father wanted to be kept abreast of their fate but any actual interest, financially or otherwise failed to materialise. The plight of the youngsters was noted by the philanthropic Mrs Henry Fielding Dickens, daughter in law of the famous author, and they were admitted to a Dr Barnardo’s Home from where they were eventually sent to Canada in 1910 as two of the so called “Home-Children”.

My research on the life of Lizzie is ongoing and as more records come to light details of her life course can be confirmed, further established and hopefully significantly added to.

Article © Margaret Roberts

For more information on the Beckwith family see:

Day, D. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry – Frederick Edward Beckwith

Day, D. (2012). ‘“What Girl Will Now Remain Ignorant of Swimming?” Agnes Beckwith, Aquatic Entertainer and Victorian Role Model’. Women’s History Review 21(3), 419-446.

Day, D (2011). Kinship and Community in Victorian London: the “Beckwith Frogs”. History Workshop Journal 71 (1), 194-218