To read Part 1 of this series – please click HERE

One of the major challenges in researching the history of women’s football is trying to tell the individual stories of the players and officials. What makes the work of historians like Gail Newsham, Jean Williams and Gary James so special is that they have spoken directly to many of the players whose history they have been writing. Oral history is hugely important given the hidden nature of women’s football for much of the twentieth century.

For the Fleetwood Ladies we must focus on written records and sources. This is challenging. Newspaper reports reveal at least 25 named players, but this number is likely to be larger, since full-line ups were not always recorded for each game.

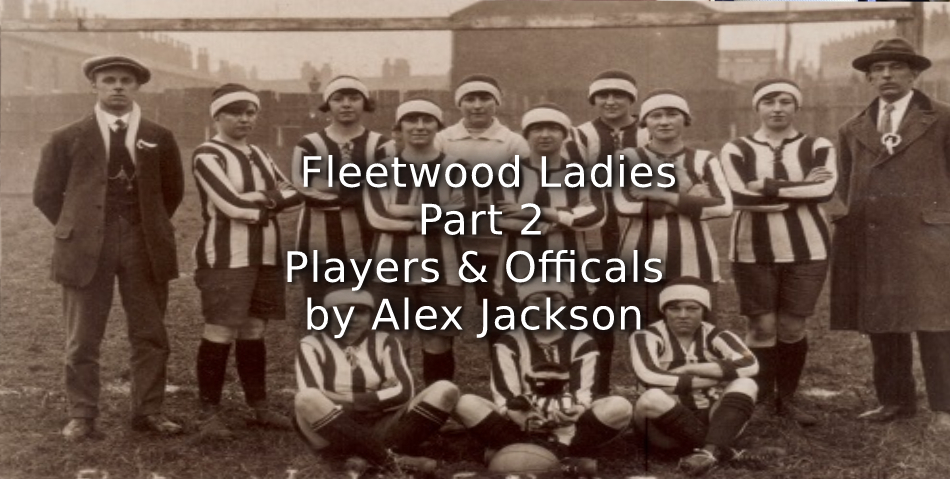

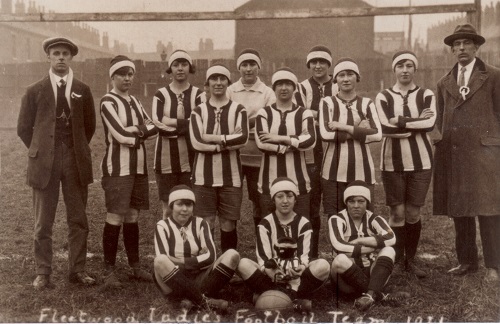

Fleetwood Ladies, 1921

Courtesy of Patrick Brennan Standing: Frank Porter, Martha Davis, Violet Brown, Gladys Holdsworth, Florrie Rance

Janie Collinson, Nellie Lively, Maggie Shaw, Nellie Sharp

Seated: Mary Willan, Annie Cullen, Mary Ellwood

Initial player identification by Patrick Brennan.

The postcard in the National Football Museum collection contains no information about the players. Thankfully, the Fleetwood Chronicle printed a different photograph of the team and crucially, added the full names of the players, not just their initials. Using this photograph, the historian Patrick Brennan has made an initial visual identification of the players.[1] Combining these photographs with digitised newspapers, it has been possible to find at least eight players and three officials in the 1911 census and the 1939 England and Wales Register. Together, these sources provide a starting point in sketching an outline of their lives.

Officials

Images believed to be of Jane Janet Lemon, James Henry Longworth, and Frank Porter

Burnley Express, 4 July 1921

Thanks to the British Newspaper Archive and the Johnston Press PLC and Patrick Brennan

The first match report mentions that the Secretary duties were undertaken by Miss J. Lemon.[2] Looking at the 1911 census, this may have been Jane Janet Lemon. She was a single 42-year-old, living with her sister and her brother-in-law’s family at 3 Plump Street, Fleetwood. The census did not provide an occupation, but her brother-in-law was a ships steward. In another photograph of the team, an older woman appears who looks like she could be Jane’s age in 1921.

Janet’s role as the Secretary was short-lived since an advert from February 1921 lists the secretary as H. Longworth. This was James Henry Longworth. In the 1911 census he was listed as a 48-year-old insurance collector, living with his wife, their four children, his brother, and four other boarders. They lived at 38 Victoria Street, just a few streets away from three different members of the team. As we can see in the map below, they lived near to the North Euston Ground, home of Fleetwood FC before the war and the site of three of the six games played by Fleetwood Ladies in their hometown.

The location of the North Euston Ground. Ordnance Survey Map of Fleetwood, 1914.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Given that many men scorned and derided the women’s game, why did James help the team? As an insurance collector he presumably possessed the skills and disposition for club administration. But then again, so did other men in Fleetwood. Why did he specifically choose to involve himself in the club?

Unlike officials at some other teams, he had no daughters playing in the team. Maybe he simply wanted to help or enjoyed being part of a club that was, however briefly, popular in the area. Or perhaps he was doing it as a favour to friends or family.

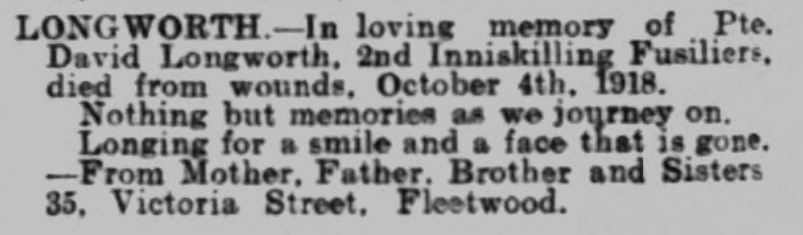

There is one other possibility. James is the first of several connections to the misery inflicted by the First World War. In August 1915, his youngest son, David, lied about his age to join the British army, aged just sixteen. He was one of an estimated 170,000 to 190,000 boys who successfully joined up.[3] David was discharged in August 1916, having apparently served seven months in France. In 1918 he was finally old enough and re-joined the army, either as conscript or as a volunteer. At this stage he was still too young for frontline service, which was still restricted to those above nineteen years of age. However, the German Spring Offensive of March 1918 led to this being reduced to eighteen years and seven months and later to eighteen years and six months. David was now eligible and was drafted to France, joining the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Inniskilling Regiment in the 109th Brigade, 36th (Ulster) Division. He was killed on the 3 October 1918.[4]

Like many women’s teams, Fleetwood Ladies helped raise for charities for Ex-Servicemen and War Memorials. Perhaps James’s involvement was one way of coping with the death of his son. Every year between 1919 and 1921 the family paid for David’s death to be mentioned in the Remembrance section of the Fleetwood Chronicle. They also paid over £1, a substantial amount of money for a working-class family, to add their own inscription to David’s headstone in Belgium.[5] All of this is circumstantial evidence, but it does provide a possible reason for why James involved himself in a club that raised an estimated £3,000 for charity.

Between 1918 and 1921, the Longworth family used the Fleetwood Chronicle to remember David’s death

Fleetwood Chronicle, 30 September 1921

Thanks to the British Newspaper Archive

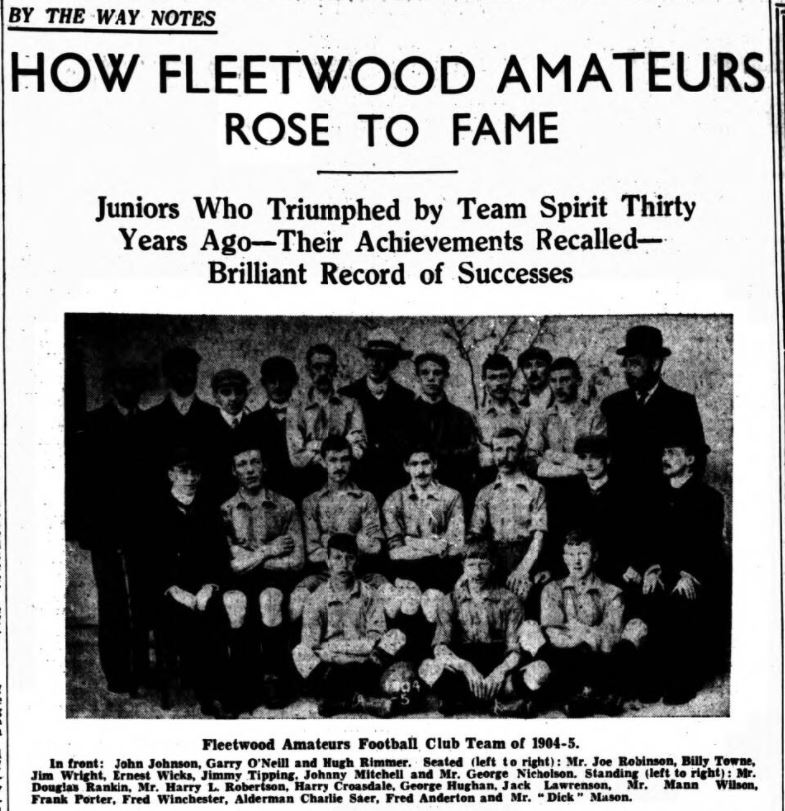

In the role of club trainer was Frank Porter, a former goalkeeper for Fleetwood Amateurs FC. In the 1911 census he was a 25-year-old labourer with a wife, two small children and a boarder. By the 1920s he was working as a meter inspector for the Fleetwood Gas Company and later became an electricity meter inspector for the Fleetwood Corporation.[6] Reports indicate that the team trained one night per week at the Market Hall.[7]

During the First World War male footballers had acted as trainers and coaches to women’s team. Frank was part of this wider trend of support, but we do not know the exact reasons why took on this role. Maybe he was friendly with the players or officials. Or perhaps, at the age of 35, he enjoyed being part of a club when his own playing days were presumably over or coming to an end.

Frank Porter in his playing days. He is fifth from the right on the back row

Fleetwood Chronicle, 3 May 1935

With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive

Players

Turning to the players in the team photograph, the 1911 census reveals that they were all children except for Nellie Sharp. She was then eighteen and living as a lady’s companion to Lucy Thurtle Chamney, a sixty-four-year-old widow of private means. Nellie is one of several players whose records yield no other connections to other documentary records on Ancestry, making them shadowy figures, at least until the 1921 census becomes available.

Almost all were born in Fleetwood to parents who were themselves born locally. The principal exception was Janie Gillet, who had been born in Dublin and whose mother was Irish. Several came from large families. Florence Rance was one of nine children between the ages of twenty-three years and six months, Jane Collinson was one of seven between four and twenty-three years old, while Janie Gillet was one of four between four months and seven years old.[8] Others came from smaller families: Martha Davis, Mary Ellwood, Gladys Holdsworth and Annie Cullen each had two siblings. The census also records that almost half the families had lost a child. The Rances’, Cullens’ and Davis’ each lost one, while the Collinson’s lost two.

Several of the team lived near to the club secretary James Henry Longworth. This is perhaps best seen in this google map which plots the locations of the players from the 1911 census.

https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=1uC9l874RBH8rwD4EtRZ4CDQ2h5AZiwQR&usp=sharing

Looking at their father’s occupations, we can see that all the players came from working class families.[9]

Fathers Occupations in 1911 census.

| Player (age) | Father (age) | Occupation |

| Jane Collinson (12) | Joseph (49) | Carter – general carrier |

| Annie Cullen (8) | Thomas (40) | Boiler-maker labourer |

| Martha Davis (8) | William (36) | Sheet metal worker |

| Mary Elizabeth Ellwood (7) | Daniel (38) | Fish packer |

| Jane Gillet (7) | John (43) | Fisher? |

| Gladys Holdsworth (10) | James (34) | Bootmaker and repairer |

| Florence Rance (10) | Charles (45) | Chemical Works Foreman |

| Nellie Sharp (18) | Not known | Not known |

| Mary Willan (5) | Joseph (28) | Yankerman (Anchorman?), sea-going |

Life for Jane Collinson and Mary Willian would have been particularly tough, since both their fathers died later in 1911. Mary’s mother, Sarah, would have been left to raise two children under the age of five. By 1921 Sarah had remarried. Jane’s mother might have expected help from her eldest son Joseph, who was then a 23-year-old dock labourer. But in 1916 he was killed serving in the Royal Naval Reserve, when his trawler, the “Sarah Alice”, was sunk with all hands by a German submarine. The Fleetwood Chronicle reported that, ‘a painful sensation was created in Fleetwood’ when news broke.[10] The Collinson’s were spared the loss of his younger brother, Tom, who served in the Railway Section of the Royal Engineers during the war. The Rance’s saw their son Thomas survive his service in the Royal Navy Reserve.

What occupations the players had in 1921 is at present unknown. Elder sisters in 1911 were employed as servants or housemaids, a common occupation for working-class women before the war. The First World War reduced the popularity of such jobs, but they remained a key area of employment throughout the inter-war period. A 1921 report mentions the team playing at the Docks during lunchbreaks but whether this meant that they worked in them or nearby is unclear.

What happened after they finished playing? Half of the players are recorded as having married or being in a relationship. The scale of lost male life in the First World War meant that the early 1920s saw the media sensationalise the idea of ‘surplus’ or ‘superfluous’ women.[11] However, remaining single was not unusual in the context of long terms demographic and marital trends. A pre-existing numerical gender imbalance had been evident for some time and up to a third of women between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-five were unmarried in the late nineteenth century. By 1930, half of women aged twenty-five to twenty-nine in 1921 were still unmarried. The Fleetwood players seem to broadly fit this trend, although it should be still noted that few seem to have had children. Mary Willan married at eighteen, while Mary Ellwood married at thirty-three and Gladys Holdsworth at forty-four.

| Player/age in 1911 | Marriage | Children in 1939 | Date of Death |

| Jane Collinson (12) | No record | 1969, January, Flyde | |

| Annie Cullen (8) | ‘Inferred’ spouse in 1939 Register | ‘Inferred’ daughter | 1988, July, Blackpool and Fylde |

| Martha Davis (8) | No record | 1988, November, Blackpool and Fylde | |

| Mary Elizabeth Ellwood (7) | No record | 1978, January, Fleetwood | |

| Jane Gillet (7) | 1937, October. Ireland | Unknown | No record |

| Gladys Holdsworth (10) | 1944, October. | 1992, June, Blackpool and Fylde | |

| Florence Rance (10) | No record | No record | |

| Nellie Sharp (18) | No record | No record | |

| Mary Willan (5) | 1924, July. | Hilda (6), Walter (3) | 1980, April, Fleetwood |

Some of the players appear in the 1939 National Register, almost all still living in Fleetwood. Martha Davis was single, living with her parents and working as a shop assistant and carpet sower. Jane Collinson was also single, working in the fish industry. Mary Ellwood was single and a housekeeper for her widowed father and two brothers. Annie Cullen was still living at the same address from 1911 with her widowed father and her brother William. The records note that she was living with an ‘inferred spouse,’ Francis Pinder, and an ‘inferred’ daughter, Mary Pinder. One who moved away for a while was Gladys Holdsworth. There is a record of an application to study Nursing in Edinburgh in 1928 and in 1944 she was married in Burnley.

From the available records, it seems most players remained in the Fleetwood area until their deaths. Without digitised copies of the Fleetwood Chronicle for the 1960s to 1990s it is impossible to say whether their passing was noted, nor whether memory of their playing exploits was recalled.

Not all the players were local. On the 21 May 1921, the Fleetwood Chronicle announced that two new players had been secured, although both had been playing since the start of the month. One was Miss L. Berkins who had played for Dick, Kerr Ladies, and Chorley. The other was Miss. P. Scott who had also played for Chorley. From other reports it is believed that her name was Polly. If we assume that she was a native of Chorley, there is a match in the 1911 census living at 13 Long Row, Botany, Chorley. This Polly was thirteen years old and one of eight children, aged between eight and twenty-five years old. Her father, George, was sixty-two and a boatman or Canal Captain, while her mother, Jane, was thirty-nine years old. Sadly, there are no links to any records after 1911, so we have no idea of whether she married or when she died.

Polly played at centre-forward and attracted enough attention to be invited by the Plymouth Ladies to play for them the latter part of 1921, including a tour to France with games in Le Havre and Paris. She was also selected for an English Women’s Football Association XI for a game with Grimsby & District on the 21 February 1922.[12] This brief playing career is revealing on several counts. In playing for three different clubs, two seemingly by request, it shows how links that were beginning to develop between teams and players in different parts of the country. It also suggests that some players were willing to travel considerable distances to get a game.

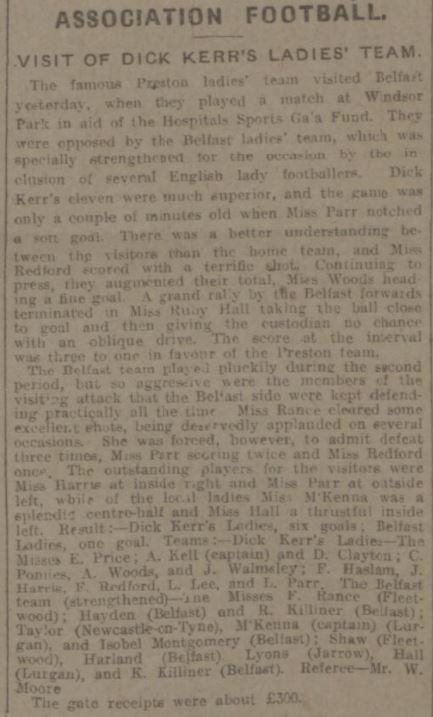

Polly was not the only player to appear for other teams. In October 1921, Florrie Rance and Maggie Shaw were invited to play for a reinforced Belfast team against Dick, Kerr Ladies FC. Presumably, they had impressed during their previous visits to Belfast. The game was again organised by Mrs Diana Scott and resulted in a 6-1 win for Dick, Kerr Ladies.[13] Interestingly, the Fleetwood Chronicle does not seem to have mentioned the game or their involvement. Given its interest in the team, it is surprising that it did not make anything of the growing popularity of these two players in the women’s game.

Florrie Rance and Maggie Shaw played for Belfast

Northern Whig, 27 October 1921

Thanks to the British Newspaper Archive

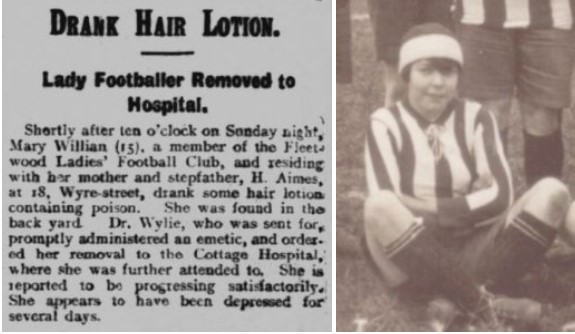

Of the inner lives of these players, the Fleetwood Chronicle yields few clues, except for one sad case. On the 8 April 1921, it reported that Mary Willan had been taken to hospital, following a serious act of self-harm.

Fleetwood Chronicle, 8 April 1921 [With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive]

Mary Willan, courtesy of Patrick Brennan.

All of this is an initial sketch of the players and officials. I hope that it will develop as more information comes to light. The 1921 census will provide further details and perhaps family relatives may be able to reveal more about the lives of those involved with this remarkable team.

Article © of Alex Jackson

Part 3 – Fleetwood Ladies: Media Coverage can be read HERE

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Steve Bolton and Professor Robert Hess for their help with these articles

References

[1] http://www.donmouth.co.uk/womens_football/team_gallery.html

[2] Fleetwood Chronicle, 31 December 1920.

[3] Richard Van Emden, Boys Soldiers of the Great War (Bloomsbury: London, 2012), pp.367-374.

[4] Details from the 1911 census, David Longworth’s Army Service Record (accessed via Ancestry), the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and the Fleetwood Chronicle, 11 and 18 October 1918.

[5] Families paid per letter to have an inscription of their choice added to the headstone.

[6] Fleetwood Chronicle, 21 January 1921 and 3 May 1935.

[7] Fleetwood Chronicle, 21 January 1921.

[8] Eight of the nine Rance children lived at home in the 1911 census. The eldest in 1901, Emma, was married by 1911.

[9] None of their mothers had an occupation listed.

[10] Fleetwood Chronicle, 3 October 1916.

[11] http://ww1centenary.oucs.ox.ac.uk/unconventionalsoldiers/%E2%80%98surplus-women%E2%80%99-a-legacy-of-world-war-one/#:~:text=More%20than%20700%2C000%20British%20men%20were%20killed%20during%20World%20War%20One.&text=Like%20the%20press%20in%20the,documented%20in%20the%201921%20census.

[12] http://donmouth.co.uk/womens_football/elfa.html

[13] Northern Whig, 27 October 1921.