Playing Past is delighted to be publishing on Open Access – Sporting Lives, [ISBN 978-1-905476-62-6] a collection of papers on the lives of men and women connected with the sporting world. This edited volume has its origins in a Sporting Lives symposium hosted by Manchester Metropolitan University’s Institute for Performance Research in December 2010.

Please cite this article as:

Porter, Dilwyn. The Reverend K.G.G. Hunt, Muscular Christian and Famous footballer, In Day, D. (ed), Sporting Lives (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2010), 40-54.

4

______________________________________________________________

The Reverend K.R.G. Hunt, Muscular Christian and Famous Footballer

Dilwyn Porter

______________________________________________________________

Ordained clergymen have not made much of a mark in professional football. Of the 16,151 players listed as having appeared in English Football League matches between 1888 and 1939, only four were ministers of religion.[1] The most famous of these was the Reverend Kenneth Reginald Gunnery Hunt (‘K.R.G.’) who played 61 league and cup matches for Wolverhampton Wanderers, mainly between 1906 and 1909, making his last appearance for the club at the age of 35 in 1919. Hunt, an uncompromising half-back who retained amateur status throughout his playing career, was capped twice by England at full international level, appearing against against Wales and Scotland in 1911. He also made at least twelve appearances for England in amateur international matches and was a member of the teams that represented Great Britain at the London Olympic Games in 1908 and at Antwerp in 1920.[2]

Though we will begin with a brief account of his playing career, our chief concern here is with Hunt as a writer on football. His achievements as a player gave him credibility as an author and this was augmented by the moral authority derived from his status as a cleric. As far as publishers were concerned, it was an attractive combination. He first outlined his views on how the game should be played in three articles for the Boy’s Own Paper in 1915-16 entitled ‘How to Become a Football Star’. In 1922-23, he followed this up with three more, in the form of letters to the ‘Captain of Footer’ at the imaginary ‘Severn Side School’.[3] By then, Hunt had written his first book, Association Football, published as part of a series comprising ‘Popular Handbooks on Athletic Sports’ in 1920 and reproduced in a slightly expanded second edition three years later. Another book, First Steps to Association Football, followed in 1924.[4] Football: How to Succeed, a 32-page pamphlet with a preface by the secretary of the English Schools Football Association (ESFA), was published in 1932.[5]

Hunt’s career as a footballer c.1904-20

Hunt achieved a distinctive profile as a player on account of his prominence at the highest levels of both professional and amateur football. He first attracted attention when representing Oxford University, where he was a regular at wing-half between 1904 and 1908, playing in four varsity matches and finishing on the winning side in three.[6] It was while he was at Oxford that Hunt first appeared for the elite Corinthians club, making his debut against Woolwich Arsenal on Boxing Day 1905 and later joining them for a continental tour in 1906 which ended with a victory over the Dutch national side.[7] Hunt, even at 21, was regarded as an outstanding footballer and made his first appearance for the England amateur representative team in 1907 while still an undergraduate. Selection for the Olympic squad that won the tournament at the White City in October 1908 was a natural progression.

By then, however, it was what Hunt had achieved while playing alongside professionals at Wolverhampton Wanderers that seemed more significant. His father had become vicar of St Marks, Wolverhampton in 1898 and Hunt was educated at the local grammar school before leaving in 1902 to become a boarder at Trent College. The local professional club, then in the Second Division of the Football League, was delighted that a player of his calibre was sometimes available for selection and he was able to play a major part in the campaign that led to victory in the Football Association (FA) Cup Final in April 1908. Wolves’ 3-1 win over Newcastle United, a powerful First Division side and clear pre-match favourites, owed much to Hunt, who opened the scoring with a speculative shot from 40 yards. Seasoned observers attributed Wolves’ success to ‘the overpowering character of their first class half-backs’.[8] By 1908, the FA Cup Final was a sporting fixture of national significance and Hunt became something of a celebrity. In his home town he was feted as a hero, with Wolves loyalists eager to point out that he had ‘learnt his craft as a footballer at the Grammar School and not at Trent College’.[9] In this respect Hunt seems to have been representative of an era ‘when provincial towns produced and cherished their own great men’.[10]

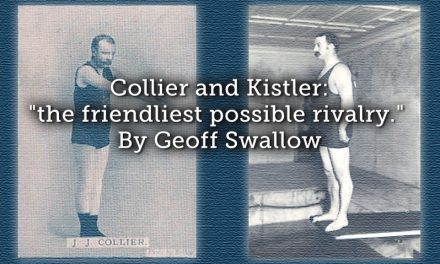

Figure 1.

Wolverhampton Wanderers at the start of Hunt’s great season, 1907-8

Hunt, back row, fourth from left, adopts the casual pose characteristic of the gentleman amateur, hands in pockets

Source: Wolverhampton Archives and Local Studies, DX-212/1/2

Though it was not unknown for gentleman amateurs to play with professionals at this time – C.B. Fry had appeared many times for Southampton – it would not have occurred to Hunt that he should make a living from the game at which he excelled. A few months after his success with Wolves, he embarked on a conventional career for a young man of his social and educational background when he took up a teaching post at Highgate School in London. In 1909 he entered Holy Orders, following his father into the Anglican ministry, but did not seek a parish and was content to remain at Highgate until his retirement in 1945. Though he continued to turn out occasionally for Wolves, he chose to play most of his football in the years before the First World War for Leyton, then a professional club in the Southern League. Charles Buchan, who played for the East London club before moving on to Sunderland, Arsenal and England, later recalled Hunt’s influence on him as a young player: ‘It was Hunt who instilled in me the art of positioning. In his quiet voice he would tell me where to go when he had the ball, or where to position myself when we were on the defensive’.[11]

Figure 2

Local hero: FA Cup winner with Wolves, 1908

Source: Wolverhampton Archives and Local Studies, DX-1036/3/3

Like many gentleman amateurs, Hunt was noted for his robust play. Buchan remembered that he liked to make use of ‘an honest shoulder charge, delivered with all the might of his powerful frame’. The convention in English football before 1914 was for wing-halves, rather than full-backs, to mark wing-forwards, and Hunt’s physicality undoubtedly made an impression. Billy Meredith, an outstanding winger for Manchester City, Manchester United and Wales, later told Buchan, ‘I never ran up against a harder or fitter half-back. It was like running up against a brick wall when he charged you’. [12] It is possible, however, that Hunt came to rely rather too much on this aspect of defensive play. After leaving Leyton, he played for Oxford City, members of the Isthmian League, assisting them in their run to the FA Amateur Cup Final in 1913. It was reported that the referee for the replayed final against South Bank ‘took exception to the Rev Hunt’s persistent shoulder-charging’, and this may have contributed to City’s defeat.[13] Hunt may have had this unhappy experience in mind years later when he was ‘delighted to see signs that referees are becoming more friendly to charging than they were’.[14]

Hunt seems to have liked the idea that he was free to accept invitations to turn out for any side and played for Eccleshall Comrades at Christmas 1918, presumably while staying with his father who had by then moved to the Staffordshire village. He appeared for both Wolves and Crystal Palace in 1919-20, the first full season after the war, but mainly for the Corinthians, though both he and they were past their best by this time. His retirement from senior football seems to have come after he had played for the Great Britain side that was eliminated in the first round of the 1920 Olympic tournament.[15] Thereafter, he pursued his interests in the game mainly as master-in-charge of football at Highgate, where he assembled a succession of teams that dominated English public schools soccer in the 1920s and 1930s. Highgate’s old boys team, the Old Cholmelians, also enjoyed considerable success in this period.[16] Hunt’s playing days were over before the offside rule was reformulated in 1925 and he was unhappy with some of the tactical changes that followed but his credibility as an authority on how to play the game remained intact. Under the direction of Stanley Rous after 1935, the FA began to take coaching seriously, establishing training courses for coaches. Rous claimed that ‘this was a new idea for any sport’. Hunt had a part to play in this initiative and was used as a technical advisor for at least one of the FA’s instructional films.[17]

Hunt’s advice to young footballers

The Boy’s Own Paper, founded in 1879 and published by the Religious Tract Society, was the perfect vehicle for Hunt’s first efforts as an author. Its contents – improving tales of pluck and derring-do alongside features on hobbies, scouting and sport – were designed to appeal to a core readership of public schoolboys and also to their parents, who often bought the magazine for them. The monthly issues, attractively bound as the Boy’s Own Annual, made an acceptable Christmas or birthday present. By the early twentieth century, as the impact of the 1870 Education Act on mass literacy became increasingly apparent, its readership had expanded and ‘B.O.P.’ (as it was known to its readers) began to attract boys from grammar and state schools with pocket-money to spend.[18] Though Hunt always had the public schoolboy in mind when he wrote, he seems to have been aware from the start of this wider audience.

Hunt was one of a number of sporting celebrities who contributed to ‘BOP’ and his credentials – ‘by the Rev KRG Hunt (English International, 1906-13)’ – were prominently displayed at the head of each article. ‘How to Become a Football Star’ appeared in three parts from November 1915 to January 1916. The first, entitled ‘Captaincy – Coaching Hints – Play in General’, comprised advice to the captain of a school team, a literary form to which Hunt would return. It opens with Hunt’s musings on the captain’s role. ‘An ideal boy skipper’ was ‘very hard to find’, he conceded, but perhaps this was because the qualities required were so many and so varied:

… for your school skipper must be a many sided person. He must of course be a sound performer himself, but in addition to this he must know the game thoroughly, and by this I mean that he must not only know his own duties as a centre-half or full-back, or whatever he may be, but he must know what each member of his side individually, and what the whole team collectively, should do and can do.

The ‘boy skipper’ was also expected to study the strengths and weaknesses of opponents and to plan accordingly.[19] Taken as a whole, this was the kind of thinking to which junior officers undergoing staff training in the armed forces were routinely exposed and it is difficult to separate Hunt’s ideas on captaincy from their wartime context, or indeed from his role as Lieutenant of Highgate’s Officer Cadet Corps attached to the Third Volunteer Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment.[20]

Though Hunt advised captains of football not to push their teams too hard in training, he valued exercises that would encourage boys to develop their ball skills. ‘Perhaps the most valuable practice that a boy can get’, he advised, ‘is to take a tennis-ball into an old fives court’, before noting that the Eton fives court, which incorporated a buttress, was ‘almost useless’ for this purpose. At this point, Hunt risked losing an important part of his audience – boys with no experience of public school life who would never have seen a fives court – but he rose to the challenge.

At many schools will be found an asphalt playground bounded on at least one side by a brick wall. Like the fives court, this may be a valuable asset in teaching the game to a school side. No better idea of the perfection of forward play as practised by the Corinthians can be given than when a boy tries to dribble along such a playground, passing the ball to the wall, receiving it as it rebounds, and immediately passing it back again.[21]

Even a working-class boy could thus aspire to play like the cream of gentlemen amateurs.

Hunt’s first series of articles introduced other themes that were to feature in the books he wrote later. His Christian faith was of the muscular variety that underpinned the ideology of sport emanating from the public school system. As Richard Holt has argued, this was connected with a redefinition of masculinity as English public schools and the grammar schools that imitated them sought ways of shepherding adolescent boys safely through puberty. Games played an important part in distracting boys from ‘impurity’ in its various forms while simultaneously building ‘character’.[22] As far as sport was concerned, the ‘give and take’ attitude that it was said to foster was a significant learning outcome, a key stage in the process of converting a boy into a man, or more specifically, an Englishman. The objections raised at the first meeting of the FA in 1863 to those who opposed ‘hacking’ (i.e. shin-kicking) come to mind here. ‘If you do away with it’, a representative of the Blackheath club had argued, ‘you will do away with all the pluck and courage of the game, and I will be bound to bring over a lot of Frenchmen who would beat you with a week’s practice’.[23] In his article on the art of defence, published in December 1915, Hunt’s advocacy of the ‘honest shoulder-charge’, seems rooted in the same set of beliefs. It was ‘not only legitimate, but has done very much to make the game the manly sport that it is’. If it was eliminated, he added mysteriously, ‘something far less harmless will creep in’.[24]

‘Captain of Footer’, Hunt’s second series for Boy’s Own Paper, published between November 1922 and January 1923, covers similar territory. Just as it is possible to read some of the preoccupations of a nation at war into Hunt’s first series, these letters from an ‘affectionate uncle’ are indicative of anxieties arising from the political and social tensions that characterised Britain in the 1920s, the decade of the General Strike. The first is mainly devoted to Hunt’s thoughts on relations between the middle-class amateur and the working-class professional. ‘James Macalister Brown’, the boy skipper at Severn Side, to whom the letters are addressed, had been invited to sign as an amateur for ‘the Rovers’, his local professional club. Hunt’s comments focus on the soul-searching that would inevitably ensue. ‘Now Jim’, he wrote, ‘… I fancy this invitation is flattering to your soul, but that while inclination prompts you to accept, you fear you may lose caste with some of your fellows if you play with the pros’. He urged him, however, to put his doubts aside.

You and I know, of course, that there are things in pro footer that we don’t like, but if fellows who have had the good fortune to be born under a lucky star, and to go to a public school like Severn Side, and afterwards to Oxford … are going to give themselves airs and think themselves above playing with the pros, then who can wonder if pro-football is dirty.

For Hunt, it was clear that young James had much to offer the professional game, notably moral leadership and brains. ‘You will teach these fellows something of the Public School spirit’, he argued, ‘just as they will certainly teach you something of football’. ‘Candidly’, Hunt continued, ‘I don’t think they will teach you much as to tactics, but I shall be surprised if they do not speed you up a great deal’.[25] In all this, it is possible to detect an effort to reach across the social and political chasm then separating the middle-class from the working-class. While we know little of Hunt’s politics, we do know that he was quick to distance himself from middle-class footballers who looked down on their working-class counterparts. He had, after all, preferred to mix with the professionals at Wolves and Leyton in the period of English soccer’s ‘great split’ between 1907 and 1914 rather than play for a socially-exclusive amateur club such as the Corinthians.[26] Later, during the 1930s, while serving on an Amateur Football Alliance committee, he made a point of disassociating himself from a colleague who talked down to the secretary of a working-men’s club.[27]

This is not to say that Hunt ever detached himself from his class and the public school system in which he felt comfortable. The books and pamphlets that he wrote in the 1920s and early 1930s were addressed to schoolboy footballers – principally those at public schools – and to those who continued to play as young men. Though he was no snob, there was an underlying assumption that the game as played by public schoolboys, varsity men and gentlemen amateurs before the Great War, represented football at its best. In Association Football, for example, he acknowledged that it was now unfashionable for wing-haves to mark wing-forwards, as he had once marked Meredith, but noted that it was still favoured in ‘the best type of amateur football’.[28] As far as Hunt was concerned, there was no doubt as to where this was to be found.

Much of Hunt’s advice to defenders related to the importance of ‘combination’ play, with team-mates adjusting their positions so as to frustrate oncoming forwards, but he tended to look to the gentlemen amateurs of the pre-war era, rather than the professionals of the post-war era for inspiration. Defensive combination, he argued, had been developed to perfection by A.M. and P.M. Walters, while playing at full-back for the Corinthians in the 1880s. One would always play a little in front of the other, making the initial challenge that would cause an opponent to lose control of the ball, thus allowing his partner to step in and clear. ‘I am afraid’, Hunt added ruefully, ‘that the Walters’ play would be too vigorous to suit modern players or referees, which is a pity, for their hefty charging did a great deal for the game’.[29] With full-backs assigned to the last line in defence, the centre-half was free to join the attack; he was ‘the only player who can roam practically all over the field, and yet be doing his job properly’. As late as 1932, when ‘stoppers’ like Herbie Roberts of Arsenal, had became commonplace in English football, Hunt was still arguing that the centre-half should have a creative role – ‘because your centre-half should be the flywheel of the whole team and around him the whole team should revolve’.[30]

As far as attacking play was concerned, Hunt favoured the long ball, making strategic use of diagonal passes to demoralise the opposing defence. ‘Nothing discourages a back … so much’, he noted, ‘as to chase out some forty yards or so after a wing forward, only to find the latter slinging the ball across just before he can be tackled’.[31] On a more pragmatic level, he argued that attacks which relied on combinations of short passes were more likely to break down, especially in English conditions. Moreover, the short-passing style required players with above average technique if it was to be played successfully, and these were in short supply. ‘On the whole’, he wrote of the long-ball game, ‘it is an easier game to play, for there is not the same need of accuracy, and against some types of defence it pays all along the line’.[32] One senses that Hunt’s ideas on tactics would have been sympathetically received by Stan Cullis, manager of the successful Wolves teams of the 1950s, who also preferred a direct approach. ‘Tip-tap, tip-tap’, Cullis would murmur in frustration, when his players knocked the ball around in midfield.[33]

Hunt’s views on passing would strike observers of the modern game as eccentric: he thought that there was far too much of it and regretted that dribbling with the ball, which allowed a player to express his individuality, was becoming a lost art. Though he would have adopted a different formation to that employed by the Corinthians, he would certainly have approved of their method of attack ‘with long sweeping passes usually into space, for a colleague to run onto’.[34] There was, however, a moral viewpoint lurking behind these observations. In Association Football, he had insisted that the forward who spurned an opportunity to shoot in favour of a pass was guilty of ‘moral cowardice’.[35] He later developed this idea in First Steps to Association Football. ‘Passing’, he advised his readers, ‘is only a means to an end, and that end should never be – as it so often is – the shifting of your own responsibility onto someone else’s shoulders’.[36] There is a slight but significant pre-echo here of some contributions to the debate regarding the respective merits of ‘individualist’ as opposed to ‘collectivist’ football that surfaced when Moscow Dynamo came to Britain in 1945 and again when England played Hungary in 1953.[37]

The most explicit statement of Hunt’s muscular Christianity is to be found at the start of Football: How to Succeed, which was targeted at ‘youngsters just starting the game’. Winning, was important – (‘You will want to win – we all do’) – but not at all costs.

How often, especially in Cup-ties, we see a side that is leading by one goal kicking the ball into touch, and resorting to other tactics of this sort calculated to waste time. If you are sportsmen you will find small satisfaction in a victory won by such means.

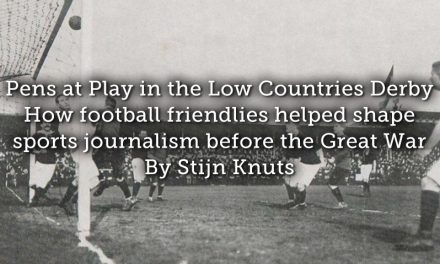

Figure 3

When tackling, Hunt favoured a technique he had learned from M. Morgan-Owen of the Corinthians in the early years of the twentieth century. This involved blocking the ball with both feet while leaning into an opponent.

Source: Reverend K.R.G. Hunt, Football: How to Succeed (London: Evans Brothers Ltd, 1932), 16-17.

Playing the game in the right spirit was what really counted and this meant avoiding the various temptations that would inevitably arise over the course of 90 minutes. A defender, for example, who might be tempted to block a goal-bound shot with his hands, was urged not to yield. Though his action might save the match,‘he [would lose] his reputation as a sportsman’. Hunt was bringing to a wider audience the kind of advice that he might have given a public schoolboy who had let himself down by misabehaving in a house match. ‘It is a great thing to play in a successful side’, he continued, ‘but it is a far greater thing to play in a side that has a reputation for sportsmanship and fair play’.[38]

Football, it seemed, could supply the kind of testing environment in which character was formed. ‘Observe the spirit of the game as well as the letter of the law, and learn to be undiscouraged by defeat’, wrote Hunt, ‘just as I hope you will be chivalrous in victory’.[39] Hunt’s reputation as a footballer – his England caps and FA Cup winner’s medal – lent authority to this neat restatement of the Corinthian ideals with which every public schoolboy would have been familiar. But he was also writing as ‘Rev. K.R.G. Hunt’ and this added a spiritual dimension to his thoughts on how football should be played. This was underlined by T.P. Thomas of the ESFA in his foreward to How to Succeed. ‘So when you leave school and become a Junior or even a Senior player’, he urged, ‘remember that the “straight game”, as the Rev K.R.G. Hunt says, is the only game to play’. Here was soccer’s equivalent of learning how to play cricket with a straight bat, a moral compass that would serve a chap well as he made his way in life.

Conclusions

This essay has supplied a preliminary assessment of Hunt’s contribution to English football. Though his articles and books provide clues, further research is required to reach an understanding of what Hunt was like as a coach. Yet it is possible to draw some provisional conclusions regarding the historical significance of his published work. Perhaps the most obvious is that Hunt’s observations confirm the impression that gentleman amateurs – especially defenders – were often very physical in their approach to football. The application of muscle, however, did not preclude thinking strategically about the game. Even though Hunt favoured the the long ball, he made it clear that there was little to be gained from the hopeful punt upfield. ‘Always remember’, he warned, ‘that there must be just as much method in the long passing as in the short passing game’.[40] Hunt’s advice to defenders – that they should maximise their strength by pivoting simultaneously to meet the point of a developing attack – owed something to science. There was more to defending than the manly shoulder charge and an uncompromising method of tackling that Hunt had learned from Morgan-Owen of the Corinthians ‘in the very early years of [the] century ’.[41] Football required both brawn and brains and it was the the role of the well-educated, middle-class player to provide the latter. Writing in 1924, at the end of a season in which England had finished last in the Home International Championship , he reminded his readers – ‘especially the Public School element’ – that ‘the brainy player is needed more than ever if the game is to be restored to its old place’.[42]

Restoring soccer to ‘its old place’ had become especially important for Hunt and other advocates of the association game in the 1920s and 1930s when there was a discernible ‘rush to rugby’ in the public and grammar schools. Ross McKibbin has argued that this was ‘an overt statement of deliberate class-differentiation’, part of ‘the middle class reaction to an apparently politicized and aggressive working class’. [43] Whatever the causes of this trend, it was clear that many headmasters now believed that rugby union was ‘unequalled by any other game as a school of true manhood and leadership’.[44] As far as Hunt was concerned, this was regrettable for two reasons. At the peak of his powers, he had been one ‘of a small and dwindling number of exceptional amateurs’ playing at the highest level.[45] If this pool of middle-class talent dried up, he feared for the future of English football ‘for the old Public Schoolboy has invariably provided that spice of originality which may yet lift the game from that mediocre level to which it appears to have sunk’.[46] This was the important contribution which young James Macalister Brown could make by playing with the ‘pros’ at the Rovers.

Underpinning this concern, however, was an issue of wider importance. ‘If Rugby’, Hunt argued, ‘is to become the game of the Public Schools and Soccer is to be left entirely to the working classes, we are deliberately severing one of the chains which still serve to hold the classes and the masses together’.[47] As Tony Collins has indicated, this idea was to be powerfully restated by defenders of public school soccer at the Headmasters’ Conference in 1925.[48] It is important to read his advice to young footballers in this context. Maintaining social cohesion seems to have been as important for Hunt as ensuring that boys acquired technical skills and tactical awareness. By restating the values of nineteenth-century muscular Christianity and realigning them with twentieth-century soccer, Hunt sought to ensure that the people’s game would survive in the top people’s schools.

References

[1] Michael Joyce, Football League Players’ Records 1888-1939 (Nottingham: SoccerData Publications, 2002), 5, 124.

[2] The most comprehensive biographical source for Hunt is Patrick A. Quirke, The Reverend Kenneth Hunt: ‘Wolves Footballing Parson’, http://www.localhistory.scit.wlv.ac.uk/genealogy/KennethHunt.htm (accessed 26 November 2010).

[3] K.R.G. Hunt, ‘How to Become a Football Star’, Boy’s Own Annual, XXXVIII, (1915-16), 20-1, 106-7, 163-4; ‘Captain of Footer. Being Letters from his Uncle to James Macalister Brown, of Severn Side School’, Boy’s Own Annual, XLV, (1922-23), 34-5, 129-30, 190-1.

[4] K.R.G. Hunt, Association Football (London: C.A.Pearson Ltd, 1st edn., 1920; 2nd edn., 1923); First Steps to Association Football (London: Mills and Boon, 1924).

[5] Football How to Succeed (London: Evans Brothers Ltd, 1932). Recent evidence suggests that this was first published in 1931 in association with the National Union of Teachers; see http://mirror football.co.uk/opinion/blogs/got-not-got/How-to-put-some-crunch-in-your-tackle-by-Wolves-star-the-Rev-K-R-G-Hunt-article161036.html (accessed 27 November 2010).

[6] Colin Weir, The History of Oxford University Association Football Club 1872-1998 (Harefield: Yore Publications, 1998), 28-9; see also Ian M. Sorenson, ‘Oxford and Cambridge’, in A.H. Fabian and Geoffrey Green (eds), Association Football (London: Caxton Publishing Co., 1960), vol. 2, 151-2.

[7] Rob Cavallini, Play Up Corinth: a History of the Corinthian Football Club (Stroud: STADIA, 2007), 85-6, 244.

[8] Sir Frederick Wall, 50 Years of Football 1884-1934 (Cleethorpes: Soccer Books Ltd, 2006), 159; first published in 1935; see also J.A.H. Catton (‘Tityrus’), The Story of Association Football (Cleethorpes: Soccer Books Ltd, 2006), 89; first published in 1926.

[9] See Quirke, Kenneth Hunt, chapter 4. Hunt’s caps, medals and other memorabilia are on display at the Molineux Stadium; see Tony Matthews, The Legends of Wolverhampton Wanderers (Derby: Breedon Books, 2006), p.113. For the blue plaque commissioned by the Wolverhampton Civic Society, see www.cityofwolverhampton.com/ Plaque%20Book%202009.pdf (accessed 27 November 2010).

[10] See John Arlott, Jack Hobbs: Profile of the Master (London: John Murray and Davis-Poynter Ltd, 1983), 20.

[11] Charles Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (London: Pheonix House Ltd, 1955), 23. Leyton (‘The Lilywhites’) are not to be confused with Leyton Orient (‘The Os’), a different club, then playing as Clapton Orient.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Bob Barton, Servowarm History of the F.A. Amateur Cup (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: privately published, 1974), 69.

[14] Hunt, How to Succeed, 17.

[15] See http://www.eccleshallpast.org.uk/eccleshall (accessed 11 December 2010); Joyce, Players’ Records, 124.

[16] Geoffrey Green, ‘The Romantic Driving Force of the Public Schools’, in Fabian and Green (eds), Association Football, vol, 2, 101-3.

[17] Sir Stanley Rous, Football Worlds: a Lifetime in Sport (London: Faber and Faber, 1978), 58-9; Quirke, Kenneth Hunt, ch.6.

[18] See Mary Cadogan, Frank Richards: the Chap behind the Chums (London: Viking, 1988), 40.

[19] Hunt, ‘How to Become a Football Star’, 20-1; first published in the Boy’s Own Paper, November 1915.

[20] Quirke, Kenneth Hunt, ch.6.

[21] Hunt, ‘How to Become a Football Star’, 20-1.

[22] See Richard Holt, Sport and the British: a Modern History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 86-98; see also David Winner, Those Feet: a Sensual History of English Football (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Ltd, 2005), 9-29.

[23] Cited in Geoffrey Green, ‘’The Dawn of Football’, in Fabian and Green (eds), Association Football, vol.1, 52.

[24] Hunt, ‘On the Defence’, 107; first published in Boy’s Own Paper, December 1915.

[25] Hunt ‘Captain of Footer’, 34-5; first published in Boy’s Own Paper, November 1922.

[26] For the social basis of the schism see Dilwyn Porter, ‘Revenge of the Crouch End Vampires: the AFA, the FA and English Football’s “Great Split”, 1907-14’, Sport in History, 26, no. 3 (2006), 406-28.

[27] Walter Greenland, The History of the Amateur Football Alliance (Harwich: Amateur Football Alliance/Standard Publishing Co., 1965), 74.

[28] Hunt, Association Football (1923), 31-2; see also First Steps, 34.

[29] Hunt, Association Football (1923), 20. Significantly, the Walters brothers were noted – and sometimes criticised – for their vigorous shoulder-charging. See Neil Carter, ‘Football’s First Northern Hero? The Rise and Fall of William Sudell’, in Stephen Wagg and Dave Russell (eds), Sporting Heroes of the North (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Northumbria Press, 2010), 135.

[30] Hunt, How to Succeed, 26. For details of the new offside rule and the tactical innovation that followed see Jonathan Wilson, Inverting the Pyramid: the History of Football Tactics (London: Orion, 2009), 42-51; Matthew Taylor, The Association Game: a History of British Football (Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd, 2008), 221-2; Dave Russell, Football and the English: a Social History of Association Football in England, 1863-1995 (Preston: Carnegie Publishing, 1997), 84-5.

[31] Hunt, First Steps, 67-8.

[32] Hunt, Association Football (1923), 59-60.

[33] See Ronald Kowalski and Dilwyn Porter, ‘England’s world turned upside down? Magical Magyars and British football’, Sport in History, 23, no.2 (2003-4), 44.

[34] See Tony Mason, Association Football and English Society 1863-1915 (Brighton: Harvester Press, 1981), 216.

[35] Hunt, Association Football (1923), 54.

[36] Hunt, First Steps, 78-9.

[37] See Ronald Kowalski and Dilwyn Porter, ‘Political Football: Moscow Dynamo in Britain, 1945’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 12, no.2 (1997), 110.

[38] Hunt, How to Succeed, 3.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Hunt, First Steps, 68.

[41] Hunt, How to Succeed, 16-17.

[42] Hunt, First Steps, 11-13.

[43] Ross McKibbin, Classes and Cultures: England 1918-1951 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 350-1.

[44] See Taylor, Association Game, 122-3; also Rous, Football Worlds, 45-8.

[45] Russell, Football and the English, 45.

[46] Hunt, First Steps, 11-13.

[47] Ibid.

[48] See Tony Collins, A Social History of English Rugby Union (London: Routledge, 2009), 65-8.