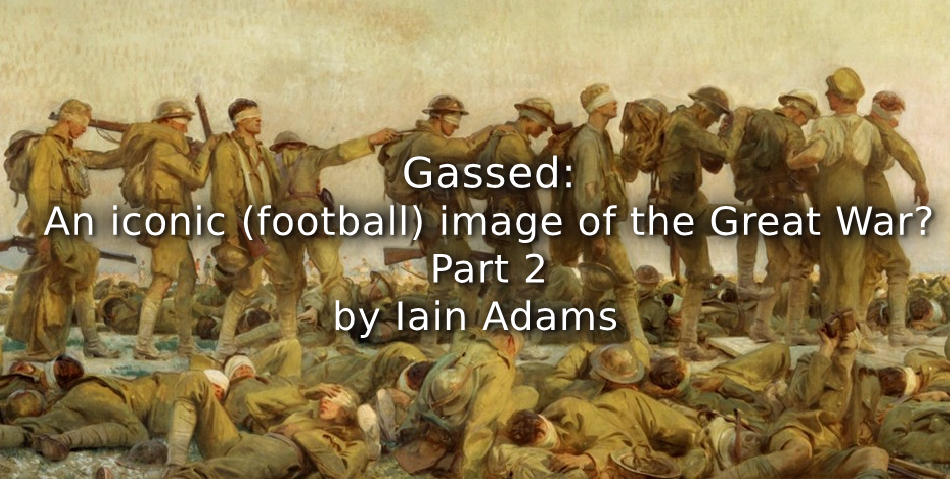

This article explores the contentious meanings of the football match in John Singer Sargent’s ‘Gassed’ alongside identifying the stage and actors.

To read Part 1 click HERE

Football

The Times first report of the 1919 Academy Exhibition noted that ‘far behind are soldiers playing football; and this background is a kind of counterpoint to the procession of pain in front.’[i] Many viewers, focussing on the suffering in the foreground, miss the football match being played in the sun altogether. Kilmurray and Ormond simply note that ‘a football game can be seen taking place behind’ (Figure 8). However, this image of a football match has provoked discussion over the years. Some commentators see the football match as a symbol that ‘life goes on’.[ii] This has been interpreted as indifference or compassion fatigue among the medical staff to their comrades’ suffering. Brandon opined the painting included ‘the living and the disengaged’.[iii] Others believe it is a metaphor for the unconcern of the Government, the War Office and the local High Command to large scale suffering. Yet others have opined that the match is an indication of the traditional link between sport and war in Britain, a metaphor for the sporting spirit carrying on in the face of adversity.[iv] More recently some revisionists have interpreted the match from the opposite perspective as being a demonstrable effort by Higher Command to improve soldiers’ welfare and fitness for duty.

Figure 8. John Singer Sargent, Gassed.

Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum (IWM Art 001460)

Throughout World War I, football was a feature of life in the British army; it was seen to improve a soldier’s health and fitness, keep him out of bars and brothels, improve his relationships with officers and, create and maintain esprit de corps. In 1914 football was unofficial but Captain James Jack, the 1 Cameronians’ ‘C’ Company commander, noted ‘games, mainly football, in the afternoons keep them fit and cheery … however tired the rascals may be for parades they have always energy enough for football.’[v] By 1915, commanding officers were realising the potential of football to revitalise troops coming from the front line allowing ‘above all a brief mental escape from stress and horror’.[vi] The House of Commons recognized in March 1916 that men injured whilst playing games when off duty and on active service should be entitled to pensions or compensation if unable to return to service because ‘it is a part of the policy of the Army to encourage men to do everything to keep themselves in a condition of physical fitness. Consequently when a man goes bathing and when he plays football he is doing something to keep himself physically fit for military service.’[vii]

Lieutenant-General Maxse issued platoon training instructions in February 1917 commanding that physical training programmes were to include ‘recreational training such as football’.[viii] James Jack, by 1917 the 2 West Yorkshires Colonel, recorded ‘little as is the time for recreation, games have to be sandwiched in somehow, since no British troops ever travel without footballs or the energy to kick them’.[ix] Football was ubiquitous across the British army when Sargent was in France in 1918. Perhaps the team strips indicate this is not a kick-about but possibly a match between sections, platoons or companies. The lack of spectators suggests it is not a Brigade or Divisional game as spectators were an institutionalized element of that level of game by 1916 and that level of competition would not be normally scheduled during a major battle.[x] Sargent had a reputation for painting what he saw but as he was not a realist, he interpreted what he saw. Therefore it is possible that the men were just involved in a kick-about and playing in their uniforms as Bone had seen in 1916 (Figure 3). Sargent may have noted men playing football and this was the interpretation of his notes in his studio in 1919.

Other reviewers see the football match as a symbol of Home Front innocence to the reality of war, but Sargent has not included spectators who would surely represent those at home watching the action. In fact, he deliberately left out a traditional artistic emblem of innocence – children. In a letter to Charteris, Tonks regretted that Sargent ‘did not put in something I noticed, a French boy and girl of about 8 years, who watched the procession of men with a certain calm philosophy for an hour or more, it made a strange contrast.’[xi]

The soldiers and medical staff assigned to Advanced Dressing Stations (ADSs), CMDSs, CCSs and other medical units were no different from other British army units. The staff had to be kept fit, develop team spirit and escape the pressures of their jobs. During the third Battle of Albert, Number 19 CCS had four surgical teams working by day and three by night, operating 12 hour shifts from 8 am to 8 pm and 8 pm to 8 am.[xii] Howard Somervell, a surgeon attached to 34 CCS recalled how the stress was intense and unending as they worked around the clock dealing with ‘an endless flow of carnage … smocks drenched in blood, with the nauseating scent of sepsis and cordite and human excrement’. In response to the strain, staff sought ‘to find their own peace in the midst of the madness. Somervell escaped with fellow officers to ‘picnic in the copses of oaks and maples behind the line … where larks and robins sang, and the dread and anxiety and physical pain of exhaustion could be for a moment forgotten. Thus the war became a dream, an inversion of reality’.[xiii]

Sister Edith Appleton who served at 45 CCS described long off-duty walks and other sporting activities; ‘very busy morning – two men are dying and many, many dressings to do … Our sister-in-charge does not approve of us taking part in the sisters’ egg-and-spoon race at the inter-clearing station sports on Saturday … she (old fool) thought it “unladylike”’. Later Sister Appleton notes that ‘I heard they have been shelling in St-Jans-Chappel today – so I am glad we did not take our off-duty walk there. There is a baseball match at No. 8 today, which I hope to dodge. I would rather learn lace-making than watch rounders.’[xiv] No doubt, male other ranks in medical facilities, like their colleagues in other units, played football to escape their reality in their off-duty periods. Fuller commented that ‘There was much more than just nostalgia or boredom to the soldier’s enthusiasm for football. Only thus is the avidity with which it was pursued by men weary to exhaustion explicable’.[xv] Without this escape, the players know that when the same happens tomorrow and the day after they will not be able to do their best for the incoming casualties on their shifts. Perhaps, the football is symbolic of the normality of high numbers of casualties.

The red and blue sports kit and the physically and visually co-ordinated movements of the players makes a striking comparison to the shuffling gas victims making uneasy progress towards the reception area in their motley uniforms and improvised medical dressings (Figures 7 and 8).[xvi] Virginia Woolf commented that Gassed

… pricked some nerve of protest, or perhaps of humanity. In order to emphasis his point that the soldiers wearing bandages around their eyes cannot see, and therefore claim our compassion, he makes one of them raise his leg to the level of his elbow … This little piece of over-emphasis was the final scratch of the surgeon’s knife which is said to hurt more than the whole operation.

The painting caused Woolf to leave the exhibition.[xvii] This raising of the casualty’s leg to an exaggerated height to clear the step from earthen track to duckboards about which he has been warned cruelly contrasts to the footballer athletically kicking the ball in the distance; ‘nothing could be further removed from the player’s dynamism than this halting movement.’[xviii]

The Medical Unit

When Sargent completed Gassed, his colleague at the scene, Professor Henry Tonks, remarked ‘it is a good representation of what we saw, as it gives a sense of the surrounding peace.’[xix] Sargent was unsure about a suitable title for the completed work, in a letter to an unknown recipient, he wrote:

I don’t quite agree with your objections to the title “gassed.” The place is merely a clearing station that they were brought to – the date would lead people to speculate as to what regiments were reduced to that pitiable condition, and I think their identity had better not be indicated. He concluded the word “gassed” is ugly, which is my own objection, but I don’t feel it to be melodramatic only very prosaic and matter of fact.

So Sargent did not identify the medical facility or the soldiers in the painting. He did not want to upset people by identifying the units involved. Tonks had identified the location as Le Bac-du-Sud in his letter to Yockney and initial research between 2010 and 2013 led to the provisional identification of the medical unit as being 46 CCS.[xx] The War Diaries of most of the II and III Armies’ CCSs were missing from the archives of TNA; staff believing that they had been destroyed by bombing during the Second World War. However, TNA staff discovered these diaries during a digitization project; they had been simply misfiled. The rediscovered diaries were consulted when revisiting the subject in preparation for a presentation to a Western Front Association branch; there is a yellow ‘sticky note’ on the cover of 46, 49 and 56 CCS’s War Diaries stating ‘N1451 Please put – WO 95 417.’ Perusal of all of the II and III Army CCSs Diaries revealed that none were at Bac-du-Sud at the beginning of the third Battle of Albert. The VI Corps Deputy Director of Medical Services (DDMS) notes that the German offensive of Operation Michael had forced the CCSs to be moved further back from the front line due to the danger of shelling. In March 1918 the DDMS records the VI CMDS being at Bac-du-Sud.[xxi] The 3 Field Ambulance of the Guards Division was operating the CMDS during the opening of the third Battle of Albert; CMDSs assessed and treated casualties before either sending them to CCSs or back to their units. Casualties from 46 CCS during their time at Le Bac-du-Sud were evacuated by ambulance train but motor transport was used to transport casualties from Le Bac-du-Sud between August 21 and August 23, 1918 because of the danger of shelling during the new offensive.[xxii] The men in the foreground are probably awaiting transport to a CCS. Today, a cycle/walking path follows the old railway line.

The third Battle of Albert is well documented. Zero hour was 04.55 on August 21 and, in general, the attack went well and by August 24 the CMDS at Le Bac-du-Sud was closed and moved forward.[xxiii] On August 26, 46 CCS moved back into Le Bac-du-Sud and remained there until the beginning of October.[xxiv] Therefore, Sargent sketched the VI CMDS and a century on the identity of the battalion to which the majority of the gassed soldiers belonged can be established with some certainty.

The Soldiers

At 18.30 on the opening day of the offense, the Commanding Officer (C.O.) of the CMDS at Le Bac-du-Sud phoned the DDMS to inform him that a large number of gassed cases were arriving and urgently requested twenty more motor ambulances. Sargent was there at this time. The C.O. phoned again at 19.00 requesting further transport as there were another 200 gassed cases at an ADS and on their way to the CMDS. Between 18.00 and 21.00, the CMDS received 14 officers and 106 other ranks from the 2 Division who had been gassed. By 21.00, the C.O. reported that there were 21 officers and 132 other ranks gas casualties at Le Bac-du-Sud being mostly from the 2 Division.[xxv] The stream of cases continued through the night, between 21.00 and 06.00 a further 15 officers and 254 other ranks gas cases from the 2 Division were admitted to the dressing station. But by 11.00 on August 22, the CMDS had cleared its patients onwards to CCSs assisted by 17 extra Motor Ambulance Convoy cars and three Char-à-bancs.[xxvi]

The majority of casualties at Le Bac-du-Sud were gassed soldiers of the 2 Division when Sargent made his sketches and notes. The 2 Division’s initial objective on August 21 was to capture the village of Courcelles-le-Comte.[xxvii] Their war diaries reveal that the 99 Brigade had attacked with the 23 (1 Sportsmen’s) Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers on the left, the 1 Royal Berkshires on the right and with the 1 King’s Royal Rifle Corps in reserve. The boundary between the Royal Fusiliers and the Royal Berkshires ran south of the village of Ayette, the Fusiliers proceeding to their start line directly through the village (Figure 9).

The Germans used a gas-shell barrage concentrated on Ayette early on in an effort to stem the British attack and the Royal Fusiliers moved through the gassed area as they attacked Courcelles but the gas was ineffectual due to cool temperatures and a heavy ground mist. The 99 Brigade secured Courcelles by 06:00 then moved on to their next objective. The mist began to lift after 10.00 allowing the gas to become effective in the heat of the sun; the liquefied droplets of gas vaporizing from the soldiers’ equipment and clothes, and poisoning them.

Following the initial action, the 99 Brigade commander, Brigadier-General Edmund

Figure 9. 2 Division attack plan with Courcelles-le-Comte bottom left, trench map superimposed over Google Earth image.[xxviii]

I visited the line about 2:30 p.m. and found the 1st. Royal Berkshires on the right in good order, but on the left, practically the whole of the 23rd. Royal Fusiliers were suffering from Gas. The whole valley through which they advanced was drenched with Mustard Gas, which the sun was rapidly bringing out. This Battalion was withdrawn at once but suffered some 400 gas casualties.

In future if troops have passed through a Gas-drenched area of that nature it should be a rule to get all coats off at the first halt for consolidation and either go on without or if a considerable halt is made, to expose the coats to the sun for some time.

If this had been done, a few men perhaps might have escaped. Luckily none of the Gas cases were severe and the Battalion had not a single man killed and only some 7 wounded.[xxix]

It appears Ironside was generally correct in his observations; it seems only one soldier of the 23 Royal Fusiliers died in action that day, Private Rochford, whose body has never been found or identified. He is commemorated on Panel 3 at the Vis-en-Artois cemetery. However, there are several graves of 23 Royal Fusiliers soldiers who died between August 22 and 25 in St. Hilaire Cemetery Extension, Frevent. This was used by 6 Stationary Hospital, one of the hospitals to which 46 CCS evacuated casualties; some may have died of gas poisoning. The 23 Royal Fusiliers War Diary starkly states:

Aug 20/21st. Night of. Battalion moved up for attack and assembled in front of AYETTE. All objectives reached. 14 officers and 369 men gassed.

Aug 21/22nd. Night of. Battalion moved back to position near MONCHY-AU-BOIS and reorganised into one Company.[xxx]

The 99 Infantry Brigade diary reported:

The 23rd. Royal Fusiliers had passed through very heavy gas when moving up to the attack, and, as the heat of the day increased, it’s effects became manifest and eventually 13 officers and 346 Other Ranks had to be passed out of the line as Gas casualties, though there were very few severe cases…Remnants of the 23rd. Royal Fusiliers were to go right back to the old Reserve Battalion location in the O.G. Position near MONCHY AU BOIS.[xxxi]

Other units were affected by the gas but not in such significant numbers. The 8 Infantry Brigade Headquarters’ estimated that over 1000 mustard gas shells fell between 02:00 and 03:15 on August 21 betwixt their headquarters in a quarry north of Ayette and Ayette itself. Their 1 Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers followed the 23 Royal Fusiliers but moved forward from an assembly point just south of Ayette rather than moving through the village. By the end of the day, the Royal Scota Fusiliers had suffered 343 casualties (‘38 other ranks killed, 254 other ranks wounded, 19 missing, officers = 1killed, 6 wounded, 2 missing’) of which only 31 were gassed.[xxxii]

The identification of the soldiers as being from the 23 Royal Fusiliers is supported by the 99 Brigade pre-attack administrative instructions that casualties would be evacuated from the regimental aid posts to ADSs at Monchy or Ransart and then by car to the CMDS at Le Bac-du-Sud.[xxxiii]

Gassed – the wounded to fit and clean

The artist Paul Gough, in agreement with Malvern, concludes that Gassed is ‘a testament to the pity of war, but also an elegy to redemption and recovery.’ He finds fault in that the ‘painting only captures an air of discomfort but not the full gamut of pain’ that mustard gas inflicted … the bandages are too ‘clean, the wounds discreet, even polite; the statuesque Tommies are fit, whole and cared for’.[xxxiv] The novelist E.M. Forster, in his ironic essay ‘Me, them and you’ complains that the picture is too clean, painted for the upper classes who ‘only allow the lower classes to appear in art on condition that they wash themselves and have classical features … A line of golden haired Apollos moving along a duck-board … no one complained, no one looked lousy’.[xxxv] However, it is known that 23 Royal Fusiliers did not suffer many gunshot or shell fragmentary victims at this stage of the battle and this battalion was known as ‘The Sportsmen’ because they recruited sportsmen from civilian life, so perhaps they were fitter and more statuesque than the average soldier. As Sargent had taken his notes and completed his sketches in the early evening, many of these soldiers were in the early stages of gas poisoning and had had initial treatment at Dressing Stations and ADSs before arriving at Le Bac-du-Sud.

The 23 Royal Fusiliers had worn their gas masks for three hours in the heavy gas environment of Ayette when their clothes and kit would have become soaked in gas droplets. As they advanced from Ayette out of the visible gas they removed their masks and as the sun appeared it evaporated the gas from their clothes and slowly poisoned them. The slow but insidious action of Mustard Gas was shown by an incident on 12 March 1918 when one NCO and five other drivers of 16 Motor Ambulance Convoy were hospitalized with gas poisoning after driving gas casualties from the Main Dressing Station to 56 CCS. One driver, Pte A. Edwards, was awarded the Military Medal for insisting on continuing the job until he reached Albert despite his exhaustion.[xxxvi]

Figure 10. John Singer Sargent, Gassed.

Sargent does illustrate the early symptoms of being gassed and some men would have been more severely affected than others. The seventh soldiers in both lines turn to vomit, hence avoiding their colleagues in front but not their unseen comrades sitting and lying alongside. Sargent has the nearest turning away from the viewer preserving some dignity. In the foreground, one soldier alleviates his nausea by sitting up, another eases his burnt throat by drinking from his water bottle. By the time Sargent began his painting back in London, he knew from his own stay in a CCS what was to come for his subjects and this may have influenced his interpretation of the scene; their pain is still going to increase despite being at the CMDS. Medical orderlies at the CMDS would have recognised the early symptoms of mustard gas poisoning and evacuated them to CCSs. Mild cases were hospitalised for a few days before being returned to duty and severe cases sent on to the Base hospitals from CCSs.

The calmness Sargent experienced in the midst of the suffering during his hospitalization at 41 CCS is brought out by the muted tones, the stillness of the soldiers in the foreground awaiting transport and the succession of vertical lines of the slow moving figures. The completed work led his colleague at the scene, Professor Henry Tonks, to remark ‘it is a good representation of what we saw, as it gives a sense of the surrounding peace.’[xxxvii]

The overall impression given by the soldiers in the photograph of 55 Division gas casualties (Figure 6) and in Sargent’s painting is of resignation and endurance. For some, the soldiers’ blindness may be a metaphor for the destruction they have seen and which the civilian cannot imagine; they are resigned to man’s inhumanity to man and have endured it. This technological war was redefining the Victorian masculine ideal of stiff upper lip, self-control, restraint and will-power. Some have argued that the notion of endurance as a masculine trait was actually the product of this war, an apt descriptor for the qualities required in the trenches. Meyer opined that ‘men who endured were those who controlled their emotions not only in the moment of fear and stress but also when confronted with the on-going horrors of warfare’.[xxxviii]

In 1919, Winston Churchill, responding to the toast to ‘His Majesty’s Ministers’ at the Summer Exhibition banquet, thought that the end of the war would set free the spirit of the age in art, would liberate the ‘cultured forces which were nourished in the bosom of our country … the field had been harrowed, terribly harrowed! They had only to look at that tragic canvas (Gassed) with all its brilliant genius and painful significance, to see how the field of national psychology must have been harrowed by the events which had taken place in this war’.[xxxix]

Charteris thought Sargent illustrated ‘much of the moral quality of those taking part’ in the war; qualities Ironside referred to when he wrote ‘great credit is due to the men of the 23rd Royal Fusiliers who, although many must have been suffering from Gas before starting, went straight through to their objectives without faltering.’[xl]

Conclusion

The media utilises Gassed frequently around Remembrance Day and it is a representational form constructing and reconstructing collective memory, a form shaping ‘our links to the past, and the ways we remember, defining us in the present’.[xli] Charteris, Sargent’s biographer, regarded his youthful drawings as precocious, ‘not in imagination, but as literal records of what was immediately before him’, done for the sheer fun of translating what he saw onto paper. Charteris emphasizes that Sargent tried to reproduce ‘precisely whatever met his vision without the slightest previous “arrangement” of detail, the painter’s business being, not to pick and choose, but to render the effect before him, whatever it may be.’[xlii] However as a representational artist, Sargent produced images of what he observed, but as he was not a realist he has added his interpretations to achieve the effect the event had on him.

There is no evidence of him playing football or even watching football growing up as an American in an American family in Europe and the social circles he frequented were unlikely to contain football enthusiasts. He was a keen swimmer and lawn tennis player, and an enthusiastic, if rather unskilled huntsman keeping a horse and riding with the Heythrop, the Warwickshire, and the North Cotswold Hounds. However, it is highly probable that in his short three month stay in France he had frequently observed British soldiers playing football in nearly all circumstances except for when under direct fire.

Gassed was an unplanned commercial success between the wars appearing in advertisements and as prints available to the public both as a tribute to the endurance of the fighting man and as anti-war propaganda.[xliii] Brandon believes that war art needs to be examined in the context of its creation and the meanings it has gained over time; this requires input from both the artist and the viewer, a painting is time-specific, cultural specific and evolving. She considers it appropriate that the meaning a viewer derives from a specific work is as much about their own reaction to it as about the work itself and as anti-war protestors respond to works showing the futility of war, they rate Gassed, addressing the futility and horror of war, highly.[xliv] Hynes argued that World War I was an imaginative event as well as a military and political event, fundamentally altering the way in which people thought about the world, in essence changing reality. One significant change was in the cast of characters in war, the military hero was no longer centre stage on his own, he was now challenged by the disfigured, the coward, the frightened boy, the haunted veteran and the shell shock victim. In the Channel 4 production The Genius of British Art, Jon Snow said that ‘artists were the first to challenge the historical view that war was all about victory and glory’.[xlv] Gassed portrays the effects of a new terrible weapon and evokes compassion and probably has had the most effect on British cultural memory of any piece of World War I art.

The choice of Sargent, the foremost society portraitist of the Edwardian gilded age, as a war artist seemed, on the surface, strange. However out of ‘super-sized’ paintings commissioned for the proposed Hall of Remembrance, only Sargent’s Gassed was completed. It was voted the 1919 picture of the year by the Royal Academy of Arts, although some reviewers felt it was too heroic and failed to sufficiently emphasize the obscenity of war. To many viewers the attractive but deceptive gilding light marks the soldiers as the sons of the salon society Sargent portrayed. With stoical dignity they walk towards the absolution that their courage and sacrifice merit, simultaneously indicating the sunset of a society that allows the immolation of its youth on a grand scale.

When considering the interpretations of Gassed, it is worth deliberating upon the opinions of two of his friends; his biographer Charteris opined ‘I feel certain that his conscious endeavour, his self-formulated program, was to paint whatever he saw with absolute and researchful fidelity, never avoiding ugliness nor seeking after beauty.’ In her afterword to Charteris’s biography of Sargent, Violet Paget, writing under her pseudonym Vernon Lee, concludes that Sargent was not an imaginative painter; he did not build up allegories or narrate events.[xlvi]

His symbolism was imminent in the aspects which he painted. Who else has ever expressed the tragedy of war as he has done in his group of gassed soldiers, it’s horror conveyed without contortion or grimace; and war’s tragedy assigned a subordinate and transitory place in the order of things by that peaceful landscape and the game of football in the middle distance. This composition is as majestically serene as some antique frieze; while for the emotions of the beholder it is terrible, like a chapter of Tolstoi.[xlvii]

Charteris recorded that Sargent was noted for being able to say exactly what he had to say by indication and description; ‘his object was to record with the utmost skill attainable the thing as he saw it, without troubling about its ethical significance or, indeed, any significance other than its visual value.’ Sargent recognised that he was a representational painter and remarked to one sitter ‘I do not judge, I only chronicle’.[xlviii] He recorded the suffering of the casualties as he located football as a centrality within the discourse of everyday life of a main dressing station. Therefore, it is probable that Sargent actually witnessed football being played at Le-Bac-du-Sud; Tonks commented on him omitting the children but did not mention adding football. However, whether it was a ‘proper’ match as shown or simply a kick about that Sargent elevated through interpreting his notes, or to underline the omnipresence of the game in the army is unanswerable.

In 2010 Alastair Sooke stated that art conveys the feelings of war far more than the photographic record and Cork considers that Gassed is an effective icon of the anti-war movement as well as one of the great monuments of World War I.[xlix]

To conclude, although thousands of pages have been written examining Gassed for meanings, metaphors, allegories, and symbols; Sargent painted what he saw, although this was painted months after he visited the CMDS and was completed with reference to his notes and sketches from the day. Therefore, it is highly probable that the main components of the painting are what he saw, trains of blind men being led to a triage centre, lines of men waiting to be evacuated to the next stage of the evacuation trail, off-duty medical personnel playing football by their camp, the distant battlefield and the rising full moon. His preliminary sketches show that he was seeking to complete the work in a manner of the atmosphere he noted and remembered. The viewer of Gassed in the IWM London’s Blavatnik Galleries is confronted by an elegiac peacefulness, the thin paint surface and the sketch-like surface texture points to a free and expressive painting which encourages the viewer to image this is a real scene.[l] The original viewers in the early twentieth century may have felt they were eye witnessing a contemporary event revealing the effects of modern technological war. To many the Sargent Room, where it was previously displayed, was a ‘dark experience’, ‘bridging the existential gap between the here-and-now of the tourist and the event’ of over a century ago, creating empathy and live memory.[li] Although the artist places the viewer in the same space as the soldiers through his composition of the foreground, the soldiers do not look out inviting the viewers, to share their predicament; the viewers remain in the stands.

Article copyright of Iain Adams

References to Part 2

[i] ‘The Royal Academy: A First Notice’, The Times.

[ii] Kilmurray and Ormond, Sargent, 264; Harris, ‘Gassed’, 16; Roger Tolson, ‘Gassed’, Art from Different Fronts of World War One, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/trail/wars_conflict/art/art_frontline_gal_01.shtml.

[iii] Brandon, Art and War, 6.

[iv] Tolson, ‘Gassed’.

[v] John Terraine, General Jack’s Diary (London: Cassell, 2000), 91.

[vi] F. Clive Grimwade, The War History of the 4th Battalion, the London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers), 1914-1919 (London: Headquarters of the 4th London Regiment, 1922), 293.

[vii] House of Commons Debate, 14 March 1916, vol. 80, cc.1985-2046; Army Estimates, 1916-1917: Disabled Soldiers (Pensions) [Mr. Pringle], 2041.

[viii]Instructions for the Training of Platoons for Offensive Action, February 1917 ed., General Sir Ivor Maxse papers, 69/53/15 File 53, IWM.

[ix] Terraine, General Jack’s Diary, 226-227.

[x] James Roberts, 2006. ‘“The Best Football Team, The Best Platoon’’: The role of football in the proletarianization of the British Expeditionary Force, 1914-1918’, Sport in History 26 No. 1 (2006): 26-46.

[xi]Tonks to Yockney.

[xii] War Diary, ‘19 Casualty Clearing Station’ (CCS), TNA, WO 95/414.

[xiii] Wade Davis, Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory and the Conquest of Everest (London: The Bodley Head, 2011), 18, 19, 21.

[xiv] Ruth Cowen, ed., A Nurse at the Front: The First World War Diaries of Sister Edith Appleton (London: Simon & Schuster, 2012), 46-47, 49.

[xv] John G. Fuller, Troop Morale and Popular Culture in the British and Dominion Armies, 1914–1918 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), 94.

[xvi] IWM. Art from the First World War (London: IWM, 2008).

[xvii] Virginia Woolf, ‘The Royal Academy’ Athenaeum, August 22, 1919, 92-93.

[xviii] Cork, A Bitter Truth, 221.

[xix] Charteris, John Sargent, 212

[xx] Charteris, John Sargent, Section of a letter, recipient not indicated (Charteris?), 215; Tonks to Yockney; Iain Adams and John Hughson, ‘The First Ever Anti-Football Painting? A consideration of the soccer match in John Singer Sargent’s Gassed’, Soccer and Society 14 no. 4 (2013).

[xxi] War Diary, ‘DDMS’.

[xxii] War Diary, ‘No. 5 Field Ambulance’, TNA, WO-95-1337-5.

[xxiii] War Diary, ‘DDMS’; War Diary, ‘No. 5 Field Ambulance’.

[xxiv] War Diary, ‘H.Q Third Army General Staff. Director of Medical Services’, TNA, WO95/382/1; War Diary, ‘16 Motor Ambulance Convoy – 569 Company Army service Corps’, TNA, WO95/ 410/7; War Diary, ‘No. 6 Motor Ambulance Convoy’, TNA, WO 95/410/2; War Diary ‘3 Army Troops 46 C.C.S.’, TNA, WO 95/417/1_2 (1).

[xxv] War Diary, ‘DDMS’.

[xxvi] War Diary, ‘No. 3 Field Ambulance’, TNS, WO 95/1207/1_3.

[xxvii] War Diary, ‘General Staff Third Army’, TNA, WO95/372-1.

[xxviii] Plan from Everard Wyrall, The History of the Second Division, 1916-1918 (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1922).

[xxix] War Diary, ‘2 Div., 99 Infantry Brigade: Headquarters – Infantry Brigade No. G.A. 3: Operations against MOYBLAIN TRENCH’, August 21, 1918

[xxx]War Diary, ‘2 Div., ‘99 Brigade: 23 Battalion Royal Fusiliers’, TNA, WO 95/1372.

[xxxi] War Diary, ‘2 Div., ‘99 Infantry Brigade: Headquarters’, August 21, 1918.

[xxxii] War Diary, ‘3 Div., 8 Infantry Brigade: Headquarters’, TNA, WO 95/1419/5.

[xxxiii] War Diary, ‘2 Div., 99 Infantry Brigade: Headquarters, Infantry Brigade Administrative Instructions Order No. 251 Appendix 24’, August 21, 1918.

[xxxiv] Gough, A Terrible Beauty, 200.

[xxxv] Edward Morgan Forster, ‘Me, Them and You’, in Abinger Harvest (London: Edward Arnold, 1936), 38-39.

[xxxvi] Historical Record of No. 16 Motor Ambulance Convoy – 569 Company Army Service Corps, TNA, WO 95/410/7.

[xxxvii] Charteris, John Sargent, 212

[xxxviii]George L. Mosse, Image of Man: The creation of modern masculinity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996); Jessica Meyer, Men of War: Masculinity and the First World War in Britain (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2009), 142.

[xxxix]The Times, May 5, 1919, col. D.

[xl] Charteris, John Sargent, 215; War Diary, ‘99 Infantry Brigade No. G.A. 3: Operations against MOYBLAIN TRENCH’.

[xli]James E. Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust, Memorials and Meaning (New Haven: Yale University 1994), 9.

[xlii] Charteris, John Sargent, 13, 77.

[xliii] Merion and Susie Harries, The War Artists: British Official War Art of the Twentieth Century (London: Michael Joseph, 1983), 99.

[xliv] Brandon, Art and War.

[xlv]Samuel Hynes, A War Imagined: The First World War and English Culture (Oxford: Macmillan, 1990); Jon Snow, presenter, The Genius of British Art: The Art of War. Aired November 7, 2010, Channel 4.

[xlvi] Charteris, John Sargent, 251; Vernon Lee, ‘J.S.S.: In Memoriam’ afterword to John Sargent by Evan Charteris (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1927), 235–55.

[xlvii] Lee, ‘In Memoriam’, 254

[xlviii] Charteris, John Sargent, 71, 107.

[xlix] Alastair Sooke, presenter, The Art of World War II: A Culture Show Special. Directed by Bill MacLeod. Aired September 13, 2010, BBC2; Cork, A Bitter Truth.

[l]Kilmurray and Ormond, Sargent.

[li]William F.S. Miles, ‘Auschwitz: Museum Interpretation and Darker Tourism’, Annals of Tourism Research 29 No. 4 (2002), 1176.