Many different people wrote the scripts for Manchester’s pantomimes in the Victorian era, some well known in theatre history and the majority long forgotten. In this two part article we will focus on three typical authors who wrote the librettos of productions that were competing for audiences in the three main theatres in central Manchester during the pantomime season 1886-1887 through the first reviews of each production as they appeared in the Manchester Guardian.

Background

What separates pantomime from other theatrical genres is that it is in a constant state of reinvention. Each year’s productions function as a comedic snapshot of the current state of the cultural and social life of its audience. Very few copies of the manuscripts of those pantomimes have survived, partly it seems because as each theatre would create a new pantomime each year, with new jokes to mirror what was current news. Pantomime was not regarded as a serious theatrical genre, and consequently the future value of the ‘book’ was not recognised.

The local and topical references were of greater importance in Victorian productions than is usually seen in their twenty-first century descendants. Until the end of the century, much of the content was written locally for an independently owned theatre. While the Victorian pantomimes have value for twenty-first century researchers studying social history and leisure practices, it is easy to understand why they were regarded as a disposable part of everyday life.

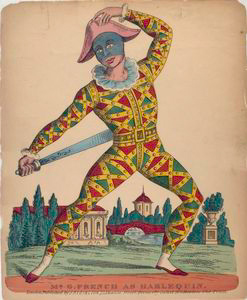

- Harlequin with his slapstick

At the beginning of the nineteenth century pantomime consisted of a short opening scene, usually in a familiar local setting. This was rapidly followed by a magical transformation, effected by Harlequin with his magic wand, the original slapstick, into the scene of an otherworld, where the characters of the opening were transformed into the stock characters of the harlequinade. There was music, dancing, bawdy physical comedy, and biting satirical humour which was often political in nature. The freedom to create the work was constrained by the draconian laws governing what could be presented on stage. The Theatre licensing Act of 1737, during the reign of George II, was designed to control what was said about the Government in British theatres, a symbol of middle-class fears of revolution. One measure it introduced, meant that only in theatres awarded the royal patent was it permitted for the spoken word to be presented on the stage. Manchester was awarded a patent for its first Theatre Royal in 1775.

As fears of revolution declined, the 1843 Theatre’s Act permitted much greater freedom on the stage, triggering a wave of speculative theatre building to meet the increased demand of potential theatre audiences. Manchester’s Theatre Royal had been joined by the Queen’s Theatre in 1830. The Princes Theatre followed in 1864 and by 1884 there were six legitimate theatres in the city centre with many more on the outskirts of the city and in its satellite towns. Licensed theatres still had to submit the manuscripts of plays to the Lord Chamberlain’s Office until 1968. These events influenced how pantomimes were written and who wrote them.

Aided by new developments in theatre technology, the increased freedom to speak on stage saw a further evolution in the form of pantomimes. In the spectacular form of high Victorian pantomime, the opening scene grew to became the main part of the entertainment and the harlequinade gradually reduced until it became a ten-minute knockabout clowning routine added to the end of the pantomime, largely targeted to amuse the children. Eventually, by the turn of the twentieth century, it was allowed to fade away altogether.

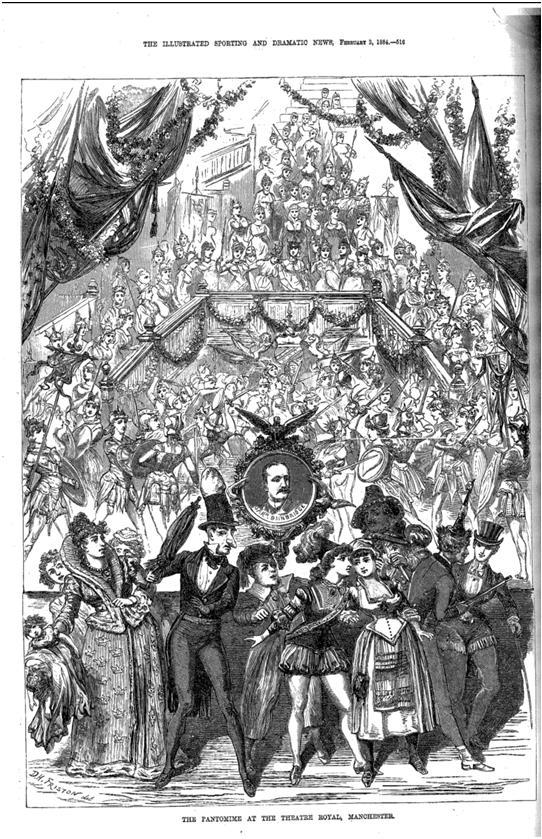

- Theatre Royal, Manchester. Babes in the Wood, 1883-1884, The Illustrated and Sporting News, 3 February 1884

By the 1880s, a new business model was appearing in theatres, with the independently owned theatres being bought up by syndicates of investors and becoming ever larger concerns. This allowed owners that were remote from the communities the theatre served to make economies of scale in their financial management. Due to the high expense of producing spectacular pantomime and vast amounts of time required to bring them to the stage, managements were looking to be more efficient in their production. This often meant buying or hiring in productions, props and costumes that had been previously presented elsewhere, which gradually diluted the potential for a script with local and topical references.

Manchester in 1886, remained largely independent with each theatre producing its own pantomime and the manager’s competing to be regarded as having the best pantomime each year. At least some of Manchester’s theatres retained the practice of hiring authors to devise the annual pantomime.

Anarchy with the script

The librettos, as written by the authors, were reproduced in Pantomime ‘books of words,’ which were sold as souvenir programmes to theatre audiences. However, a feature of the early pantomimes was that, during their run in the theatre, the performers, especially those playing comic characters, would take liberties with the author’s words, adlibbing and introducing their own ‘business’, the industry term for physical comedy. A successful pantomime could run from Christmas to Easter. A major feature of the pantomime was its topicality, and during a long run it was common practice to make changes to the libretto to keep the jokes current and to develop the business. There is evidence of this in collections of surviving pantomime books, where there may be several copies for a particular production, numbered as different ‘editions.’

Once the 1943 Theatres Act came onto the statute books and the spoken word was permitted on the stage, this created a greater demand for writers. There were two different areas that the majority of authors came from. One group came from the theatrical community itself as performers or former performers, the others mostly had a journalism background, moonlighting to have some fun and bringing themselves some additional income. Little credit was given to the authors of pantomimes, nor were they well paid.

William Wade

- William Wade

William Wade was born in Manchester in 1857 and by the late 1880s was the Deputy Editor of the Manchester Times. His first Manchester pantomime was performed at The Prince’s Theatre in 1886 when he was 29 years old. The subject was Robinson Crusoe, a popular topic for pantomime at the time. The first review of Manchester Guardian, (it was usual for newspapers to visit the pantomimes again later in the run to see how the productions had developed from the first night), had this to say about the manuscript:

Mr William Wade, who has written the book and designed the dresses for “Robinson Crusoe,” may be congratulated on his success. Not that his book is a masterpiece of wit, overflowing with clever puns or vigorous lines – though that part of his work is good enough, – but the model and plan of the whole, a much more important matter, has been thoughtfully considered, with a good result.[1]

Although the use of puns may make a twenty-first century audience wince at its crassness, it was the height of fashion in Victorian comedy, for the audience to laugh along with or groan at as they wished. It was an expected feature in pantomime and often highlighted in italics, capital letters or bold in the books of words, to hammer home the wit, in case the reader had missed it. After detailing at length, the scenes that make up the story and reviewing its music, scenery, costumes and some of the performances of its stars the reviewer concluded:

Mr. Smyth has produced a pantomime very superior in tone to many we have seen of late years. The absence of stupid political allusions, and, speaking generally, the subordination of the music hall element are things greatly to be commended. And this, with the presence of an actor such as Mr Shine and an artist of the peculiar charm of Cinquevalli, should ensure “Robinson Crusoe” a long run and make it an altogether exceptional success.[2],[3]

- The Prince’s Theatre, Manchester

An admirable start for Wade and praise that the production focuses on remaining faithful to the original story, at least to the pantomime version of Daniel Defoe’s story where a vast number of characters and dancing girls proceed by ship to rescue Crusoe from his lonely desert island, with Shine in the dame role of Widow Crusoe, mother of the hero. By 1886, the increased use of music hall artistes in pantomime was a cause for much debate around notions of respectability and complaints from regular pantomime performers about influx of music hall stars taking work away from them.

In seems likely that the Manchester Guardian sent the same reviewer to see the pantomimes at the Theatre Royal and the Queen’s Theatre, as these reviews flag up the same pet concerns as highlighted in the Prince’s Theatre above. Part 2 examines those reviews and the judgement of the manuscripts authored by Thomas F. Doyle and E F Fay respectively.

Article © Claire Robinson

Read Part 2 click HERE

[1] Manchester Guardian, 28 December 1886. p.8

[2] Ibid.

[3] Mr Smyth is J C Smith, theatre manager at the Prince’s Theatre in 1886. Mr Shine is J L Shine a well-known comic actor. Cinquevalli is Paul Cinquevalli famous as an excellent juggler, very popular in Manchester.