The author would like to express his special thanks to Professor John Haldane, Anne Martin and Paul Du Noyer

As shown by a previous Playing Pasts’ article about GFC discoveries [Click HERE to read the article] the importance of old photographs in the historical reconstruction of early women’s football in Italy should not be underestimated. Studying them carefully, a lot of historical data can be seen and then analysed .

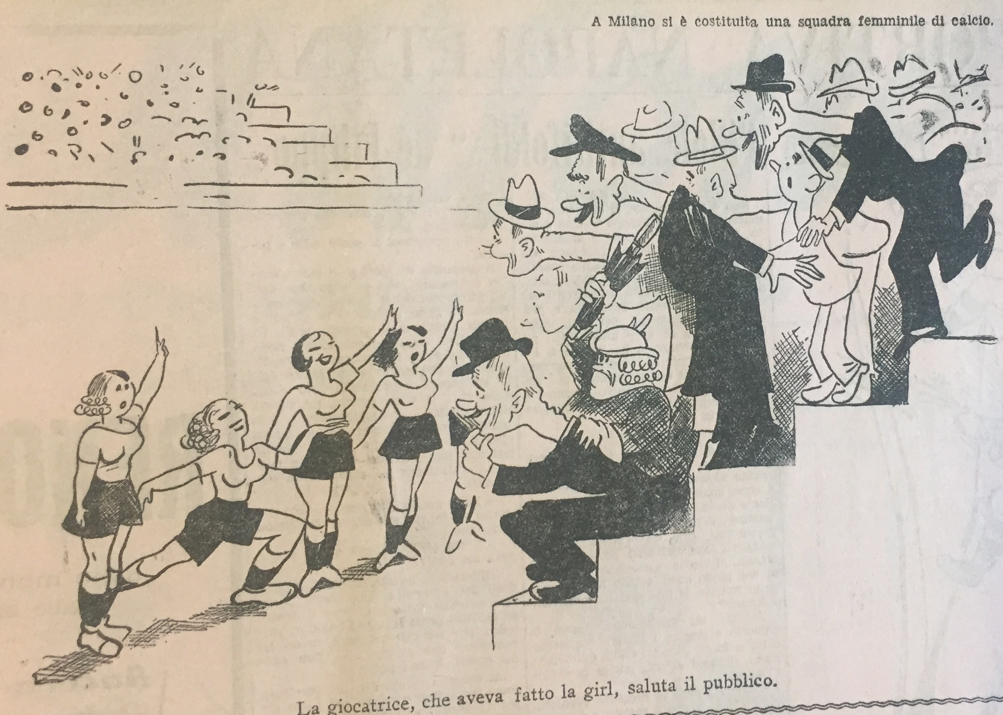

In this article, two beautiful 1931 photos cast some light on a pseudo-sports activity we could call ‘vaudeville women’s football’, played between the 1920s and the 1930s in Italy by girls: which was the English word Italians at that time used to define the chorus girls engaged in riviste di varietà ‘revue shows’.

These kind of football matches were useful not only to publicize the upcoming dancers’ shows in town but also to raise some additional funds. As female entertainers, their sports activity during breaks in their tours was socially accepted: they were not ordinary girls, and these games were played in jest, not seriously. For the same reason, they were allowed to wear, without any hint of scandal, the same sports shorts that were a source of controversy in the Italian conservative press of the day when wore by Italian athletes. Since it was clear that they were not sportswomen but showgirls, there was no restriction about the male audience, as would subsequently happen with the 1933 Milanese calciatrici: instead, male audiences flocked to the football field in order to watch these vaudeville sporting shows … and to admire the girls’ legs!

When they founded the first women’s football team in Italy, the GFC player had to fight against some Italian journalists, who tended to depict them as chorus girls, as Rome-based sports magazine Il Tifone [whose journalists had not had a chance to watch the Milanese playing on the field].

The caption says: “A women’s football team was founded, in Milan. The player, who was a chorus girl, greets the audience”

Source: Il Tifone, 28/02/1933, p. 7.

On Tuesday 27 January 1931, Naples-based sports weekly magazine La Voce Sportiva [which supported women’s sports during those years] wrote that two days later a football match between a female and a male team was scheduled, adding jokingly that ‘we’ll bet that such a perfect ‘passing’ game has never been seen’. In the next issue [Tuesday 3 February 1931] no news about the ‘mixed’ football match can be found. Nevertheless, something actually happened in Naples, on Thursday 29 January 1931 …

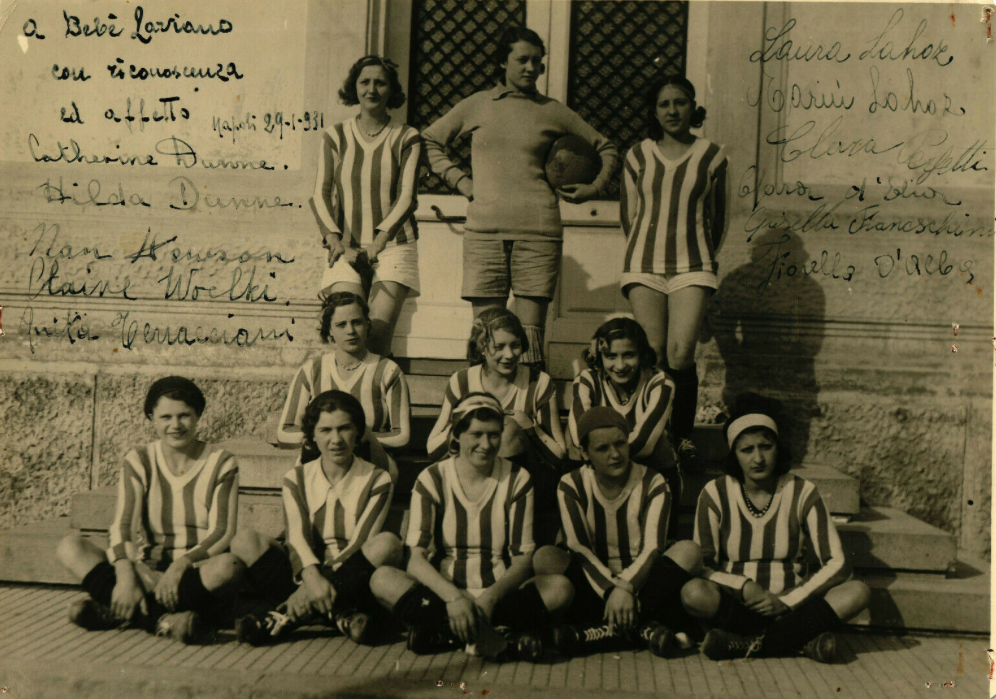

Handwritten caption says:

‘A Bebè Laviano con riconoscenza ed affetto ‘To Bebè Laviano, with gratefulness and love’

Napoli 29-1-931 ‘Naples, 29 January 1931 – Catherine Dunne, Hilda Dunne, Nan Hewson, Claire Woelki, Anita (Anika?) Terracciani’

On the right: Laura Lahoz, Mariù Lahoz, Clara Perfetti, Clara d’Elia, Gisella Franceschini, Fiorella D’Alb[a]

According to John Haldane, 1) Hilda Dunne is the woman seated second from the left in the front row, with her legs and arms crossed, with the white collar;

2) her sister Catherine is the girl seated to the right in the middle row on the steps.

It can then be can deduced that the list order isn’t in fact the photograph order, which was probably just the signing order, as suggested by the fact that the Dunne and Lahoz sisters signed it one after the other.

John Haldane remembers that Nan Hewson was ‘a good friend of my mother at the time. She may be one of those seated to her left or right’ in the first photo. This friendship could explain why Nan signature comes after the Dunne sisters.

Source: http://bit.ly/3aUtSro

Female and male players before (or after) the match

According to John Haldane, 1) Hilda Dunne is standing third from the left in the second row, with the white collar; 2) her sister Catherine fifth from the right.

Please note that Scandone writes that the girls on that day wore maglietta e mutandine sportive. The first term still means ‘football jersey’ in contemporary Italian language; the second nowadays means ‘slip’, but watching this picture it can be deduced that in 1931 it meant ‘sports shorts’.

Source: http://bit.ly/37FzZhj

On that Thursday, a female team composed of 11 chorus girls from the Teatro Nuovo dancing company played against a male AC (now SSC) Napoli supporters team, winning 5 – 3. All the girls’ team goals were scored by the high-spirited center-half.

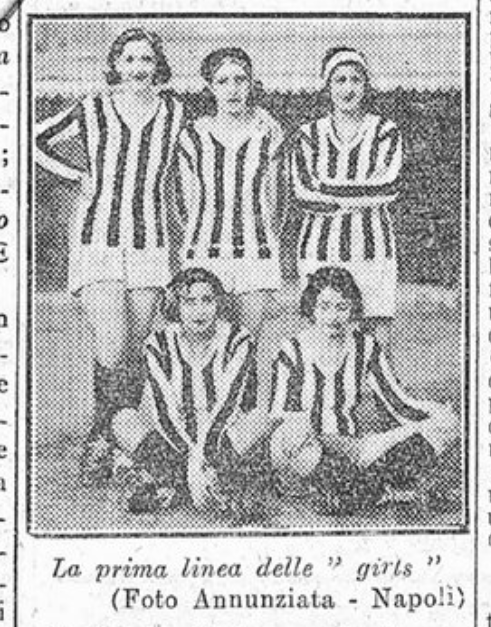

Italian caption says: ‘Chorus girls’ first line’, meaning the attacking line: at that time, football teams (including the GFC two years later in Milan) used to play the 2-3-5 system.

Source: Il Littoriale, 3 February 1933, p. 3

Italian caption says: ‘Two teams before the match: Salvietti’s chorus girls’ team and Giorgio Ascarelli team’. Agostino Salvietti (1882-1967) was leading a theatre company in Naples and was himself one of the greatest actors in town, and he was going to be involved with many of Totò movies.

Giorgio Ascarelli (1894-1930) had been the owner of a textile mill and the previous AC Napoli President. Male players are alsoAscarelli textile mill workers, who were AC Napoli supporters as well.

Source: Il Littoriale, 3 February 1933, p. 3.

Il Littoriale‘s journalist Felice Scandone reported that the huge audience included William Garbutt, the AC Napoli [male] team coach. Pointedly, Scandone calls him ‘Mister Garbutt’, nowadays in Italy boys still refer to their football coach as mister, as a result of the influence of this former Blackburn Rovers player, who was considered the model of a professional manager in early 20th century Italy. When he reached Genoa in 1912 this newcomer from England was called “Mister Garbutt” later, this became the nickname of the Genoa coach, who led the team to win three Italian scudetto titles (1914-1915, 1922-1923 and 1923-1924).

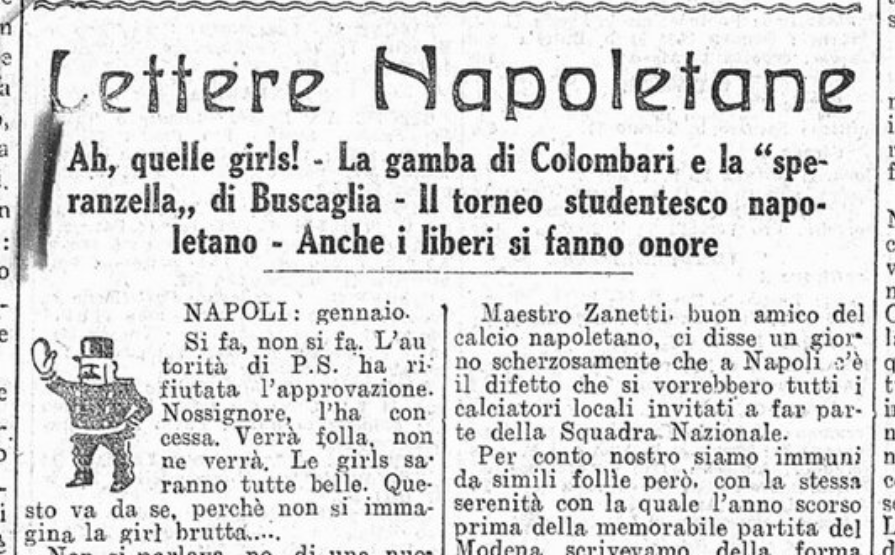

The title of the Il Littoriale article about the match.

Please note the policeman pictured at the beginning of the article, journalist Felice Scandone writes that just before the match organizers were uncertain whether the police would give authorization for such a public sports event.

Source: Il Littoriale, 3 February 1933, p. 3

William Garbutt as Napoli trainer, season 1929/1930

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Napoli_1929-30.png

What about the female players? – The Lahoz sisters came from a family of actors, who used to tour in Italy and America in the first decades of the 20th century; indeed, after World War 2, Clara D’Elia was later to appear with the great Neapolitan actor Eduardo De Filippo. However, the two most interesting players are the centre-half and midfield sisters, Catherine and Hilda Dunne.

Reading Paul Du Noyer’s book about the Liverpool-based new wave band Deaf School [Deaf School. The Non-Stop Pop Art Punk Rock Party, Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2013], I discovered that the mother of vocalist Anne Martin [aka Bette Bright], Christina Dunne, was a tap dancer with her two [older] sisters. They were called the Catherine Dunne Trio (p. 53). As Anne told Du Noyer:

‘they were quite crazy, some of the stories they told. They worked in Paris quite a bit and they’d get all their food on a tab at this Russian bistro, and get all their clothes made, they’d have their eyelashes made from their hair. But they’d have no money so they’d settle up when they could. She would do Russian dancing, on roller skates, on a pitched stage. Imagine!’ [pp. 53-54].

According to Anne, her mother:

‘was a real character’, and ‘quite unusual’ for those times, ‘because she had my sister and me when she was in her 40s. So she’s had a whole life’[p. 54].

After writing an e-mail to Du Noyer, in February 2020 I was able to get in touch with Anne Martin, who confirmed that:

‘my mother Christina and her sisters Hilda and Catherine were all dancing independently and then together as a trio in Italy’.

Anne then put me in touch with her cousin John Haldane, son of Hilda Dunne [later Haldane], and an academic philosopher – he is Moral Philosophy Professor at University of St Andrews, Scotland and Baylor University, Texas. Answering my email, he wrote an accurate account his mother and aunts’ history:

Hilda and Catherine were two of five children: four girls and a boy John. Hilda [born 1910] was the eldest, with Catherine [born 1912] second, then twins Christina and Maureen. All four girls went into theatre and dance. At the time of the photograph Hilda and Catherine were travelling together but later Catherine joined the twins in a dance group she led called ‘The Catherine Dunne Trio’. While the some of the sisters including my mother and Catherine sometimes worked together, the Catherine Dunne Trio was Catherine, Christina and her twin Maureen.

In the 30s Hilda and Catherine [their nicknames for one another were ‘Yalse’ and ‘Taff’] were in various shows at the Teatro Nuovo and Teatro di San Carlo [they lived nearby in the Quartieri Spagnoli district] and got to meet many people in Naples Society including Francesco Caravita Principe di Sirignano [known familiarly as ‘Pupetto’] and Eduardo Di Filippo. Hilda also worked at the Teatro di San Carlo serving as ballet mistress and dance choreographer. She also knew I have a review in Scotland of a production of a show titled Tutto va bene quando va bene [‘All goes well when it goes well’] in which the reviewer praises my mother for her performance and direction. She also knew the actor and songwriter Odoardo Spadaro.

At the time of the photograph [1931] Hilda was 21 and Catherine 19. They travelled in France and North Africa as well as in Italy but at some point Catherine moved to Milan while my mother remained in Naples.

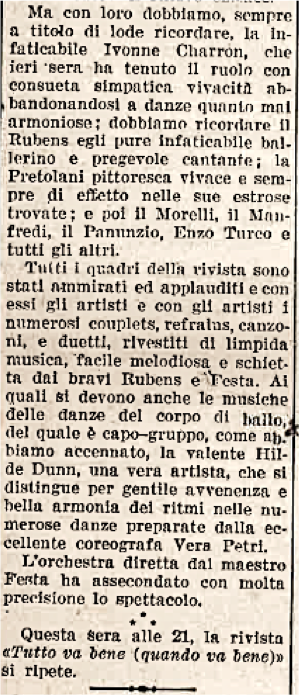

The above clipping is about Tutto va bene [quando va bene] ‘All Goes Well [When it goes well]’ show, at Teatro della Fiera, Naples [courtesy of John Haldane]. The clipping is undated, but historical sources say that actress Tina Pica [who used to act with Totò] was engaged with Tutto va bene (quando va bene) in 1937. The newspaper reports that the female dancers, called Balletto Scandall, were ‘headed by the talented and superb Hilda Dunn’, who is praised as ‘a true artist who distinguishes herself by the gentle harmonious and rhythmic execution of her numerous dance sequences, as choreographed by Vera Petri’ (translation by John Haldane).

In his 1931 article, Scandone writes that Garbutt liked the arte calcistica ‘football ability’ of the two high-spirited dancers ]one a centre forward, the a other halfback], ‘who succeeded in fully rehabilitating the infamous Irish soccer’, leading the girls’ team to a 5-3 victory. John Haldane confirms the Irish roots of the Dunne family:

The Dunne family had emigrated to England from Ireland in the early 1920s following the ‘Irish War of Independence’ that led to the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922. Although a Catholic family, the father Edward had been in the Royal Navy and then served as HM Coast Guard officer near Kinsale in the South of Ireland and was loyal to the Crown.

Following two IRA attacks on the coastguard station in 1920, Edward Dunne judged that is was unsafe for him and his family to remain and so was given a posting in England – in Whitstable as Customs Officer for the north coast of Kent. It was there that the girls grew up and at an early age began to take an interest in dance and theatre.

When Italy entered the war with Germany against the Allies, everything changed for Englishwomen Catherine and Hilda:

Catherine was also arrested but having been born in Ireland she was able to claim neutrality and was set free to return home. My mother [Hilda] was more committed to the British side of her identity and did not invoke Irish citizenship. This led to a period of four year internment in various places including the convent in Potenza

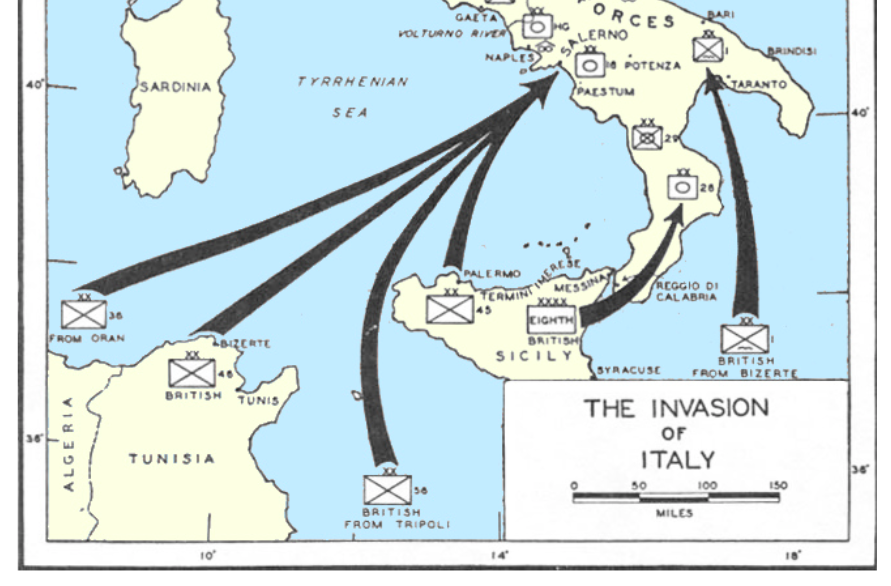

Then Hilda ‘she was initially interned and then paroled eventually living with nuns in a convent near Potenza’, a quiet city in Basilicata. Then, on 3 September 1943, the Allies invaded Southern Italy:

Ten days later the attack on Potenza began with heavy American bombing for a week [13th-19th]. Many refugees from Salerno and other civilians were killed and my mother helped nurse the wounded [also taking pity on terrified very young German soldiers in retreat]. She regarded the American bombing of cities, particularly ones declared ‘open’, there and elsewhere it Italy as an outrage.

The position of Potenza during the Allies invasion of Southern Italy.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Invasionofitaly1943.jpg

What happened next, following the final Allies victory in Europe [Spring 1945]?

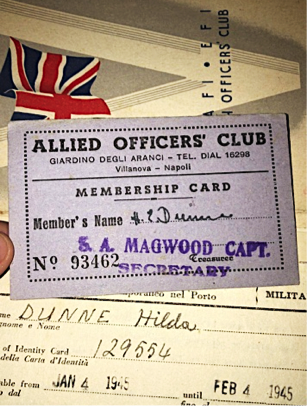

Nonetheless the allied victory led to her liberation after which she returned to Naples and worked for the Ministry of War Transport there [she helped in identifying former fascists, too]. One of her MOW civilian colleagues in Naples was the Irish novelist Brian Moore [I have some correspondence between them]. […] It was during this period that she met my father who was part of the allied liberation serving in the RAF. She would have continued with the work in the Ministry or perhaps have returned to theatre but she sought and was granted permission to return to the UK to be married in Whitstable, and then to move to Scotland where my father came from.

Hilda Dunne’s Allied Officers Club membership card (1945).

As John Haldane wrote:

it was located ‘on a hill overlooking Naples. It was described as a beautiful building, finished in marble, with an all-around balcony upstairs with an extra bar. The orchestra was Italian and excellent. Every imaginable uniform present—American, British, French officers, nurses, WAC’s, ATS, Red Cross girls, Canadians, Scotsmen dancing in kilts. Drinks were fairly good too’

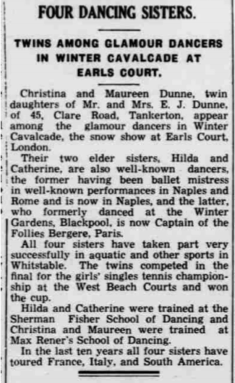

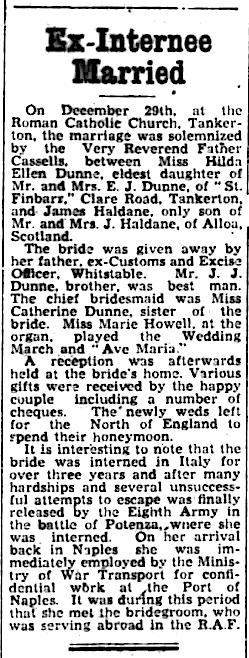

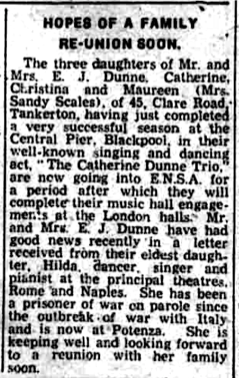

Below are some clippings about Dunne sisters’s story

-

Whitstable Times and Tankerton Press, 21st January, 1939,

courtesy of John Haldane

-

Whitstable Times and Tankerton Press, 11th September 1943

Courtesy of John Haldane

-

Whitstable Times and Tankerton Press, 19th January 1946

Courtesy of John Haldane

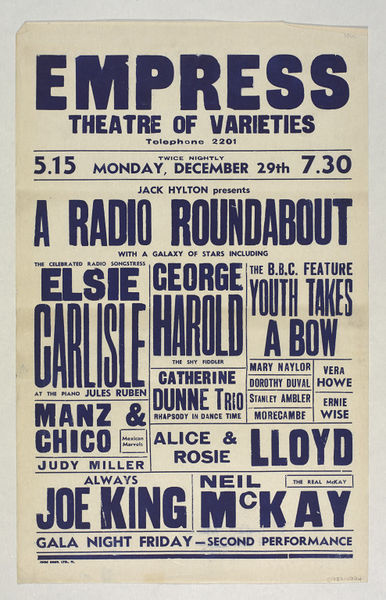

While Hilda was interned in Italy, the Catherine Dunne trio was still performing in London, as shown by this poster: December 1941

Source: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1162586/poster-unknown/

Turning back to the 1931 Naples match, there are no more sources regarding what subsequently happened. Reading a report published in March 1933 by La Voce Sportiva about the birth of Gruppo Femminile Calcistico in Milan, we could argue that some time after January 1931 Bebé Laviano was planning a further match, but was stopped by “Maestro” Giuseppe Zanetti, Vice-President of Federazione Italiana Giuoco Calcio (FIGC) with a sort of veto ‘ban’. Was Zanetti wanting to avoid the huge audiences that attended events such as the Naples match, which was not considered sports but a vaudeville show aping real football?

Anyway, at the end of 1931, the monthly magazine Lo Sport Fascista, which was a kind of official organ of the regime’s sports policy, published a picture of the match, telling the readers that ‘in Naples a match between a local sports club and 11 ‘girls’ from a theatre company that was there in Naples during those days. Of course, girls won this match, a bad taste show’. The conclusion being:

’If there’s a sport that women should not practice, this is precisely football!’

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, December 1931, p. 14

Article © Marco Giani

For more sources about 1931 Naples match, see: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1259041270066003968

For more sources about vaudeville women’s football in 1920s and 1930s Italy, see:https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1051215875389489153

![Playing Football with the Chorus Girls: <br>Vaudeville Women’s Football in Naples [1931]](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/PP-banner-maker.jpg)

![“And then we were Boycotted”<br>New Discoveries about the Birth of Women’s Football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 9](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Boycotted-part-9-Marco-440x264.jpg)