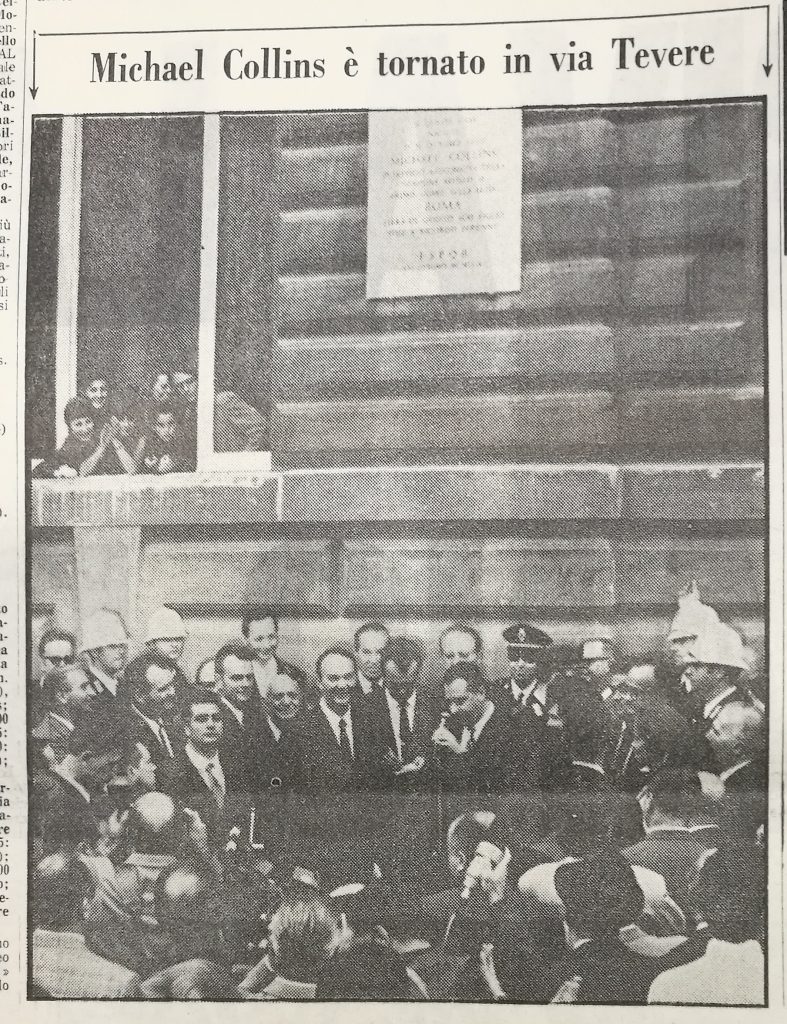

The newsreel “Radar” number 311 of October 1969, shown in cinemas across Italy rolls:-

Although this is the well-known building of the Italian Football Federation, here we are not talking about scoring goals. The building is less than a hundred meters from Via Tevere, a street in Rome that few people know and that would have remained anonymous if a long black car, escorted by motorcyclists and accompanied by his smiling wife, should not have landed one of the most famous men of our time, Michael Collins, one of the three legendary conquerors of the moon. Via Tevere has an important part in the biography of Collins, who was born on October 31st in the apartment from which a flag hung from the balcony today. In the stopover in Rome during the world tour, that he is making with his two colleagues, Collins came to Via Tevere to return to the haunts of his childhood, he discovered a tombstone that recalls the happy event, he listened to the Mayor of Rome, Darida, and received a plaque in memory of his Roman birthplace. Collins thanked with a moved voice and then jokingly asked to personally maintain the tombstone. Every month – he said – I wish I could come here, at the expense of the municipality of Rome, to dust the marble. Michael Collins left Via Tevere to applause and cheers from the whole neighbourhood.

-

The “Roman” astronaut is back home.

Il Messaggero, 17th October 1969.

That voice – one that certainly those of you born in Italy before the Olympics ’60 will remember – which commented on current events in cinemas during the interval – can easily be listened to today, with just a click of a computer mouse or a swipe of a finger across a mobile phone screen. But only half a century ago, such things were not conceivable or perhaps predictable, even though we were all pretty sure (I certainly was, as child with fantastic images in my head, thanks to the film 2001 A Space Odyssey) that lunar tourism would be made possible in 2019: “A ticket for the next moon-craft of 17 and 30, thanks, destination Crater Peary North Pole”.

By the 2000s we imagined we would have flying cars or travel through the streets of Rome via magnetic monorails, major cities of the world would have developed vertically, very similar to those of the Flash Gordon’s planet Mongo, a comic-strip that I was just becoming aware of at that time. It would, however, take another four or five years for me to discover the Urania Mondadori novels. In those feverish days of the “Apollo 11 mission, first man on the moon” – as chiselled on that plaque in Via Tevere – billions of words were written in Italy to emphasize the event, defined as a milestone in the history of humanity, humanity that is with a capital “H”. On the newscast, Carlo Fruttero and Franco Lucentini, science fiction experts and curators of the Urania series, were the only ones to venture to place a foot into that dark mud stain that sometimes is the Truth, stating tout court that it was just a question of “a nineteenth century business”, without too much gain in the future, apart from the experimentation of new technologies. Almost unanimously, the Western press predicted that, once man colonized the moon the earth would become a better place; that the Cold War would soon be over and man would have become wiser. And that the next exploration of outer space would be targeting Mars, the red planet, where perhaps man would meet the “Martians”, imagined as small creatures similar to luminescent amoebas.

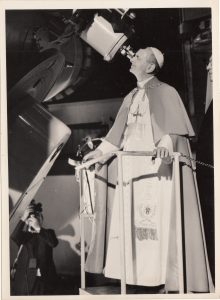

- The official photocard of the NASA and the coins created by New Yorker artist Ralph J. Menconi

In the United States of America, the nation that produced this crazy adventure, following the pointed forefinger of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, in the name of a healthy “sporting challenge” with the USSR, everyone of a certain age knew what they were doing at the exact moment the news of JFK’s murder was leaked out, also knew the answer to “on the moon!” – or where they were when that cry was launched by the people who witnessed the Apollo 11 mission lift-off. The same however, cannot be said for the moon landing here in Italy, followed on TV by millions of people from their living room armchairs or in countless public places, someone for 28 hours straight and almost all on the evening of 20 July 1969. It was more the funny misunderstanding between the very convulsed Tito Stagno, speaker of the first national channel, and the equally bitchy Ruggero Orlando, this time not the correspondent from “Nuova Iorche” but sent to Cape Canaveral, that occurred at the precise moment when the Eagle module touched down on the lunar surface, that remains in the memory of most. For my almost 9 year old self, I remember instead the transmission of two unmissable movies, The War of the Worlds and Destination Earth, and in the middle a car ride to the nearby Swiss-Sicilian pastry shop in Piazza Pio XI, where there towered, in a corner, a black and white “Telefunken” television set, we Italians didn’t experience the moon landing in full colour, as happened in America. With the exception that is, of a very special Italian, the Holy Father, who, thanks to the antenna of Radio Vaticana followed the original live commentary. He deserved it, on the moon the astronauts had carried a recording containing the greetings of the most powerful men on earth, including the Pope.

-

Paulus VI looking at the moon at the Astronomical Observatory of Castel Gandolfo, next to Rome.

This image was delivered to the press to confirm the approval of the Holy Father.

But who was Mike Collins? And why, as a newborn baby, had he seen the light of dawn burning off the crimson roofs and the travertine monuments of the Eternal City? His father worked as a military attaché at the US embassy which, incidentally, took up residence in Palazzo Margherita, the former Villa Ludovisi, in 1931. And so we are talking about Via Veneto, the future queen of the Dolce Vita, the street that American tourists in the summer of ’69 would have chosen to rejoice together with the stars and stripes flag firmly planted on the moon. The transfer to Via Veneto had caused the departure of James Lawton Collins from Rome, the first of many military bases in the first seventeen years of life of his son Mike.

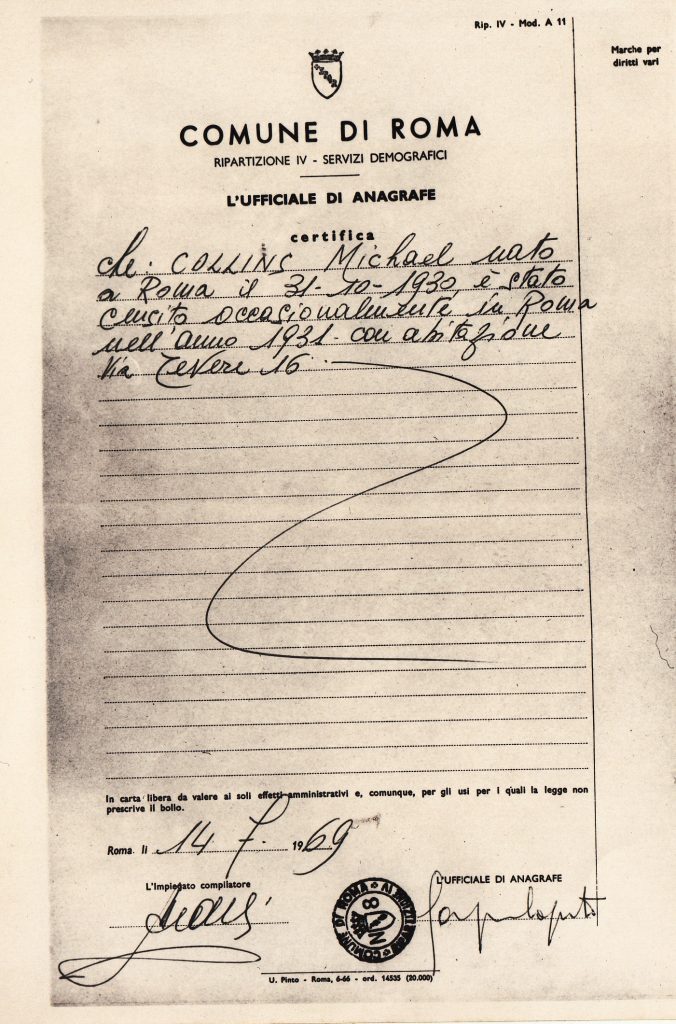

-

A document from the Municipality of Rome archives stating that Collins was born in the Eternal City in 1930

and counted in a census on 1931.

Mussolini ruled Italy, at that time.

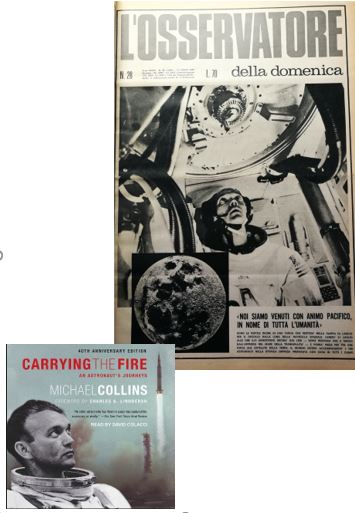

The boy graduated in biological sciences in Washington, attended the academy at West Point and in 1952 decided not to follow in the footsteps of his ancestors, all of them high-ranking in the army, but to become a “top gun” in the aeronautical forces. His autobiographical book Carrying the Fire, published in 1974, reveals that it was not until 1962 that Mike had the idea of being a astronaut. In 1966 he participated in the Gemini 10 mission, where he discovered a condition undoubtedly not suitable for space flights, claustrophobia. After the lunar landing, the NASA program proposed a reserve role in the Apollo 14 mission and command of the Challenger module in the Apollo 17 mission. With hindsight, we can say that Collins would have been the last man to leave his imprint on the lunar dust, however that fate, in December 1972, was actually the geologist Harrison Schmitt.

-

Command Module pilot Michael Collins at work.

The book he released in 1974, with a foreword by the aviator Charles Lindbergh.

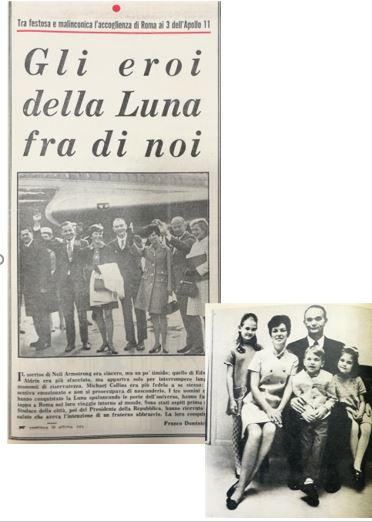

Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin and Collins, once they had endured the post-landing quarantine and enjoyed the traditional triumphal parade through the avenues of New York, from the Columbia spacecraft were placed almost seamlessly in Nixon’s presidential jet. It was a long tiring tour that, after Rome, included Belgrade and the Middle East on the way to the final destination of Tokyo. At Ciampino airport, the three astronauts arrived, accompanied by their wives, on the morning of October 15th.

-

Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins at the airport of Ciampino, on the morning of October 15th 1969.

Mike and his family: a good christian example of how to face life with serenity.

They stayed three days in Rome, meeting with many notable politicians, including the Undersecretary for Foreign Affairs Mario Pedini, in which Collins said My journey to the moon began in Rome and would not have been completed if I had not returned to my hometown. There followed a pleasant ride in the scorching sun in an open-top car along the Appian Way, a brief visit to the Archaeological Promenade and a reception held by Mayor Clelio Darida. Here Darida presented each of the ‘heroes’ with the classic Capitoline Shewolf statue in bronze. [The sculpture traditionally depicted a scene from the legend of the founding of Rome and shows a she-wolf suckling the mythical twin founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus]

- Capitoline Shewolf

A packed schedule for the three celestial globetrotters followed, with a press conference at the national broadcasting headquarters in Via Teulada, conducted by anchorman Sergio Zavoli in front of two hundred journalists, a meeting at the Quirinale with the President of the Republic, Giuseppe Saragat, a gala dinner at Castel Sant’Angelo hosted by the President of the Council, Mariano Rumor, and an audience with Paul VI on Thursday morning, with a second conference by the representatives of the episcopal synod.

-

Paulus VI in conversation with the astronauts during their visit to St. Peter’s headquarters in the State of Vatican,

16th October 1969.

- Neil Armstrong gives a souvenir to the President of the Italian Republic, Giuseppe Saragat.

Armstrong, above all, was the man in charge of describing the video of the “making of” of the Apollo 11 mission and of responding to reporters. He appeared quite fatigued in the lengthy discussions (repeated city after city…) and was always very serious, clearly worried about the political side of his office, especially when it came to facing the pro-American or pro-Soviet questions. While reading the contemporary newspapers it would seem as if it were really Collins, of the three, who was the most relaxed and amicable during these many exchanges. He who had not set foot on the moon, but had “only” guided the mother ship around the satellite before the recovery of the module, seemed the most open in showing his emotions publicly.

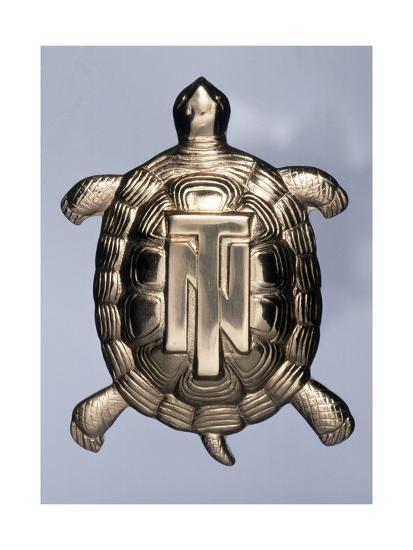

- Hop to the moon! Kathleen, Annie and Mike junior, children of the astronaut, smile at the launch of Apollo 11

He displayed an easy going manner, a kind of “Roman spirit” attitude, especially when speaking to the crowd gathered in front of the door number 16 Via Tevere. Recalling that there, right there, in the eight-room apartment on the fourth floor where a Yugoslavian family of an electronics company now lived, he had come into the world and tasted the first fruit jams, maybe an apple or a peach of the Sabina district. Indeed, given that he was there, with his wife Patty, he wanted to repeat certain lost experiences, relive lost memories. The couple, having gone up to the apartment and greeted Dr. Babic and his family and drank a small cup of Italian coffee, went to the terrace where Mike noticed on a square of earth, drinking from a basin of water, a green and brown tortoise, identical to the one he played with at the age of fifteen months. Quite a symbolic moment, because the tortoise is regarded as a creature of resilience and strength combined with tenacity and longevity. As a sports historian, I love the story of the gold tortoise-shaped brooch which was presented by the poet Gabriele D’Annunzio to racing driver Tazio Nuvolari – ‘The slowest animal to the fastest man on the earth’. The great “Nivola” was the winner of the 1931 Italian Grand Prix, the same time as little Michelino was playing on a terrace in Rome, destined to become the fastest extra-terrestrial Roman citizen.

-

Chelonian Tortoise

Donated by Gabriele D’Annunzio to Tazio Nuvolari in 1932,

This short essay, dedicated to Collins and to myself, who naively believed he could one day travel from earth to the moon in two hours, while at most in two hours I drive back from the seaside of Ostia on summer Sundays, could not be completed without the disclosure of a curious anecdote. Do you know that a souvenir of Rome almost ending up on the moon with Apollo 11, a coin, a Sestertium of the imperial age? The reporter Sergio Neri, who had been assigned the Apollo mission story for the magazine Corriere dello Sport was sent, in February 1969, to the deserts of Texas, where a dozen aspiring astronauts were preparing for lunar missions. He went to see Collins in his house on the outskirts of the centre of NASA, forty kilometres away from Houston, where Mike lived with his wife and three children. Mr. Neri had lunch with the family, spaghetti and meatballs in an American-style sauce, with crumbled grana cheese. Neri noticed a cheap print of the Colosseum hanging on a wall, and the fun with which Mike insisted on calling all Italians “paesano” [Paesano is defined as a fellow countryman, especially a fellow Italian]. Finally, before taking his leave, Mr. Neri pulled out of his jacket the Sestertium coin, bought in Rome by an antique dealer, with the effigy of the well-known She-wolf. Patty turned it over in her hands, amazed and happy at the unexpected gift. He thanked and passed the silver coin to her husband stating that that two-thousand-year-old manufact was much more important than all the stones he was going to collect with his friends “up there”. At that point, the Italian reporter found the courage to ask Collins if it would be possible to take the coin aboard the Columbia. Mike said that yes, it could be a nice souvenir for the trip, a lucky charm.

That old bit of Roman metal, of course, never went to the moon. But Mike, promised that he would come in person to Rome after the venture, and so it was. As the bard wrote: Men at some time are masters of their fates.

Article © Marco Impiglia [orginally published on Playing Pasts on 20th July 2019]

![“And Then We Were Boycotted” <br> New Discoveries About the Birth of Women’s Football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 3](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Marco-Giani-Boycotted-Part-3-440x264.jpg)