Previous parts of this series:

Part 1 – Cotton Lancashire’s Victorian Swimming Baths – can be read HERE

Part 2 – Public Baths Providing Health, Hygiene, and Exercise – can be read HERE

Part 3 – Collier Street Baths: Past, Present, Future – can be read HERE

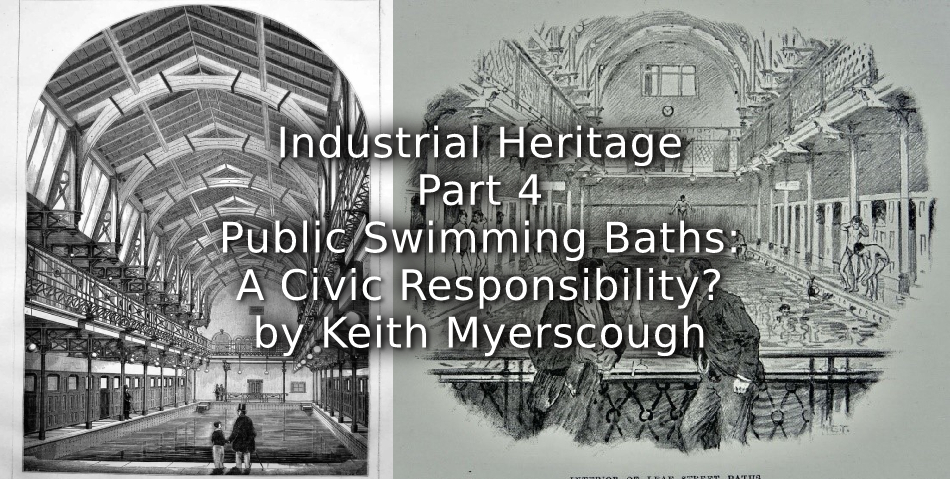

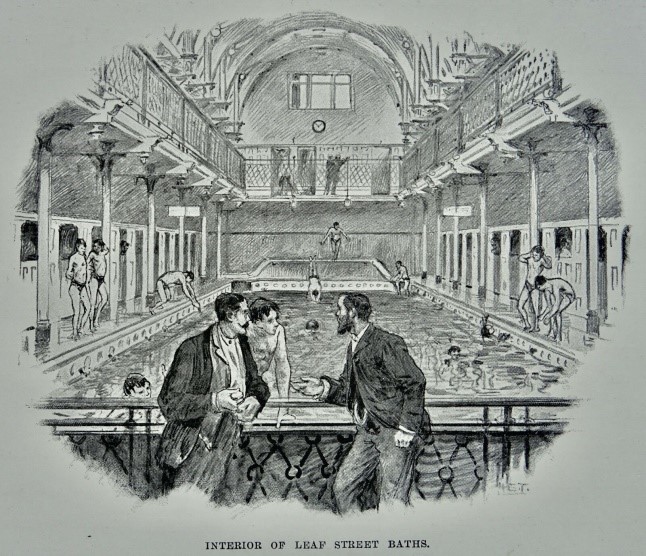

1st Class Baths at Leaf-Street, 1920

Source: Manchester Libraries Local History

The demand for bath-houses and wash-houses in Manchester and Salford was limited. The clarion call to improve the physical and moral condition of the nation’s working classes reflected political aspirations, stimulated by a desire to maintain the existing social class system. Many mill-towns in Lancashire had successfully implemented municipal public baths provision by means of benevolent exertion. Manchester and Salford elected to promote a public baths scheme, at no risk to the municipal purse, through private enterprise. Both means of provision co-existed in Lancashire until the late-1870s, with regional governance and laissez-faire economics driving social reforms. Lancashire’s mill-towns had adopted a more politically liberal ideology which was reflected in a greater willingness to adopt municipal public baths as a matter of civic responsibility. The era of municipal trading, more generally referred to as ‘municipal socialism’, greatly influenced baths provision post-1878.

A common denominator in the supply of public baths establishment’s was the provision of swimming facilities. In order to maximise profits, the Manchester and Salford Baths and Laundry Company embarked upon an extensive programme of presenting swimming as a sport, leisure activity, and recreational pursuit. The Mayfield and Leaf-Street Baths successfully developed strong swimming clubs who promoted the art of swimming by means of club galas, and swimming and life-saving lessons. Club members were amongst the elite amateur and professional swimmers in the country.

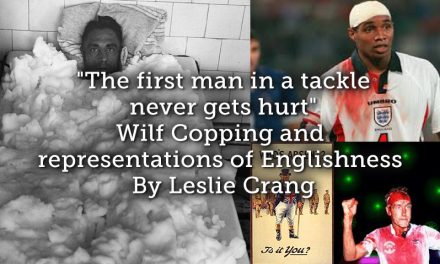

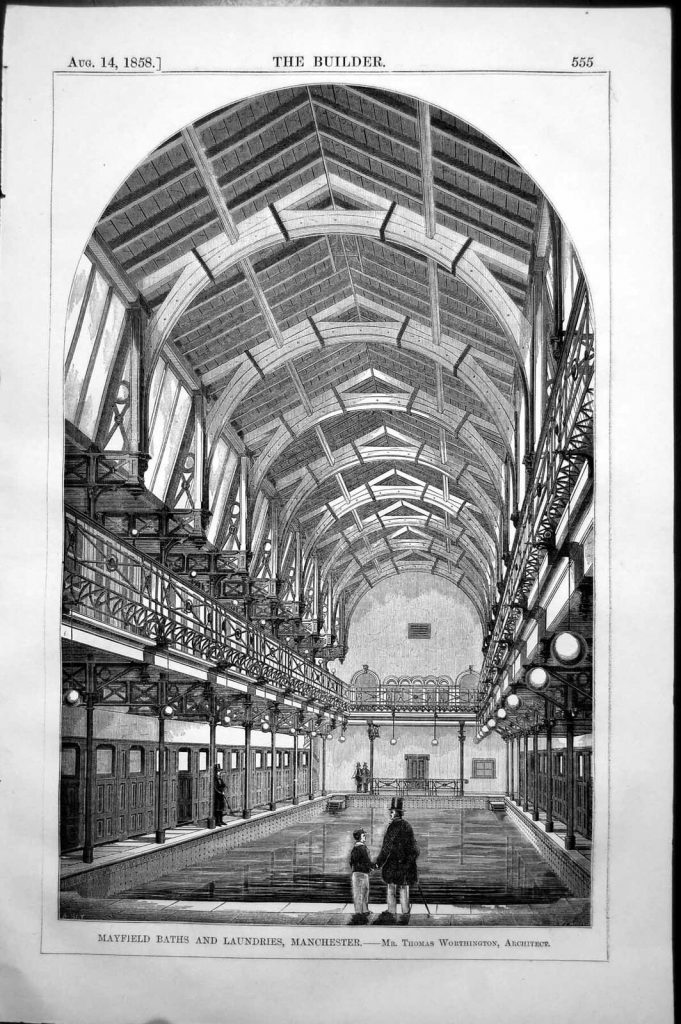

Mayfield Baths, 1912

Source: Manchester Libraries Local History

The Mayfield Baths had two bathing facilities; each with a swimming pool on the lower levels and a series of private baths on the upper level gallery. Despite declarations by the company that their first two establishments had been erected for the benefit of the ‘poorer classes’, the charges imposed did not reflect this. The charge for the first-class amenities was 6d, which included the supply of newspapers in the waiting room, and for the second-class facilities it was 2d. The poorest members of society were still without the means to wash their bodies and clothes in purpose-built accommodations.

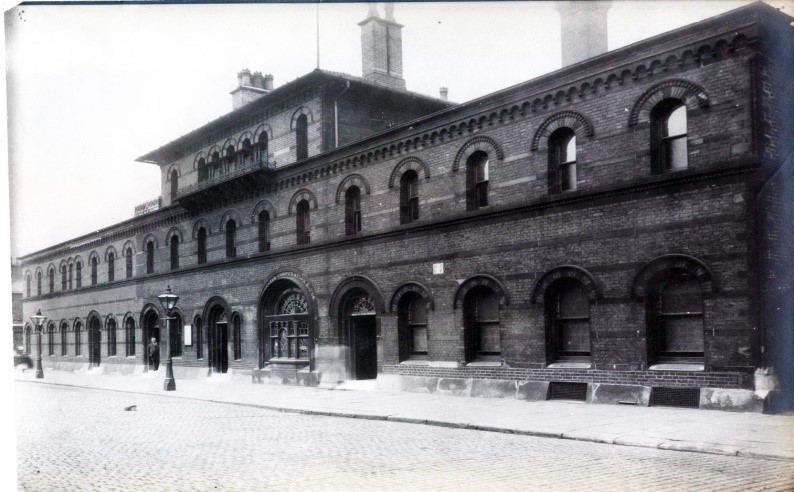

Leaf-Street Baths, c.1920

Source: Manchester Libraries Local History

Leaf-Street Baths was designed to cater for the new and aspiring middle classes of Manchester and Salford. It was the syndicate’s flagship; at a cost of nearly £12,000 it contained two large swimming baths, 75-feet by 25-feet, 44 private slipper baths, for men and women, a Turkish baths, and a public wash-house with 20 tubs. The establishment had three entrances in order to divide its customers by gender and the ability to pay. The charges mirrored those at the Mayfield Baths, creating the notion of exclusion and segregation. There was also an ‘extra first-class private baths’ that was furnished in a more expensive style which cost 1s per bather. The Leaf-Street Baths also had double baths for invalids.

In 1878 the Manchester and Salford Baths and Laundry Company was liquidated. They sold off the Mayfield and Leaf-Street Baths to Manchester Corporation, but Salford refused to purchase Collier-Street Baths as it would be too expensive to renovate. Manchester signalled its intentions by taking out a government loan of £50,000 for the purchase of the two baths and a plot of land in New Islington. Salford Corporation, in contrast, decided to embark upon its own building programme. By 1895, Salford had built four establishments: Blackfriars Road, Pendleton, Broughton, and Regent Road Baths – each one had two swimming pools. Between 1870 and 1906 Lancashire had 16 new-build public baths, each having at least two swimming pools.

The importance of wash-houses in public baths decline with the council’s slum clearance schemes and advances in water supplies to the housing stock. The traditional ‘Monday wash day’ was spent in the home rather than at the wash-house. There was also a marked decrease in the number of people making use of the private slipper baths. In 1904, Manchester Baths Committee recorded 255,825 swimmers and bathers at their Leaf-Street Baths, and 167,283 customers at the Mayfield Baths. Thus, the popularity of swimming facilities at municipal public baths was maintained with increased numbers of schoolchildren learning how to swim as part of the curriculum. The number of season tickets awarded to scholars for proficiency in life-saving during the 1905 season was 342, which had dropped from 582 in 1904. The total number of swimmers and bathers in Manchester’s municipal baths in 1905 was averaging 1.2 million visits per year; the income for 1904-1905 was £7,154. Contemporary attitudes towards baths provision in 1905 indicate the existence of new spheres of influence at the local government level. Community relationships and civic social responsibility had become prime political movers.

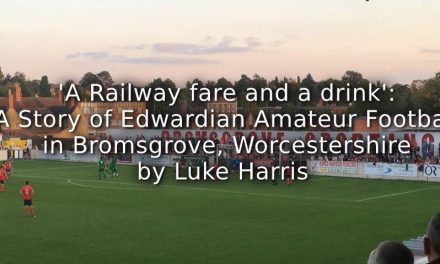

Leaf-Street Baths

Mayfield Baths

Source: The Builder, 14 August 1858 [both images]

Article © of Keith Myerscough